Sharp increases in interest rates have led to higher interest expenses in the agricultural sector, with interest rates on farm loans nearly tripling from the beginning of 2022 to the end of 2023. In fact, in 2023, interest expenses represented the fastest growing source of total farm production expenses (Giri and Subedi 2023). While higher interest expenses have particularly affected newly purchased or refinanced assets such as farmland (see Kreitman 2023), interest expenses have also increased dramatically for producers along the beef supply chain. Interest expenses for cattle producers have been intensified by higher interest rates, higher prices for cattle to restock herds, and increases in other production expenses. Together, higher prices and borrowing costs could squeeze profit margins for cattle producers and contribute to a prolonged period of lower cattle supply.

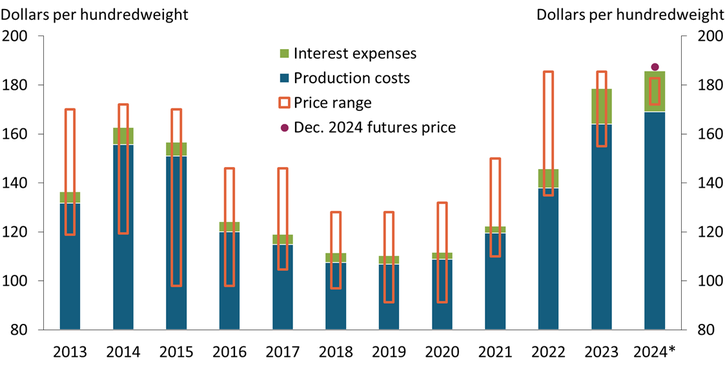

Although increases in cattle prices largely offset higher interest expenses in 2022 and 2023, profit margins have tightened recently. Chart 1 shows that over most of the last decade, the annual range of prices producers received for cattle (orange boxes) was above average costs of production (blue and green bars). In other words, cattle producers had opportunities for positive profit margins nearly every year. However, so far in 2024, the range of prices has stayed below the total cost of production. Although interest expenses (green bars) make up a small share of total production costs, growth in interest expenses when margins are tight can be the difference between positive and negative profit margins. For stockers and feedlots, profit margins have turned negative in the early months of 2024; while margins may not yet be negative for cow-calf producers, higher prices and borrowing rates have also made purchasing new stock more difficult. Futures markets suggest that prices could increase further this year, but so far, higher interest expenses have challenged profitability for the average cow-calf operation.

Chart 1: So far in 2024, cattle prices have remained strong but have not kept pace with growth in interest and other expenses

Notes: Bar for 2024 represents staff estimates as of February 2024. Production costs are based on estimates from USDA High Plains Cattle Feeding Simulator, and price ranges are live cattle prices reported by the Wall Street Journal.

Sources: U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), Wall Street Journal (Haver), Iowa State University, and CME Group.

One reason cattle prices have remained strong is low inventories. Total inventories for cattle and calves have declined since 2019 amid supply chain disruptions related to the global pandemic and widespread, severe drought. In January 2024, cattle inventories reached their lowest levels in more than 70 years, and recent developments suggest U.S. cattle herd numbers could decline even further. The number of cattle sold to feedlots, or cattle on feed, rebounded, which means more cattle continue to be sold off farms and into the beef supply chain. Also, inventories for beef cows and heifers continued to decline, signaling that market and financial conditions have been more conducive to selling heifers and cows than retaining them. And in March 2024, U.S. cattle production suffered additional losses due to wildfires in Texas and Oklahoma, where it is estimated that thousands of cattle have perished alongside other tremendous damages.

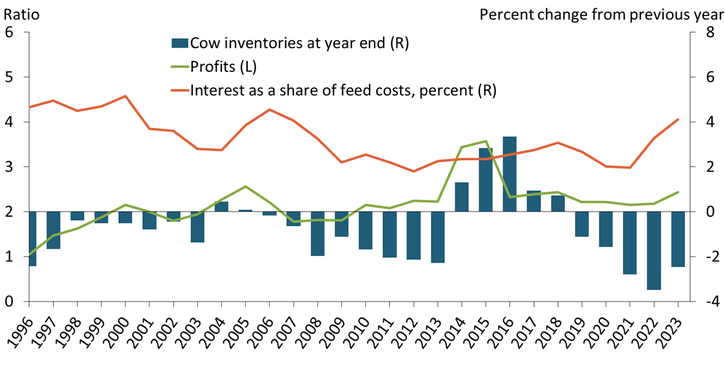

Lower feed costs have historically helped offset declining inventories. Feed makes up a large majority of total production expenses for cattle, especially feeder cattle, and lower feed costs have been a major incentive for producers to rebuild herds in past years. Chart 2 demonstrates that profits (green line), or the ratio of calf selling prices to the cost of feed, increased in 2023 as feed costs moderated. According to Cowley (2021), cattle inventories typically increase in the year after producer profitability (that is, the price-to-feed-cost ratio) increases and decrease the year after profitability declines. However, the blue bars in Chart 2 show that despite stable profitability from 2019 to 2022, cattle inventories continued to decline, likely due largely to the pandemic and drought. Moreover, despite an increase in profitability in 2023, inventories were still lower at year-end. Higher interest rates (orange line) accounted for some of the increase in costs of purchasing additional animals and could prevent inventories from rebuilding momentum.

Chart 2: Cattle inventories tend to follow measures of profitability

Note: Measure of interest as a share of feed costs assumes producers finance 50 percent of feed costs at the average interest rate for each year.

Sources: USDA and authors’ calculations.

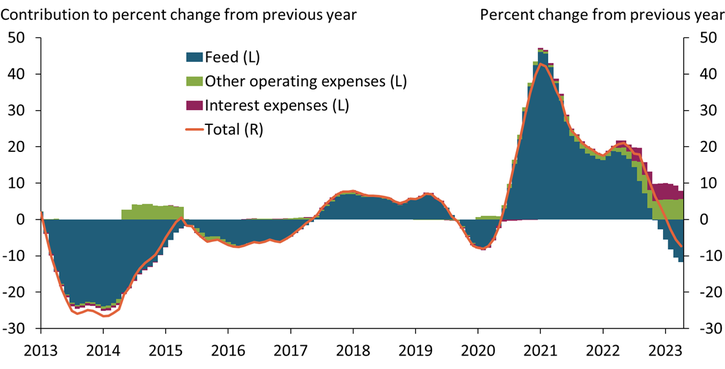

Moreover, declines in feed costs have recently been offset by increases in interest and other operating expenses. Chart 3 shows that unlike in previous cycles, interest expenses (maroon shading) increased notably in 2023, and other operating expenses, such as labor, transportation, and utilities, also grew at a stronger-than-normal pace (green shading). Although total production costs for a feeder calf purchased in the middle of the year fell about 7 percent in 2023 (orange line), driven exclusively by lower feed costs (blue line), higher interest and other operating expenses made up the difference. Moving forward, operating profits will likely need to increase considerably to incentivize robust herd expansion. The path of operating profits will be most heavily influenced by feed costs, other operational costs, and interest expenses.

Chart 3: Recently, lower feed costs have been offset by higher interest and other operating expenses

Sources: Iowa State University, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, and authors’ calculations.

In conclusion, higher interest expenses are challenging farm profitability in the cattle industry, especially for producers that rely heavily on financing for cattle and other production expenses. Interest expenses are a small share of overall production expenses and have been offset in recent years by higher prices for cattle. However, as profit margins have tightened, higher interest expenses have constrained profit opportunities for producers. As in any business, expansion in cattle production tends to rely heavily on profitability; when a producer’s ability to expand is restricted, so are their opportunities for future returns. A prolonged period of restricted supplies and high prices could reduce demand in domestic and international beef markets, especially because options for other proteins are plentiful and prices for other meats such as chicken and pork have declined.

Download Materials

References

Cowley, Cortney. 2021. “External LinkLong-Term Pressures and Prospects in the U.S. Meat Supply Chain.” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Economic Review, vol. 107, no. 1, pp. 23–43.

Giri, Anil K., and Dipak Subedi. 2023. “External LinkIncreases in U.S. Farm Debt and Interest Expenses Minimally Affect Sector’s Financial Position in the Short-Term, as Measured by Liquidity and Solvency Ratios.” U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service, Amber Waves, August 10.

Kreitman, Ty. 2024. “External LinkInterest Expenses on Farmland Debt Could Challenge Farm Profitability.” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Economic Bulletin, February 14.

Cortney Cowley is a senior economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City. Ty Kreitman is an associate economist, and Francisco Scott is an economist at the bank. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City or the Federal Reserve System.