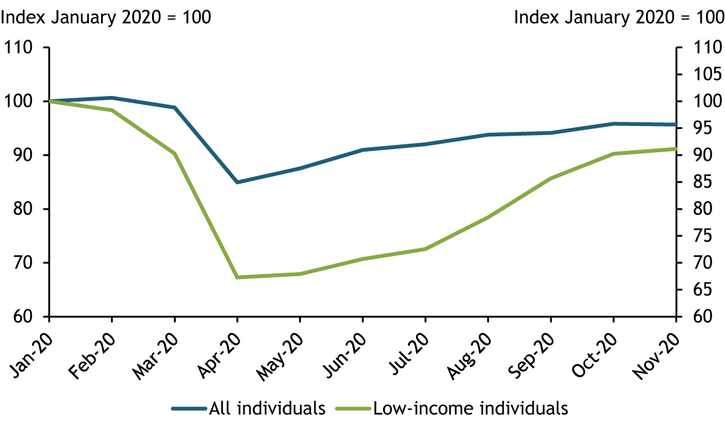

The COVID-19 pandemic has led to substantial declines in employment in the United States, especially among low-income individuals (those with family income below $40,000)._ Chart 1 shows that employment among low-income individuals fell by 31.6 percent between February and April, compared with a decline of 15.6 percent in the overall population. This decline corresponded to a loss of 10.4 million jobs (from 32.7 million to 22.3 million) among low-income individuals. Employment among low-income workers began recovering in May. But as of November, their employment level remained 7.3 percent below its pre-pandemic level.

Chart 1: Employment among Low-Income Individuals Fell Sharply in March

Sources: Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) and authors’ calculations.

Low-income individuals tend to lack savings and have limited access to mainstream credit, so they may be especially prone to financial difficulties after employment disruptions. According to the 2019 Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking (SHED), only 27 percent of low-income individuals have sufficient savings to cover three months of expenses (compared with almost 53 percent of the overall population). The survey also found that low-income individuals are more likely to experience difficulties obtaining mainstream credit such as bank loans and credit cards: 51 percent of low-income individuals have had their credit applications denied or have been granted less credit than requested, compared with 31 percent of the overall population.

Perhaps as a result, many low-income individuals turn to high-cost loans from alternative financial services (AFS) providers, such as payday and title lenders and pawnshops, to meet their financial needs. Nearly 10 percent of low-income individuals use alternative financial services compared with only 5 percent of the overall population. Because low-income individuals turn to AFS when they are unable to access credit through mainstream channels, an increase in their use of AFS loans may indicate they are facing greater financial distress.

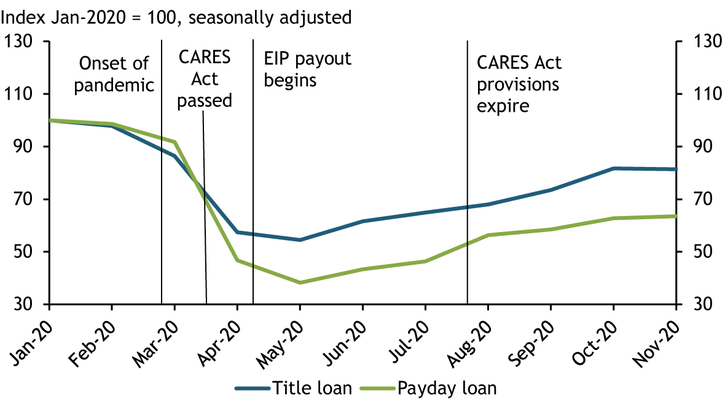

Detailed lending data from AFS are not publicly available, but evidence from search engine traffic suggests that fewer low-income individuals have taken out AFS loans since the start of the pandemic. Chart 2 shows that seasonally adjusted Google search interest in the terms “payday loan” and “title loan” fell substantially in March and April, suggesting fewer individuals were pursuing these loans. Despite a slight upward trend since May, search interest in AFS loans has remained below pre-pandemic levels.

Chart 2: Google Searches for “Payday Loan” and “Title Loan” Remain below Pre-Pandemic Levels

Sources: Google Trends and authors’ calculations.

Similarly, pawnshops, which typically increase their lending during recessions, have experienced a decline in pawn loan demand since the onset of the pandemic. The National Pawnbrokers Association reported that lending business at pawnshops across the country has decreased on average by 40 to 50 percent this year (Grant 2020). At the same time, loan redemptions have increased, suggesting an improvement in pawn loan users’ finances (Stewart 2020).

The absence of these typical signs of increased financial distress among low-income individuals, despite their relatively high job loss rates, is likely attributable to government pandemic relief efforts. Some federal, state, and local relief efforts have helped low-income individuals by temporarily reducing their financial obligations. For example, the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act that Congress passed on March 27 provided individuals eviction protection through July 2020. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issued an order on September 4 halting all evictions through December 31, 2020, with the goal of preventing the spread of COVID-19. And many state governments have placed moratoriums on utility shutoffs, potentially preventing low-income individuals from taking out costly AFS loans to pay their monthly bills.

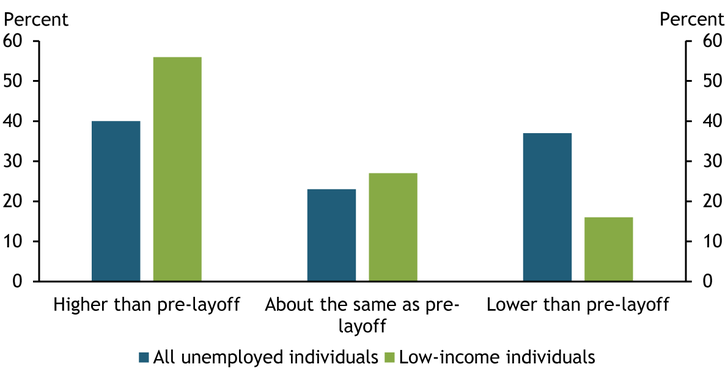

Other pandemic relief efforts have helped low-income individuals through direct payments. Under the CARES Act, individuals whose income fell below certain thresholds were eligible to receive Economic Impact Payments (EIP) of up to $1,200 per adult and an additional $500 per child in the household._ A low-income household of four (two adults and two children) making less than $40,000 annually would have received $3,400 in EIP, more than the household’s average monthly income. The additional $600 per week in unemployment insurance benefits provided by the CARES Act may also have raised the income of those laid off during the pandemic. Chart 3 compares unemployment benefits with pre-layoff wages for low-income individuals as well as the overall population using data from the July 2020 SHED supplement. The first pair of bars shows that 56 percent of low-income individuals who received unemployment insurance benefits reported that these benefits exceeded their pre-layoff wages, compared with 40 percent of the overall unemployed population.

Chart 3: Unemployment Insurance Benefits Exceeded Wages for Many Low-Income Individuals

Sources: Federal Reserve Board and authors’ calculations.

Although earlier pandemic relief efforts appear to have prevented some low-income individuals from experiencing greater financial distress thus far, the effects are beginning to wear off. Some of the economic aid from the CARES Act, including the enhanced unemployment benefits of $600 per week, ended in late July, and households are likely to have run out of any savings they may have set aside from these benefits by now._ Moreover, job losses and furloughs among low-income individuals could rise in the coming months, as a resurgence in the virus further weighs on small businesses and contact-intensive occupations. In December, small business closures reached a six-month high, and initial unemployment claims—a proxy for layoffs—began rising after months of declines. As the cold weather renders the use of outdoor spaces for business operations unfeasible in many parts of the United States, many more businesses—particularly those in leisure and hospitality industries—may be forced to close at least temporarily and lay off or furlough workers. These job losses and furloughs will likely disproportionately affect low-income workers, who are over 50 percent more likely to be employed in the leisure and hospitality industries than the average worker._

Although the new stimulus package passed in late December will offer some relief for low-income individuals, it may not be sufficient to help these individuals avert economic hardship and avoid the use of AFS loans. Under the new package, eligible individuals will receive $600 in direct payments and $300 in weekly supplemental unemployment benefits—half of what they received under the CARES Act.5 For many individuals, this aid is likely to fall short of the debt they have accumulated since the onset of the pandemic. A study by the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia estimates that 1.3 million rental households (3.9 million individuals) will owe on average $5,400 in back rent by December 2020 (Reed and Divringi 2020). Although the stimulus package extends the eviction moratorium to January 31, 2021, by the time it expires, the average amount owed will likely be even higher. Moreover, the new supplemental unemployment benefits are set to expire in mid-March, possibly before COVID-19 vaccines are widely distributed. A hefty rent bill and a loss of unemployment benefits may cause these individuals to experience greater economic hardship—and they may once again resort to costly AFS loans to meet their payment obligations.

Endnotes

-

1

We follow the Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking in defining low-income individuals as those with annual household income under $40,000.

-

2

Income thresholds and other eligibility conditions for the EIP can be found on the Internal Revenue Service’s website.

-

3

One study found that individuals who had received the expanded unemployment benefits spent, on average, two-thirds of the savings they had accumulated from March through July in the month of August, when the additional benefits ended (Farrell and others 2020).

-

4

Based on authors’ calculations using data from the Current Population Survey.

-

5

At the time of this publication, the House of Representatives has voted to increase the stimulus check to $2000, but the Senate has yet to vote on the issue.

References

Farrell, Diana, Peter Ganong, Fiona Greig, Max Liebeskind, Pascal Noel, Daniel Sullivan, and Joseph Vavra. 2020. External LinkThe Unemployment Benefit Boost: Initial Trends in Spending and Saving When the $600 Supplement Ended. JP Morgan Chase & Co. Institute, Policy Brief, October.

Grant, Tim. 2020. “External LinkPawn Shops Fall on Hard Times as Products Dry Up and Customers Are Flush with Cash.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, August 14.

Reed, Davin, and Eileen Divringi. 2020. External LinkHousehold Rental Debt during COVID-19. Philadelphia: Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia.

Stewart, Emily. 2020. “External LinkIt’s Easy to Assume Pawnshops Are Doing Great in the Pandemic. It’s Also Wrong.” Vox, November 30.

Ying Lei Toh is an economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City. Thao Tran is a research associate at the bank. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City or the Federal Reserve System.