While Oklahoma continues to employ more oil and gas workers than any state but Texas, Oklahoma’s energy sector has seen bigger job losses in recent years than any other oil and gas state. This edition of Oklahoma Economist examines the state’s energy production composition, drilling productivity, and employment mix to ascertain the structural reasons for this worrisome trend. It finds the state’s higher share of natural gas production, lagging productivity gains, and falling number of mining establishments and office workers all contributed to its outsized employment decline.

Mining employment fell more in Oklahoma than any other oil and gas state

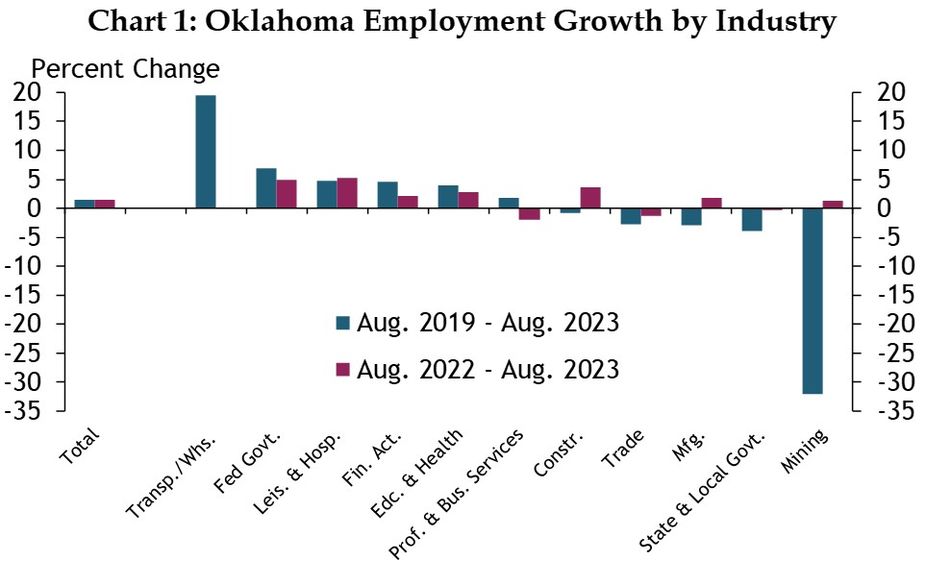

While most Oklahoma industries had only moderate changes in employment since 2019, two industries have seen much bigger transformations. The last edition of External LinkOklahoma Economist discussed the warehousing industry, which saw a nearly 20% increase in jobs in Oklahoma over the past four years. This edition addresses employment in the state’s large mining industry—almost completely comprised of oil and gas—which shed nearly a third of its jobs since August 2019 (Chart 1).

Notes: Professional and Business Services (Prof. & Bus. Services) includes Information. Trade includes Wholesale Trade and Retail Trade.

Source: BLS CES/Haver Analytics

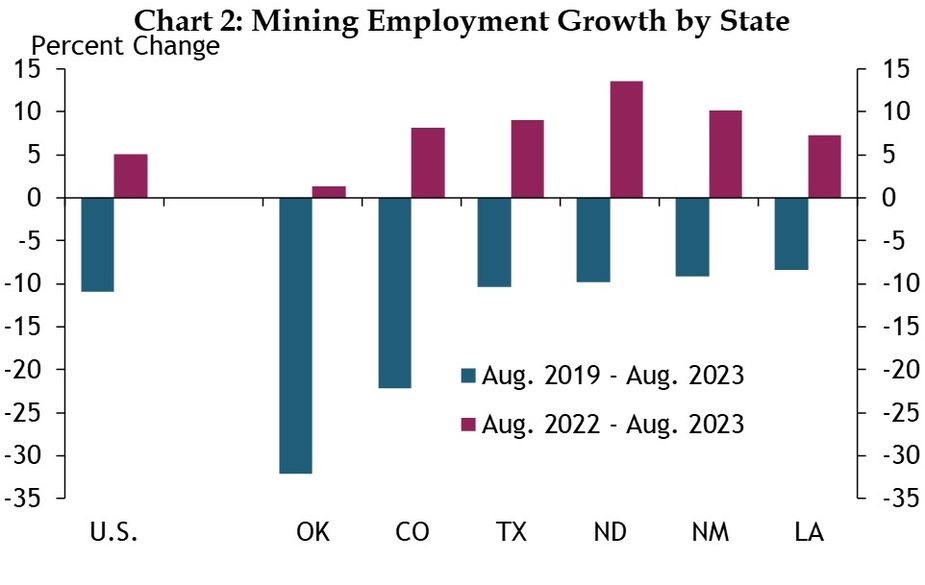

Not only is mining Oklahoma’s biggest employment laggard, but the state also experienced a significantly larger decline in jobs than any other state producing both oil and natural gas. Oklahoma’s 33% job loss since 2019 far exceeds the national average of 11% (Chart 2). Colorado, with a 22% decline, is the only other oil and gas state where mining sector jobs decreased more than the U.S. average.

Note: Mining employment includes Logging.

Source: BLS CES/Haver Analytics

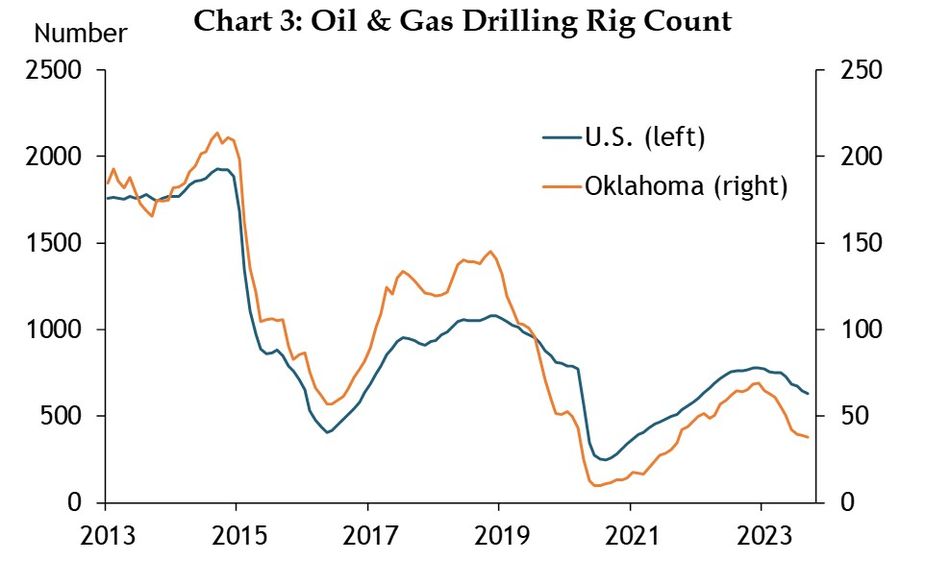

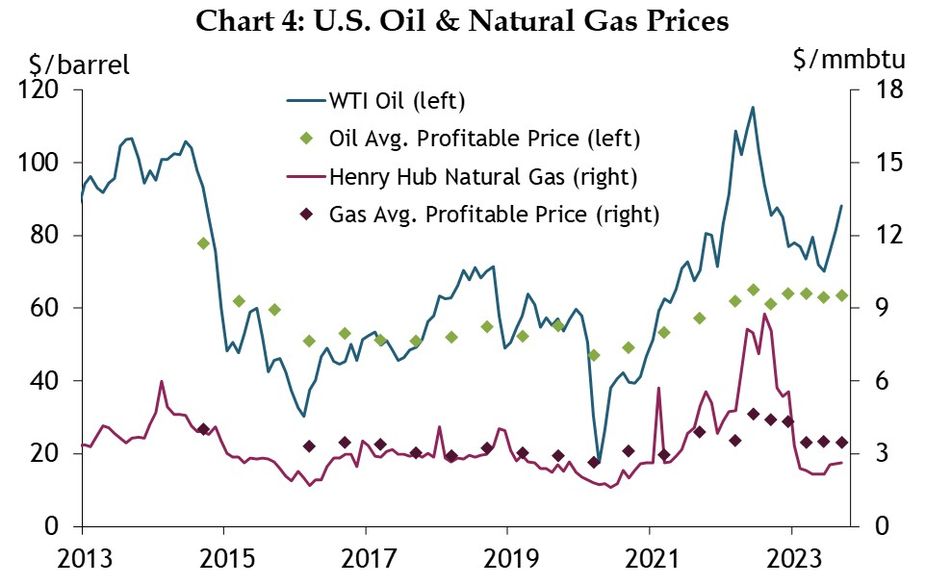

These job losses occurred during a time of declining mining activity both nationally and in Oklahoma (Chart 3). At the end of 2018, oil prices fell back near the level firms say is needed for profitability, according to the External LinkKC Fed’s quarterly Energy Survey (Chart 4). Soon after, natural gas prices decreased below firms’ average profitable price. Accordingly, the U.S. shed a quarter of its active oil and gas rigs in 2019, and Oklahoma’s count plummeted by nearly two-thirds, ending 2019 with only 51 rigs. These trends continued in 2020 as world petroleum demand weakened during the Covid-19 pandemic, and Saudia Arabia and Russia increased production in reaction to a price dispute (Wilkerson & Shupert 2020)_.

Source: Baker Hughes/Haver Analytics

Source: EIA/Haver Analytics, FRBKC Energy Survey

Oil and gas prices rebounded in 2021 as social and economic activity picked up following initial pandemic shutdowns. Then, they surged well above profitable levels following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022 as the U.S. began exporting more liquified natural gas to Europe (Wilkerson & Farha 2023)_. This lifted the nation’s rig count to 780 and Oklahoma’s to 69 by year’s end. This increase was ultimately short-lived as prices normalized in 2023 and rigs fell back to 631 in the U.S. and just 38 in Oklahoma by September.

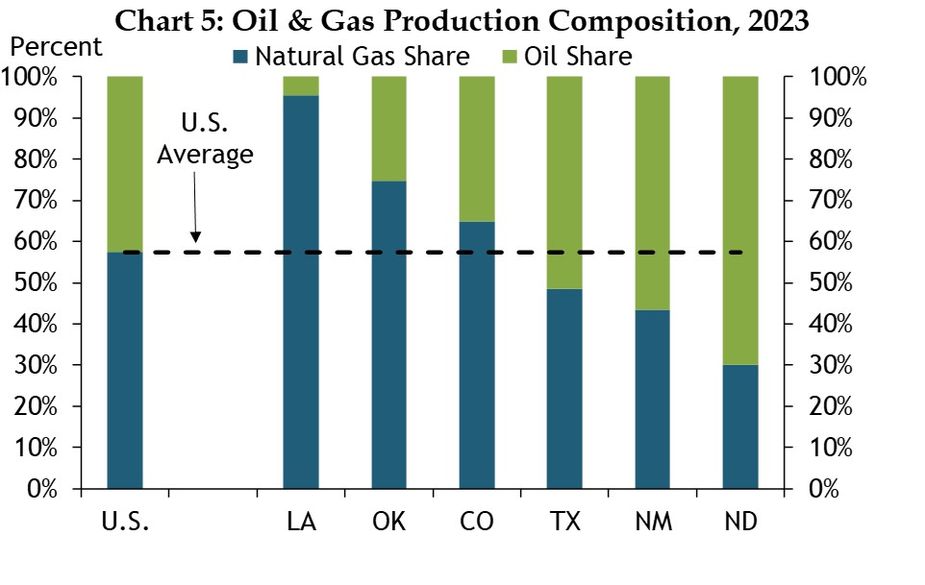

Falling profitability of natural gas

One explanation for Oklahoma’s larger relative decline in mining jobs could be its higher share of natural gas production. Apart from Louisiana, which is almost entirely a gas-producing state, Oklahoma has the highest share of gas production of any oil and gas state, at 75% (Chart 5). The only other state with a higher share of gas production than the national average is Colorado, which like Oklahoma had an outsized employment decline over the past four years (Chart 2). Although Louisiana also has an elevated share of gas production, a sizable portion of the drilling activity in the state is offshore, which may insulate it from large or rapid employment declines given the longer-term nature of offshore projects.

Notes: 2023 Production is calculated as an average of monthly production from January to July 2023. The composition is calculated by converting natural gas production from thousand cubic feet (MCF) to a barrel of oil equivalent (BOE), where 6 MCF = 1 BOE.

Source: EIA/Haver Analytics, authors’ calculations

A key contributing factor to gas-producing states’ employment declines is the low spot price for natural gas relative to oil for most of the past four years, including in 2023. While oil profit margins were squeezed earlier this year, they stayed above firms’ profitable price overall, with spot prices ranging from $70-88 a barrel in recent months while District firms’ profitable price remained around $63. However, natural gas prices plummeted to around $2.15-$2.62 per million Btu, well below the profitable price of $3.45 (Chart 4).

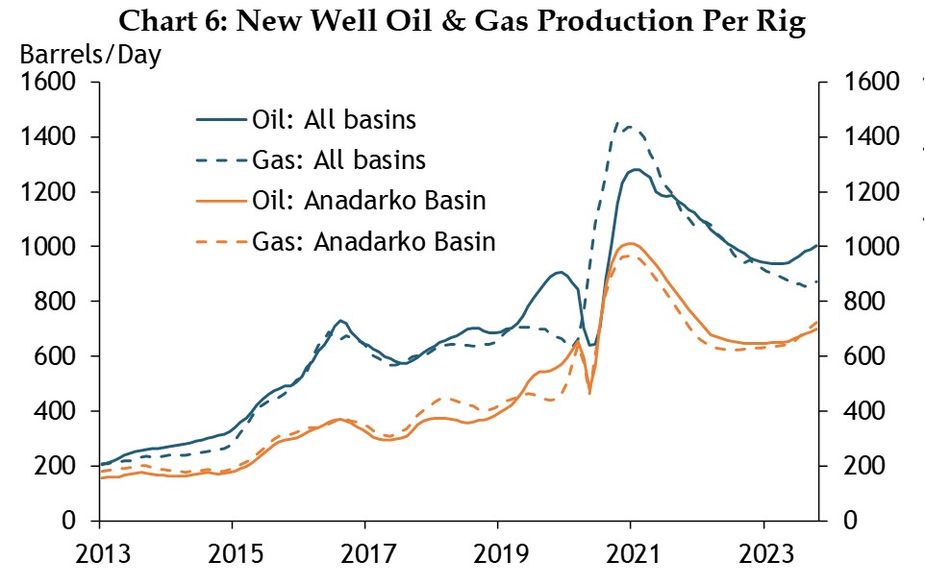

Lagging productivity gains

Lagging productivity gains present another possible reason for Oklahoma’s larger jobs decline. Over the past decade, new technology with increased below-ground efficiency caused a substantial rise in productivity in the oil and gas industry nationally (Brown et al. 2019)_ .This helps explain some of the overall national mining job losses over the past decade, as firms now need fewer rigs and workers to sustain production. The U.S. averaged production of about 200 barrels of oil and 200 equivalent barrels of oil of natural gas each day per rig in 2013 (Chart 6). In October 2023, oil and gas producers now average production of around 1,000 barrels of oil a day and about 870 equivalent barrels of oil of gas each day per rig.

Notes: Gas production is calculated by converting natural gas production from thousand cubic feet (MCF) to a barrel of oil equivalent (BOE), where 6 MCF = 1 BOE. New well production for all basins is calculated as an average across all basins weighted by rig count.

Source: EIA DPR/Haver Analytics, authors’ calculations

However, Oklahoma’s productivity gains have not been as strong. While new production per rig in the Anadarko Basin—a major basin located in central and western Oklahoma—nearly matched the national average in 2013, it now lags considerably, currently producing about 700 barrels a day of each oil and gas per rig. In addition, neither oil nor gas saw sizable productivity gains in the Anadarko over the past decade, unlike other major basins which each saw sizable gains in one fuel or the other. For example, the Appalachia and Haynesville basins greatly increased gas production per rig, while the Bakken, Eagle Ford, and Niobrara basins experienced large gains in oil production per rig_.

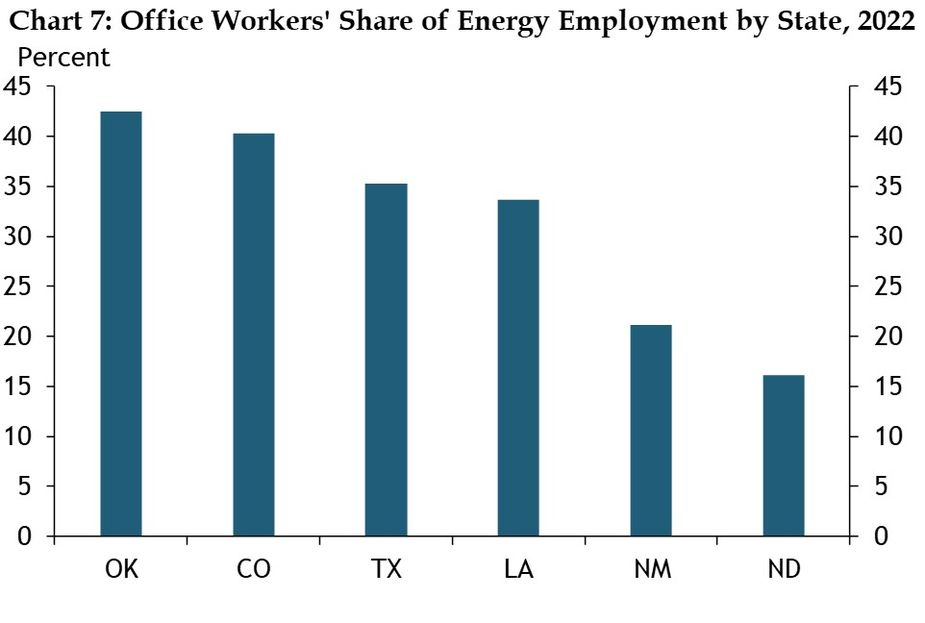

Larger losses in energy sector office jobs

Structural differences in Oklahoma’s employment composition can also potentially explain recent trends. For example, Oklahoma has the highest share of office workers employed in the oil and gas industry of any state, at 42%, suggesting it has more oil and gas headquarters or regional offices than most other drilling states (Chart 7)_. Thus, consolidation in the industry, which can be tracked via data on number of establishments, could have an outsized jobs impact in the state.

Source: BLS OEWS, authors’ calculations

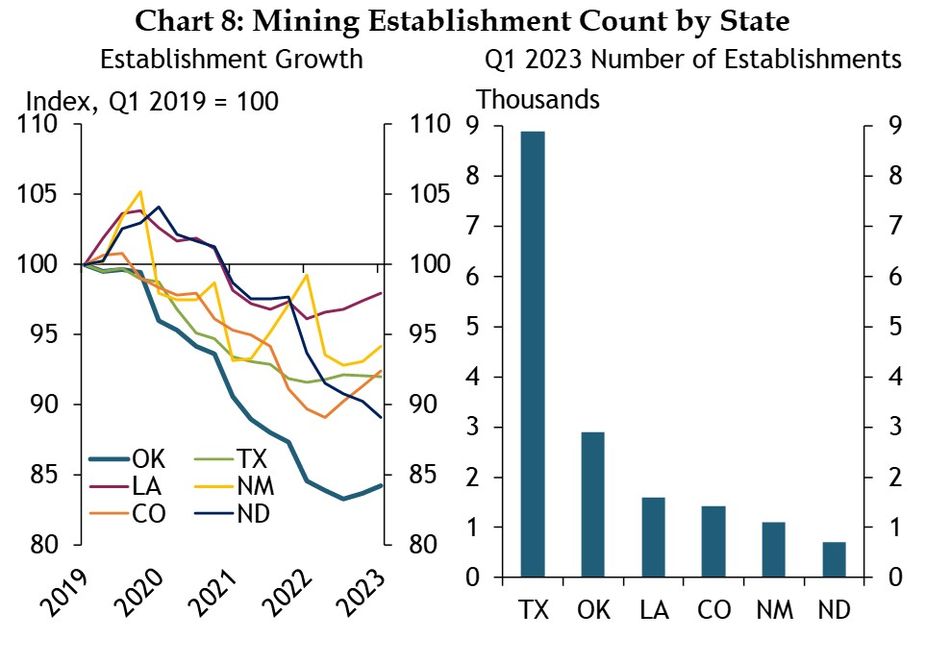

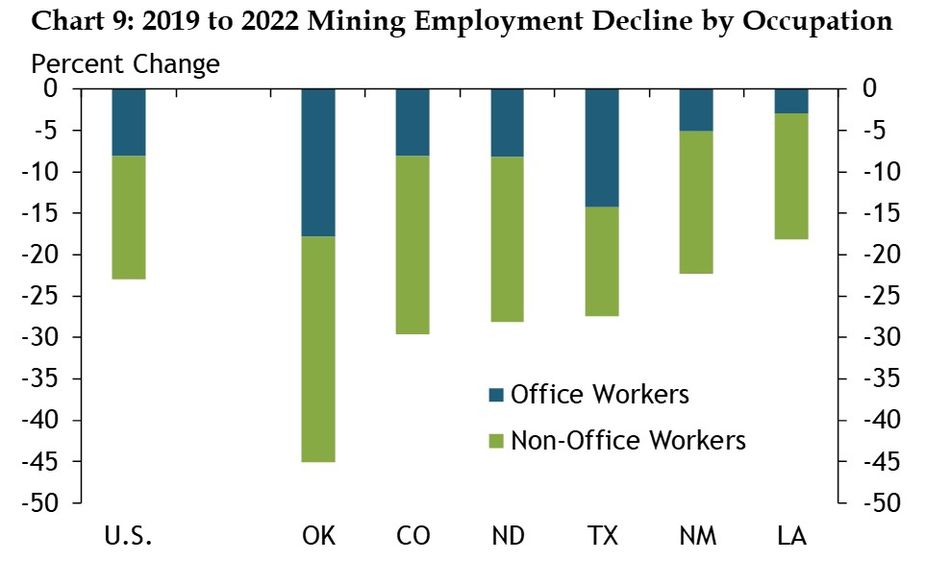

The Bureau of Labor Statistics defines an establishment as “the physical location of a certain economic activity.”_Thus, declines in the number of establishments can indicate a few things: consolidation of establishments within firms as economic activity falls, business failure, and/or corporate mergers and acquisitions. Each would cause some shedding of office jobs, particularly in areas where they are highly concentrated. Oklahoma experienced the largest decline in mining establishments of any state since 2019, although it still has the most mining establishments of any state other than Texas, at nearly 2,900 as of Q1 2023 (Chart 8). Not surprisingly, Oklahoma had the largest percentage drop in mining sector office jobs of any state (Chart 9). This is in addition to also having the biggest losses in non-office mining sector jobs, as drilling activity fell more in the state.

Source: BLS QCEW

Source: BLS OEWS

Summary and Conclusions

The oil and gas industry endured a turbulent few years, and Oklahoma was especially affected by downturns in the industry. Low natural gas prices and reduced drilling in 2019 spurred a drop in the state’s office employment as some firms slowed activity and consolidated. The pandemic exacerbated this trend, causing both office and non-office workers to lose jobs. Oklahoma’s higher share of gas production amid falling profitability, along with its slower productivity growth and larger number of headquarters and office workers, resulted in an outsized fall in state energy employment over the past four years. While the sector added jobs over the past year, these gains were smaller in Oklahoma than other oil and gas states, further widening the gap. Whether these trends can be reversed heading forward remains to be seen, but opportunities like new liquified natural gas markets for U.S. natural gas as well as technology enhancements within aging fields can sometimes alter the location of activity in the nation’s energy sector.

Endnotes

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

-

5

We define office workers as workers in the following occupational classifications (occupational code): Management (11), Business and Financial Operations (13), Computer and Mathematical (15), Architecture and Engineering (17), Life, Physical, and Social Science (19), Legal (23), Arts, Design, Entertainment, Sports, and Media (27), Protective Service (33), and Office and Administrative Support (43). We define non-office workers as workers in the following occupational classifications (occupational code): Construction and Extraction (47), Installation, Maintenance, and Repair (49), Production (51), and Transportation and Material Moving (53). Data are sourced from the Bureau of Labor Statistic’s Occupational Employment and Wage Statistics.

- 6