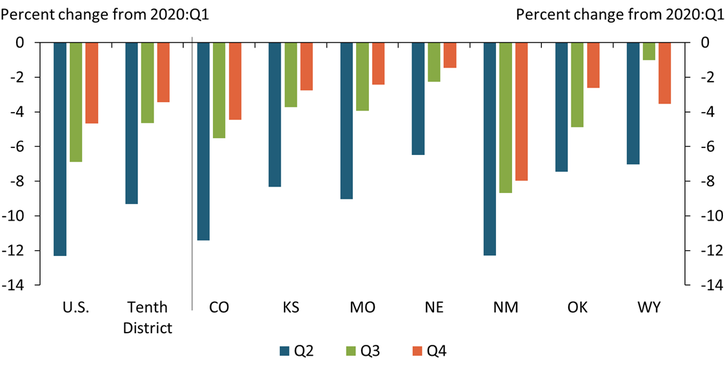

In March 2020, the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in severe job losses across the country and in all states within the Tenth Federal Reserve District. Public health directives, business restrictions, and consumer preferences for limited personal contact influenced most industries in the country to some degree. The blue bars in Chart 1 show that each state within the Tenth District had experienced job losses of at least 6 percent by 2020:Q2, with especially steep losses in Colorado and New Mexico. One explanation for these losses is a relatively high share of employment in industries hit hardest by early economic restrictions. For example, 12 percent of pre-pandemic employment in Colorado was in the accommodation and food service industry; nearly 40 percent of job losses in Colorado in 2020:Q2 came from this industry.

Chart 1: Job Losses in the Tenth District Were Severe, and the Pace of Recovery Has Been Uneven

Note: The Tenth Federal Reserve District includes the states of Colorado, Kansas, Nebraska, Oklahoma, Wyoming, the western third of Missouri, and the northern half of New Mexico.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).

As the year progressed, many of the jobs lost were recovered, though the strength of the recovery varied across states. For example, the green and orange bars show that three-quarters of lost jobs in Nebraska had recovered by 2020:Q4 compared with just over one-third of jobs lost in New Mexico. In Wyoming, the number of jobs actually declined from 2020:Q3 to 2020:Q4.

In response to sudden and substantial disruptions in the labor market, the federal government supplemented state unemployment insurance programs through the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act. The CARES Act provided an additional $600 per week to unemployed people throughout much of the second quarter of 2020. In addition, the CARES Act extended the duration of unemployment benefits and expanded coverage to those not typically eligible, such as self-employed individuals and independent contractors.

These enhancements greatly mitigated income lost from wages following severe job losses in the first half of 2020. I calculate that between 60 and 87 percent of individuals across the seven Tenth Federal Reserve District states who lost jobs in 2020:Q2 had their previous wages fully replaced or exceeded by state unemployment insurance benefits and federal supplements._ Although the $600 supplement expired in 2020:Q3, executive action provided a $300 per week supplement from FEMA for much of the quarter. Even with the weekly supplement halved, I calculate that between 10 and 47 percent of unemployed individuals across the Tenth District states in 2020:Q3 had their wages at least fully replaced while the funds were available. Federal support to state unemployment insurance dropped to zero in 2020:Q4, and additional federal supplements were not reinstated until the end of the year.

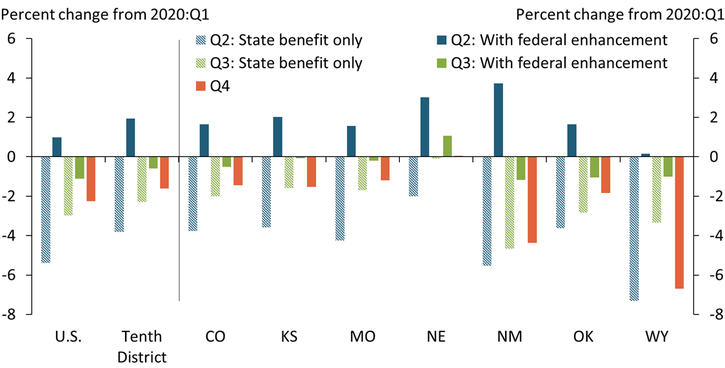

Federal enhancements supported income in all states. To further explore how expanded unemployment insurance benefits supported income, I assess how total income—here, the sum of weekly wages and unemployment benefits—in each state evolved relative to 2020:Q1 and then compare these state incomes to those that would have prevailed without federal supplements to state unemployment insurance._ Comparing the striped bars to the solid bars in Chart 2 shows that incomes in both the United States and Tenth District would have been substantially lower throughout 2020 without federal enhancements. In the Tenth District, for example, total income in 2020:Q2 would have been 4 percent lower than its 2020:Q1 level without federal enhancements such as the $600 weekly supplement. With the enhancements, total income in 2020:Q2 was actually 2 percent higher than in 2020:Q1. Indeed, the solid blue bars show that CARES Act supplements resulted in 2020:Q2 income gains in all states, with total income increasing by as much as 3.7 percent in New Mexico.

Chart 2: Federal Support to Unemployment Insurance Boosted Income in the Tenth District

Sources: BLS, Nolo Legal Encyclopedia, and author’s calculations.

Federal enhancements to unemployment insurance continued to mitigate income from lost wages in 2020:Q3, albeit at lower levels than in 2020:Q2. In some states, such as Nebraska, income from wages and state unemployment benefits alone (striped green bar) returned almost entirely to 2020:Q1 levels. With the $300 weekly federal enhancements, 2020:Q3 income from wages and unemployment benefits in Nebraska exceeded 2020:Q1 levels, while total income in other states in the region were near pre-pandemic levels.

When federal enhancements to unemployment insurance ended in 2020:Q4, total income declined relative to 2020:Q1 levels in all states, though to varying degrees (solid orange bars). Only in Nebraska did income from wage and unemployment benefits nearly match pre-pandemic levels. In contrast, New Mexico and Wyoming saw declines of more than 4 and 6 percent, respectively.

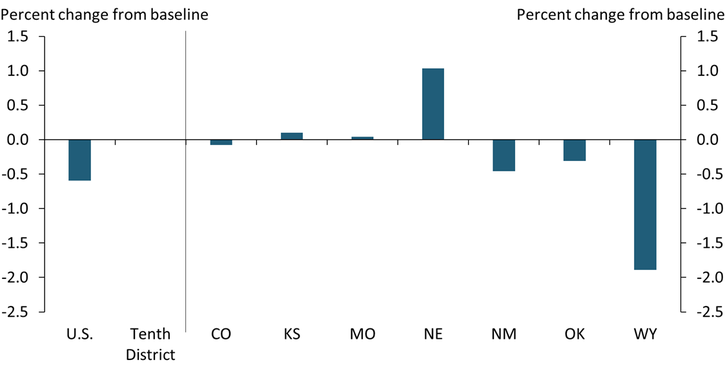

To further test how federal enhancements to unemployment insurance supported incomes, I next investigate how total incomes in each state in 2020 compare to what might have been expected absent the pandemic. Chart 3 shows how total income from unemployment benefits, federal enhancements, and wages in 2020 compares with a hypothetical scenario in which employment and wages observed in 2020:Q1 remained constant all year. I calculate total income by adding wages earned in the first quarter with changes in total quarterly wages and unemployment benefits—including federal supplements, when in effect—for the second, third, and fourth quarters relative to the first quarter (corresponding to the solid bars in Chart 2).

Chart 3: 2020 Income in Some Tenth District States Exceeded Hypothetical, Non-pandemic Baseline

Notes: The non-pandemic baseline is a hypothetical scenario that holds pre-pandemic wages and employment constant throughout the year. Employment-related income—including the sum of wages and unemployment insurance benefits throughout the year—is then compared with this hypothetical scenario.

Sources: BLS, Nolo Legal Encyclopedia, and author’s calculations.

The chart shows that income from wages and unemployment benefits in 2020 resulted in incomes greater than what might have been expected in Nebraska, Kansas, and Missouri. These states have lower wages in general and experienced a higher concentration of pandemic-related job losses in lower-paying industries. Accordingly, weekly unemployment benefits including federal enhancements replaced a larger share of wages than in other states in the region.

In contrast, higher-wage states and those with more job losses in higher-wage industries, such as mining, had total incomes slightly below the non-pandemic baseline. In Wyoming, nearly 40 percent of job losses in 2020 were in the mining sector, which had the highest average weekly wage of all industries in the state. Accordingly, total income in Wyoming in 2020 was almost 2 percent lower than would be expected without the pandemic. Although job losses in the mining sector constituted a smaller share of total job losses in Oklahoma, New Mexico, and Colorado, they were still the primary driver behind the decline in income (relative to the non-pandemic baseline) in those states.

Through the first half of 2021, economic conditions in the Tenth District continued to improve. The passage of the Coronavirus Response and Relief Supplemental Appropriations (CRRSA) Act at the end of December 2020 reinstituted federal enhancements to unemployment insurance at $300 per week. As vaccinations increased and the virus abated, job gains began to pick up speed. The policy support early in 2021 was thus similar to that of 2020:Q3. Alongside an improving labor market, income from wages and unemployment benefits likely returned to pre-pandemic levels.

Federal enhancements to unemployment insurance supported incomes during the pandemic, even resulting in surplus income in some areas. The economic disruptions of the pandemic would have been much more severe without these programs. Going forward, however, unemployment insurance is likely to play a more limited role in supporting incomes. Some states, including Missouri, Nebraska, Oklahoma, and Wyoming, stopped participating in the federal programs supplementing state unemployment insurance programs. Federal enhancements are scheduled to end for the remaining states no later than September 6. As the labor market improves, continued job gains and wage pressures resulting from labor shortages will likely become more important to support income than federal enhancements.

Endnotes

-

1

I use average weekly wage and employment data for two-digit North American Industry Classification System (NAICS) industries in each county from the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ Quarterly Census of Employment and Wages (QCEW). For each job lost, I calculate the value of lost wages using the average weekly wage from 2020:Q1 from the appropriate county-industry pair.

-

2

Total income in 2020 was also strongly supported by direct payments to households enacted through the CARES Act. These direct payments are not included in the measure of income used in this study. To calculate total income, I first calculate job losses in each county and each major industry relative to the first quarter. I then use the average weekly wage in each county-industry pair in the first quarter to compute total average weekly wages for remaining jobs in each county-industry pair and sum them to the state level. By statute, each state has a different formula for determining unemployment benefits; I apply these 50 different calculations to the county-industry pairs where jobs were lost and sum to the state level to arrive at total weekly unemployment benefits in a given state.

John McCoy is an assistant economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City or the Federal Reserve System.