Recent events have heightened interest in a U.S. central bank digital currency (CBDC), a digital payments instrument denominated in dollars that would be a direct liability of the Federal Reserve (BIS 2020). Over the last year, efforts to implement a CBDC in other countries, digital currency projects in the private sector, and Economic Impact Payments (EIP) have all contributed to CBDC interest in the United States. The EIP process in particular revealed the challenges for U.S. payments systems in reaching all Americans, highlighting the need for further research into how best to reach the unbanked (George 2020).

Encouraging financial inclusion is one potential motivation for issuing a CBDC (BIS 2020; Barr, Harris, Menand, and Xu 2020). To address financial inclusion, a CBDC would first need to provide the unbanked with access to a transaction account (World Bank 2018)._ In addition, a CBDC would likely need to be designed around this goal, as a CBDC designed to address an alternative issue may conflict with or impede the goal of financial inclusion (Maniff 2020). This briefing does not take a position on whether a CBDC is the right instrument to reach the unbanked, but rather identifies the range of needs in the diverse unbanked population and how a CBDC may be designed to address them.

The Needs of the Unbanked

According to the 2019 Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) Survey of Household Use of Banking and Financial Services, 5.4 percent of U.S. households (approximately 7.1 million) do not have a checking or savings account and are thus considered unbanked. This is the lowest unbanked rate ever found in the survey, which started in 2009, and is 1.1 percentage points lower than the most recent survey from 2017. While the decline in the unbanked rate over the past decade is encouraging for the public policy goal of payment systems reaching all Americans, understanding why many households remain unbanked is crucial for developing solutions to reach them.

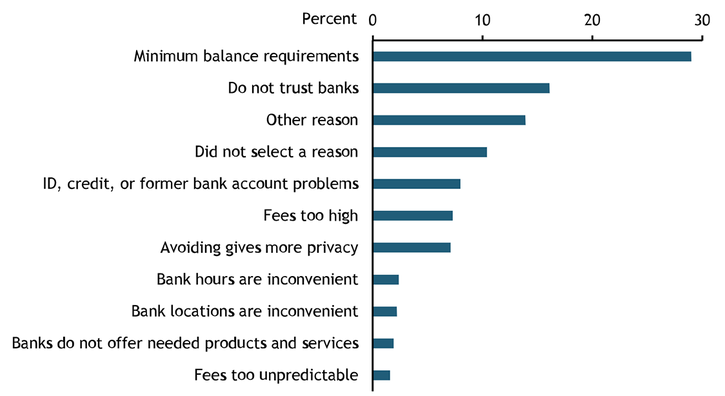

The FDIC survey has consistently found that reasons vary for why households are unbanked. Chart 1 shows unbanked households’ “main reason” for not having an account in 2019. The results are similar to those from the 2013 and 2015 surveys (Hayashi 2016; Maniff and Marsh 2017). Cost-related concerns, such as “don’t have enough money to meet minimum balance requirements,” “bank account fees are too high,” and “bank account fees are too unpredictable,” remain prominent reasons that households are unbanked. Many unbanked households also cite “personal identification, credit, or former bank account problems” and “avoiding a bank gives more privacy” as main reasons for being unbanked. Inconvenient hours and locations of banks also continue to be a problem for a few unbanked households.

Chart 1: Response to the 2019 FDIC Survey of Household Use of Banking and Financial Services: Main Reason for Not Having a Bank Account

Source: FDIC.

The second most-cited main reason for not having a bank account is “do not trust banks.” This is notable because “do not trust banks” is distinct from the “fees are too high,” “fees are too unpredictable,” and “avoiding gives more privacy” responses, suggesting another factor is causing unbanked households to distrust banks._ Thus, even if financial institutions address all of the other main reasons cited for not having a bank account, some unbanked households may still remain unbanked.

In addition, the manner in which unbanked households receive income affects their financial needs. In 2017, 26.5 percent of unbanked households received income by cash. Previous research has shown that how employees receive their pay strongly influences their banking status, with the unbanked twice as likely to be paid in cash as banked employees (Pew Health Group 2010). If unbanked households are able to operate entirely within a cash society, they may not have compelling reasons to open an account.

Even some unbanked households who receive income via checks or on prepaid cards may not be interested in having a bank account. According to the FDIC survey, a majority of unbanked households are not interested in having a bank account: 56.2 percent were “not at all” interested, while 18.9 percent were “not very” interested. Only 24.8 percent were “very” or “somewhat” interested in having a bank account. However, some of these households might be more inclined to change their banking status than others, depending on their reason for not having a bank account. For example, about one-third of “very” or “somewhat” interested unbanked households cited “don’t have enough money to meet minimum balance requirements” as their main reason for not having a bank account.

Whatever their reason for not having a bank account, unbanked households are significantly more likely to be excluded from digital payments than banked households (Toh and Tran 2020). Only 33.8 percent of unbanked households have home internet access, compared with 82.6 percent of banked households. Smartphone ownership among the unbanked is only 63.7 percent compared with 86.6 percent in banked households. Moreover, unbanked households are nearly twice as likely as banked households to have to cancel cell phone service due to cost (Pew Charitable Trust 2016). This means that smartphone ownership may not indicate whether an unbanked household would have consistent access to digital payments.

Addressing Needs and Access in a CBDC Design

A CBDC designed to address financial inclusion will have to address many, if not most, of the various reasons consumers cite for being unbanked. Unlike many of the current design proposals in circulation, this briefing does not take a stance on whether a public or private entity will offer CBDC accounts or whether a CBDC should be designed to be cash-equivalent, account-based on a new platform, or a hybrid CBDC (distributed through third parties)._ Instead, this briefing proposes six design features that address specific problems facing the unbanked.

First, a CBDC designed for the unbanked should have no minimum balance requirements, as these requirements appear to be a barrier to many unbanked households in the FDIC survey._ This could be achieved in several ways, starting with the promotion of healthy competition in the marketplace. Stricter measures could include legislation or regulation to guarantee that there will always be one entity allowing consumers to hold CBDC without a minimum balance requirement, or to explicitly ban minimum balance requirements for all CBDC accounts. However this goal is achieved, setting no minimum balance requirements would be crucial to attracting unbanked consumers to CBDC accounts and having them maintain those accounts.

Second, consumers should be able to access CBDC and transact with it anytime, anywhere, and for little or no cost. This feature would mimic the convenience of cash in a digital form and address the problems of inconvenient bank hours and locations and high or unpredictable fees. Cash-equivalent designs are not the only methods for achieving this feature; multiple technology designs can achieve these types of transactions, such as real-time or peer-to-peer payments, on a variety of legacy and new payment rails. The more difficult task is ensuring that unbanked consumers pay negligible fees to make transactions using CBDC, as fees are often one way institutions make profits.

Third, a CBDC will have to balance transaction privacy for consumers while still complying with the Bank Secrecy Act and anti-money laundering regulation. While only 7.1 percent of unbanked households list “avoiding a bank gives more privacy” as their main reason for being unbanked, it is the third most-cited overall reason for being unbanked (36 percent). Moreover, unbanked consumers may be concerned about transaction privacy for additional reasons. Because firms that cater to unbanked households may not be able to recover their costs in the traditional ways, through fees, they may have to recover them in another way: selling data. As a result, a CBDC design for the unbanked should be focused on privacy and use caution in determining which parties can see, read, and maintain transaction data.

Fourth, endpoint access for a CBDC will have to entail more than a digital wallet via a smartphone app or webpage. Because unbanked households are less likely to have a smartphone or internet access than banked households, an assortment of endpoint solutions may be necessary to reach them, ranging from brick-and-mortar locations to stored-value cards to portable hardware devices.

Fifth, a CBDC should be at par with cash, and cash should be able to be converted into CBDC at little to no cost to the consumer. Just because a CBDC exists does not mean that cash businesses will immediately convert to it. Many unbanked consumers may still receive their income in cash. To avoid a potential predatory market for conversion, cash would need to be able to be converted to CBDC without cost.

Finally, financial institutions cannot be the only entities to support a CBDC. Many unbanked households are not interested in opening a bank account, and many unbanked consumers do not trust banks. To reach these unbanked households, public or private entities other than financial institutions will have to offer consumer interfaces or accounts for a CBDC. While these consumers may still be considered unbanked under the current definition, access to a CBDC account would allow them to be included in a digital financial system.

Conclusion

For a CBDC to achieve the goal of financial inclusion, or reaching all Americans, it must account for the needs of the unbanked with specific design features. Although these six features are by no means exhaustive solutions to the unbanked problem, a CBDC could alleviate some of these obvious concerns facing unbanked households. Whether some unbanked households would view a CBDC account any differently than a bank account remains to be seen. If some unbanked households see no distinction between the two, then a CBDC may not be able to reach those who wish to remain outside of the financial system. To overcome this challenge, policymakers may need to further consider whether to differentiate CBDC access from other digital products offered today and provide corresponding financial education.

Endnotes

-

1

While others have suggested that a CBDC may benefit the underserved by providing competition in the financial services market, this briefing focuses on the unbanked—those without a transaction account—and uses the term “account” to refer to a means of accessing a financial service (rather than describing an account-based CBDC). Whether or not a CBDC should be account-based is a separate discussion.

-

2

In 2016, the FDIC found that some consumers feel that “they don’t belong” in banks and that the culture of alternative financial services made them feel more comfortable (Rengert and Rhine 2016).

-

3

Previous research has shown that a cash-equivalent CBDC and an account-based CBDC would likely be more accessible than a hybrid CBDC that relies on financial accounts (Wong and Maniff 2020). This article does not presume that a hybrid model would be limited to financial accounts.

-

4

While addressing minimum balance requirements is crucial to CBDC adoption by the unbanked, one cannot overlook that a maximum cap on the funds allowed in a CBDC account may also affect adoption. If these caps are set too low, consumers may not be able to receive their salaries in CBDC accounts.

References

Barr, Michael S., Adrienne Harris, Lev Menand, and Wenqi Xu. 2020. “External LinkBuilding the Payment System of the Future: How Central Banks Can Improve Payments to Enhance Financial Inclusion.” Central Bank of the Future Project, working paper, July 31.

BIS (Bank for International Settlements). 2020. External LinkCentral Bank Digital Currencies: Foundational Principles and Core Features. Basel, Switzerland: Bank for International Settlements.

FDIC (Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation). 2020. External LinkHow America Banks: Household Use of Banking and Financial Services, 2019 FDIC Survey. FDIC, October.

George, Esther. 2020. “External LinkPondering Payments: Challenges of Reaching All Americans.” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Policy Perspectives, June 30.

Hayashi, Fumiko. 2016. “External LinkAccess to Electronic Payments Systems by Unbanked Consumers.” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Economic Review, vol. 101, no. 3, pp. 51–76.

Maniff, Jesse Leigh. 2020. “External LinkMotives Matter: Examining Potential Tension in Central Bank Digital Currency Designs.” Federal Reserve Bank of Kanas City, Payments System Research Briefing, July 1.

Maniff, Jesse Leigh, and W. Blake Marsh. 2017. “External LinkBanking on Distributed Ledger Technology: Can It Help Banks Address Financial Inclusion?” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Economic Review, vol. 102, no. 3, pp. 53–77.

Pew Charitable Trusts. 2016. External LinkWhat Do Consumers Without Bank Accounts Think About Mobile Payments? Pew Charitable Trusts, June.

Pew Health Group. 2010. External LinkUnbanked by Choice: A Look at How Low-Income Los Angeles Households Manage the Money They Earn. Pew Charitable Trusts, July.

Rengert, Kristopher M., and Sherrie L. W. Rhine. 2016. External LinkBank Efforts to Serve Unbanked and Underbanked Consumers: Qualitative Research. FDIC, May.

Toh, Ying Lei, and Thao Tran. 2020. “External LinkHow COVID-19 May Reshape the Digital Payments Landscape.” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Payments System Research Briefing, June.

Wong, Paul, and Jesse Leigh Maniff. 2020. “External LinkComparing Means of Payment: What Role for a Central Bank Digital Currency?” Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, FEDS Notes, August 13.

World Bank. 2018. “External LinkFinancial Inclusion: Overview.” October 2.

Jesse Leigh Maniff is a payments specialist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City or the Federal Reserve System.