Efforts to achieve digital payments inclusion—meaning all consumers can access safe and affordable digital payment products or services to meet their transaction needs—have often focused on increasing bank account ownership. According to the 2021 Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households (hereafter, the FDIC survey), 4.5 percent of U.S. households are unbanked and could be considered excluded from digital payments.

However, focusing on bank account ownership may understate digital payments inclusion, as some households may use nonbank transaction accounts to make and receive digital payments relatively safely and affordably. In this briefing, I examine the extent to which nonbank transaction accounts help promote digital payments inclusion among unbanked households. I find that around 40 percent of unbanked households may have used nonbank transaction accounts to access digital payments in 2021. I then discuss strategies to promote digital payments inclusion among households that do not use nonbank transaction accounts.

Nonbank transaction accounts as an alternative to bank accounts

Bank account ownership has traditionally been the primary way households access digital payments through instruments such as debit cards and fund transfers via the automated clearinghouse (ACH) system or the Zelle network. Over the past few decades, however, nonbank transaction accounts such as prepaid cards and nonbank payment accounts have also emerged (Greene and Shy 2023). Many providers of nonbank transaction accounts offer a similar suite of transaction products and services to those offered by banks. These products and services are often more affordable and safer compared with nonbank paper-based transaction products and services.

One older version of these products is a general-purpose reloadable (GPR) prepaid card, which households can purchase at many major retailers or online. Before households can use their GPR card for the first time, they need to load funds onto the card through either a bank transfer, direct deposit, or cash deposit at select retailers (including large national chains such as CVS, Dollar General, and 7-Eleven). Once loaded with funds, households can use their GPR card to pay bills, make purchases in person and online, and withdraw cash at an ATM, just as with a bank debit card. Households can also receive payments, such as direct deposits of paychecks and government benefits, and send money to friends and family domestically from their GPR prepaid card account, as with a bank account. The cost to use a GPR prepaid card varies depending on the fees the card provider imposes and how the cardholder uses the card. Hayashi and Cuddy (2014) estimate the average monthly cost to use a GPR prepaid card to be around $15 to $17, but this cost may be lower for GPR cards that offer cardholders options for free cash reloads and ATM withdrawals._ GPR prepaid cardholders who register their cards benefit from similar consumer protection to bank account and debit card holders. For example, the funds on most prepaid cards are FDIC-insured, conditional on registration (National Consumer Law Center 2019). Registered GPR prepaid cardholders also benefit from fraud protection and error resolution under the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s Regulation E (which protects consumers when they transfer funds electronically). Moreover, card networks such as Visa, Mastercard, and American Express offer their prepaid cardholders the same fraud protection as their credit and debit cardholders.

A newer form of nonbank transaction accounts are digital transaction accounts offered by nonbank financial technology (fintech) firms, such as online payment service providers._ A key distinction between these accounts and GPR prepaid card accounts lies in their technological requirements: smartphone or internet access is not necessary for GPR prepaid cards but is required to use nonbank digital transaction accounts. That distinction aside, nonbank digital transaction accounts are increasingly like GPR prepaid cards in their features and functionalities. In addition to online payment services, major online payment service providers such as PayPal and Cash App now offer consumers the ability to receive direct deposits and deposit cash and even paper checks into their accounts. They have also penetrated point-of-sale (POS) payments; PayPal and Cash App account holders can obtain debit cards linked to their accounts to make POS payments or even pay directly using mobile apps at many retailers. Like GPR prepaid cards, the cost to use these digital transaction accounts varies by account provider and how households use these accounts. Although the monthly average cost to use these accounts is unknown, accounts with major providers such as PayPal and Cash App appear to come with fewer fees than GPR prepaid cards._ In addition, many providers of digital transaction accounts hold customer deposits in accounts at partner banks, and their account holders may benefit from passthrough FDIC insurance._ Regulation E also applies to these transaction accounts, offering some fraud protection to consumers.

Although the nonbank transaction accounts described above provide many of the same services as bank accounts, they are not perfect substitutes. Providers of nonbank transaction accounts do not have physical branches that households can access for in-person services or assistance, and many do not provide checking or check-cashing services. Unlike banks, these accounts also often charge fees for cash deposits.

However, some characteristics of nonbank transaction accounts may make them more accessible or appealing than bank accounts for unbanked households. For instance, nonbank transaction accounts typically do not have minimum deposit requirements, which are a barrier to bank account ownership for many unbanked households. Further, many providers of nonbank transaction accounts offer their account holders early access to incoming payments, such as payroll and government benefits, which may make transaction account ownership more attractive to unbanked households who may otherwise use check-cashing services. To the extent that nonbank transaction accounts provide a more accessible or appealing alternative for unbanked households, they can help increase digital payment inclusion among these households.

Adoption of nonbank transaction accounts among unbanked households

One way to assess the effectiveness of nonbank transaction accounts in facilitating digital inclusion is to assess the adoption rate of these accounts among unbanked households. According to the 2021 FDIC survey, 32.9 percent of unbanked households used prepaid cards to conduct transactions, while 18.1 percent used accounts with online payment service providers. Overall, 40.7 percent of unbanked households used at least one of these two types of nonbank transaction accounts (with some households using both). As the FDIC survey also included nonbank transaction accounts that are limited in their functionalities compared with bank accounts—for instance, electronic benefit transfer prepaid cards—this estimate provides an upper bound for the share of unbanked households that I consider to be included in digital payments._

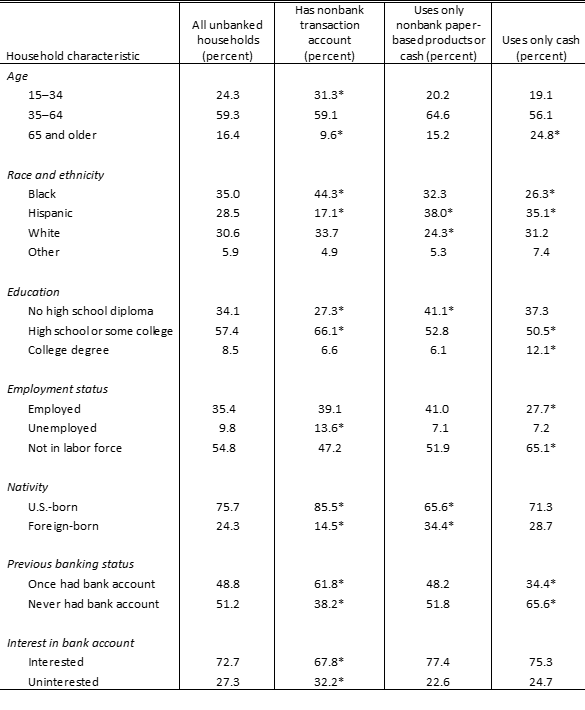

Nonbank transaction accounts appear to be a more effective solution to digital payment inclusion for certain types of households. Table 1 shows that unbanked households that use nonbank transaction accounts are significantly more likely than the average unbanked household to be younger than age 35, Black, unemployed, U.S.-born, to have a high school diploma or some college education, to have had a bank account in the past, and to be interested in having a bank account. In contrast, unbanked households that do not use nonbank transaction accounts are significantly more likely to be 65 years or older, Hispanic, foreign-born, to have no high school diploma, and to not have had a bank account in the past—implying that nonbank transaction accounts may not be as accessible or appealing to these households. Unbanked households that do not use nonbank transaction accounts either use costly paper-based transaction products or services such as nonbank money orders, check cashing, and money transfers (23.2 percent of all unbanked households) or cash only (36.0 percent of all unbanked households) to conduct transactions. Some of the unbanked households that are less likely to use nonbank transaction accounts (specifically, those that are Hispanic, foreign-born, or that have no high school diploma) are significantly more likely to use costly paper-based transaction products and services and may benefit from lower transaction costs by adopting nonbank transaction accounts (Toh 2021b). Other households that are less likely to use nonbank transaction accounts (specifically, those 65 years and older, Hispanic, and that have never had a bank account) are significantly more likely to be fully cash based. Although these households may also benefit from lower transaction costs by adopting nonbank transaction accounts, they may be less interested in doing so.

Table 1: Household characteristics of nonbank transaction account users and nonusers

Notes: Asterisks indicate that the proportion is significantly different from the proportion in the overall unbanked population at a 5 percent level. Unbanked households that are interested in having a bank account include those that are very interested and somewhat interested in opening a bank account. Unbanked households that are uninterested in a bank account include those that are not very interested and not at all interested in opening a bank account.

Sources: FDIC and author’s calculations.

How nonbank transaction accounts have (and haven’t) helped with digital payments inclusion

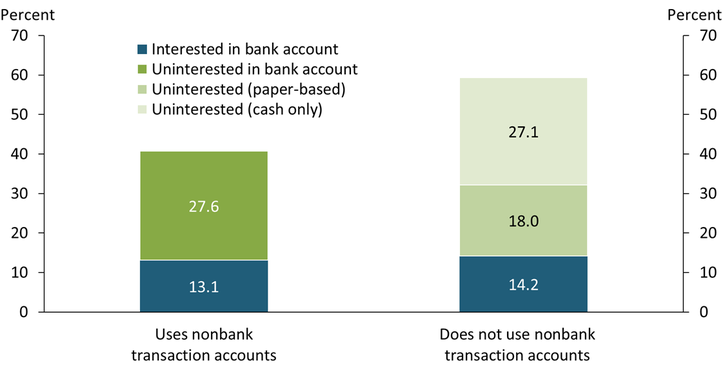

Nonbank transaction accounts appear to have helped promote digital payments inclusion among unbanked households by being both more accessible and more appealing to some unbanked households. Chart 1 shows that around one-third of unbanked households that used nonbank transaction accounts (13.1 percent of all unbanked households) were somewhat or very interested in opening a bank account. These users of nonbank transaction accounts were likely unbanked mainly because they faced barriers to obtaining a bank account, implying that nonbank transaction accounts have been more accessible to these households than bank accounts. The remaining users of nonbank transaction accounts (27.6 percent of all unbanked households) had little to no interest in opening a bank account. That these households adopted nonbank transaction accounts suggests that they found nonbank transaction accounts to be more appealing than bank accounts. Access to nonbank transaction accounts may be an especially important solution to digital payments inclusion for the latter group of nonbank transaction account users, as policies to promote bank account ownership are likely to be ineffective among these households.

Chart 1: Nonbank transaction accounts are more accessible and appealing to some unbanked households

Sources: FDIC and author’s calculations.

Although nonbank transaction accounts provide a path to digital payments inclusion for some unbanked households, they are unlikely to be an adequate solution on their own. As Chart 1 illustrates, the majority of unbanked households do not use nonbank transaction accounts. Among these unbanked households, only a small share (14.2 percent) indicated they may be interested in nonbank transaction accounts. The remaining 45.1 percent of unbanked households have neither adopted nonbank transaction accounts nor are interested in having a bank account (uninterested nonusers), implying that they also may not be interested in nonbank transaction accounts. Notably, most of the uninterested nonusers (27.1 percent of all unbanked households) are fully cash based. Fully cash-based nonusers who are uninterested in opening a bank account are arguably the least interested in nonbank transaction accounts and have the least need for them, as they are able to meet all their transaction needs using only cash.

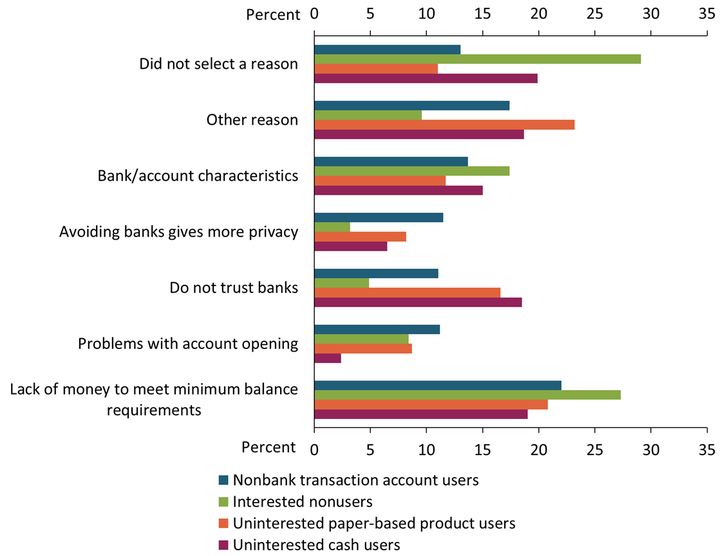

Understanding where nonbank transaction accounts fall short in accessibility or appeal is especially important as it can help inform strategies for digital payments inclusion. To help answer this question, I examine the main reason for being unbanked reported by four groups of unbanked households: (1) nonbank transaction account users, (2) nonusers who are interested in having a bank account (interested nonusers), (3) nonusers who are uninterested in having a bank account and use nonbank paper-based products (uninterested paper-based product users), and (4) nonusers who are uninterested in having a bank account and use cash only (uninterested cash users). The main reasons that nonbank transaction account users cite are those that nonbank transaction accounts may be better able to address, whereas the main reasons that nonusers are more likely to cite may be those that nonbank transaction accounts are less able to address.

The FDIC survey provides respondents with a list of possible main reasons for being unbanked; some reasons are related to the accessibility of bank accounts (that is, the household’s ability to open and maintain an account), while others are related to the appeal of bank accounts. Reasons concerning the accessibility of bank accounts include minimum balance requirements and problems with opening an account (due to a lack of proper identification or poor banking history); reasons concerning the appeal of bank accounts include a lack of trust in banks, privacy concerns, and undesirable bank or account characteristics (for example, inconvenient bank locations, high or unpredictable fees, or a mismatch between bank products and households’ needs).

Chart 2 shows that users of nonbank transaction accounts are more likely than all groups of nonusers to cite privacy concerns and problems with opening an account as their main reasons for being unbanked, suggesting that nonbank transaction accounts may address these barriers to bank account ownership. Unbanked households appear less likely to experience difficulties opening a nonbank transaction account than a bank account, possibly because providers of nonbank transaction accounts do not review consumers’ past banking histories when deciding whether to approve their account applications. Users of nonbank transaction accounts also seem to perceive nonbank transaction accounts as less privacy-intrusive than bank accounts.

Chart 2: Unbanked households cite different main reasons for being unbanked

Sources: FDIC and author’s calculations.

Main reasons for being unbanked differ across the three groups of nonusers, especially between interested and uninterested nonusers. Chart 2 shows that interested nonusers (in green) were more likely than all other groups of unbanked households to cite a lack of money to meet minimum balance requirements and unappealing bank or bank account characteristics as their main reason for being unbanked, whereas uninterested nonusers, especially uninterested cash users (maroon), were more likely to cite a lack of trust in banks. Uninterested, paper-based product users (orange) were also more likely to have provided other reasons as their main reason for being unbanked, whereas interested nonusers and uninterested cash users were less likely to have provided any reason.

The higher tendency for interested nonusers to cite a lack of money to meet minimum balance requirements and unappealing bank or bank account characteristics suggest that nonbank transaction accounts may not be more accessible or appealing to interested nonusers. That the lack of money to meet minimum balance requirements appears to pose a barrier to accessing nonbank transaction accounts is notable, as nonbank transaction accounts typically do not impose minimum balance requirements. This finding suggests that these households may simply lack money to keep in an account—a barrier that may require broader economic policies beyond the scope of digital payments inclusion to fully address. Efforts to promote digital payments inclusion among interested nonusers may need to focus on better understanding what these households need or desire in transaction accounts and products and designing transaction products that are accessible and appealing to them. Conducting qualitative research to understand why these households do not adopt transaction accounts may also be critical to informing digital payments inclusion strategies, as close to 30 percent of these households did not provide any reason for being unbanked.

Uninterested nonusers’ higher tendency to cite a lack of trust in banks as their main reason for being unbanked suggest that they are likely to lack trust in financial institutions more broadly. Building uninterested nonusers’ trust in banking and financial institutions may be a critical first step to promoting digital payments inclusion among these households. More qualitative research to understand why these households do not adopt nonbank transaction accounts may also be necessary—uninterested nonbank paper-based product users were more likely to have cited other reasons than the ones listed as their main reason for being unbanked, while uninterested cash users were more likely not to have provided any reason.

Promoting digital payments inclusion among uninterested nonusers is likely to be challenging, especially among uninterested cash users. As Chart 2 shows, uninterested cash users appear more likely to be unbanked by choice—they may be less likely to face barriers to accessing bank accounts, such as problems with opening accounts. Moreover, about 20 percent of uninterested cash users did not provide any reason for being unbanked, which may indicate that they do not face any barrier to bank account ownership, though more research is needed to verify this.

Conclusion

Nonbank transaction accounts may help promote digital payments inclusion among some unbanked households by serving as a more accessible or appealing alternative to bank accounts. About 40 percent of unbanked households used these accounts in 2021. However, they do not appear to adequately address the barriers to transaction account ownership for most unbanked households. More qualitative research is necessary to better understand the specific barriers to transaction account ownership faced by these households. Efforts to build unbanked households’ trust in financial institutions may also be critical to promoting payments inclusion among nonusers of nonbank transaction accounts who are uninterested in bank account ownership.

Finally, promoting payments inclusion among unbanked households may reduce their transaction costs only to the extent that their payment counterparties adopt digital payments. Over half (52.8 percent) of unbanked households who used nonbank transaction accounts also used paper-based transaction products and services, suggesting that unbanked households’ payment counterparties (for example, landlords) may be more likely to use paper-based payment methods. Unbanked households are substantially more likely to be renters, and many landlords only accept checks or money orders for rent payment._ Many unbanked households may also continue to be paid by checks, which they may not be able to deposit into their nonbank transaction accounts, resulting in their use of nonbank check-cashing services. Promoting the adoption of digital payments among unbanked households’ transaction counterparties may thus help lower payment transactions costs incurred by unbanked households.

Endnotes

-

1

Both the Walmart MoneyCard and the Bluebird American Express prepaid card provide their cardholders with free cash reload and ATM withdrawal options, which may substantially reduce the cost to use these GPR prepaid cards.

-

2

Another type of nonbank digital account is a neobank account. Neobanks are fintech firms that offer digital banking services to consumers through partnerships with chartered banks. Neobanks are characterized by their strong mobile and online banking platforms and often offer novel services such as early access to incoming payments, interest-free cash advances, and savings and investment tools in addition to traditional banking services (Bradford 2020). I do not include neobank accounts in the discussion as the distinction between neobank accounts and bank accounts may not be evident to most households, and many neobank account holders may consider themselves banked.

-

3

For instance, neither PayPal nor Cash App charge monthly maintenance fees, whereas many GPR prepaid card providers do.

-

4

Households may need to complete additional steps to benefit from passthrough FDIC insurance coverage on funds in their transaction accounts with nonbank online payment service providers (Consumer Financial Protection Bureau 2023). For example, PayPal Balance account holders can benefit from passthrough FDIC insurance if they open a PayPal debit card account or enroll in direct deposits, and Cash App Balance account holders can benefit if they link their account to a Cash App prepaid card.

-

5

Consumers are typically not able to reload cash onto government benefit cards. Further, some government benefit cards such as those for the Supplementary Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) and the Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) program are limited-purpose cards that recipients can only use to make certain types of purchases. See Toh (2021a) for a discussion of the different types of prepaid cards.

-

6

According to JPMorgan, about 78 percent of landlords receive rent payments via paper checks or money orders (Son 2022).

References

Bradford, Terri. 2020. “External LinkNeobanks: Banks by Any Other Name?” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Payments System Research Briefing, August 12.

Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. 2023. “External LinkAnalysis of Deposit Insurance Coverage on Funds Stored through Payment Apps.” Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, Issue Spotlight, June 1.

Greene, Claire, and Oz Shy. 2023. “External LinkHow US Consumers without Bank Accounts Make Payments.” Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, Policy Hub, no. 1-2023, January.

Hayashi, Fumiko, and Emily Cuddy. 2014. “External LinkGeneral Purpose Reloadable Prepaid Cards: Penetration, Use, Fees, and Fraud Risks.” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Research Working Paper no. 14-01, February.

National Consumer Law Center. 2019. “External LinkNew Protections for Prepaid Accounts.” Press release, March 28.

Son, Hugh. 2022. “External LinkJPMorgan Chase Wants to Disrupt the Rent Check with Its Payments Platform for Landlords and Tenants.” CNBC, October 31.

Toh, Ying Lei. 2021a. “External LinkPrepaid Cards: An Inadequate Solution for Digital Payments Inclusion.” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Economic Review, vol. 106, no. 4.

———. 2021b. “External LinkWhen Paying Bills, Low-Income Consumers Incur Higher Costs.” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Payments System Research Briefing, November 23.

Ying Lei Toh is an economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City or the Federal Reserve System.