Steve Shepelwich speaks Swahili. He once entered a vetiver-based project in the miscellaneous forage crop category in an Oklahoma county fair…and won. He has a plethora of farm animals on his property in Norman, Oklahoma. He’s helping to eradicate malaria from Africa. He drives a 1980s Volkswagen bus. He often thinks about returning to India.

Steve Shepelwich, lead community development advisor for the Kansas City Fed, is a Connector on an epic scale, fueled by relationships formed through wide-ranging interests and a deep desire to help. One thing about Connectors, though: unless you know what to look for, they can be hard to spot. They often fade into the background. Connectors observe, see an opportunity to make an introduction, make the introduction and…disappear. But as they quietly walk away, they leave behind them the start of something that otherwise would not have happened.

Shepelwich has been making connections throughout Oklahoma and the Federal Reserve System since he began working here almost 20 years ago. “It's just being curious and open and thinking about things,” he said. "When I was working in Kenya, you always looked for where different systems rubbed up against each other. It’s like when you're driving in a rural area, you see the pristine wheat fields. It's all wheat. But where is it really interesting? It's at the fence rows, where the fields come together. That's where the rabbits hide. That's where all the weeds are. That's where the wildflowers are, too. Where systems rub up against each other is where you look to see where something interesting is happening.”

Shepelwich is a life-long community development pro, whose journey from great-grandson of Russian and Polish immigrants to marketing student to Peace Corps volunteer to that interesting man in Oklahoma is full of twists and turns, a willingness to challenge his own perceptions, and a desire to connect.

His great-grandparents were immigrants who settled in Texas

“At one point, about every Shepelwich in America lived on the north side of Fort Worth,” Shepelwich said. His great-grandparents were part of a wave of immigrants from Russia and Poland who found work in the stockyards, slaughterhouses, and processing plants on Fort Worth’s north side.

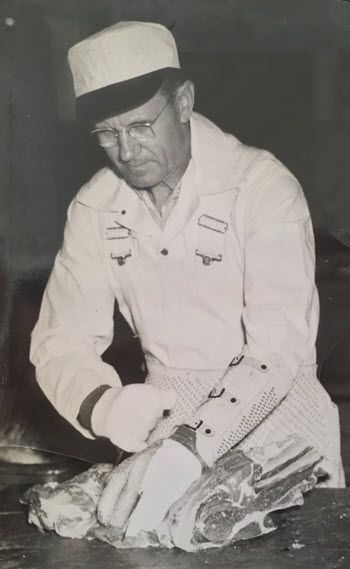

Steve's great-grandfather, "Grandpa Shep," came to the U.S. from Poland in 1907 and worked at Swift & Co. for 50 years.

Shepelwich knew three of the four great-grandparents that came from Russia and Poland very well. They spoke the languages and shared traditions from their home countries and sparked his interest in other cultures. It was his dad, though, who sparked his interest in small towns. He sold lumber to small lumber yards around North Texas, and often took his young son with him.

Three generations of Shepelwiches: Steve's grandma and grandpa, his father, and his great-grandmother and great-grandfather.

That big white truck sold him on marketing

For college, Shepelwich chose Texas A&M, not too far from home, but he had no idea what to choose for a major. Then he remembered a recent college graduate from his town. “This kid had just graduated with a marketing degree and got a job and bought himself a brand new big white truck,” Shepelwich said. “So I chose marketing.”

It was a slow start. “I wasn't really into it in the beginning,” Shepelwich said. “Then I read an article by Peter Drucker, who said that marketing was the greatest force for social change in the 20th century. And I thought, wow, that's a big statement. I stayed in the marketing program just to see if that was true.”

Going to India was a “complete fluke” and a life-changing experience

Junior year, Shepelwich went to the career placement office, looking for a job. He had the choice of two big binders of opportunities. One was internships and fellowships, the fancy stuff. The other held your standard, everyday jobs. That’s the one he grabbed.

“I was flipping through jobs,” Shepelwich said. “It was sacking groceries, working at a hotel front desk, going to India for six months, doing lawn care. And I stopped.” The job in India belonged in the other folder. Nothing about it was standard.

The job was with a nonprofit community development organization, a village-based project based on Gandhi’s work. “The day I met the director, he basically said, ‘You are a young American college student, and you want to change the world, but you really can't do anything in six months. So just listen and learn. You'll do something for somebody else further on.’ That was freeing,” Shepelwich said.

The director encouraged experiences such as visiting a hospital for people with leprosy and joining the veterinarian on his rounds of dairy cattle. “It was such a different type of life, it shatters conceptions,” Shepelwich said. “You realize the world can be completely different than whatever you see in front of you.”

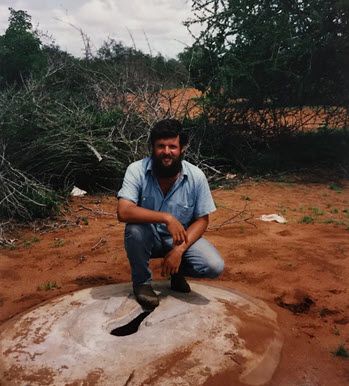

While in Kenya, in five months Shepelwich and others built some 14,000 pit latrines in Somali refugee camps.

It was about so much more than the water tanks

From India, Shepelwich returned to Texas to finish his degree. Then, still hungry to make a difference, he joined the Peace Corps. His assignment: rural Kenya, a farming community in an area newly settled after independence. He helped with planning, pricing, and marketing for cooperative businesses. The project he enjoyed most began when he gave a speech that bored a bunch of women.

“I was talking to this women’s group about business planning,” Shepelwich said. “It was obvious that everybody was completely bored but that’s what I was invited to talk about. I stopped and said, ‘What do you really want to talk about?’ And they start talking about water and access to water.” The conversation continued over several months. The women did their research and settled on the idea of each house having its own rainwater catchment tank. They got to work.

Most of the water tanks were destroyed during civil strife after an election five years later. “But the act of those women coming together and working together and figuring out how to do it,” Shepelwich said, “that made a difference in their lives and put them in a different place to respond to that emergency. The water tanks weren’t the real issue.”

Listening to residents offers surprising insights

As Shepelwich watched men leave the village to take jobs in the city, he wanted to know more about their lives. He found a Peace Corps position in Nairobi. While he understood the need for people to move there for stable employment, access to health care and such, “it was definitely not a pretty spot, the slums of Nairobi.”

Peace Corps training encouraged a participatory approach. In Nairobi, Shepelwich talked to residents about the slum, called Korogocho, how it developed, how they saw it. “By some accounts, Korogocho meant ‘chaos,’” Shepelwich said. “While it seemed that way on the surface, I was surprised by the ways people organized themselves to make it all work. While people struggled immensely, there was community and history there, connections among themselves and with the broader world, and some sense of hope and expectation. While that all seems obvious and self-evident to me now, it was not my expectation when I moved there.”

From the slums of Nairobi to rural Delaware, people are pretty much the same

The Nairobi program followed the External LinkGrameen Bank model, which alleviates poverty and empowers the poor through microcredit. (Grameen Bank received the Nobel Peace Prize in 2006.)

From Nairobi, Shepelwich returned to the U.S. to join a similar microcredit program in rural Delaware, with similar incentives and rules. “It was fascinating that the way individuals responded to the rules were basically the same both in rural Delaware and Nairobi,” he said. “It was stunning how the reactions were so similar.”

Oklahoma felt like a good fit

From rural Delaware, Shepelwich moved to Washington, D.C., where he worked at a national think tank. By this time, he was married to his wife, Inger Giuffrida, and they had two children, Sam and Sofia. He and Inger met in Kenya when both were in the Peace Corps. He wanted to move closer to Fort Worth and he wanted to have an impact his children could see. “I wanted to be local, to be able to drive around and show my kids, there's a project we're working on.”

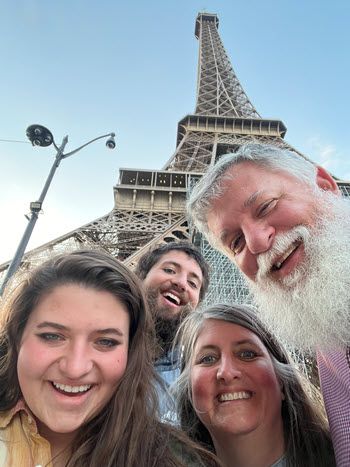

Sofia, Sam and Steve Shepelwich strike a pose.

He had just turned 40 when the Kansas City Fed hired him to be the first community development advisor at its Oklahoma branch, focusing on workforce development. In the 19 years since then, Shepelwich has become known for his deep roots in Oklahoma, and for his extensive involvement in national, System-wide projects. No matter the place or project, he is known for playing the role of connector.

A quick explanation about the Federal Reserve System

The Federal Reserve System is divided geographically into 12 Districts, each with its own Reserve Bank that is separately incorporated. The Districts don’t always follow state lines, but were drawn to reflect how trade flowed in 1913, when the System was formed. Each Reserve Bank operates independently, but all are supervised by the Federal Reserve Board of Governors. Over time, the 12 Reserve Banks have operated with an increasing amount of collaboration and coordination. Today, community development staff members often serve on cross-System learning committees and work groups and participate in collaborative projects and events.

Shepelwich finds a home with Fed Communities

In 2017, Federal Reserve System presidents turned to senior leaders in community development and public information. They asked them to find a way to tell stories of the Fed’s work in communities, stories that might provide a balanced picture of the institution.

The senior leaders, with Shepelwich as project manager, hired a communications consultant. One finding was that most community development professionals had no knowledge of the Fed’s work in low- and moderate-income communities. The other was that when they learned about that work, their perception of the Fed changed for the better. The group proposed forming a storytelling unit at the Fed to tell accessible, people-focused stories about the Fed’s work in communities. From that, External LinkFed Communities was born.

Anne O'Shaughnessy is communications director, Fed Communities.

“Steve has grown in influence and stature,” Anne O’Shaughnessy, Fed Communities communications director, said of his role. When the senior leadership group decided it should function as a steering committee, they asked Steve to join as a full-fledged member. “Steve has always been so incredibly valuable because of his deep knowledge, his ideas and insights and his ability to make connections.”

O’Shaughnessy credits Shepelwich for Fed Community’s first deep-dive story, about External LinkInvestment Connection. A profile, he told her, “is another way to show that not only are banks leveraging the Community Reinvestment Act to invest in communities, but the Fed is acting as a change agent, bringing players together.”

She calls Shepelwich the elder statesman of Fed Communities “and everyone’s favorite uncle, because he’s just so approachable. He’s curious about the world, an interested and interesting human.”

At an Investment Connection event in Tulsa, Steve Shepelwich shares a laugh with two participants.

Helping Tenth District workers avoid benefits cliffs

Because of something called External Linkbenefits cliffs, taking even the smallest raise can result in a low-wage worker losing thousands of dollars in government benefits. “We look at individuals making these decisions, like not to move up in their job, and we often blame people for that. Like, that's stupid, it's short sighted,” Shepelwich said. “But they're facing a completely different set of risks than most people realize.”

In 2018, Shepelwich heard that the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta was developing a tool to help workers manage the impact of benefits cliffs over time, with figures customized for their geographic area. He was intrigued. He volunteered to help the Atlanta Fed test External LinkCLIFF – Career Ladder Identifier and Financial Forecaster by connecting with agencies in the Tenth District.

“For years, people talked about the benefits cliffs, but there was no real clear way of addressing them,” Shepelwich said. “Then the Atlanta Fed developed this tool that is clear, straightforward, intuitive, and useful. And it shows what the Fed can do as a system, with the Atlanta Fed developing the tool, and us bringing that whole new resource into our district.”

Alexander Ruder is Community and Economic Development (CED) director and principal adviser for the Atlanta Fed’s CED team.

Shepelwich worked with Alexander Ruder, Community and Economic Development (CED) director and principal adviser for the Atlanta Fed’s CED team. Ruder is one of a couple of leads on the CLIFF project. “Steve was able to bring on some very strong nonprofit partners because of his connections in the community,” Ruder said. “He had the networks and knew what types of Federal Reserve resources would benefit those partners. Steve is an expert connector in terms of understanding what connections will add value to the various partners.” (While the Atlanta Fed makes CLIFF available at no charge, it does not provide grants or other funding to organizations that partnered with it to pilot the CLIFF tool.)

But Ruder says Shepelwich provided more than just connections. “Steve went beyond connecting with CLIFF, he was actively involved in implementation and expansion of this work. He’s not just a connector, he’s a practitioner in the field of community development.”

Shepelwich connects Oklahoma to Reinventing Our Communities

“I enjoy finding connections for Oklahoma in particular,” Shepelwich said. When he heard about the Philadelphia Fed program, External LinkReinventing Our Communities [ROC], he contacted Michelle Bish, executive director of the External LinkNortheast Workforce Development Board. “They jumped on it and brought together about ten different organizations to work on childcare issues.”

The Philadelphia Fed designed the ROC Cohort Program to encourage strong local economies by helping communities address structural racism and barriers to economic mobility. Cohorts are groups of cross-sector community leaders who participate in activities that allow them to create a tailored racial equity plan to address local challenges. The 2022 ROC cohort included 11 communities in 10 states and eight Reserve Bank regions.

Michelle Bish is executive director of the Northeast Workforce Development Board in Catoosa, Oklahoma.

The group drilled down and pulled the data. “We started looking at the inequities in childcare and disparities that had an even greater impact because of the pandemic, especially in Oklahoma,” Bish said. “For a moment, it felt overwhelming, but you take it one step at a time, and you make an impact where you’re able to.” One result of their work: The state’s career training program, External LinkCareerTech, developed an early child education program. “It results in certification, so that was a huge win,” she said. They can pay individuals to take the training with funding from the Workforce Innovation Opportunity Act.

While the national ROC cohort met virtually, the Oklahoma team decided to meet monthly in person. “Steve was incredibly engaged over the duration of our cohort,” Bish said. “He came to most of our in-person meetings. He brings the presence of the Federal Reserve with him, which people appreciate and respect, but he does it in the way that only Steve Shepelwich can, with such humility. People listen when he speaks.”

The Kansas City Fed appointed Bish to the Community Development Advisory Council in 2023. “There are people you meet in your professional life that truly have an impact on you,” Bish said. “Steve absolutely is a connector. I think his heart is just to help people, and you do that by connecting the resources. Steve just gets it. He understands. It’s a core part of who he is.”

Shepelwich conducts workforce outreach with the Comanche Nation.

The Proust Questionnaire

The Proust Questionnaire was popularized by External LinkMarcel Proust and, more recently, External LinkVanity Fair magazine. Answers by Steve Shepelwich.

What is your idea of perfect happiness? Helping people I love be happy.

What is your greatest fear? Being irrelevant.

What is the trait you most deplore in yourself? Need for approval.

What is the trait you most deplore in others? Talking over other people.

Which living person do you most admire? The one I see showing kindness when they don’t have to.

What is your greatest extravagance? I allow myself to hold on to the hope unicorns aren’t yet extinct.

What is your current state of mind? Classic monkey mind.

What do you consider the most overrated virtue? Decisiveness.

On what occasion do you lie? When answering questionnaires.

What do you most dislike about your appearance? It’s different than I think it is.

Which living person do you most despise? They know who they are.

What is the quality you most like in a man? Sense of humor.

What is the quality you most like in a woman? Sense of humor.

Which words or phrases do you most overuse? ‘That’s great.’

What or who is the greatest love of your life? Inger, my wife.

Sofia, Sam, Inger and Steve pose in front of a familiar French landmark.

When and where were you happiest? I love being in the middle of a chaotic place where I don’t speak the language, don’t have a clue what is going on, and no idea what is going to happen next.

Which talent would you most like to have? Time travel.

If you could change one thing about yourself, what would it be? I’d act sillier.

What do you consider your greatest achievement? Helping create a family that loves just being together and makes time for it.

If you were to die and come back as a person or a thing, what would it be? A pigeon.

Where would you most like to live? Old Delhi or Montana.

What is your most treasured possession? Memories and dreams.

What do you regard as the lowest depth of misery? Living in fear and hopelessness.

What is your favorite occupation? Anthropologist (the Indiana Jones kind).

What do you most value in your friends? Their gift of presence and time.

Who are your favorite writers? Hemingway, Steinbeck and Kerouac, though I doubt I will ever read them again.

Who is your hero of fiction? Chief Bill Gillespie, Sparta Police (the TV version).

Which historical figure do you most identify with? Teddy Roosevelt.

Who are your heroes in real life? My great grandparents who immigrated to the US and made a life in a new and strange place.

What are your favorite names? Sam and Sofia.

What is it that you most dislike? Olives.

What is your greatest regret? I was talked out of taking the Khulna Rocket steamer from Dhaka to the Sunderbans in Bangladesh.

How would you like to die? Expectant.

What is your motto? We make the road by walking.