Bank regulatory and supervisory requirements increased sharply in response to the significant monetary and social costs incurred during the Global Financial Crisis. Since that crisis, however, several policymakers have questioned whether the higher compliance costs of these more stringent requirements could outweigh their safety and soundness benefits, especially for smaller and less complex banks (Bessent 2025b; Gould 2025b). Accordingly, some policymakers have proposed additional tailoring of bank supervision and regulation according to characteristics such as size, complexity, business model, and risk (Bessent 2025a; Bowman 2025; Gould 2025a; Hill 2025). Underlying the tailoring philosophy is the idea that systemically important banks—that is, banks whose failures would result in high social costs and taxpayer liabilities—should bear the higher costs of additional supervision and regulation, while non-systemic banks should be subject to a less burdensome, and lower cost, oversight program. Advocates of this approach argue that tailored requirements will better enable banks to serve their customers’ needs and drive economic growth while still ensuring financial stability.

While the idea of tailoring policy to individual banks is straightforward, implementing it in practice can present several thorny decisions. Most critically, regulators must distinguish between banks that pose systemic risk and those that do not. They must also decide which banks are low risk or non-complex alongside any other characteristics deemed significant. These classifications are not necessarily clearcut._ Some banks pose no or limited systemic risks, while others, namely very large global banks, can pose significant systemic risks in the event of failure, and determining these cutoffs can be subjective.

Both research and regulation commonly classify banks for tailoring purposes based on asset size because systemic risk and potential social costs associated with failure generally increase with asset holdings (Kandrac and Marsh 2025). Small bank failures, for instance, present less risk to the FDIC’s deposit insurance fund and little risk to taxpayers more broadly. Conversely, large bank failures are more likely to require federal bailouts or other government support measures to stem funding market contagion or sharp declines in credit availability to the macroeconomy.

Smaller banks also tend to have other desirable characteristics that merit a more modest supervisory and regulatory approach. Smaller banks tend to operate less complex, deposit-based lending businesses, for example, which are less likely to require the intensive supervisory programs needed for banks that operate complex trading desks or conduct foreign lending operations. Similarly, small banks tend to operate more localized branch networks that are easier to monitor and manage than extensive nationwide or global operations.

However, tailoring supervisory and regulatory guidance using simple asset thresholds has several drawbacks. First, size may not be a good proxy for risk. In fact, unconditional failure probabilities may be higher for smaller banks due to various forms of concentration risk. For example, small banks’ more localized branch networks can expose them to regional asset quality and funding shocks. Indeed, many small banks failed in the 1980s when a sharp decline in oil prices increased unemployment and reduced housing prices in the energy-producing southwestern United States (FDIC 1997). In addition, smaller banks’ lending concentrations, particularly in commercial real estate and small business lending, can expose them to sectoral shocks (Marsh and Sengupta 2017). Moreover, some small banks operate niche business models or engage in certain non-traditional or novel activities that may require additional supervision to appropriately manage risks. Second, size is not always a good indicator for complexity, particularly for medium sized banks. Larger banks that fall outside typical asset threshold levels can operate traditional banking models that do not require sophisticated supervision, similar to their smaller peers. For these reasons, asset size is an imperfect indicator of bank risk and complexity that can produce imperfect bank classifications for tailoring purposes.

An alternative to classifying banks based on asset size is to more precisely define banks according to specific characteristics. This approach requires identifying universally agreed upon criteria that define a group of banks for supervisory and regulatory purposes._ One advantage of more precise definitions is that they allow policymakers to screen out riskier and non-traditional banks that may require additional supervision and regulation but would be classified as non-complex based on a simple asset threshold. Similarly, precise definitions can allow policymakers to reduce regulatory burden for larger banks that operate traditional and less complex business models. In other words, precise definitions address the main drawbacks of an asset-based approach by guaranteeing banks are classified as desired.

However, more precise approaches have disadvantages as well. First, greater precision will likely increase regulatory complexity and opaqueness. In the extreme, banks and investors may not understand, or disagree with, the assigned classifications, or the methodology may be difficult to communicate to interested parties. Second, increased regulatory complexity or a high burden of proof for banks to demonstrate they should be subject to fewer regulatory requirements can increase costs for both agency staff and the banks themselves. Very specific definitions, for example, may require new data collections or additional supervisory conversations to determine the correct classification. Additionally, some determinations may require subjective assessments that are not easily measured, prompting disagreements between bankers and their supervisors about their classifications. Ultimately, after accounting for these practical considerations, a precise definitional approach may be more burdensome to apply than asset thresholds without substantially improving the accuracy of classifications.

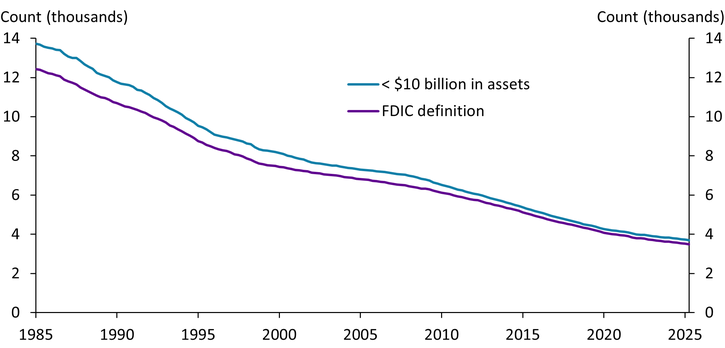

A key question is how much do the classification results vary when using asset-based thresholds versus more precise definitions? Although this answer ultimately depends on the criteria used, Chart 1 illustrates one example by comparing two commonly used community bank definitions._ Community banks tend to be small, traditional banks that face typical credit and liquidity risks, making them good candidates for tailored oversight that requires a clear regulatory classification (Kandrac and Marsh 2025). Researchers and regulators commonly use $10 billion in total assets as a benchmark to define community banks. Alternatively, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) has proposed a research definition for community banks that uses publicly available data to classify banks based on characteristics such as asset size, geographic and portfolio concentration, and business model.

Chart 1: Community bank charter counts are similar using either classification method

Note: Chart shows the number of banking charters as defined by the Federal Reserve Board’s H.8 release and those classified as community banking organizations by the FDIC.

Sources: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System and FDIC.

Chart 1 shows that in the 1980s, when banks were generally smaller, the two definitions diverged by about 2,000 bank charters. This divergence is predominately due to the relative size of the $10 billion threshold compared with the typical bank’s assets at that time. As the banking industry has grown nominally and consolidated through mergers, though, banks tend to more cleanly fall into both community bank definitions. As a result, the two definitions have converged in recent years, with a 204 bank difference mostly accounted for by a few specialty banks excluded by the FDIC’s criteria.

Overall, supervisory and regulatory tailoring has wide support among policymakers, academics, and banking industry practitioners and analysts. However, the design criteria must be carefully considered due to both the potential financial stability implications and the costs that may be incurred by banks and their regulatory agencies. While asset thresholds have clear drawbacks, they may best balance these trade-offs given the high correlations between asset size and other desirable characteristics in a tailored oversight framework.

Endnotes

-

1

Currently, large and regional banks are divided into five risk-based categories for regulatory purposes. For an overview of these categories, see SIFMA (2023).

-

2

There are an endless number of possible characteristics that one could consider for the purposes of tailoring; however, commonly cited qualities are size, business model, complexity, and risk. For a review of some specific implementations and proposals, see CRS (2017).

-

3

For an example of a complex tailoring classification applied to very large, foreign operating banks, see the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision’s GSIB assessment methodology on the External LinkBank for International Settlements website.

References

Bessent, Scott. 2025a. “External LinkRemarks by Secretary of the Treasury Scott Bessent Before the Fed Community Bank Conference.” October 9.

———. 2025b. “External LinkTreasury Secretary Scott Bessent Remarks at the Financial Stability Oversight Council.” September 10.

Bowman, Michelle W. 2025. “External LinkTaking a Fresh Look at Supervision and Regulation.” Speech at the Georgetown University McDonough School of Business Psaros Center for Financial Markets and Policy, June 6.

CRS (Congressional Research Service). 2017. “External LinkTailoring Bank Regulations: Differences in Bank Size, Activities, and Capital Levels.” December 21.

FDIC (Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation). 1997. “External LinkHistory of the Eighties: An Examination of the Banking Crises of the 1980s and Early 1990s.” December.

Gould, Jonathan. 2025a. “External LinkComptroller Issues Statement on Areas of Focus as FDIC Board Member.” October 7.

———. 2025b. “External LinkRemarks of Jonathan V. Gould.” Speech at the Financial Stability Oversight Council, September 10.

Hill, Travis. 2025. “External LinkView from the FDIC: Update on Key Policy Issues.” Speech at the American Bankers Association Washington Summit, April 8.

Kandrac, John, and W. Blake Marsh. 2025. “External LinkCommunity Banking Organizations,” in Allen N. Berger, Phillip Molyneaux, and John O. S. Wilson, eds., Oxford Handbook of Banking, 4th Edition, Oxford University Press.

Marsh, W. Blake, and Rajdeep Sengupta. 2017. “External LinkCompetition and Bank Fragility.” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Research Working Paper no. 17-06, June.

Milhorn, Brandon. 2025. “External LinkRemarks by CSBS President and CEO Brandon Milhorn at the 2025 Community Banking Research Conference.” October 7.

SIFMA (Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association). 2023. “External LinkUnderstanding the Current Regulatory Capital Requirements Applicable to U.S. Banks.” February 6.

W. Blake Marsh is a senior economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City or the Federal Reserve System.