To say the least, 2020 has been an extremely difficult year for the Oklahoma and national economies. The economic downturn caused by the response of businesses, consumers and governments to the onset of COVID-19 has been unprecedented in speed and scale, pushing unemployment rates well into double digits in both the state and nation. Moreover, the plunge in oil prices that began even before the novel coronavirus reached U.S. shores, and the state’s still sizeable presence in that industry, has presented an additional challenge for Oklahoma’s economy. This edition of The Oklahoma Economist reviews how the state’s economy has been affected by these two shocks, and the path to recovery.

The COVID-19 shock

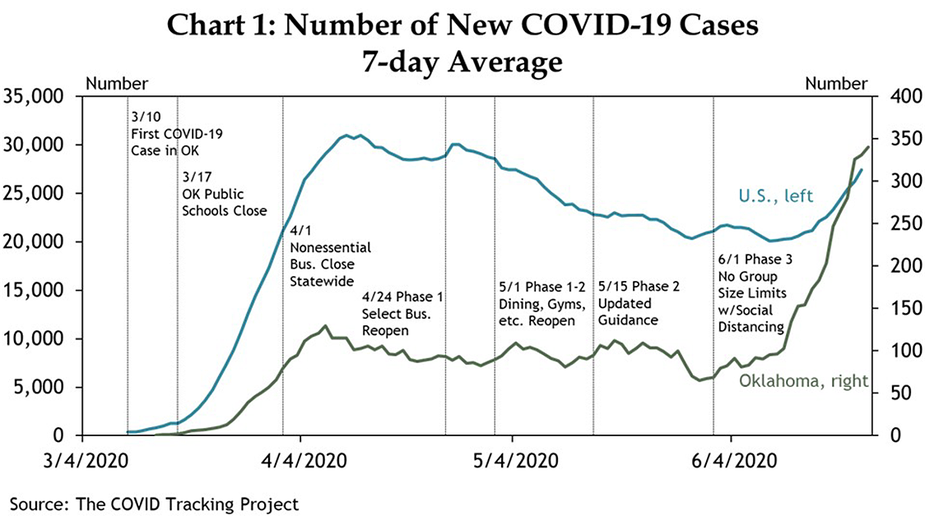

Oklahoma’s first COVID-19 case was reported March 10 (Chart 1). Within weeks, the average daily number of new cases approached 100, and all nonessential businesses across the state were closed April 1, as occurred in nearly all other states. As new cases per capita leveled off in April at well-below national averages and demand for hospital beds from COVID patients remained relatively low, businesses were steadily allowed to re-open from late April through early June. In mid-June, new daily cases in Oklahoma began to grow markedly again, creating some uncertainty about future potential effects on economic activity. Hospitalizations through the third week of June, however, had risen only slightly.

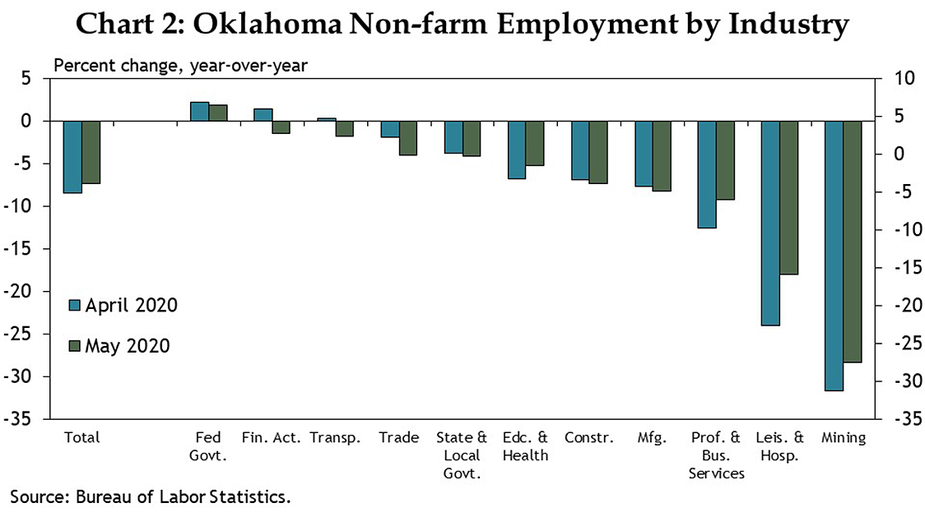

As businesses closed and consumer demand dropped in April and May, many firms furloughed or laid off workers, and employment in the state plummeted. Through May, the most recent state data available, jobs in Oklahoma were down over 7% from year-ago levels, slightly less than in the entire nation (Chart 2). Unemployment in the state, meanwhile, had risen to over 12%. By May, all industries in the state except for the federal government had shed jobs from a year ago. Job cuts were severe especially in the leisure and hospitality industry, falling more than 20% from year-ago levels in April before recovering slightly in May. That sector consists primarily of hotels and restaurants, which saw revenues drop sharply as businesses closed and consumers became increasingly cautious. But the sector with the biggest year-over-year job losses in April and May—over 25%—was mining, which in Oklahoma consists almost completely of oil and gas.

The oil price shock

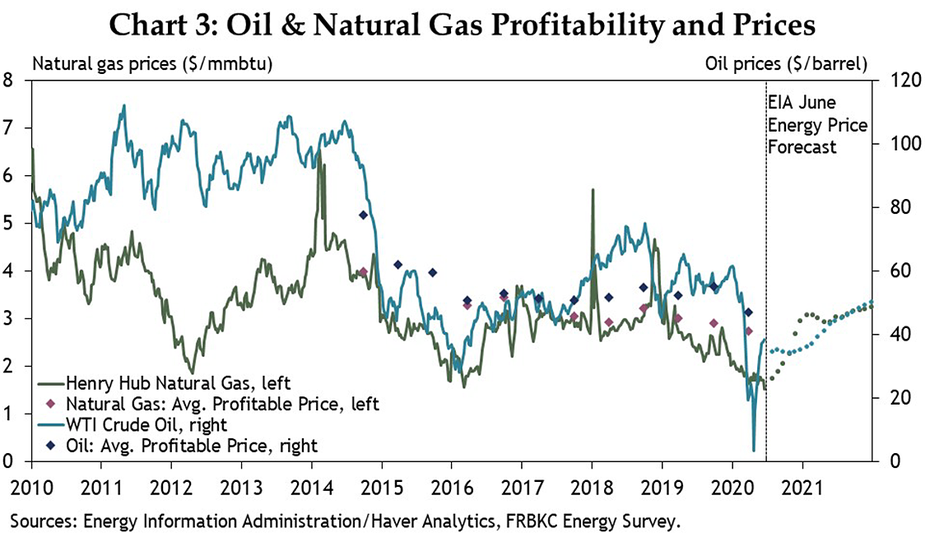

While every state in the country has had sizeable economic disruptions as a result of COVID-19, Oklahoma and other major energy-producing states have had the additional challenge of a collapse in oil prices (Chart 3). Oil already was on a steady price decline in early 2020, from over $60 a barrel at the beginning of the year to under $50 by early March. This was driven by slowing world petroleum demand and an oil price dispute between Saudi Arabia and Russia that led both countries to promise to increase production, pushing prices even lower. By mid-March, oil prices were below the average price that firms in the Federal Reserve’s Tenth District say is needed to be profitable for new drilling—around $45. Then as COVID-related travel concerns and restrictions severely curtailed gasoline and jet fuel demand, oil prices collapsed to under $20 by late April.

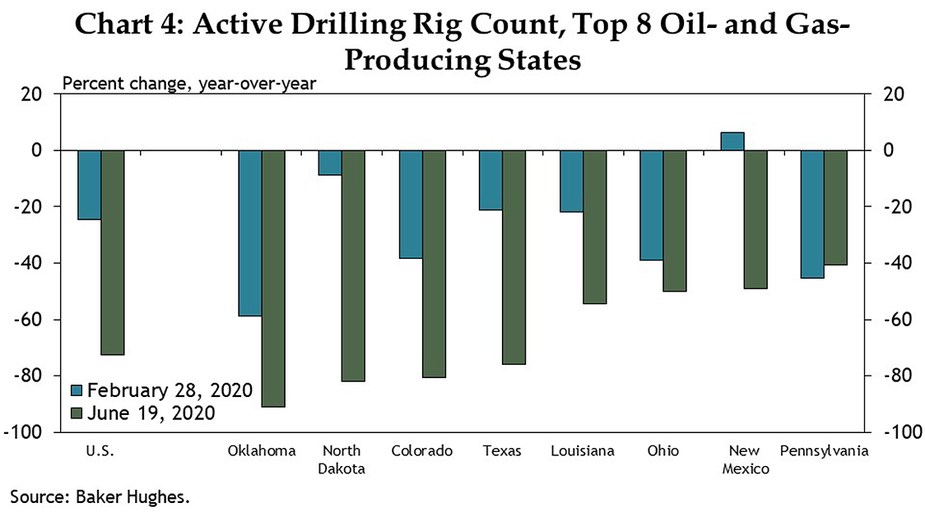

The sharp drop in oil prices led to a large reduction in energy activity in Oklahoma. New drilling in the state already had been falling well before March, as many firms had reallocated their activity to more productive fields in other states, especially the Permian Basin in southeastern New Mexico and west Texas. As of late February, Oklahoma’s rig count already was almost 60% below year-ago levels, compared with just 25% in the nation and with slight rig count growth in New Mexico (Chart 4). But by mid-June, Oklahoma’s count had dropped to more than 90% below previous-year levels, and employment in the state’s mining sector dropped from 50,400 jobs in May 2019 to just 36,100 in May 2020.

Recovering from COVID-19

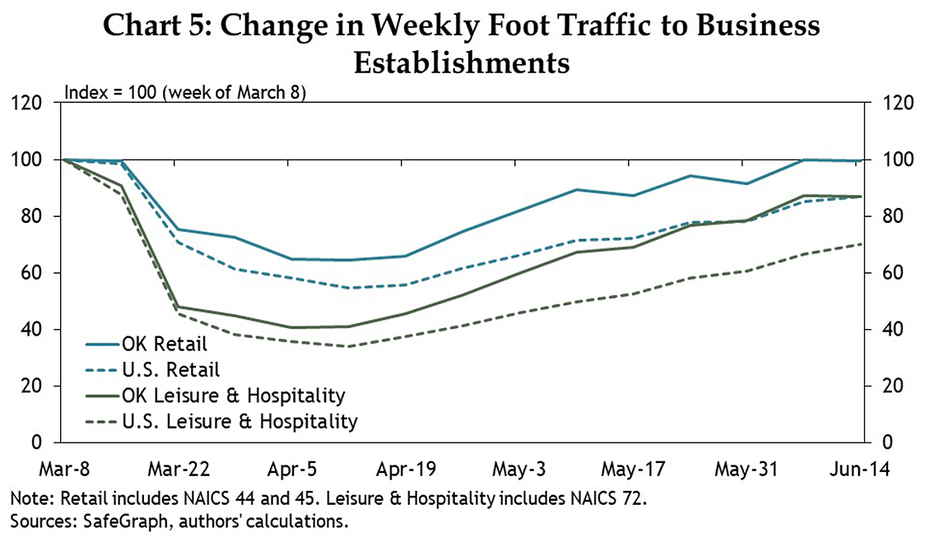

With the re-opening of many businesses and the cautious return of consumers in May and June, Oklahoma’s economy has begun to show signs of recovery, at a faster pace than in the nation. Foot traffic at retail establishments in Oklahoma in the first half of June returned to pre-COVID levels, after dropping by more than a third in early April (Chart 5). Such activity in the nation, according to SafeGraph, is still down more than 10 percent. Foot traffic at Oklahoma leisure and hospitality establishments has not fully rebounded from its sharper decrease but likewise was much closer to “normal” than in the nation. In addition, seated diners at restaurants accepting OpenTable reservations had returned to year-ago levels by the third week of June, while restaurant patrons in the nation as a whole remained 40% lower than last year.

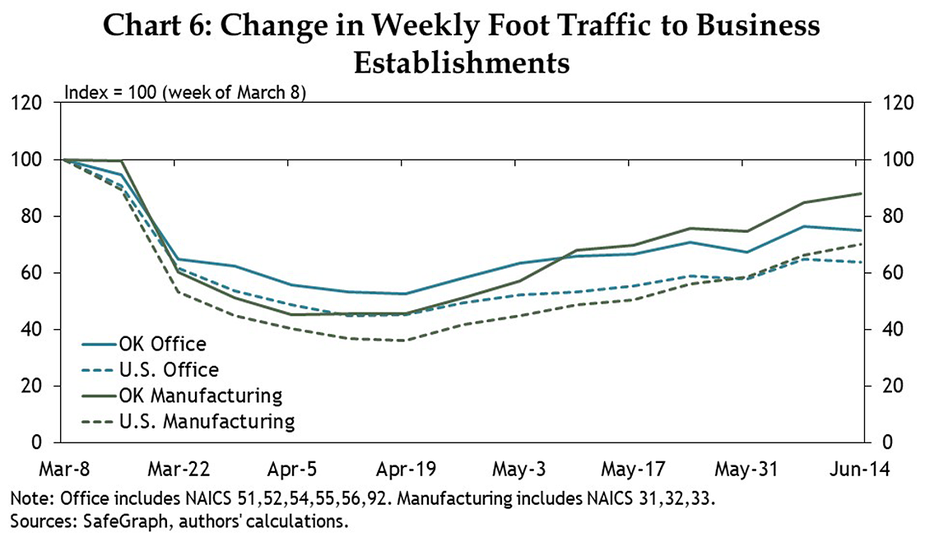

Foot traffic at manufacturing and office establishments likewise was much closer to pre-COVID levels in Oklahoma than in the nation by mid-June, as production lines restarted and remote workers returned to the office. However, manufacturing foot traffic still was more than 10% lower than in early March, and office traffic—consisting of firms in the professional and business services, finance and information sectors—remained about 25% lower than several months ago, as some firms were shuttered or remained in full or partial work-from-home modes (Chart 6).

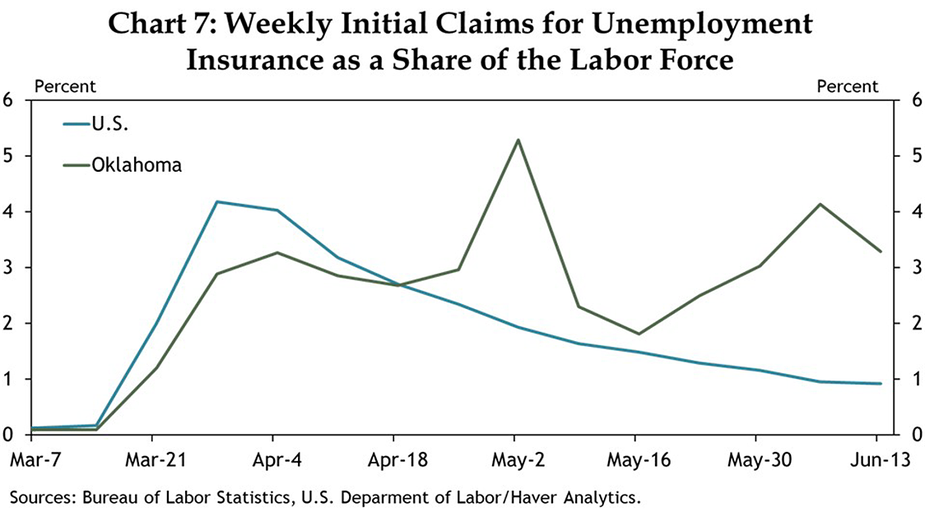

One key timely state indicator that had not yet begun to show much sign of recovery by mid-June was new claims for unemployment insurance. Through the second week of June, such claims in Oklahoma had not declined much from their peak in early May, and claims as a share of the state’s labor force have exceeded the nation since late April (Chart 7). The surge in new Oklahoma COVID cases in mid-June also has created some additional uncertainty about the future path of overall economic recovery, depending on how those trends evolve and how businesses, consumers and governments respond.

Recovering from the oil price bust

As overall economic activity in the nation and state has begun to pick up and as energy firms have severely curtailed production, oil prices have begun to recover. By the third week of June, prices had recovered to $40 a barrel, still slightly below average profitable drilling levels, but closer than in late April. However, the path back to that price has been painful for the industry. In addition to essentially halting new drilling and associated well completion activity, many firms took the drastic action in May and June of shutting in wells, or preventing oil from flowing to the surface. This was due to the rapid filling of oil storage and pipelines across the country, which forced local oil prices down into the single digits and even negative pricing for a time.

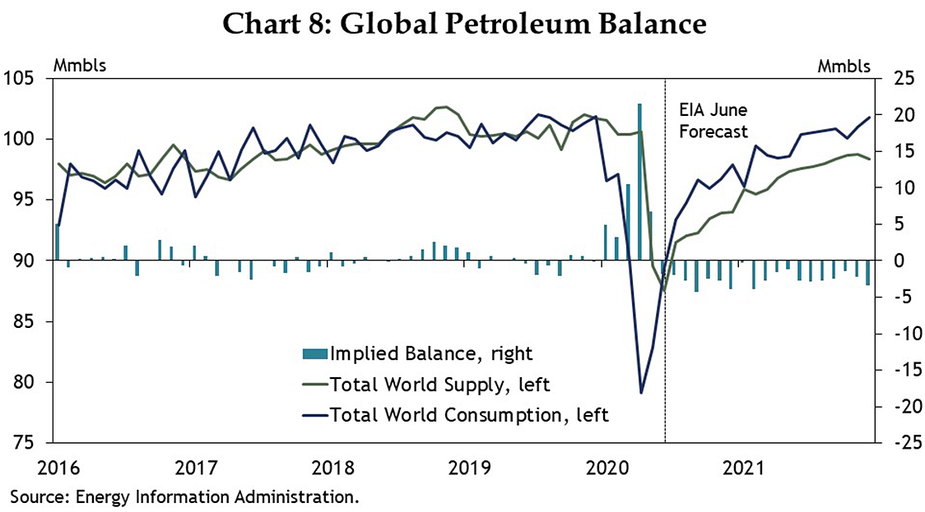

The result has been a rapid reduction in oil production in Oklahoma, the United States and even globally. Global petroleum supply has moved quickly closer to global demand levels, which were decimated by the shutdowns associated with COVID-19 (Chart 8). The U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) expects supply to now lag demand in coming quarters, helping to reduce the remaining elevated inventories and eventually push prices up to profitable levels by late 2021.

As with the overall economic recovery, however, considerable uncertainty remains about the future path of COVID-19 and how it will affect travel, creating some caution in the oil market. Moreover, the EIA does not expect world oil supply to rebound to close to pre-COVID levels through the end of 2021, suggesting any recovery in the sector could be sluggish. And even if the world oil market moves more quickly into balance, it seems unlikely that Oklahoma would be one of the early places to see a pickup in drilling since it was one of the places where activity was reduced first.

Summary

As in the nation, Oklahoma’s economy has been decimated by the effects of the spread of COVID-19. Unlike many other states, Oklahoma’s economy also has been hit hard by a severe drop in energy activity this year, associated with falling oil prices. In May and June, overall economic activity in the state slowly began to increase, with some measures returning to pre-crisis levels but some remaining stubbornly below. Oil prices also have recovered considerably as world oil supply declines toward lower demand levels. However, the number of jobless Oklahomans remains very high, the number of new COVID cases in the state has recently surged, and any rebound in U.S. energy activity does not seem as likely to occur in Oklahoma as other places. As such, while economic conditions in the state have improved considerably from the depths of the crisis, there still is a long way to go and risks remain.