Oklahoma’s economy grew solidly for much of the first half of 2019. In recent months, however, several broad economic indicators have shown weaker readings, as a sizable downturn in the state’s important energy sector appears to be affecting economic growth in the state overall. This edition of the Oklahoma Economist examines how the state’s economy has evolved in 2019, and where it stands heading into 2020.

Job growth and tax revenues have slowed

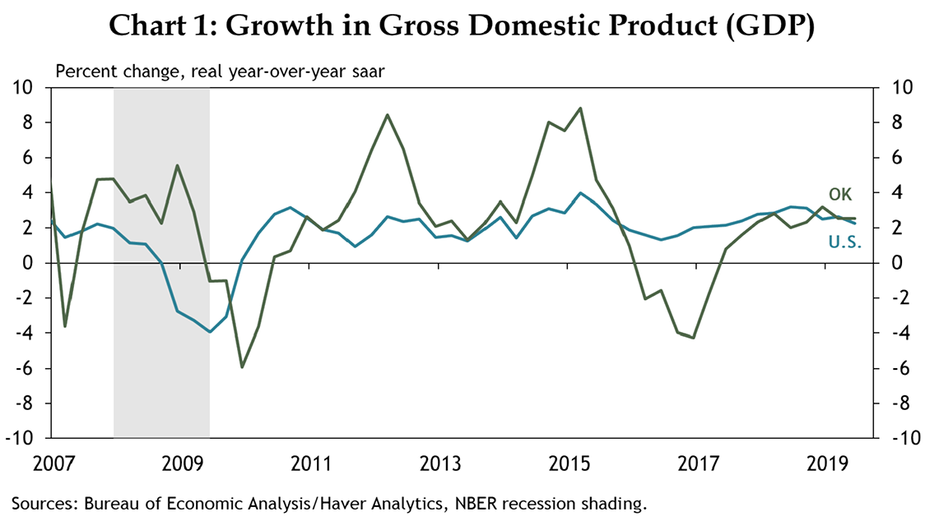

Real gross domestic product (GDP) in Oklahoma continued to expand at a rate similar to the rest of the nation in the first half of 2019 (Chart 1). However, several more timely indicators of broad economic activity at the state level now show very little if any growth in the state’s economy as of the fourth quarter.

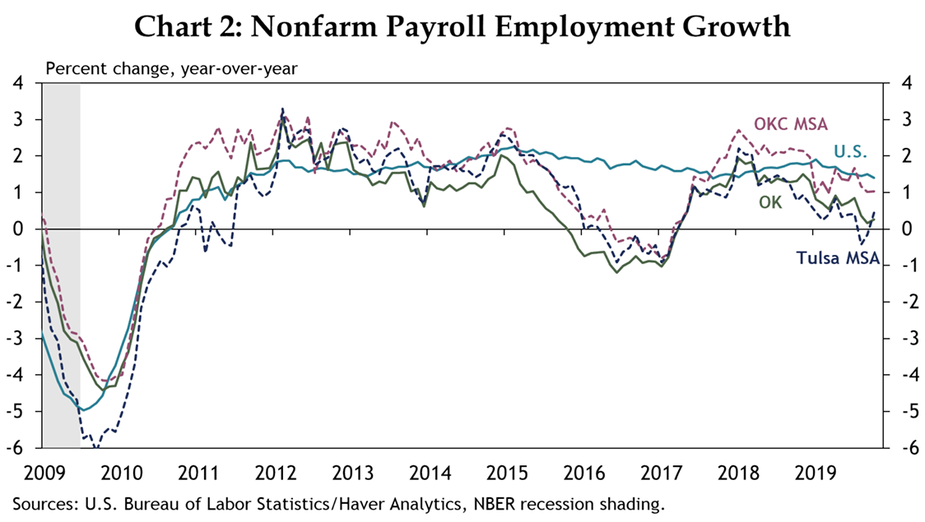

The pace of Oklahoma’s nonfarm job growth has slowed steadily in 2019, and employment in the state now is up only slightly from a year ago (Chart 2). The slowdown in job growth also has been evident in the state’s two large metro areas, although job growth in both Oklahoma City and Tulsa as of October was slightly higher than the state average.

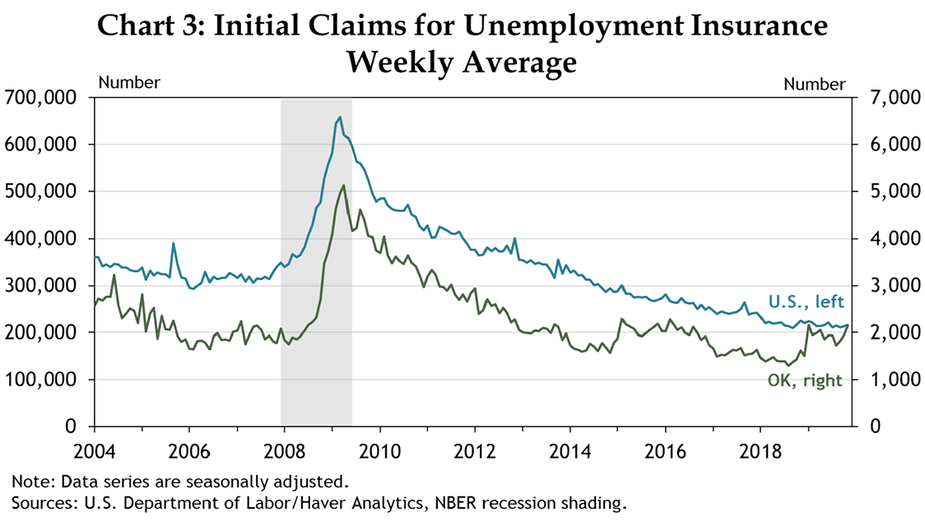

Amid slower job growth, the state has seen an elevated level of new claims for unemployment insurance (Chart 3). For much of the year, new claims have been running near their 2015-16 levels—when the state was in a recession. The most recent data available, for November, show an additional increase in claims.

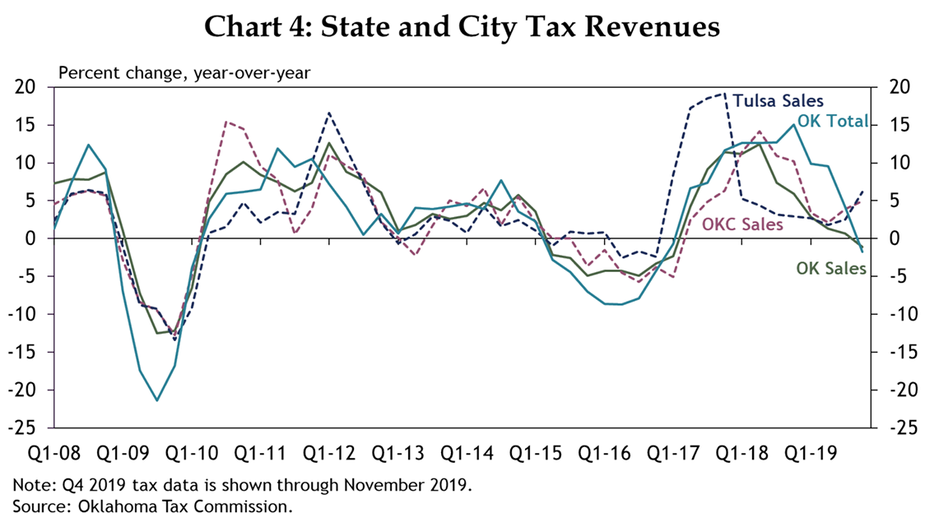

Tax revenues in Oklahoma also have slowed in 2019 (Chart 4). By early in the fourth quarter, both total and sales tax revenues in the state had dropped below year-ago levels for the first time in nearly three years. Sales tax receipts in the two largest cities also have slowed this year. However, both cities have seen a modest uptick early in the fourth quarter, keeping revenues above year-ago levels.

Slowdown in energy spreads to other sectors?

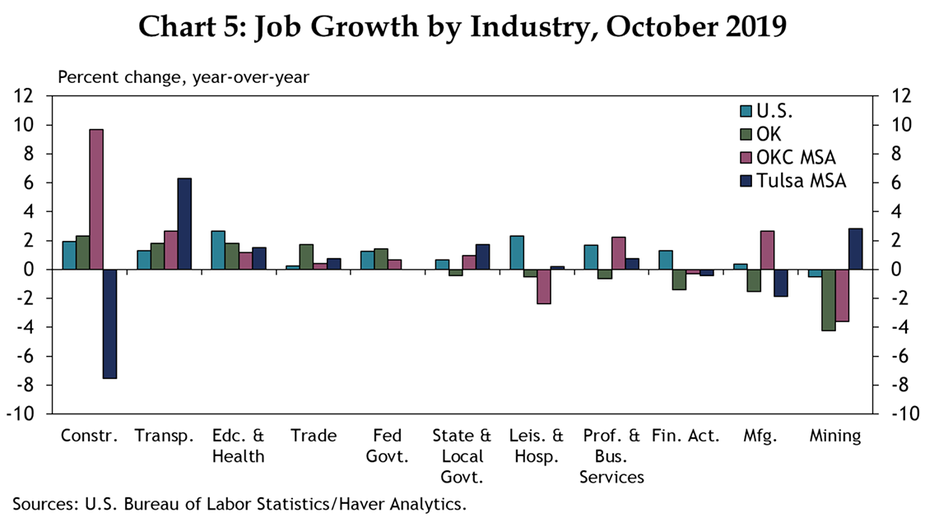

Looking across industries, the biggest drop in activity this year has been in the state’s important energy sector. Employment in mining, which in Oklahoma consists almost completely of oil and gas, was down more than 4 percent from a year ago as of October, over twice as much as in any other sector (Chart 5).

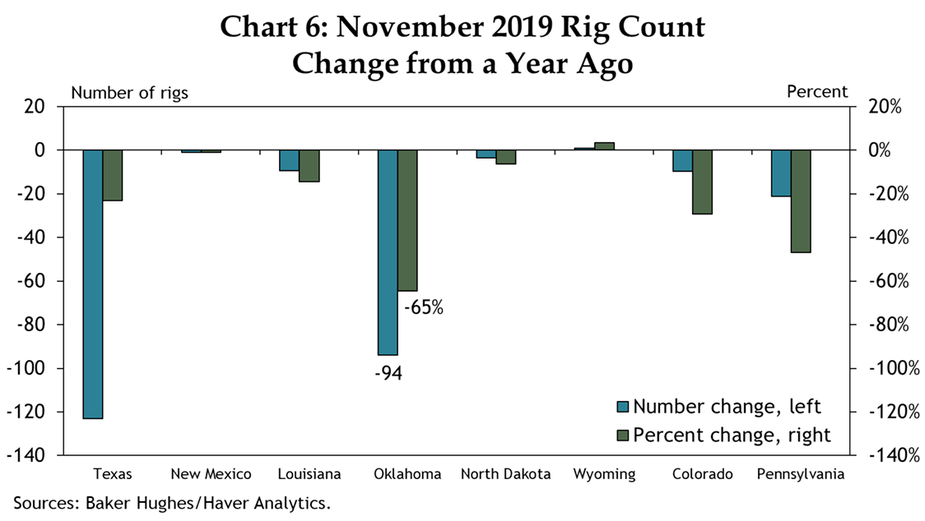

Oil prices have remained near the price that firms in the Kansas City Fed’s quarterly External LinkEnergy Survey said is needed to be profitable—$55/barrel—for most of the year, but natural gas prices generally have remained well below their profitable level of just under $3.00/mbtu. Firms also have produced more oil and gas in recent years with fewer rigs and workers, as explained in the External LinkOklahoma Economist from the second quarter of 2018. In addition, Oklahoma’s rig count has dropped much more than any of the other top eight oil- and gas-producing states, a result of some firms moving assets to other oil- and gas-producing areas (Chart 6).

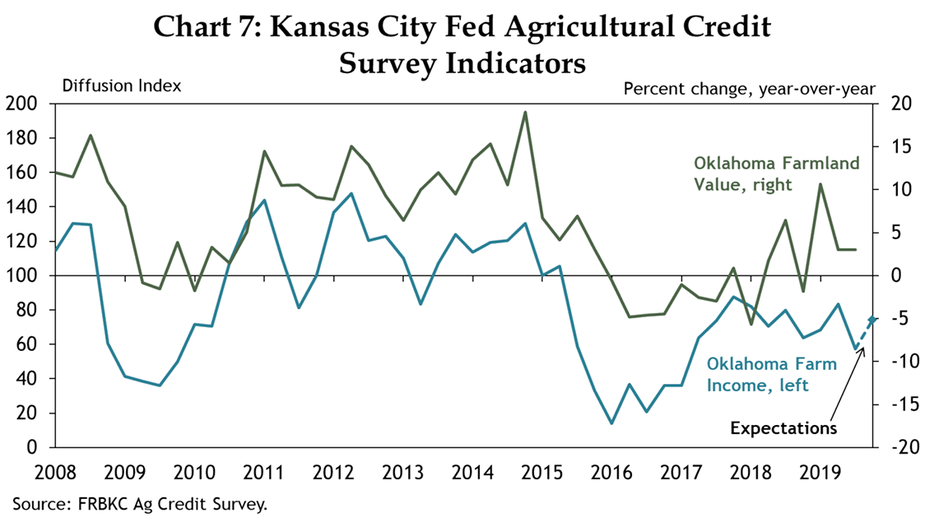

At the same time, conditions in the state’s agriculture industry—vitally important to many parts of the state—also have remained difficult. Farm incomes have continued to decline, although at a slower pace than in recent years (Chart 7). More positively, farmland values generally have held up despite some volatility in recent years, providing some support to farm finances.

Other sectors of the state’s economy appear to be experiencing the effects of challenging environments in energy and agriculture. Employment in manufacturing has dropped this year, likely affected by trade uncertainty and weaker demand from the energy and agricultural sectors. Jobs in the state’s financial, business services, leisure and hospitality, and state and local government sectors also have fallen slightly.

Outlook for 2020

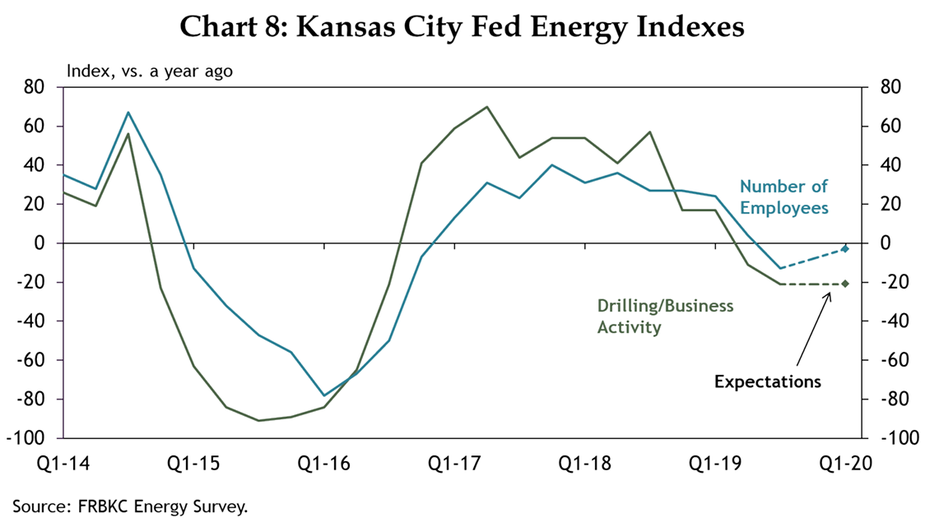

Given the large decline in Oklahoma energy activity in 2019, the outlook for that sector remains key for understanding where the state stands heading into 2020. According to the latest Kansas City Fed External LinkEnergy Survey, conducted in late September, firms on net indicated they anticipate additional deterioration in drilling activity over the next six months (Chart 8). They also indicated they expect slight additional reductions in oil and gas jobs, but by less than in the recent past.

More positively, several other sectors of the state’s economy have continued to grow through late 2019, as shown in Chart 5. These include construction, transportation, health care, trade and federal government. In addition, several other sectors in the two largest metros also continue to add jobs at a modest pace, including in professional and business services in both Oklahoma City and Tulsa, as well as manufacturing in Oklahoma City and mining in Tulsa. Continued strength in these sectors would bode well for the state’s economy in 2020.

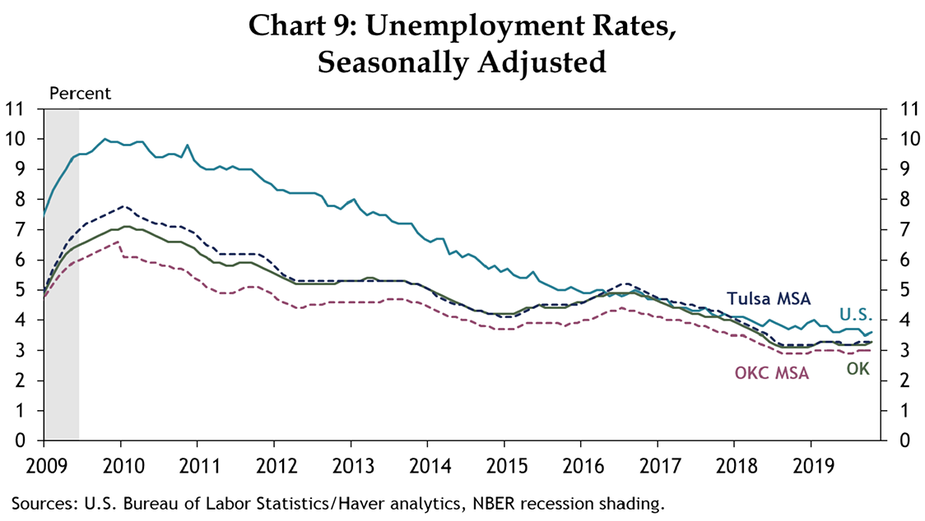

Finally, despite the slowdown in the state’s economy this year, unemployment remains exceptionally low. Joblessness in the state overall and in both large metros remains below the national average, which itself is at a 50-year low (Chart 9). As such, employees who lose jobs in one sector of the state’s economy may benefit from a still-tight labor market and find jobs in other sectors.

Summary

Although Oklahoma’s economy continued to expand through the first half of 2019, several indicators of economic growth have slowed more recently. In recent months, job growth has stalled, unemployment claims have risen and tax receipts have declined, suggesting little, if any, overall growth in the broad state economy. Energy activity in particular has declined significantly this year, and expectations among energy firms remain somewhat downbeat for early 2020. Still, employment is up in several key sectors, and unemployment in the state remains very low, which could help Oklahoma weather current economic difficulties.