Over the past year, banks continued to experience deposit outflows. First, monetary policy actions increased short-term interest rates, which enticed many depositors to seek more profitable investment opportunities. Second, banking stress episodes led some large depositors to question the safety of bank deposits and seek alternatives. In response, banks raised deposit rates to retain their core funding. However, deposit rates have risen more slowly than yields on alternative investments.

Bank deposits are a foundational piece of the financial system, providing banks with low-cost funding and customers with convenient and safe liquidity. Bank deposits provide customers immediate access to funds and payment services, making them vital to many everyday transactions. Additionally, most household deposit accounts are fully insured against bank failure by the U.S. government, providing depositors peace of mind even in times of severe financial stress. As a result, many depositors may be reluctant to move their money out of deposits even when interest rates offered on alternative investments are higher than bank deposit rates.

However, some alternative investments, such as money market funds, may be close substitutes for deposits. Although money market funds do not offer the same payment services or loss guarantees as bank deposits, they do offer returns comparable to other short-term investments on funds that can be withdrawn at par value with limited risk. In addition, government money market funds pose virtually no credit risk because they are fully invested in assets issued or backed by the U.S. government. Many money market funds can also invest in the Federal Reserve’s Overnight Reverse Repurchase (ON RRP) facility, which provides participants short-term investments at an administered rate without imposing credit, interest rate, or counterparty risk.

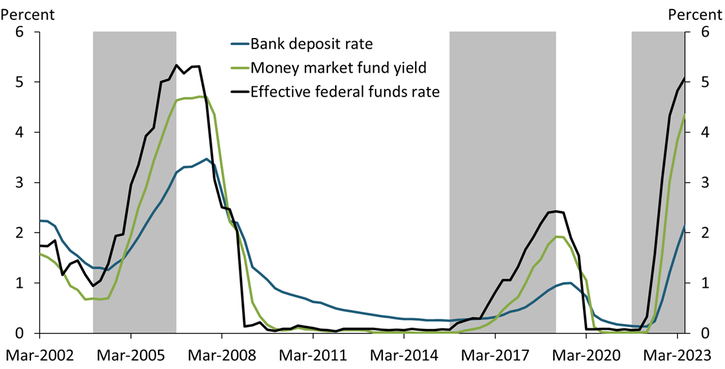

Historically, yields on money market fund investments have moved nearly concurrently with short-term policy rates, while deposit rates have lagged. Chart 1 shows the historical relationship between the effective federal funds rate, yields earned on money market fund investments, and average rates paid on bank deposits. During the two previous policy tightening cycles in 2004–06 and 2016–18, money market fund yields (green line) increased with only a slight lag relative to increases in the effective federal funds rate (black line). Bank deposit rates (blue line), on the other hand, increased more slowly during each tightening cycle. These differences in both the size and pace of increases for bank deposit rates and money market fund yields led to sizable spreads between the two, which tended to remain until the effective federal funds rate began to decline. The current tightening cycle’s dynamics mirror those of past cycles. Money market fund yields have quickly accelerated, while bank deposit rates have lagged, resulting in a current spread of more than 2 percentage points.

Chart 1: Increases in money market fund yields have significantly outpaced bank deposit rates

Notes: Money market fund yield is the annualized quarterly return. Bank deposit rate is interest paid on deposits to average interest-bearing deposit balances. Shaded areas denote periods of rising policy rates.

Sources: Federal Financial Institutions Examinations Council, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, and iMoneyNet.

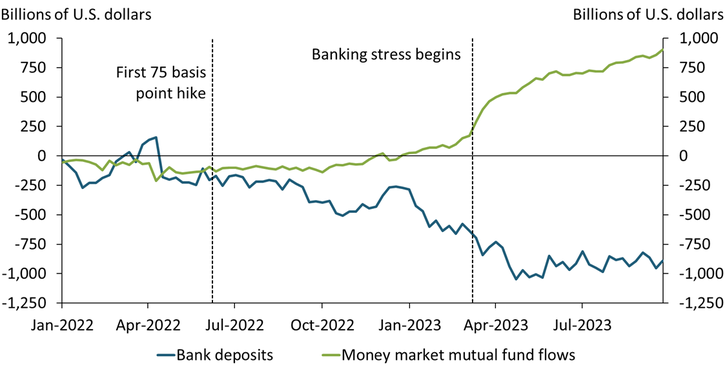

Bank deposit accounts offer customers greater convenience than money market funds and are accordingly expected to have lower rates; however, the current spread is about double the peaks in past tightening cycles. Partly as a result, money market fund assets have grown, while deposits have declined. Chart 2 shows that from 2022:Q1 through 2023:Q3, money market funds (green line) experienced cumulative inflows of about $900 billion. Those inflows are almost exactly matched by the total amount of bank deposit outflows (blue line) during that time._ Notably, both money market inflows and deposit outflows accelerated in March 2023, when high-profile bank failures led uninsured depositors to question the safety of their deposits. Government money market funds, in particular, benefitted from uninsured depositor flight (not shown).

Chart 2: Nearly a trillion dollars have flowed from bank deposits to money market funds

Note: Chart shows cumulative money market mutual fund inflows and cumulative bank deposit outflows since the start of 2022.

Sources: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System and U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

Both future monetary policy actions and developments in the banking system could narrow this spread, albeit through different channels. If monetary policy eases and the federal funds rate declines, money market fund yields could fall faster than bank deposit rates as some deposit types reprice slowly (Laliberte, Marsh, and Sharma 2023). Moreover, while both deposit rates and money market fund yields tend to decline with the effective federal funds rate, deposit rates tend to remain above money market fund yields following the end of easing cycles (see Chart 1). Depositor preferences and product composition are both likely contributors to this dynamic. Specifically, deposit products that impose withdrawal restrictions, minimum balances, or have long maturities, such as certificates of deposit, must compensate depositors with higher rates than those offered on less restrictive account types._

If policy rates remain elevated, the current spread between money market fund yields and deposit rates is still likely to narrow as bank deposit rates “catch up.” Deposit rates are unlikely to have fully adjusted to current policy rate levels, as increases in deposit rates typically lag increases in the federal funds rate for some time (Driscoll and Judson 2013; Dreschler, Savov, and Schnabl 2017, 2021). Moreover, Greenwald, Schulhofer-Wohl, and Younger (2023) show that bank deposit rates tend to rise sluggishly at the start of a hiking cycle before rising more rapidly later. Average rates paid on deposits were still climbing as of 2023:Q4 and may climb further if policy rates remain elevated.

Although the factors driving deposit rates and money market fund yields in these policy scenarios differ, bank deposit levels are likely to remain stable in both cases. Indeed, deposit outflows largely stabilized in the second half of 2023 as deposit rate increases have continued._ Moreover, deposits remaining at banks are more likely to be held by depositors who value the convenience and safety of bank deposits over higher yields offered by alternative investments.

Endnotes

-

1

Depositors also have other short-term investment opportunities available such as Treasury bills. Indeed, both banks and money market funds experienced outflows for much of 2022 as interest rates began to increase.

-

2

Interest-bearing deposit growth tends to slow as rates fall because the opportunity cost of holding lower-yielding deposits declines. Noninterest-bearing deposits are currently 23 percent of total deposits compared with 30 percent in 2021:Q4.

-

3

Current cumulative deposit runoff levels are in line with early predictions of how deposit outflows would respond to rising money market fund yields. Morgan and others (2022) predicted deposit migration to money market funds would total about $600 billion through 2024.

References

Dreschler, Itamar, Alexi Savov, and Phillip Schnabl. 2021. “External LinkBanking on Deposits: Maturity Transformation without Interest Rate Risk.” Journal of Finance, vol. 76, no. 3, pp. 1091–1143.

———. 2017. “External LinkThe Deposits Channel of Monetary Policy.” Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 132, no. 4, pp. 1819–1876.

Driscoll, John C., and Ruth A. Judson. 2013. “External LinkSticky Deposit Rates.” Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, FEDS working paper no. 2013-08, November.

Greenwald, Emily, Sam Schulhofer-Wohl, and Joshua Younger. 2023. “External LinkDeposit Convexity, Monetary Policy, and Financial Stability.” Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas, working paper no. 2315, October.

Laliberte, Brendan, W. Blake Marsh, and Padma Sharma. 2023. “Community Bank Funding Is Getting Costlier and Riskier.” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Economic Bulletin, December 18.

Morgan, Luke, Anthony Sarver, Manjola Tase, and Andrei Zlate. 2022. “External LinkBank Deposit Flows to Money Market Funds and ON RRP Usage during Monetary Tightening.” Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, FEDS working paper no. 2022-060, July.

W. Blake Marsh is a senior economist and Padma Sharma is an economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City. Chris Acker is a research associate at the bank. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City or the Federal Reserve System.