Payment inclusion refers to a consumer’s ability to access safe and low-cost payment services as needed. This type of access requires ownership of a transaction account, such as a bank account or prepaid card; without a transaction account, consumers must rely on slow and costly paper-based payment services such as check cashing and money orders. By enabling consumers to make and receive payments more safely, cheaply, and efficiently, payment inclusion may allow consumers to participate in the economy more fully and enhance their economic well-being.

Both public- and private-sector entities have engaged in efforts to advance payment inclusion since the 1970s and the number of payment inclusion programs and initiatives has grown substantially over time. In this briefing, I provide an overview of existing and proposed payment inclusion efforts in the United States, including initiatives to expand the supply of transaction accounts and efforts to boost consumer demand for transaction accounts. I also review the difficulty in assessing the effectiveness of these measures and potential areas for future research.

Maintaining and expanding the supply of safe, low-cost transaction accounts

Many researchers and policymakers consider having a transaction account—a bank account, a prepaid card, or a nonbank transaction account such as a PayPal or CashApp account—to be a gateway to payments inclusion. Both the public and private sectors are actively engaged in efforts that directly or indirectly promote the availability of safe, low-cost transaction accounts.

Increasing access to traditional bank accounts for underserved communities

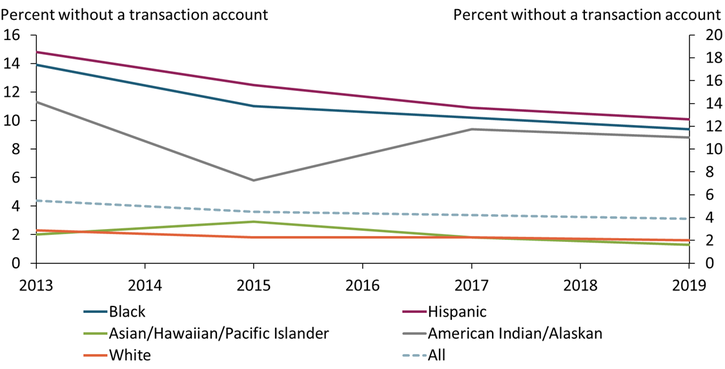

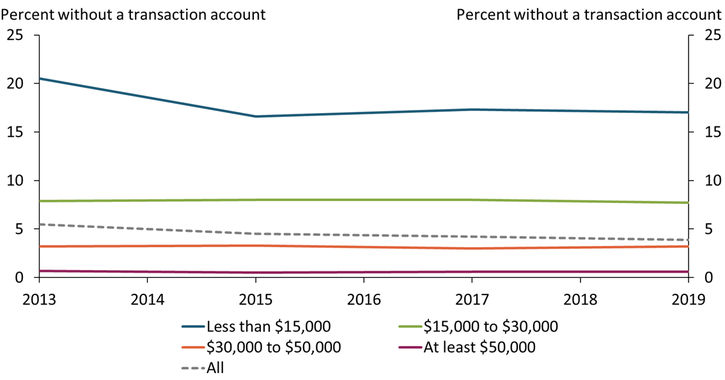

Low- to moderate-income (LMI) and racial minority communities tend to face more challenges and barriers to accessing safe, low-cost transaction accounts and are thus more likely to face payment exclusion. As Charts 1 and 2 show, Black, Hispanic, and Native American/Alaskan consumers and low-income consumers are substantially more likely to lack a bank account or prepaid card than their white, higher-income counterparts, and these gaps in ownership have been persistent.

Chart 1: Despite a general decline, racial gaps in transaction account ownership persist

Source: FDIC.

Chart 2: Income gaps in transaction account ownership persist

Sources: FDIC and author’s calculations.

The sparsity of financial institutions and higher cost of banking services in LMI communities may contribute to their higher payment exclusion rates._ Many financial institutions do not find serving these communities profitable, and as large banks seek to consolidate branches, they have closed branches disproportionately in lower-income neighborhoods, pulling out of some of these neighborhoods altogether (Davis 2019).

Rural communities also face higher risks of losing ready access to banking services with bank branch consolidation. Although rural areas have experienced a smaller percentage loss of bank branches than urban areas, they tend to face a larger reduction in the accessibility of banking services when bank branches close, due to their larger geographical size and lack of public transportation (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System 2019)._ Moreover, rural consumers rely more heavily on bank branches than their urban counterparts and are more likely to be digitally excluded, meaning they may not be interested in or be able to switch to online banking alternatives (CFPB 2022).

Federal regulatory agencies for depository institutions and the U.S. Treasury have launched several programs and initiatives to support federally regulated financial institutions that offer depository accounts mainly to racial minority and LMI consumers. Examples of these programs and initiatives include the Minority Depository Institution (MDI) program run by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), the Community Development Financial Institutions (CDFI) Program supported by the U.S. Treasury, and the Low-Income Credit Union (LICU) designation offered by the National Credit Union Administration (NCUA)._ The NCUA also actively encourages eligible federal credit unions to expand membership to underserved communities and rural districts regardless of geographical locations (Hood 2021). To enable more credit unions to expand their membership to underserved populations, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a bill in June 2022 that seeks in part to amend the Federal Credit Union Act to broaden the eligibility for all types of federal credit unions._ If implemented, this amendment may help improve access to transaction accounts in LMI, minority, and rural communities.

The private sector has also introduced initiatives to improve the availability and accessibility of low-cost bank accounts to underserved consumers. A notable example is the Bank On movement, which certifies bank accounts that meet their National Account Standards (a set of requirements for an account to be considered safe and low-cost) and collaborates with local governments, financial institutions, and nonprofit community organizations to connect unbanked consumers with these low-cost accounts._ According to data collected by the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, 3.8 million of these accounts were open and active in 2020; as of September 2022, over 46,000 bank and credit union branches across all 50 states offer Bank On accounts. Another example is the Alliance for Economic Inclusion (AEIs), coalitions of local financial institutions, community organizations, and government that help promote financial inclusion by connecting underserved communities with the mainstream financial system. The Kansas City AEI, for instance, has initiated working groups focused on increasing access to banking services for its minority and immigrant communities.

Expanding the offerings of safe, low-cost nonbank transaction accounts

Although improved access to low-cost bank accounts for underserved consumers has likely helped reduce barriers to bank account ownership, some consumers may remain unbanked for other reasons, such as a lack of trust in banks. To serve these consumers, the private sector has introduced several nonbank transaction account alternatives. The oldest form of nonbank transaction account is arguably the general purpose reloadable (GPR) prepaid card, which many researchers and policymakers have considered a basic checking account substitute (for example, see Anong and Routh 2022 and Villafranca 2010). Consumers can easily own GPR prepaid cards because no banking history check and no minimum deposit are required. The funds are generally FDIC-insured, and they have large cash-in/cash-out networks, including major retail stores and pharmacies. Despite these features, prepaid cards have not been very successful at attracting or retaining underserved consumers, partly due to relatively high fees charged to the cardholders (Toh 2021)._ Efforts by government agencies to offer low-fee prepaid cards (such as the Direct Express card) as an option for receiving government benefits appear to increase prepaid card ownership among the underserved population, but their overall effect on prepaid card ownership is small._ Looking ahead, new and improved prepaid card offerings entering the market may make prepaid cards more attractive to consumers. Some providers now charge lower or no transaction fees and may even offer benefits such as cash back rewards (for example, Kroger’s Rewards prepaid card) and free life insurance and mobile device protection (T4L’s prepaid card program).

More recently, fintech transaction account options have also been growing as neobanks and payment platforms such as PayPal and Cash App enter the banking space._ Like GPR cards, fintech accounts tend to come with fewer barriers to adoption and are often covered by FDIC deposit insurance._ Additionally, many fintech account providers tailor their services to meet the needs of underserved consumers (who tend to be more cashflow-constrained) by offering features such as early availability of funds from direct deposits, interest-free cash advances, and same-day check deposit (Bradford 2020). Some fintech providers also offer helpful financial management tools (such as budgeting, saving, and debt management tools), which may further boost their appeal to underserved consumers. Although promising, fintech accounts are likely to address the problem of financial exclusion only partially. Fintech accounts are typically digital accounts, and some underserved consumers may lack the technologies (such as smartphone and internet access) or savviness needed for accessing these accounts.

Crypto wallets are another emerging form of alternative transaction accounts. Although most crypto owners have, to date, held crypto purely for investment purposes, consumers who own crypto but lack a bank account, a credit card, or retirement savings tend to hold crypto for transaction purposes. This suggests that some underserved consumers find the crypto payment system more accessible and appealing than the traditional payment system (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System 2022a; Bradford 2022). In the longer term, crypto may have the potential to enhance payment inclusion; however, the current risks of transacting with crypto likely outweigh the benefits. Poor consumer understanding of crypto, lack of regulation and consumer protections, and limited use cases all reduce the net benefit of using crypto for transactions.

Proposals for creating public banks and central bank digital currency (CBDC)

Because private sector transaction account offerings may have limited effects on increasing the availability of low-cost transaction accounts for underserved consumers, many policymakers, consumer advocacy groups, researchers, and others call for the creation of banks operated by public entities. These banks could offer consumers basic financial services tailored to the needs of the underserved population (Bostic and others 2020). Public banking proposals fall into three prominent categories: postal banking; state, municipal, or tribal banking; and Treasury-issued accounts and digital currency.

Postal banking entails providing basic financial services through the United States Postal Service (USPS). The USPS operated the Postal Savings System from 1911 to 1967, but postal banking has received renewed interest among academics and policymakers over the past decade, particularly since the onset of the pandemic._ Proponents of postal banking argue the USPS could leverage its large network of post offices to improve physical access to banking services, particularly in areas that do not have a bank or credit union branch._ However, some are skeptical about the importance of proximity to a bank branch for payment inclusion, noting that only 2.1 percent of unbanked consumers in the 2019 FDIC survey cited inconvenient bank locations as their main reason for being unbanked (Gattuso and Pigéon 2019).

State, municipal, or tribal banking involves creating government-chartered public banks that are mandated to serve the public interest (Krishnamurthy and Cochenour 2022). Ideally, these public banks would offer low- or no-fee checking and savings accounts with no minimum balance requirements to consumers. However, services are limited; the only state-run bank in the United States, the Bank of North Dakota, provides basic checking and savings accounts and loans but does not offer debit card and online bill payment services, and the forthcoming municipal bank in the city of Philadelphia will not be offering checking or savings accounts initially.

More recently, researchers and policymakers have also explored the possibility of Treasury-run transaction accounts and digital currency. One proposal involves the Treasury offering basic digital accounts that it can use to distribute federal benefits and provide eligible consumers with low-cost payment and savings services (Jackson and Massad 2022). A second proposal—inspired by the success of the Treasury-run prepaid card program for receiving federal benefits, the Direct Express card program—calls for the Treasury to create Liberty accounts (and cards), which would effectively expand access to Direct Express cards to all U.S. residents (Krishnamurthy and Cochenour 2022)._ A slightly different proposal—the Electronic Currency and Secure Hardware (ECASH) Act—calls for the Treasury to issue a digital dollar that would serve as the electronic version of cash. To address financial inclusion, the bill mandates that e-cash has several features, including reliance on technologies that are universally accessible and usable, offline capabilities, and interoperability with all financial institutions and payment service providers.

Related to proposals for public banking are calls for the Federal Reserve to issue a central bank digital currency (CBDC). In exploring the possibility of issuing a CBDC, the Federal Reserve Board is considering financial inclusion as a potential benefit (Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System 2022b). Payment (or financial) inclusion is a key motivation for issuing a CBDC in countries that have already implemented or are currently implementing a CBDC (such as the Bahamas, China, and Mexico), so a CBDC could potentially improve payment inclusion in the United States, if it is properly designed for that goal._ For instance, if consumers could access CBDC through a CBDC account or wallet app offered by nonbanks or public banks without having traditional bank accounts, account access among underserved consumers could increase. However, because design features that would help promote financial inclusion may not be compatible with other central bank objectives, whether a U.S. CBDC could improve financial inclusion if implemented remains to be seen (Maniff 2020b).

Increasing consumer demand for transaction accounts

Even if they have access to transaction accounts, some consumers may be hesitant to adopt them or not fully understand the benefits. Government agencies, nonprofit organizations, and businesses have been trying to improve consumers’ financial literacy and encourage their adoption of transaction accounts through financial education and consumer outreach._ At the federal level, Congress established the interagency Financial Literacy and Education Commission (FLEC) and tasked it to develop a nationwide strategy to advance financial literacy and education, coordinate financial education efforts across federal agencies, and promote cross-sector collaborations. To that end, the FLEC established a toll-free hotline and a website, MyMoney.gov, which serves as a clearinghouse for financial education resources offered by its member agencies (Jones 2007). Many private sector organizations (for example, nonprofit organizations like Operation HOPE and businesses like the education technology firm EverFi) have also developed their own financial education programs—some with financial coaching—provided directly to consumers and through partnerships with employers, financial institutions, and other social institutions. Fintechs are also increasingly active in the financial education space, leveraging technology and gamification techniques to deliver more engaging and personalized financial education content to consumers._ In addition to financial education, many organizations are engaged in multimedia consumer outreach, particularly on social media platforms. An example is the FDIC’s “#GetBanked” campaign, which seeks to increase consumer awareness of the benefits of having a bank account.

Consumers’ trust in the payment system is also crucial to encouraging the adoption of transaction accounts. To this end, governmental agencies have been actively supervising and regulating payment products and services to protect consumers from potential harms in the payment market (such as hidden fees and privacy violations). Examples of regulations include the CFPB’s prepaid card rule in Regulation E (the Electronic Fund Transfer Act), which mandates clear disclosure of certain fees and liabilities by prepaid card issuers; Regulation DD (the Truth in Savings Act), which governs information disclosures for deposit accounts by depository institutions; Regulation P (the Gramm-Leach-Bliley Act), which protects the privacy of consumers’ nonpublic financial information obtained by financial institutions; and state-issued caps on overdraft fees (as in New York, Massachusetts, and Illinois)._ In addition to enforcing regulations, the CFPB also provides supervisory guidance to financial institutions on issues relating to consumer financial protection. Regulation, however, often lags innovation; fintech transaction accounts and crypto wallets are examples of new products that are not subject to clear regulations. As these new products often attract underserved consumers who tend to be more financially vulnerable, addressing the lack of consumer protection in the time between the introduction of a new payment product and the passage of regulation may be critical to promoting payment inclusion.

Understanding payment exclusion, developing strategies, and evaluating payment inclusion efforts

In addition to efforts to enhance the safety, affordability, and appeal of transaction accounts for consumers, many governmental and private sector agencies focus on research and experimentation to better understand the underserved population and test out potential solutions to payment exclusion. For example, the FDIC and the Federal Reserve conduct consumer surveys, interviews, and focus groups to collect data and monitor trends on consumer use of banking, payment, and other financial services. The CFPB frequently conducts inquiries into business practices and products offered by financial institutions and nonbanks, collecting information on their risks and benefits to help guide regulatory and supervisory efforts. To evaluate the feasibility or effectiveness of certain financial products or services for increasing payments inclusion, the CFPB and FDIC have also conducted randomized control trials and pilot studies._ Using these data, researchers have analyzed and written on the issue of payment exclusion to promote our understanding of the problem and inform payment inclusion efforts._

Although existing research and experimentation efforts have helped guide payment inclusion strategies, more can be done to further our understanding of the underserved population and improve payment inclusion strategies. One critical area where more research is needed is in defining and measuring payment inclusion. Researchers commonly use the unbanked rate, or share of consumers without a bank account, as a proxy for payment inclusion, but the unbanked rate likely overstates the true extent of exclusion because it does not consider consumer adoption of nonbank transaction accounts, which are increasingly prevalent. Data on consumers’ adoption of nonbank transaction accounts is also lacking, making it nearly impossible to measure payment inclusion. Developing a comprehensive, universal definition of payment inclusion and collecting data on nonbank transaction account ownership and usage are crucial to informing payment inclusion strategies.

Another area where more research is needed is in evaluating past and current payment inclusion efforts. Organizations involved in these efforts often lack measurable goals and objective assessments of the effectiveness of their payment inclusion efforts (Government Accountability Office 2022; Jones 2007). For example, regulators have not evaluated whether and how much MDIs, CDFIs, and LICUs affect payment inclusion and whether they fulfill comparable roles in promoting payment inclusion. Similarly, while Bank On provides data showing the increase in offerings of Bank On accounts, it has not assessed consumers’ adoption of these accounts. Evaluating the effectiveness of payment inclusion efforts is an important next step for organizations involved in these efforts as it helps not only to inform the strategy for payment inclusion going forward but also to allocate resources more efficiently._

Conclusion

Although efforts to expand access to and increase demand for transaction accounts seem to have contributed to bank account ownership overall—data from the Survey of Consumer Finances show that the share of unbanked households has been declining for the past two decades—their effect on payment inclusion cannot be determined without a well-defined measure of payment inclusion, data on consumer adoption of nonbank transaction accounts, and objective performance measures. Despite the research efforts, gaps in our understanding of the underserved population remain. More research is needed to understand the persistent bank account ownership gaps across racial and income groups and underserved consumers’ adoption of nonbank transaction accounts and services and their payment behaviors. Filling these data and research gaps is a critical next step to advancing payment inclusion in the United States.

Endnotes

-

1

A 2020 Bankrate survey found that Black and Hispanic consumers pay more than twice as much in bank fees compared with white consumers (Fox 2021).

-

2

Dahl and Franke (2017) found that rural areas are more likely to become “banking deserts”— census tracts without a bank branch within a 10-mile radius of the tract’s center—due to bank branch closures.

-

3

The FDIC defines an MDI as “any federally insured depository institution for which (1) 51 percent or more of the voting stock is owned by minority individuals; or (2) a majority of the Board of Directors is minority and the community that the institution serves is predominantly minority. Ownership must be by U.S. citizens or permanent legal U.S. residents to be counted in determining minority ownership” (FDIC 2022). The CDFI Coalition defines CDFIs as “private-sector, financial intermediaries with community development as their primary mission” (CDFI Coalition 2022). For a credit union to qualify for the LICU designation “a majority of the credit union’s membership must meet certain low-income thresholds based on data available from the U.S. Census Bureau” (NCUA 2021). The number of certified CDFIs has grown from 153 in 1996 to over 500 in 2020, suggesting success in the CDFI program, but the number of MDIs declined from 215 in 2008 to 143 in 2021, and the decline is particularly sharp for Black-owned MDIs—only 19 Black-owned MDIs remain in 2021, down from 41 in 2008. Note that a decline in the number of MDIs does not necessarily mean that efforts to support MDIs have been ineffective, as there is a general trend of consolidation in the banking industry during this period.

-

4

The bill is the Federal Reserve Racial and Economic Equity Act (H.R. 2543).

-

5

Consumers can use the list of certified Bank On accounts (available at Bank On’s website) to find financial institutions that offer Bank On accounts near them.

-

6

Hayashi and Cuddy (2014) estimated that NetSpend prepaid card users incurred between $14 to $17 per month in fees, likely a considerable amount for many prepaid card users.

-

7

According to data from the FDIC, only 15 percent of prepaid card users in 2017 obtained their cards from a government agency (Apaam and others 2018). Moreover, recent exits of commercial banks from government-administered prepaid card programs have curtailed recipients’ ability to receive their benefits via prepaid cards in two states.

-

8

Many of these transaction accounts are digital accounts (accessible only online or via a mobile app), targeting underserved consumers who are more technology savvy.

-

9

Fintech firms typically deposit consumers’ funds at an FDIC-insured depository institution. Some (but not all) PayPal accounts are FDIC-insured.

-

10

Several postal banking bills have been introduced in the U.S. Senate in the past few years, most recently in March 2022. The USPS also launched a limited check cashing pilot program at four of its locations in September 2021; however, the program had attracted only a few consumers as of January 2022 (Katz 2022). The USPS had planned to expand its pilot program in 2022 but was unable to obtain funding from Congress.

-

11

A study by the University of Michigan found that 69 percent of census tracts with a post office do not have a community bank branch and 75 percent of these census tracts do not have a credit union branch (Friedline and others 2021).

-

12

A key distinction between the Liberty card and the Direct Express card is that the Liberty card allows consumers to deposit funds on their card, while the Direct Express card does not.

-

13

Maniff (2020a) identified six design features for a CBDC aimed at improving financial inclusion based on the reasons why consumers are unbanked. Further, several emerging markets and developed economies have launched or are launching CBDCs with the explicit goal of increasing financial inclusion (Hayashi and Toh 2022). The features of these CBDCs may also provide insights into how a central bank could design a CBDC for financial inclusion.

-

14

Many policymakers and researchers believe that low financial literacy is a barrier to transaction account ownership and financial inclusion more broadly (Fernandes, Lynch, and Netemeyer 2014). Some further believe that financial education and introduction to financial services at a young age can lead to higher bank account ownership and better financial habits in adulthood, introducing several programs focus specifically on improving financial literacy and bank account ownership among youths (for example, the FDIC’s Youth Banking Resource Center). The OCC provides a directory of financial literacy and education resources offered by both the public and private sectors on its External Linkwebsite.

-

15

Notable fintechs that focus on financial literacy include ZOGO and Goalsetter. Both fintechs offer financial education tailored to their audience via mobile apps. ZOGO also partners with financial institutions to distribute its app, while Goalsetter partners with educators across different sectors.

-

16

At the federal level, some lawmakers are pushing for the passage of an overdraft protection bill (H.R.4277), which will set disclosure requirements relating to overdraft coverage, cap the number (per month) and amount of overdraft fees a financial institution can charge to an account, and define conditions under which a financial institution is prohibited from charging overdraft fees.

-

17

For instance, the CFPB has conducted several randomized control trials to evaluate tools for encouraging savings, and the FDIC has conducted a Youth Saving Pilot Program to help the agency to identify strategies to promote minor bank account ownership.

-

18

Boel and Zimmerman (2022) provided a survey of research studies relating to payment exclusion.

-

19

For example, federal agencies have devoted much effort to developing and maintaining financial literacy and education programs, but existing academic research generally finds little to no effects or mixed effects of financial education on consumers’ financial behaviors (for example, Fernandes, Lynch, and Netemeyer 2014 and Collins, Larrimore, and Urban 2021), suggesting that reallocating resources away from financial literacy and education programs toward efforts that are more effective may produce better payment inclusion outcomes. That said, more research may be necessary to examine whether the findings in the academic research extends to the financial literacy and education programs run by federal agencies—the effectiveness of financial education likely differs depending on how the program is designed and delivered. Better tailored financial education programs and more engaging content delivery methods may lead to stronger positive effects on financial behaviors and outcomes.

References

Anong, Sophia T., and Aditi Routh. 2022. “External LinkPrepaid Debit Cards and Banking Intention.” International Journal of Bank Marketing, vol. 40, no. 2, pp. 321–340.

Appam, Gerald, Susan Burhouse, Karyen Chu, Keith Ernst, Kathryn Fritzdixon, Ryan Goodstein, Alicia Lloro, Charles Opoku, Yazmin Osaki, Dhruv Sharma, and Jeffrey Weinstein. 2018. “External Link2017 FDIC National Survey of Unbanked and Underbanked Households.” Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation, October.

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. 2022a. “External LinkEconomic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2021.” May.

———. 2022b. “External LinkMoney and Payments: The U.S. Dollar in the Age of Digital Transformation.” January.

———. 2019. “External LinkPerspectives from Main Street: Bank Branch Access in Rural Communities.” November.

Boel, Paola, and Peter Zimmerman. 2022. “External LinkUnbanked in America: A Review of the Literature.” Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland, Economic Commentary, no. 2022-07, May 26.

Bostic, Raphael, Shari Bower, Oz Shy, Larry Wall, and Jessica Washington. 2020. “External LinkShifting the Focus: Digital Payments and the Path to Financial Inclusion.” Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, working paper no. 20-1, September.

Bradford, Terri. 2022. “External LinkThe Cryptic Nature of Black Consumer Cryptocurrency Ownership.” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Payments System Research Briefing, June 1.

———. 2020. “External LinkNeobanks: Banks by Any Other Name?” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Payments System Research Briefing, August 12.

CDFI Coalition. 2022. “External LinkAbout CDFIs.”

CFPB (Consumer Financial Protection Bureau). 2022. “External LinkData Spotlight: Challenges in Rural Banking Access.” April.

Collins, J. Michael, Jeff Larrimore, and Carly Urban. 2021. “External LinkDoes Access to Bank Accounts as a Minor Improve Financial Capability? Evidence from Minor Bank Account Laws.” Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Finance and Economics Discussion Series, no. 2021-075, November.

Dahl, Drew, and Michelle Franke. 2017. “External LinkBanking Deserts Become a Concern as Branches Dry Up.” Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Regional Economist, July 25.

Davis, Michelle F. 2019. “External LinkJPMorgan Leads Banks’ Flight from Poor Neighborhoods.” Bloomberg, March 6.

FDIC (Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation). 2022. “External LinkMinority Depository Institutions Program.”

Fernandes, Daniel, Lynch, John G. Jr., and Richard G. Netemeyer. 2014. “External LinkFinancial Literacy, Financial Education, and Downstream Financial Behaviors.” Management Science, vol. 60, no. 8, pp. 1861–1883.

Fox, Michelle. 2021. “External LinkBlack and Hispanic Americans Pay Twice as Much in Bank Fees as Whites, Survey Finds.” CNBC, January 13.

Friedline, Terri, Xanthippe Wedel, Natalie Peterson, and Ameya Pawar. 2021. “External LinkPostal Banking: How the United States Postal Service Can Partner on Public Options.” University of Michigan, Poverty Solutions, May.

Gattuso, James L., and Sean-Michael Pigéon. 2019. “External LinkWhy Postal Banking Would Help Neither the Poor nor the Postal Service.” The Heritage Foundation, July 26.

Government Accountability Office. 2022. “External LinkBanking Services: Regulators Have Taken Actions to Increase Access, but Measurement of Actions’ Effectiveness Could Be Improved.” Report to Congressional Requesters, no. GAO-22-104468, February.

Hayashi, Fumiko, and Emily Cuddy. 2014. “External LinkGeneral Purpose Reloadable Prepaid Cards: Penetration, Use, Fees, and Fraud Risks.” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Research Working Paper no. 14-01, February.

Hayashi, Fumiko, and Ying Lei Toh. 2022. “External LinkAssessing the Case for Retail CBDCs: Central Banks’ Considerations.” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Payments System Research Briefing, May 26.

Hood, Rodney E. 2021. “External LinkUnderserved Area Expansion.” National Credit Union Administration, Letters to Credit Unions and Other Guidance, 21-FCU-03, January.

Jackson, Howell, and Timothy G. Massad. 2022. “External LinkThe Treasury Option: How the U.S. Can Achieve the Financial Inclusion Benefits of a CBDC Now.” Brookings, March 10.

Jones, Yvonne D. 2007. “External LinkFinancial Literacy and Education Commission: Further Progress Needed to Ensure an Effective National Strategy.” U.S. Government Accountability office, testimony before the Subcommittee on Oversight of Government Management, the Federal Workforce, and the District of Columbia, Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, and U.S. Senate, April 30.

Katz, Eric. 2022. “External LinkThe Postal Service Has Provided Financial Services to Just 6 Customers through Its Banking Pilot.” Government Executive, January 14.

Krishnamurthy, Prasad, and Tucker Cochenour. 2022. “External LinkAn Economic Case against and for Public Banking.” SSRN, June 8.

Maniff, Jesse L. 2020a. “External LinkInclusion by Design: Crafting a Central Bank Digital Currency to Reach All Americans.” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Payments System Research Briefing, December 2.

———. 2020b. “External LinkMotives Matter: Examining Potential Tension in Central Bank Digital Currency Designs.” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Payments System Research Briefing, July 1.

NCUA (National Credit Union Administration). 2021. “External LinkLow-Income Designation.”

Toh, Ying Lei. 2021. “External LinkPrepaid Cards: An Inadequate Solution for Digital Payments Inclusion.” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Economic Review, vol. 106, no. 4, pp. 21–38.

Villafranca, Eloy. 2010. “External LinkBoosting Savings in Troubled Times.” Speech to National Conference of State Legislatures, Legislative Summit, Louisville, KY, July 27.

Ying Lei Toh is an economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City or the Federal Reserve System.