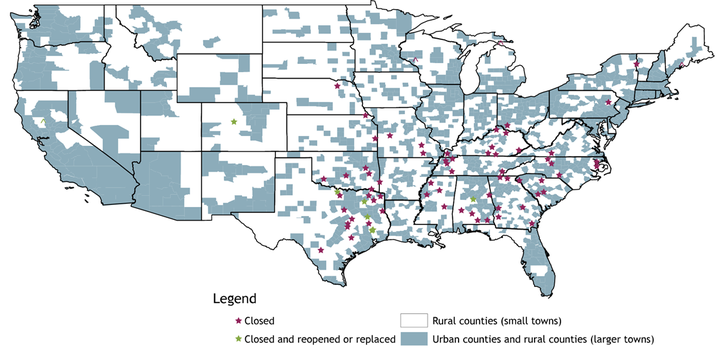

Since 2011, 74 hospitals have closed in rural counties isolated from larger towns—specifically, counties that do not have any towns with more than 10,000 people._ Map 1 shows that these closures have been highly concentrated in the Southeast, particularly in east Texas and southeast Oklahoma. According to the American Hospital Association (2019), many factors contribute to hospital closures; in the end, however, hospitals close because they are not financially viable. Indeed, both Oklahoma and Texas were among the six states with the highest concentration of rural hospitals in the “at-risk pool” in a recent study of hospital finances by Morgan Stanley (Ellison 2018). Hundreds of existing rural hospitals are at high risk of eventual closure if their financial conditions do not improve. A 2019 study by Mosley and DeBehnke suggests 21 percent of all currently operating rural hospitals are at risk of closure.

Map 1: Hospital Closures in Rural Counties Isolated from Larger Towns, 2011–19

Notes: “Rural counties (small towns)” are counties that do not have any towns with a population of 10,000 or more. These make up my study area. All other counties are “urban counties and rural counties (larger towns).” All reopened hospitals are considered closed in the analysis if they were closed for three years or more before reopening. Although a hospital in Cleveland, TX, is listed as reopened on the map, I consider it a closure in my analysis given that the Texas Organization of Rural & Community Hospitals lists the reopened hospital as an emergency room with only two acute-care beds. East Texas Medical Center: Crockett closed in 2017 and is therefore not included in the analysis. The hospital reopened in 2018.

Sources: InfoGroup, the American Hospital Directory, D&B Hoovers, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), and author’s calculations.

Despite heightened community concerns about recent hospital closures in rural areas, few researchers have analyzed the economic outcomes associated with these closures. One exception is a commonly cited study by Holmes and others (2006), which examines rural hospital closures from 1990 to 2000. The authors find that the closure of the sole hospital in a county is associated with a 4 percent decline in per-capita income and a 1.6 percentage point increase in the unemployment rate._

I analyze more recent rural hospital closures and evaluate changes in employment and wage growth in the affected counties after the closure._ Specifically, I compare growth in employment and aggregate wages in counties with hospital closures to growth in employment and aggregate wages in counties without hospital closures three years before and after closure._To ensure job and payroll losses directly associated with a hospital closure are incorporated in the analysis, I use the year prior to the closure as the reference year for the calculations. Thus, for a hospital that closed in 2013, I measure growth in employment and aggregate wages in the county in which it closed from 2009 to 2012 and from 2012 to 2015. Because annual employment and wage data are available only through 2018, I limit the analysis to hospitals that closed from 2011 to 2016.

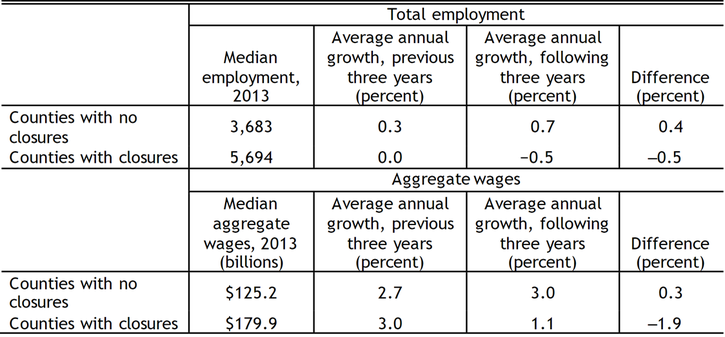

The results in Table 1 demonstrate that rural counties with hospital closures saw meaningfully lower annual growth in employment and aggregate wages three years after the closure than counties without hospital closures. Specifically, employment in counties with hospital closures fell at an annual rate of 0.5 percent in the three years following the closure, while aggregate wages grew at a moderate annual rate of 1.1 percent. Over the same period, counties without hospital closures had positive average annual employment growth of 0.7 percent and higher annual aggregate wage growth of 3.0 percent._

Table 1: Economic Effect of Hospital Closings in Rural Areas (2011–16)

Sources: Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) and author’s calculations.

Comparing post-closure economic performance to pre-closure economic performance adds further support to these results. Employment growth in counties that eventually lost hospitals was flat three years before the closure; over the same period, employment grew at an average annual rate of 0.3 percent in counties that did not go on to lose hospitals. Employment growth declined in counties that lost hospitals three years after the closure; over the same period, employment growth accelerated in counties without hospital closures. The growth rate in these counties increased by 0.4 percentage point.

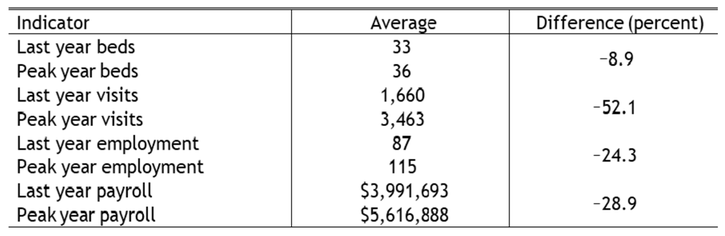

The results in Table 1 may understate the effects of hospital closures, as hospital employment, payroll, and other performance metrics—such as the number of inpatient visits and acute-care beds—declined for some time in most hospitals before formal closure. To highlight these declines, Table 2 compares hospital performance metrics in the closure year to its peak year after 2010. On average, hospital employment in the closure year (for all 74 hospitals) was 24.3 percent below its post-2010 peak. Similarly, hospital payroll was almost 29 percent lower in the closure year than its post-2010 peak. The number of acute-care beds declined only modestly, but inpatient visits declined by 52 percent.

Table 2: Decline in Rural Hospitals that Closed (2011–19)

Notes: Averages are for the 67 hospital closings in the study area for which full annual CMS cost report data are available. Only Medicare and Medicaid visits are available in the CMS cost reports. I assume that, on average, these visits proxy for total inpatient visits. Although some states expanded Medicaid during the study period, expansions likely increased visits, so my results are more likely to underestimate the decline in total visits than overestimate it.

Sources: CMS and author’s calculations.

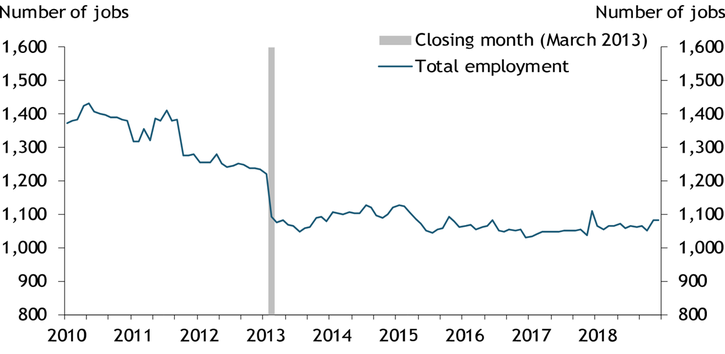

Although Tables 1 and 2 show results for the average county in the study area that lost a hospital, economic outcomes could vary dramatically across individual counties. Hospital closings have a much larger effect on smaller counties—such as Calhoun County, GA—that have a higher share of hospital employment and payroll relative to total county employment and wages. Chart 1 shows that the employment effects of the March 2013 closing of Calhoun Memorial Hospital were obvious and dramatic: the hospital closure put 94 people out of work in a county with total employment of 1,249 (7.5 percent). Employment in Calhoun County still has not recovered. In the three years following the hospital closure, average annual employment growth was ‒4.4 percent, due mostly to the initial drop in employment.

Chart 1: Effects of the Calhoun Memorial Hospital Closure on County Employment

Note: Data are seasonally adjusted using the U.S. Census Bureau’s X-13ARIMA-SEATS methodology.

Source: BLS.

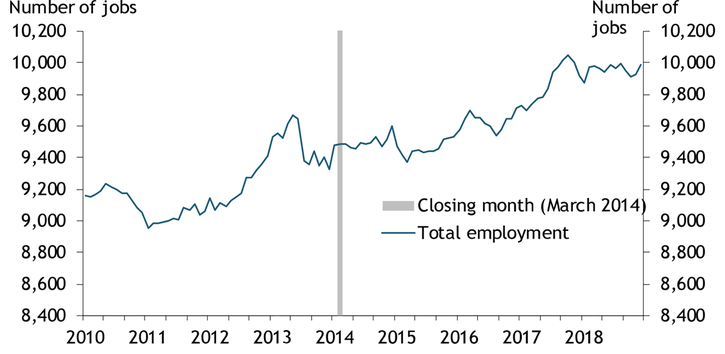

Hospital closures may have minimal effects on employment in other counties. Chart 2 shows the employment effects of the March 2014 closing of Lake Whitney Medical Center in Hill County, TX. The hospital closure put 67 people out of work in a county with total employment of 9,484 (0.7 percent). While the chart shows a slight initial decline in employment after the closure, total employment recovered quickly, growing at an average annual rate of 0.7 percent in the three years following closure.

Chart 2: Effects of the Lake Whitney Medical Center Closure on County Employment

Note: Data are seasonally adjusted using the U.S. Census Bureau’s X-13ARIMA-SEATS methodology.

Source: BLS.

Overall, my analysis shows that rural hospital closures are associated with sizable declines in county employment and aggregate wages. The declines are likely to be more severe in counties with lower total employment and a higher share of hospital employment and payroll. Many other counties remain at risk of especially severe economic consequences if their hospitals close. In my study area, 203 of the 1,200 counties with open hospitals have total employment below 2,000.

Longer-term repercussions of hospital closures could further impede economic growth in counties with closures. Loss of access to care is arguably the most fundamental concern for communities facing hospital closures. The effects of access to care on community health are well-documented—see, for example, Gulliford and others (2002)—and poorer health may lead to economic consequences such as increased worker absences and lower productivity. In addition, access to quality health care is an important amenity—especially in rural areas—that households and businesses may consider in choosing where to locate.

Endnotes

-

1

Using the definition of “rural” followed by the Federal Office of Rural Health Policy, which is quite broad, would add another 43 facilities to my post-2010 list of rural hospital closings, bringing the total to 117. However, some of these hospital closings are in cities of 25,000 or more, for which the economic repercussions would likely be different from cities in my study area.

-

2

The authors do not use comparison counties in the analysis but instead consider the economic performance of counties that will eventually experience a closure but have not yet experienced one. Eilrich, Doeksen, and St. Clair (2015) extend the multiplier-based framework to estimate job and labor income losses associated with 16 rural hospital closures.

-

3

I distinguish a hospital by the presence of inpatient beds and consider only short-term acute-care facilities. Hospital data come from cost reports submitted annually by each hospital to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Data on annual county employment and aggregate wages are from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages.

-

4

I index the county data so that a closing in one year is economically equivalent to a closing in any other year. For counties without hospital closures, the equivalent to a closing date is the 2011–16 average, weighted by the share of hospitals that closed in each year. Three years before closure is the 2007–10 weighted average, and three years after closure is the 2015–18 weighted average. The sample includes all counties that do not have a town with 10,000 or more residents.

-

5

I conduct the same analysis using only counties with hospitals as comparison counties. The results are largely identical, though aggregate wage growth is moderately slower post-closure in comparison counties.

References

American Hospital Association (AHA). 2019. “External LinkRural Report: Challenges Facing Rural Communities and the Roadmap to Ensure Local Access to High-Quality, Affordable Care,” February.

Eilrich, Fred C., Gerald A. Doeksen, and Cheryl F. St. Clair. 2015. “External LinkThe Economic Impact of Recent Hospital Closures on Rural Communities.” National Center for Rural Health Works, July.

Ellison, Ayla. 2018. “External Link450 Hospitals at Risk of Potential Closure, Morgan Stanley Analysis Finds.” Becker’s Hospital Review, August 20.

Gulliford, Martin, Jose Figueroa-Munoz, Myfanwy Morgan, David Hughes, Barry Gibson, Roger Beech, and Meryl Hudson. 2002. “External LinkWhat Does 'Access to Health Care' Mean?” Journal of Health Services Research & Policy, vol. 7, no. 3, pp. 186‒188.

Holmes, George M., Rebecca T. Slifkin, Randy K. Randolph, and Stephanie Poley. 2006. “External LinkThe Effect of Rural Hospital Closures on Community Economic Health.” Health Services Research, vol. 41, no. 2, pp. 467–485.

Mosley, David, and Daniel DeBehnke. 2019. “External LinkRural Hospital Sustainability: New Analysis Shows Worsening Situation for Rural Hospitals, Residents.” Navigant, February.

Kelly D. Edmiston is a senior economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City or the Federal Reserve System.