Firms in Nebraska may view the development and availability of artificial intelligence (AI) products as an opportunity to address challenges in finding labor, managing the cost of labor, or both. While AI adoption remains limited, questions have arisen about its economic impact. Some investigative work has explored the level of exposure of existing workers to AI. However, in parts of the country like Nebraska where finding labor has been a challenge, businesses may perceive AI adoption as a potential opportunity.

Section 1. Persistent Labor Shortages and Rising Labor Costs May Lead to AI Adoption at Nebraska Firms

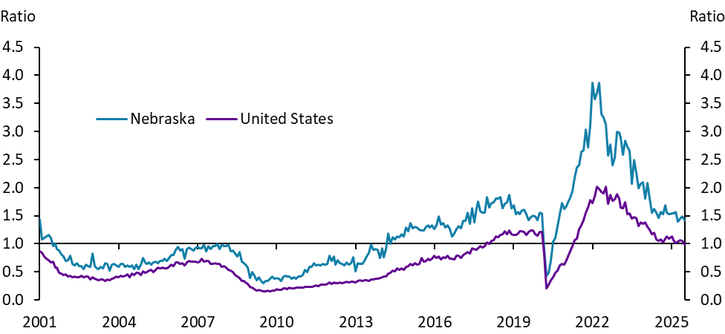

Many Nebraska firms have struggled to find talent over the past decade. Since mid-2014, and other than briefly during the early pandemic, job openings have outnumbered unemployed workers in the state (Chart 1). As of 2025, more than 1.5 jobs remained open per one unemployed person. Since data on job openings were first released in 2001, there have been more openings than available workers 46% of the time in Nebraska compared with just 25% of the time nationwide.

Chart 1. Job Openings to Unemployed Ratio

Sources: BLS (JOLTS), BLS (LAUS), Haver Analytics.

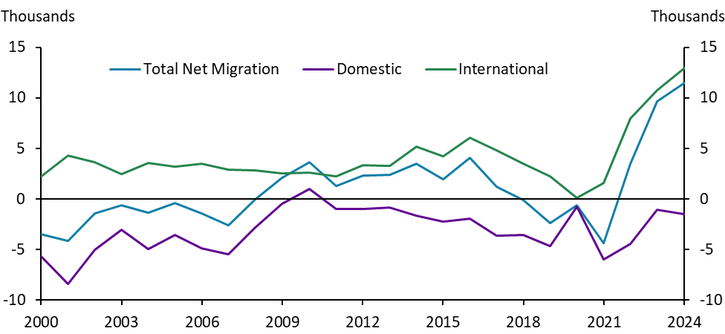

Over the past 25 years, Nebraska's population growth has been limited by residents moving to other states, reducing the available workforce. Although net population has increased in Nebraska, most of the growth has come from immigration (Chart 2). As previous work has shown (Nebraska Economist 2023), many current residents leaving for other states have been working-age adults, and many with college degrees.

Chart 2. Nebraska Migration

Sources: Census Bureau, Haver Analytics.

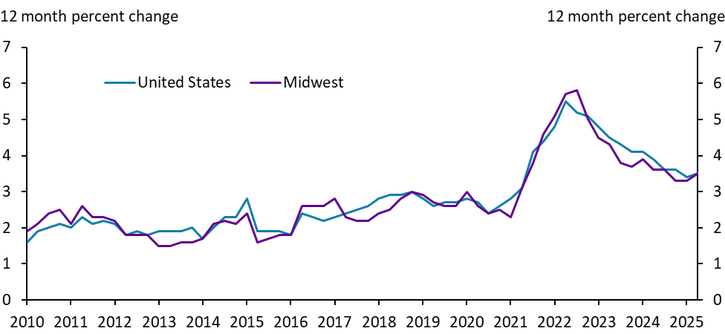

In addition to labor scarcity, employment costs have increased. In both the United States and Midwest region, total employment costs—wages, salaries, and benefits—rose by about 3.5 percent in the first half of 2025 (Chart 3). Although these costs have moderated since 2022 when inflation was particularly high, payroll expenses have continued to grow faster than the years prior to the pandemic.

Chart 3. Total Employment Cost Index

Sources: BLS (ECI), Haver Analytics

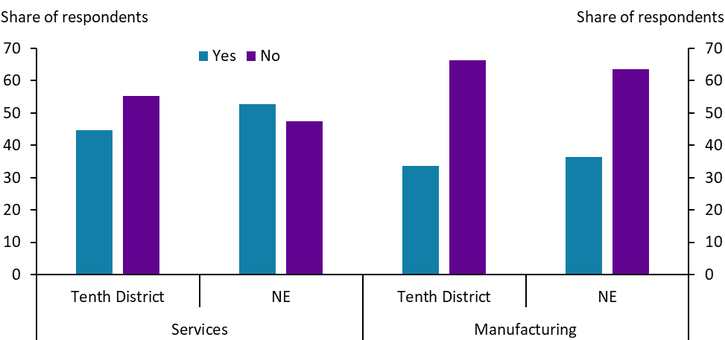

Artificial intelligence has affected most Nebraska services firms, perhaps partially in response to labor scarcity or rising costs. Surveys from the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City found that 52% of service-providing firms and 36% of manufacturing firms in Nebraska were impacted by AI developments — rates that were higher than the broader region (Chart 4). Regionally, among firms reporting AI effects on business plans, 44% expanded AI use this year, 33% began using AI this year, and 21% plan future adoption. Understanding which jobs have tasks suitable for AI and their prevalence in Nebraska will be key to explaining variation in regional adoption.

Chart 4. Have Developments in AI Affected Your Company’s Business Plans?

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City

Section 2. Certain Occupations More Likely to Be Affected by Artificial Intelligence

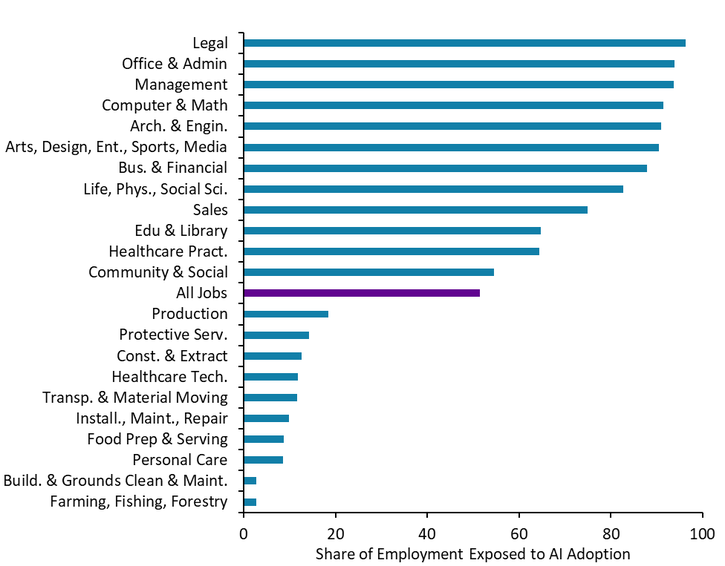

Office-based occupations may be most likely to be affected by the emergence of AI tools. About half of the current workforce has been in an occupation where at least 50% of tasks were exposed to AI in recent years (Chart 5). However, employment in AI-exposed jobs has varied widely across job families. More than 90% of employment in six job families – such as legal professions, management professions, or computer and math professions – was exposed to AI. Consequently, firms that struggled with labor shortages in these job families may have turned more readily to AI tools.

Chart 5. Share of U.S. Employment by AI Exposure, 2022-24 Average

Note: This chart uses artificial intelligence exposure scores as described by Eloundou and co-authors. Specifically, this chart uses the most expansive definition of exposure (“E2” exposure in the paper), including tasks both directly exposed to artificial intelligence and tasks that could be indirectly exposed to artificial intelligence through the development of software using artificial intelligence tools. A task is considered exposed to artificial intelligence if the time needed to complete the task could be halved by the use of an AI tool. A job is considered exposed to occupations if at least 50% of the tasks needed to perform the job are exposed to AI.

Sources: BLS (OEWS), Eloundou et al (2024), author’s calculations..

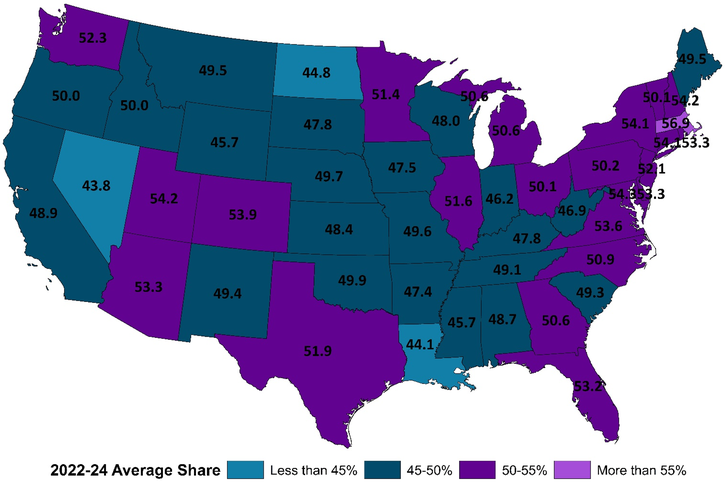

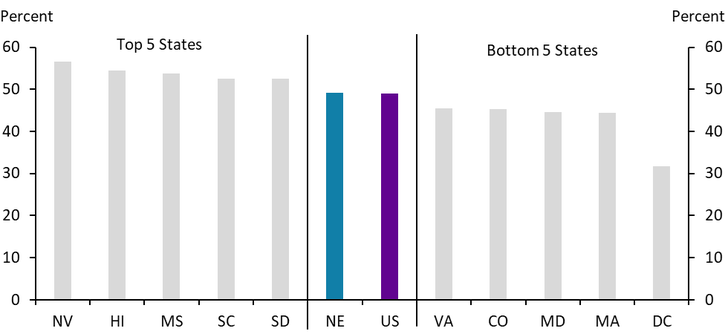

As in the nation, a significant number of jobs in Nebraska may be affected by AI, but a slightly smaller share than other states. Between 2022 and 2024, about 50% of employment in Nebraska was exposed to AI (Map 1). The statewide exposure in Nebraska was only slightly higher than the least exposed state (Nevada) where a higher share of employment is found in occupations typically associated with the leisure and hospitality industry. Conversely, statewide exposure to AI in Nebraska has been only slightly lower than the most exposed state (Massachusetts). Other than the most and least exposed states, exposure to AI has been fairly similar across states.

Map 1. Employment in jobs with at least 50% of tasks exposed to artificial intelligence

Sources: BLS (OEWS), Eloundou et al (2024), author’s calculations.

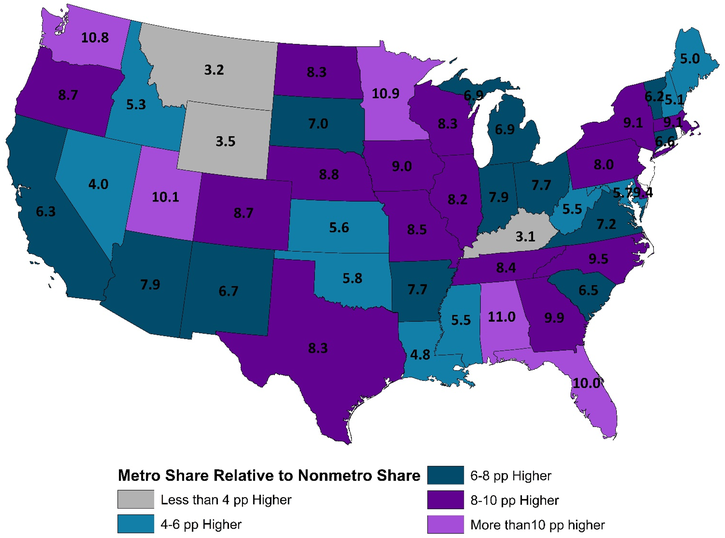

Within states, however, occupations more exposed to AI have been located in metropolitan areas. In Nebraska, the share of employment in jobs exposed to AI was nearly 9 percentage points higher in metro areas relative to nonmetro areas (Map 2). This gap ranked among the largest across states and exceeded the 8-percentage point gap for the nation. Firms in Nebraska's metro areas—Omaha, Lincoln, and Grand Island—may be better positioned to adopt AI tools to address labor scarcity or cost challenges, given the workers they have tended to employ.

Map 2. Employment in AI Exposed Jobs, 2022-24 Average

Sources: BLS (OEWS), Eloundou et al (2024), author’s calculations.

Section 3. Could High Turnover or High-Cost Jobs Spur AI Adoption?

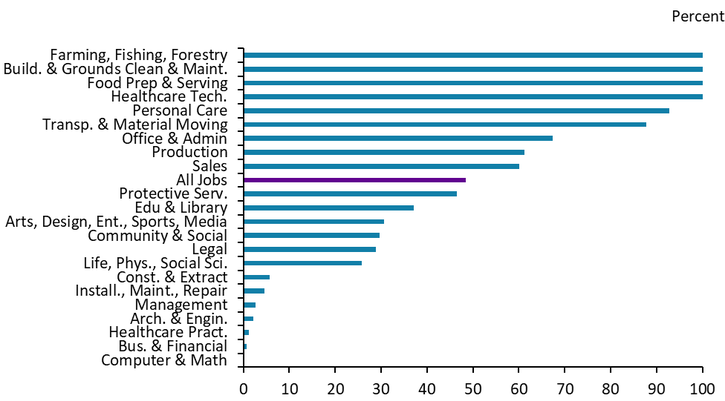

Occupations prone to relatively high turnover could be more affected by the availability of AI tools. Nationwide across all job families, about half of employment was in a high turnover occupation between 2022 and 2024. In some job families – such as farming or food preparation and serving – nearly all of 2022-24 employment was in a high turnover occupation (Chart 6). Firms with many high turnover employees may face dual constraints: labor scarcity might make these positions harder to fill, while higher non-wage costs could arise from increased training needs. Consequently, firms highly exposed to turnover might more readily adopt AI tools to address these challenges.

Chart 6. Share of Occupational Employment in High Turnover Jobs, 2022-24 Average

Note: High turnover are occupations with projected separations rate of at least 10% over the next decade. The BLS defines separations as “the projected number of workers permanently leaving an occupation.”

Sources: BLS (Employment Projections), author’s calculations.

With some small differences, the share of employment in higher turnover occupations has been similar across states. For both the U.S. and Nebraska, slightly less than 50% of employment was in a high turnover occupation between 2022 and 2024 (Chart 7). Employers might deploy AI tools to address labor scarcity or cost concerns in positions that experience high turnover if most tasks performed by those roles can be performed by AI.

Chart 7. Share of State Employment in Higher Turnover Occupations, 2022-24 Average

Sources: BLS (Employment Projections), author’s calculations.

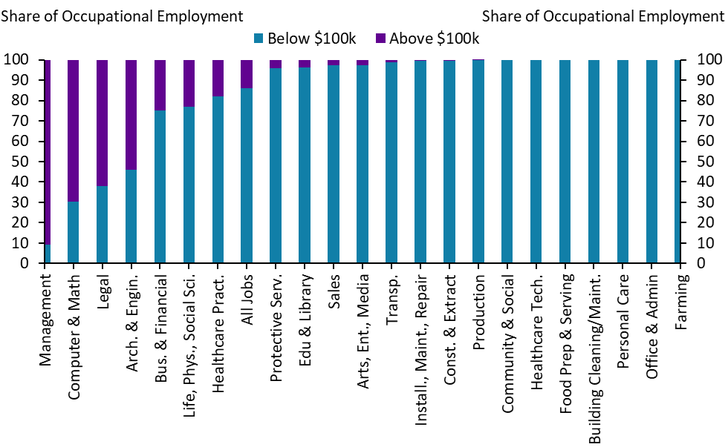

In addition to higher costs that might arise from training high turnover positions, firms might also adopt AI to address rising labor costs in traditionally high-salary positions. Across the U.S., a vast majority of employment in most job families earned less than $100,000 per year between 2022 and 2024. Only in four job families did a majority of workers earn more than $100,000 per year (Chart 8). However, high salaries were common among managers (90 percent), computer and mathematics professionals (70 percent), and legal professionals (65 percent).

Chart 8. Share of Employment by Annual Salary, 2022-24 Avg.

Sources: BLS (OEWS), author’s calculations.

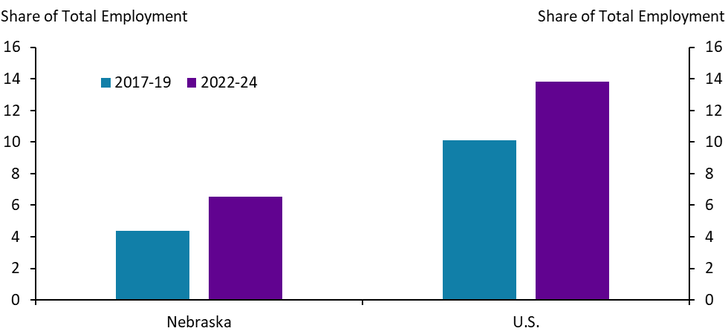

High-salary occupations represented a smaller share of Nebraska's workforce compared to the national average. Between 2022 and 2024, after accounting for inflation and regional cost-of-living differences, the proportion of high-salary employment increased from pre-pandemic levels in both Nebraska and the U.S. (Chart 9). Though the share of high-salary employment has grown, Nebraska employers adopting AI to address higher labor costs might achieve fewer savings than firms elsewhere in the country.

Chart 9. Share of Employment in High Salary Occupations

Note: average salary is adjusted for inflation using headline PCE inflation (BEA) and for regional differences in cost of living using regional price parities (BEA).

Sources: BLS (OEWS), BEA, author’s calculations.

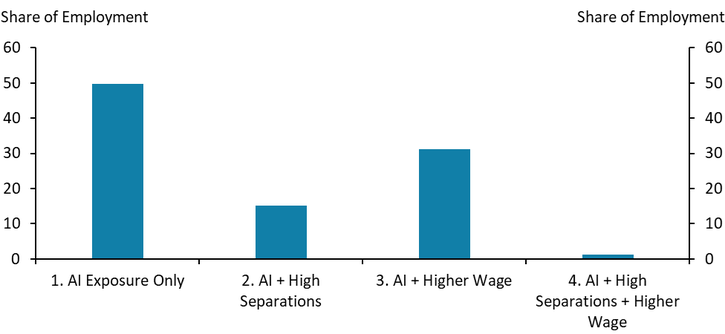

In Nebraska, the disruption to employment from AI adoption could vary depending on implementation strategy. If employers widely adopt artificial intelligence tools regardless of occupational turnover or labor costs, nearly half of jobs in Nebraska could face disruption (Chart 10, Bar 1). If firms prioritize AI adoption in high-turnover occupations (Bar 2), about 15% of employment might be affected. Focusing AI adoption on high-salary occupations (Bar 3) could disrupt nearly 30% of Nebraska jobs. However, firms attempting to address both labor scarcity and cost issues simultaneously through the adoption of AI might only affect 2% of current employment.

Chart 10. Nebraska Employment in Jobs by AI Exposure, Separations Rate, and Salary, 2022-24 Average

Sources: BLS (OEWS), BLS (Employment Projections), BEA, Eloundou et al (2024), author’s calculations.

The adoption of artificial intelligence remains in early stages, requiring further study to understand its impact on national and regional economies. While firms' motivations for deploying AI tools need additional research, addressing labor scarcity and costs could serve as primary drivers. Given Nebraska's current job composition, AI could potentially augment or replace a substantial amount of work across the state. However, persistent labor shortages suggest near-term AI adoption might help firms fill chronically vacant positions rather than significantly disrupt current levels of employment.

Reference

Eloundou, T., Manning, S., Mishkin, P. and Rock, D. (2024). “GPTs are GPTs: Labor market impact potential of LLMs”. Science, 384(6702), pp.1306–1308. doi:External Linkhttps://doi.org/10.1126/science.adj0998.

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City or the Federal Reserve System.