As the COVID-19 pandemic hit U.S. shores, a deep and broad downturn gripped the economies of both the United States and the Tenth Federal Reserve District, which includes Colorado, Kansas, western Missouri, Nebraska, northern New Mexico, Oklahoma, and Wyoming._ Numerous stay-at-home orders were put in place across the country to slow the disease’s spread. In addition, mandatory social distancing restrictions led many businesses to close, shut down certain operations, or reduce on-site staffing levels.

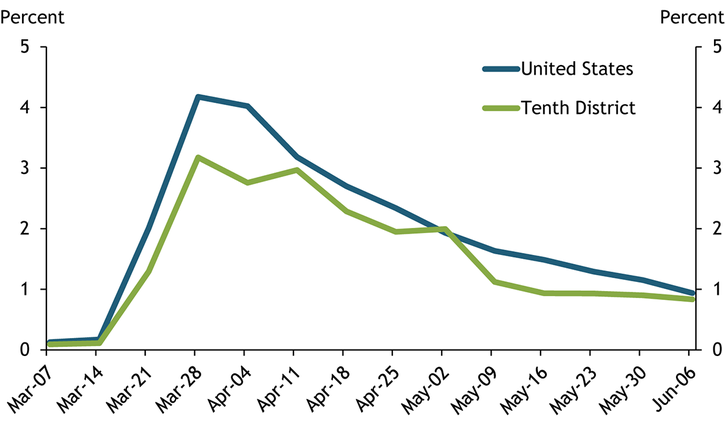

As businesses closed and consumers stayed home, job losses mounted. Within just a couple of weeks, initial claims for unemployment insurance skyrocketed from historically low levels to historically high levels. Chart 1 shows the weekly number of initial claims for unemployment insurance as a share of the February 2020 labor force. In the last week of March, 3.2 percent of the Tenth District labor force and 4.2 percent of the U.S. labor force filed for unemployment benefits. New claims have declined since these peak levels but remain elevated, suggesting the pace of job losses is slowing. In total, more than 21 percent of the Tenth District labor force have filed for unemployment benefits since mid-March—an unprecedented level in recent history._

Chart 1: Weekly Initial Claims for Unemployment Insurance as a Share of the Labor Force

Note: Weekly initial claims for unemployment insurance are divided by the labor force in February 2020.

Sources: Department of Labor and Bureau of Labor Statistics (Haver Analytics).

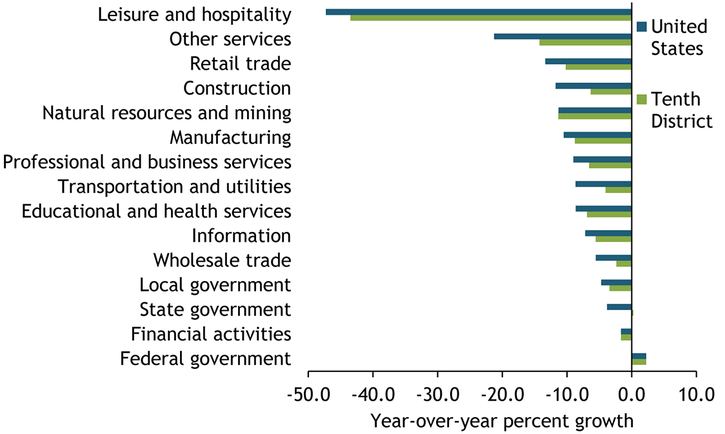

Employment has declined in almost every industry since the shutdowns started, but job losses have been slightly less severe in the Tenth District thus far. Chart 2 shows the percent change in employment by industry in April 2020 compared with April 2019 for both the United States (blue bars) and Tenth District (green bars). The leisure and hospitality sector—which includes hotels, restaurants, and recreational and arts establishments—has been the hardest hit, with employment down 43.5 percent in the Tenth District and 47.2 percent in the nation. The other services sector, which includes salons, repair shops, and retail establishments, also experienced dramatic job losses, though declines were smaller in the Tenth District than in the United States. Job losses in the construction sector have also been smaller in the Tenth District, likely due to differences in local business restrictions. In most parts of the Tenth District, the construction industry was deemed an essential business and operations were allowed to continue, albeit with social distancing measures in place. Although total job losses across industries have been drastic, about 80 percent of workers in both the Tenth District and the United States expect their job separations to be temporary._

Chart 2: U.S. and Tenth District Employment by Industry, April 2020 versus April 2019

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics (Haver Analytics).

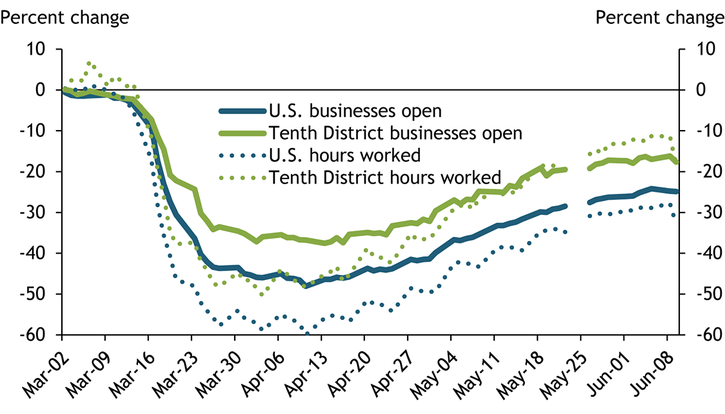

Business activity has also fallen substantially as measured by real-time indicators, though the Tenth District again appears to have fared slightly better than the nation as a whole. Chart 3 uses information from Homebase, a small-business payroll processing company, to show how the number of consumer-oriented businesses open and employee hours worked have changed since January. The number of businesses open in both the United States and the Tenth District started to fall by mid-March and had declined steeply by mid-April. However, the decline was much larger in the nation (48 percent) than the Tenth District (37 percent). Similarly, by mid-April, the number of hours worked had declined by more nationwide (60 percent) than in the Tenth District (50 percent). As of early June, the number of U.S. businesses open and hours worked had recovered slightly, but remained 20 to 25 percent below pre-COVID levels.

Chart 3: Change in Business Activity Relative to Base Period (January 4–31)

Notes: Data primarily consist of restaurant, food and beverage, retail, and services establishments and are largely individual-owned or operator-managed. An artificial break in the series was created for Memorial Day, May 25, as many businesses were closed for the holiday.

Source: Homebase (Haver Analytics).

Unsurprisingly, business revenue fell alongside the measures shown in Chart 3. However, as businesses reopen, revenue has started to climb as well. Information from Opportunity Insights Economic Tracker shows that relative to January levels, small business revenue was down close to 18 percent as of early June, but up from a low of −41 percent at the end of March. Across Tenth District states, the decline in small business revenue as of early June ranged from 18 percent (New Mexico) to an actual increase of 4 percent (Wyoming). The smaller contraction in early June indicates that conditions are improving, though the timing of a full recovery and the outlook for small businesses remains uncertain.

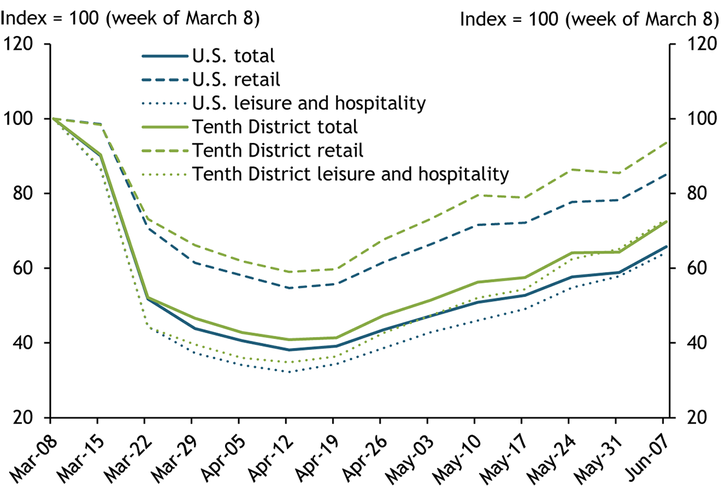

Foot traffic to businesses fell at a similar pace in both the Tenth District and the nation as a whole during the initial stage of the pandemic. However, foot traffic has picked up slightly faster in the Tenth District, where stay-at-home orders were lifted earlier than in other parts of the United States. Chart 4 displays the indexed level of foot traffic of individuals to U.S. and Tenth District businesses, with a reading of 100 indicating that the level of foot traffic in a given week was unchanged from March 8._ In addition to foot traffic to all businesses (solid lines), Chart 4 highlights foot traffic to retail establishments (dashed lines) and leisure and hospitality establishments (dotted lines), as they more closely track consumer spending. Total foot traffic in both the United States and Tenth District bottomed out during the week of April 12 with a reading near 40, indicating a 60 percent decline in foot traffic relative to early March. The decline was steeper for leisure and hospitality establishments (around 65 percent) than for retail establishments (about 55 percent), likely reflecting that a greater share of retail establishments, such as grocery and big-box stores, was deemed essential and therefore more likely to be open for business. Traffic began to improve by late April in the Tenth District, but as of early June remained approximately 27 percent below levels in the first week in March (−7 percent retail, −27 percent leisure and hospitality). The pace of improvement was a bit slower for the nation as a whole, with traffic still 34 percent below early March levels (−15 percent retail, −36 percent leisure and hospitality).

Chart 4: Change in Weekly Foot Traffic to Business Establishments

Note: Trips are indexed to the number of trips for the week of March 8.

Source: Safegraph.

Consumer spending has also shown signs of improvement recently. According to the Opportunity Insights Economic Tracker, U.S. consumer spending was down 13 percent as of early June relative to January levels, but up from −33 percent at the end of March. In the Tenth District, declines in consumer spending in early June relative to January have ranged from 17 percent (New Mexico) to 2 percent (Oklahoma). A recovery in consumer spending will be important for the overall economic recovery: personal consumption represents approximately 70 percent of total U.S. gross domestic product.

The COVID-19 pandemic and the associated efforts to contain it have led to a decline in economic activity unprecedented in both severity and speed. Recent data suggest the decline has bottomed out. Businesses have started to reopen and traffic to businesses has improved, especially in the Tenth District. However, the economy remains dramatically weaker than it was before the pandemic, and it is unclear when activity will recover to pre-pandemic levels.

Endnotes

-

1

Throughout this article, Tenth District data aggregate state-level data for these seven states.

-

2

Data for initial claims for unemployment insurance do not include claims filed by self-employed and contract workers for Pandemic Unemployment Assistance as part of the CARES Act. Across Tenth District states, total claims for unemployment insurance equaled 14.3 percent of the labor force in Colorado, 21.2 percent in Kansas, 24.2 percent in Missouri, 15.9 percent in Nebraska, 17.3 percent in New Mexico, 33.4 percent in Oklahoma, and 17.1 percent in Wyoming. At the national level, total claims for unemployment insurance totaled 26.9 percent of the labor force.

-

3

Authors’ calculations based on data from the Consumer Population Survey.

-

4

Foot traffic data are from Safegraph, which uses anonymized cell phone information that records the location of people as they leave their homes to visit establishments each day. We aggregate this information using “version 2” of the data to weekly counts and index each week to the baseline week of March 8.

Jason P. Brown is a research and policy officer at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City. Alison Felix is a senior policy advisor at the bank. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City or the Federal Reserve System.