Labor scarcity has been an increasingly important issue in Nebraska for several years, but particularly in the wake of the pandemic. Across the nation, reports of worker shortages have been unprecedented in terms of both geographic scope and duration. The imbalance between strong demand for labor and a constrained labor supply has been more pronounced in Nebraska than many other states. Despite the significant need for workers in the state, however, Nebraska’s labor force has not expanded as quickly as what might be needed to resolve the shortages.

Strong Demand for Labor in Nebraska

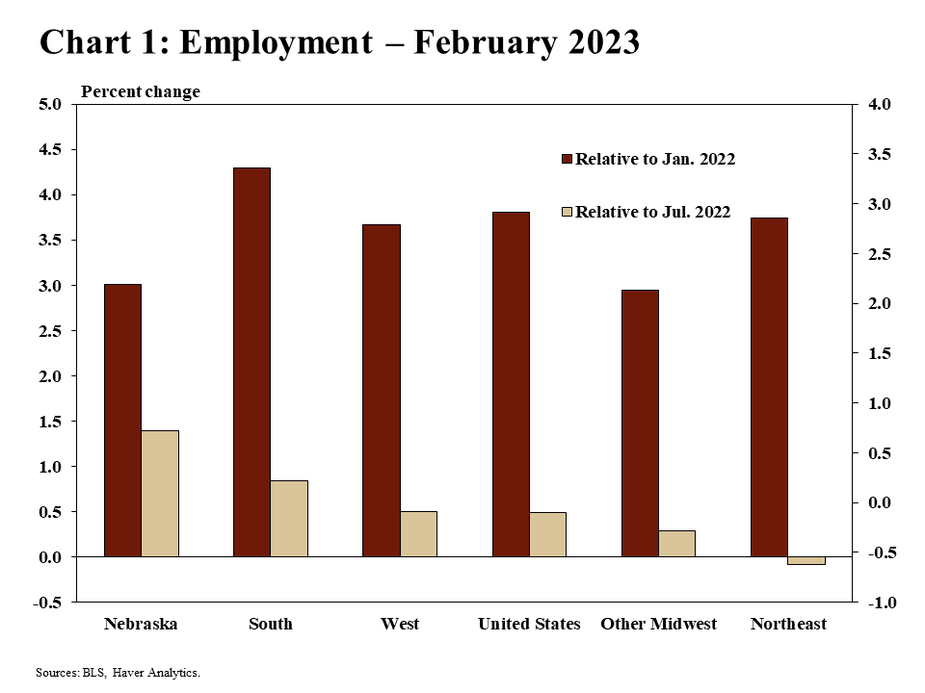

Employers in Nebraska added jobs at a robust pace in 2022 and early 2023. Like other areas of the country, the number of jobs in Nebraska exceeded the previous year by more than 2 percent in January (Chart 1). However, employment in Nebraska grew more steadily throughout the year than other areas of the country. In the second half of 2022 and early 2023, job growth in Nebraska was higher than other regions of the country, including the rest of the Midwest, at 1.4%.

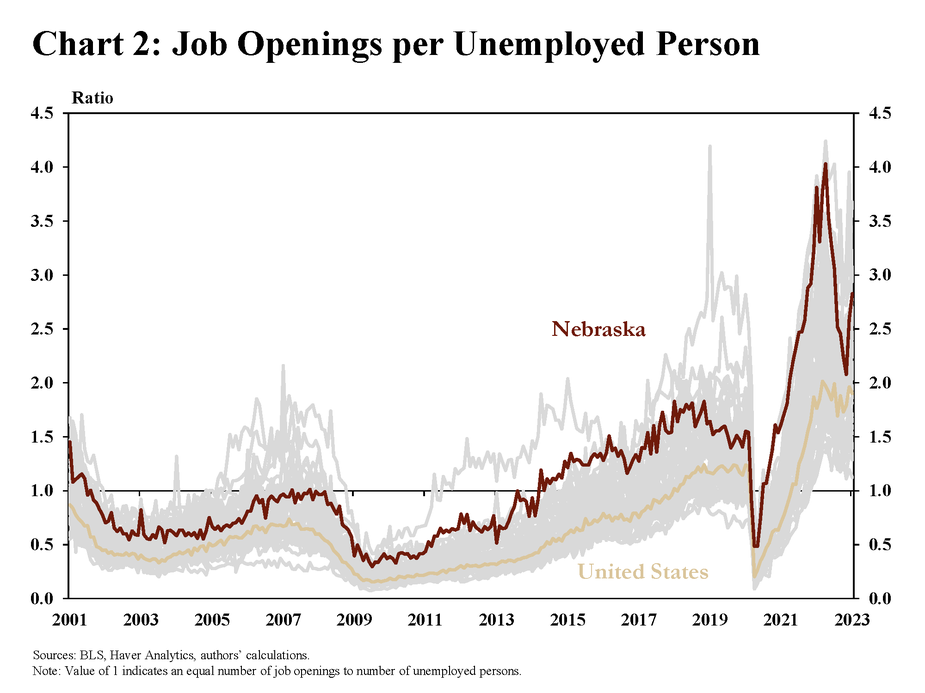

Despite robust job growth, employers have sought to hire even more workers. The number of job openings in Nebraska, relative to the number of unemployed people has remained historically high. In January there were 2.8 job openings per unemployed person in the state (Chart 2). Though this ratio was less than the all-time high of more than 4 job openings per unemployed person during the summer of 2022, the ratio has been substantially higher than pre-pandemic levels. Beyond Nebraska, there have been more open jobs than unemployed people in all states since early 2021.

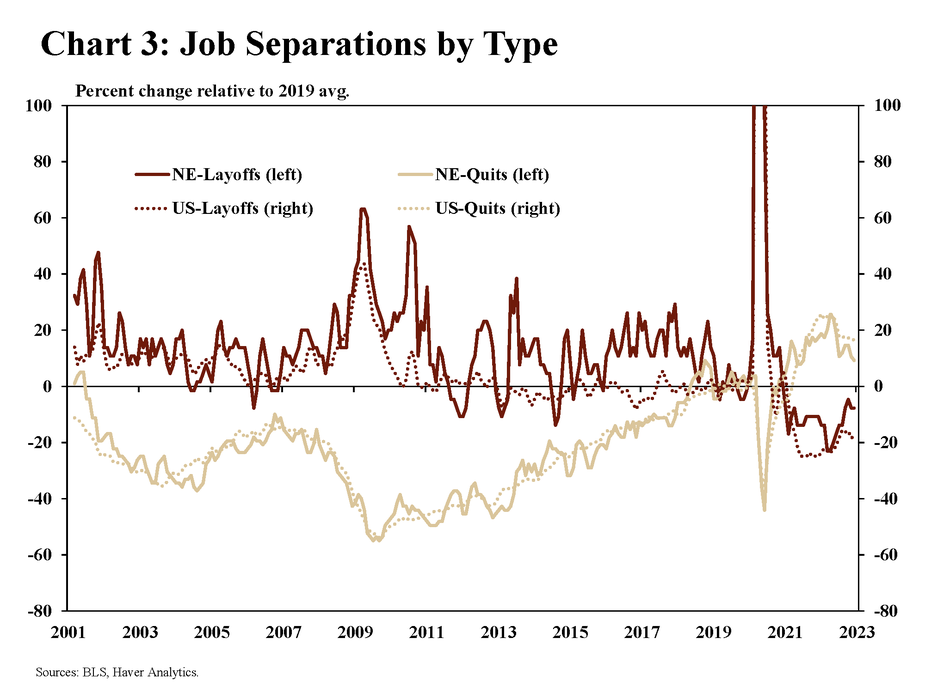

With the number of job openings elevated, job seekers have more frequently pursued new employment opportunities. The number of individuals voluntarily leaving jobs has remained elevated, even relative to a historically tight pre-pandemic labor market (Chart 3). The number of quits peaked during the summer of 2022 and remained close to this level through the end of the year. Alongside more individuals voluntarily leaving jobs, employers have been reluctant to lay off employees. The number of layoffs has been less than 2019 for several years.

Limited Supply of Labor in Nebraska

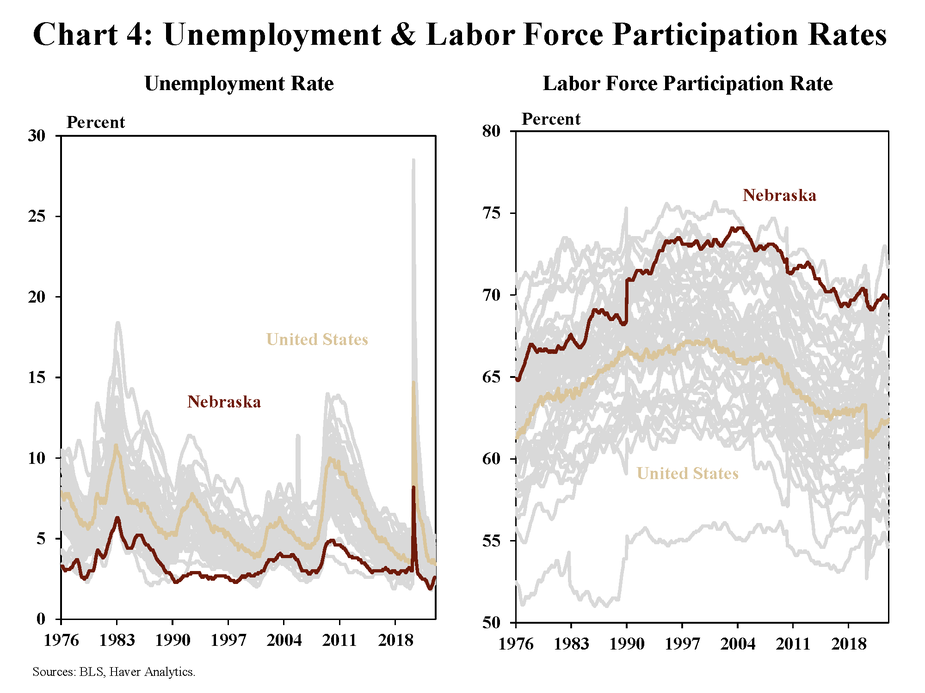

Labor availability has generally been more limited in Nebraska than other states over the past five decades. Since the mid-1970s, the unemployment rate in Nebraska has been one of the ten lowest among all states in almost every year (Chart 4). Furthermore, Nebraska had the lowest unemployment rate of all states in 23 of the 32 months between April 2020 and December 2022. Alongside persistently low unemployment, Nebraska’s labor force participation rate, the share of the state’s working-age population that is employed or looking for work, also regularly ranks among the highest across all states.

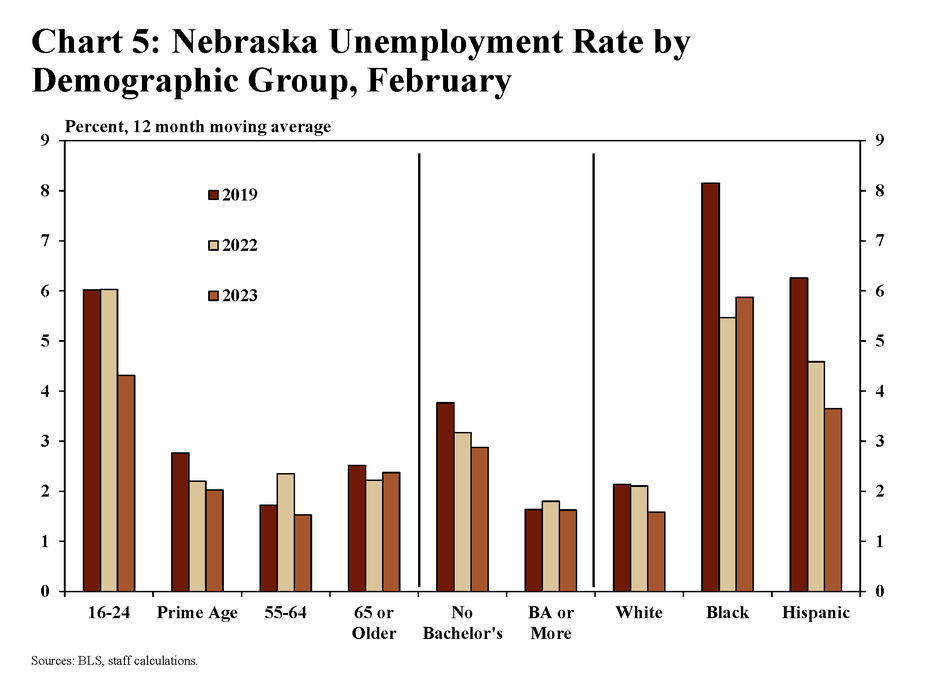

Moreover, unemployment rates across nearly all demographic groups declined by early 2023, generally below pre-pandemic levels. Improvements beyond 2019 levels by February 2023 have been particularly significant when considering the health of the pre-pandemic labor market. For example, unemployment among Black Nebraskans had fallen to a near historic low of 8.1% in February 2019 (Chart 5). By 2023, unemployment for Black Nebraskans had fallen by another 2.5 percentage points. While unemployment rates for other demographic groups have not fallen to the same extent, unemployment was at or near historic lows for all groups in February 2023.

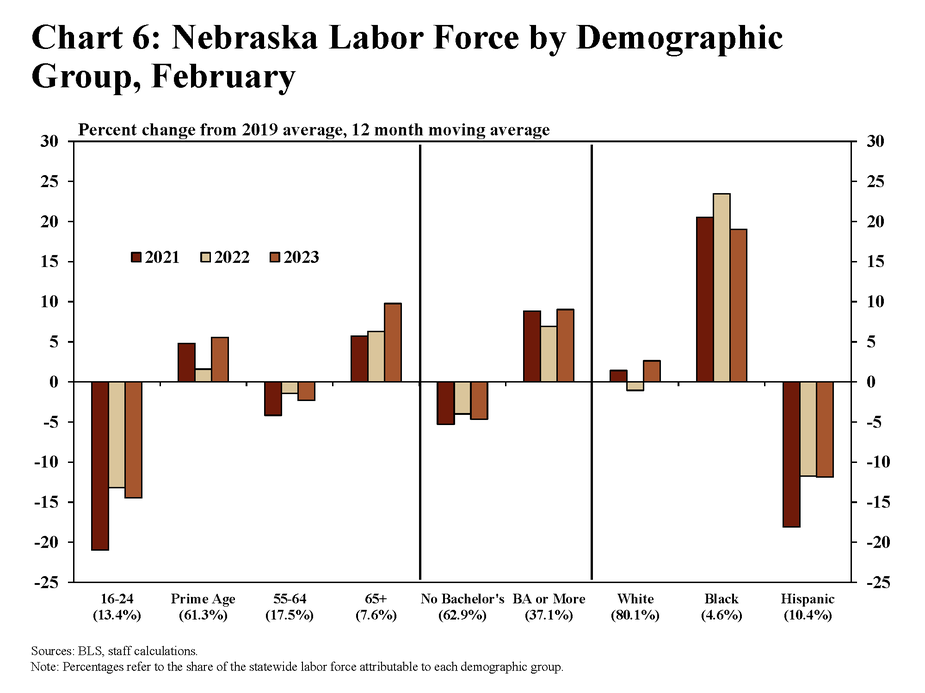

Although unemployment has declined across most demographic groups, the size of the labor force for some groups has not yet returned to pre-pandemic levels. Most notably, the Hispanic labor force in Nebraska was still about 12 percent less than in 2019 as of February 2023 (Chart 6). In addition, the number of individuals in the labor force between the ages of 16 and 24, and those without a bachelor’s degree, also has not yet returned to pre-pandemic levels. The increase in the prime age labor force (those between ages 25 and 54) has been driven by additional individuals seeking work between ages 25 and 44. Early retirements have contributed to a smaller labor force for those between ages 45 and 64.

Prospects for Increasing Labor Supply

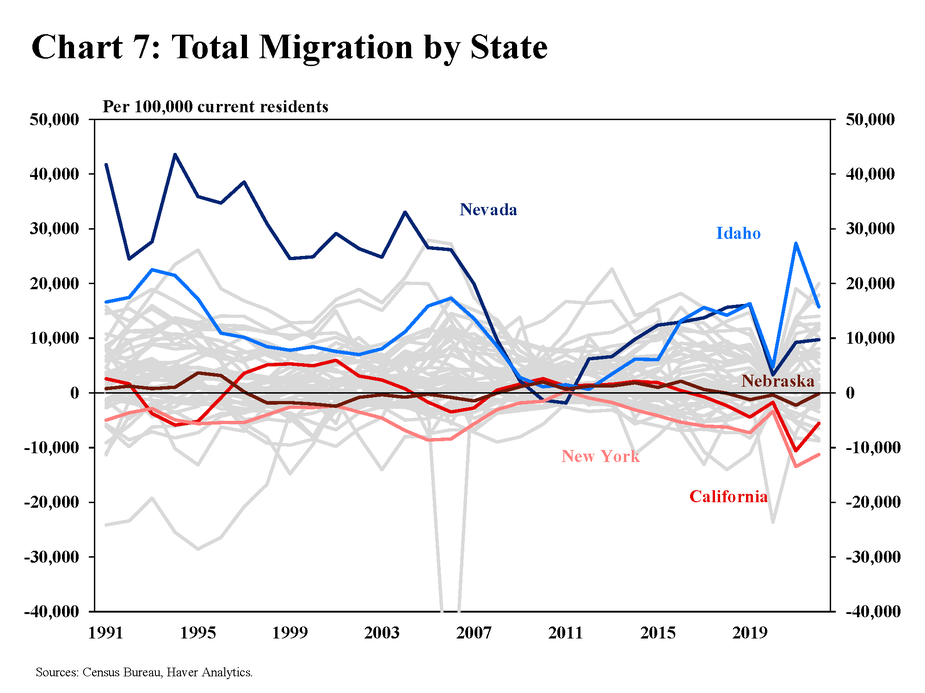

Attracting new people to the state may help strengthen the supply of labor but, historically, migration to Nebraska has been more limited than in other states. Since the early 1990s, migration to Nebraska (both domestic and international) has not exceeded 4,000 people per 100,000 existing residents. (Chart 7). Conversely, the state has also never lost more than 2,000 people to other locations. Other states, like Nevada and Idaho, have consistently added new residents through migration while states such as New York and California have attracted fewer people over the past decade.

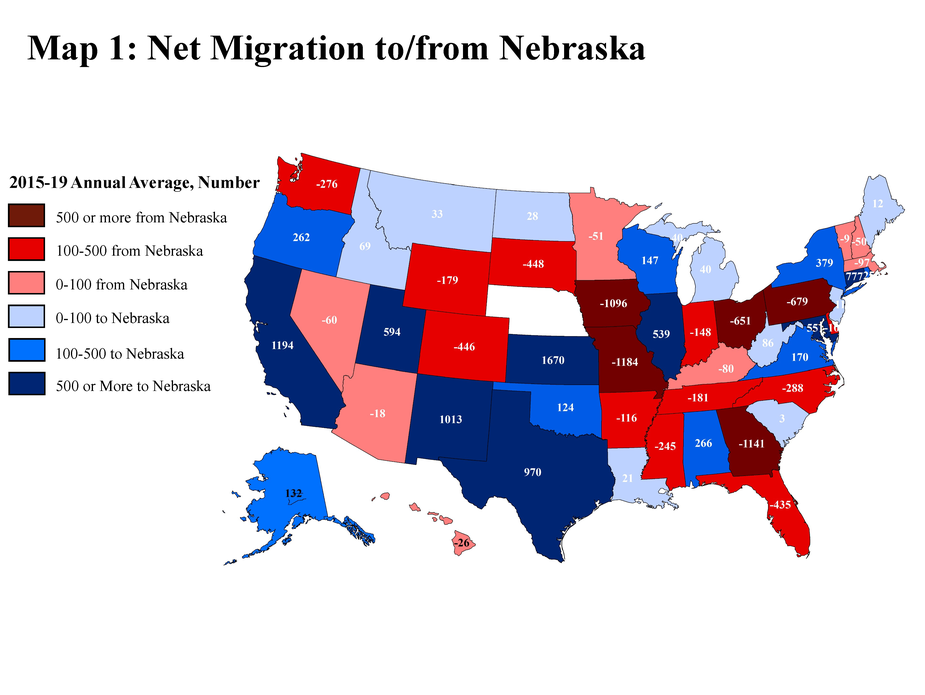

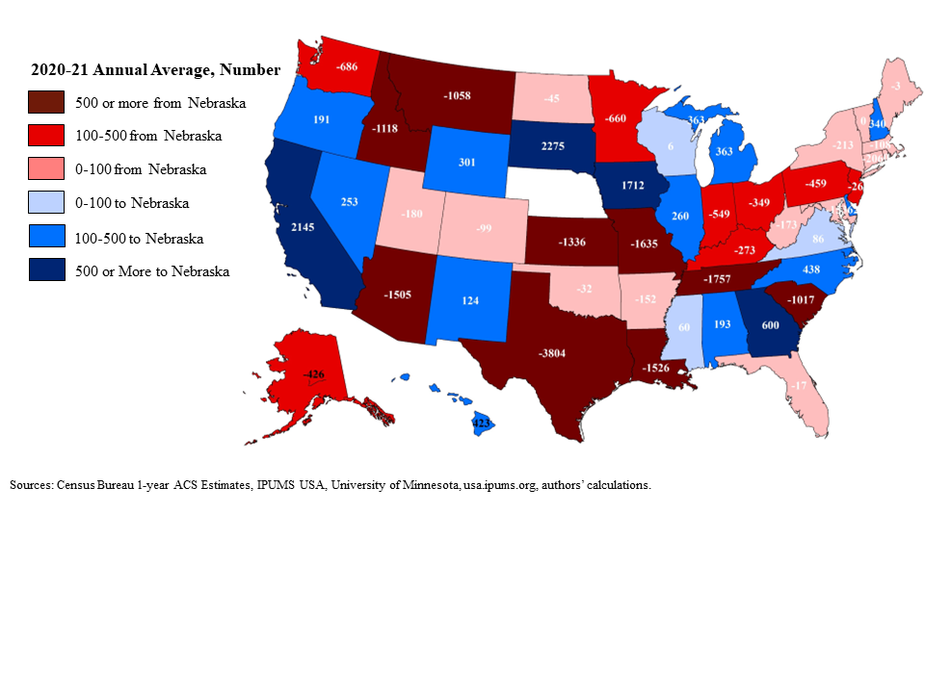

Historically, residents of Nebraska have left the state at a higher rate than those coming to the state from other parts of the country, and this trend was exacerbated by the pandemic. Prior to 2020, Nebraska had been losing residents to most neighboring states and other, more distant states with significant amenities or large population centers (Map 1). Beginning in 2020, the number of states to which Nebraska lost population increased. Only a handful of states – such as California, Oregon, Illinois, and Wisconsin – have been consistent sources of population gains for Nebraska.

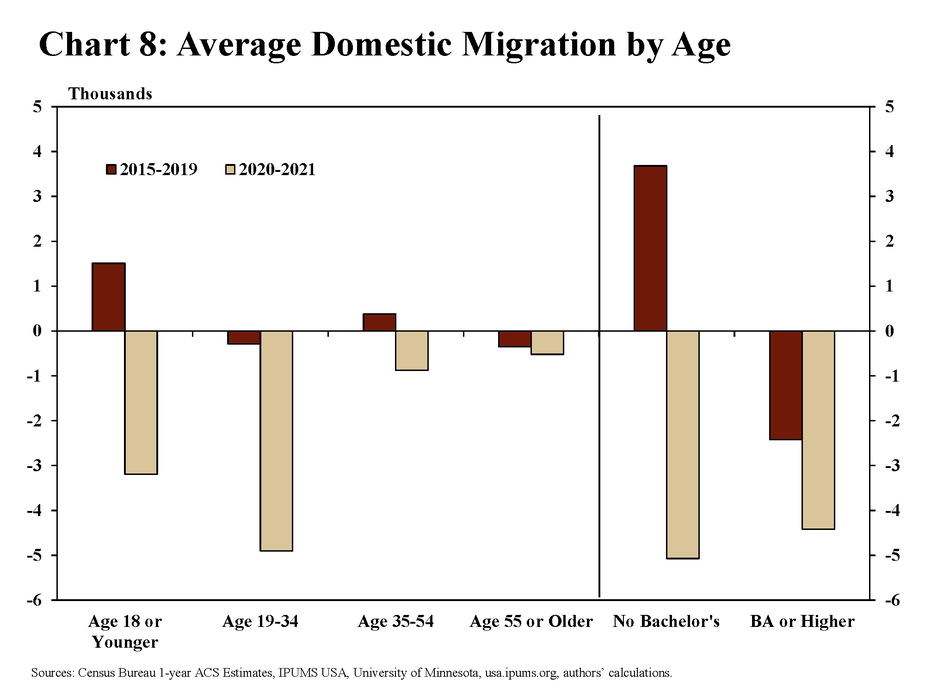

While the pandemic exacerbated migration from Nebraska to other states in general, the net loss of younger individuals, and those with higher levels of education has been a long-standing trend facing the state. Since 2015, individuals between the ages of 19 and 34 and those older than 55 have left the state at higher rates than other age groups (Chart 8). Similarly, an average of nearly 2,500 individuals with a college degree have been consistently leaving the state, on net, since 2015. The pandemic magnified these trends. The pandemic also reversed significant sources of in-migration among those younger than 19 and those between ages 35 and 54 likely encompassing families moving to the state and students enrolling in college.

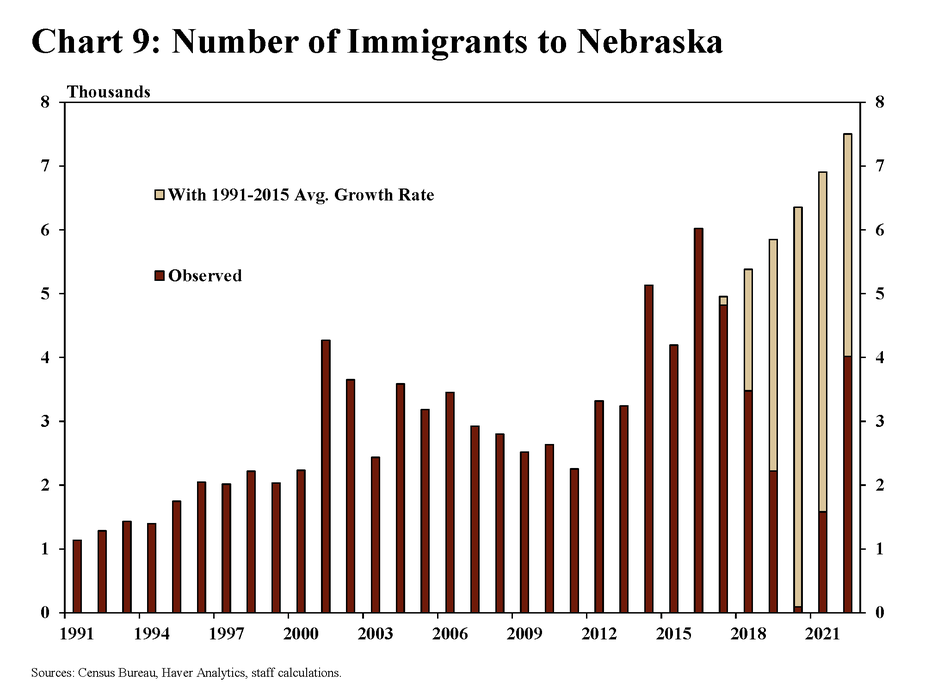

In recent years, reduced immigration has also contributed to slower labor force growth. Historically, immigration has been the largest component of migration to Nebraska. Between 1991 and 2015, immigration to the state increased by approximately 5 percent per year. Beginning in 2017, however, immigration to Nebraska, as well as the nation overall, began to fall steadily (Chart 9). Had Nebraska continued to add residents from abroad at the same rate prior to 2015, population in the state may have increased by an additional 19,000 individuals by 2022.

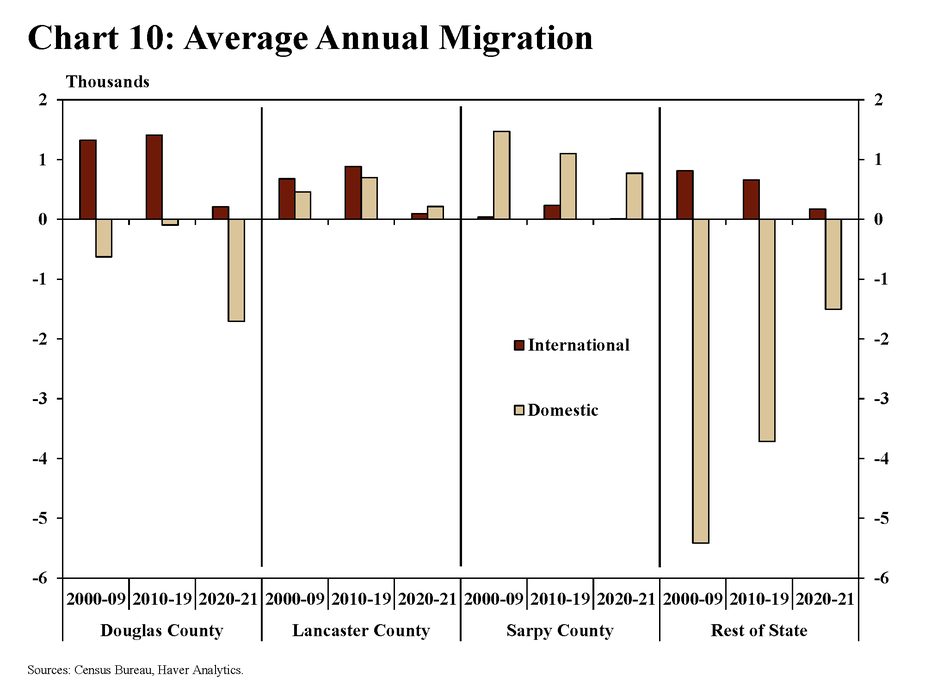

Though the state has faced long-standing trends of out-migration for decades, there are pockets within the state where migration trends have been more positive. Nebraska’s three largest counties have been areas where the number of people entering has been larger than the number that has left. Immigration has been a significant contributor to population growth in all areas of the state, boosting domestic in-migration or mitigating losses from out-migration (Chart 10). While domestic migration has contributed most significantly to population gains in Lancaster and Sarpy counties, immigration to Douglas County from other countries has been a primary factor driving population growth or mitigating population losses. Domestic out-migration has remained a significant headwind for rural parts of the state.

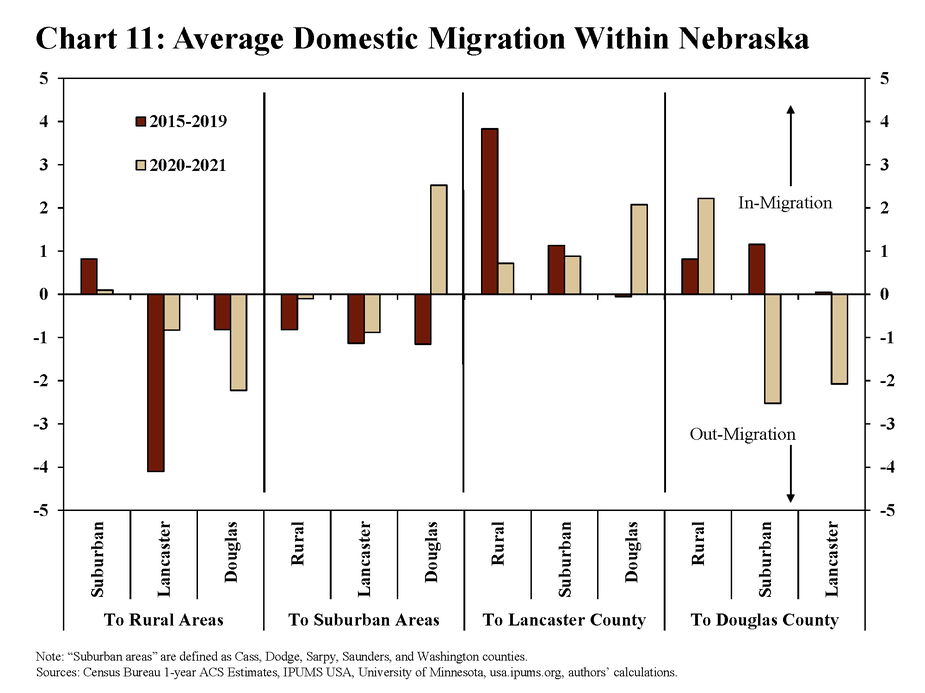

Though Douglas County has lost population to other areas of the United States, it had been a popular destination for migration within Nebraska until the onset of the pandemic. Beginning in 2020, migration to suburban and exurban locations near Omaha surged by nearly 2,500 people on average (Chart 11). Most individuals moving to suburban locations relocated from more densely populated areas, such as Douglas County. Lancaster County, on the other hand, was a consistently popular destination for Nebraskans, both before and during the pandemic. Residents in Nebraska’s most rural areas have tended to move to more populous counties, such as Douglas or Lancaster County, trends that continued in 2020 and 2021.

Nebraska’s economy has continued to expand even though demand for labor has far outpaced supply. However, labor constraints appear to be weighing on the growth prospects of many firms in the state. As the labor force for most demographic groups has largely recovered to – or exceeded – pre-pandemic levels, external sources of labor supply may be significant in addressing ongoing worker shortages. Increases in immigration could address some of these shortages, in addition to increasing population gains from other areas of the country. These strategies may be especially important for rural areas of the state, where populations declined at a more rapid pace through the pandemic.

Interested in digging deeper? Read "Workforce Imbalances Remain Important to U.S. Economic Outlook."