Job gains slowed this year across most sectors of the regional economy as labor markets continued cooling. In this edition of the Rocky Mountain Economist, we examine regional firms’ current employment outlook, compensation strategies, and recent staffing decisions as reported in the most recent External LinkKansas City Fed Manufacturing and Services Surveys. Businesses looking ahead to 2026 expect their employment levels to remain mostly unchanged on balance marking a downshift in the outlook for job gains compared with even a few months ago, when more firms expected to add staff throughout 2026. Survey data also indicate that regional wage gains are tied closely to changes in the price level or the cost of living and are no longer driven by competitive labor market conditions prevalent in recent years, when employers raised wages to attract new hires and retain certain skilled workers.

Stable Outlook for Job Gains on Balance

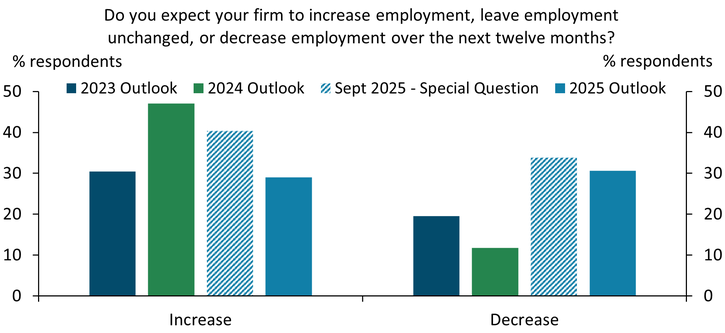

Employment expectations in the Rocky Mountain region changed considerably since last year. Regional employers signal a downshift in hiring expectations toward more stable employment levels throughout 2026, slowing from the hire-for-growth approach prevalent in previous years. Chart 1 shows that about 30 percent of businesses in November 2025 expect to increase their headcount over the next year (left-side blue bar), down from almost 50 percent at the end of 2024 (left-side green bar). This softer outlook for job gains became more prominent in recent months: In September 2025, 40 percent of firms anticipated increasing their workforce (patterned bar).

Chart 1: Employers in the Rocky Mountain region expect subdued hiring activity in 2026 on balance.

Notes: Data are from November 2023–25 Manufacturing and Services Surveys for Colorado, Wyoming, and New Mexico, asking about next year’s employment outlook. The special question during September 2025 specifically asked about the outlook for employment during 2026.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City.

As fewer firms report a favorable outlook for hiring over the coming year, more firms indicate that they expect their employment levels will decline in 2026 compared with their projections for 2025. The share of firms expecting lower employment levels over the coming year increased to 31 percent in November 2025, up from 12 percent in 2024 (right side of Chart 1, blue and green bars). Overall, reported outlooks for job gains are balanced between those planning to expand employment and reduce employment.

The drivers behind businesses’ hiring plans also shifted in the last year. At the end of 2024, many firms reported that they planned on hiring to alleviate strains on overworked staff or to add certain skills, especially in business and consumer service sectors. Hiring was just as likely to be motivated by the need to fill existing backlogs and orders for work as the need to meet expected growth in demand going into 2025. At the end of 2025, however, few firms indicate that they need to hire to alleviate constraints, and only those businesses that expect to see demand growth indicate that they plan to expand in 2026. Similarly, businesses are much more likely to cite waning demand as a headwind to hiring activity compared with last year, when the inability to find certain skills was the primary hiring constraint.

Wage Gain Drivers Have Shifted Toward Cost-of-Living Increases

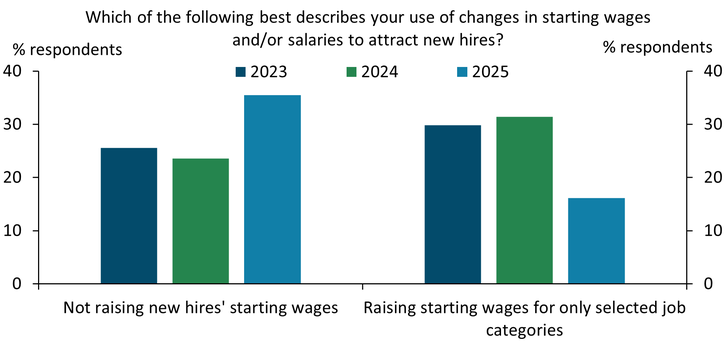

Over the past year, labor market conditions in the Rocky Mountain region continued to soften (Munoz Henao and Rodziewicz 2025). Going into 2026, businesses report they are less willing to raise wages for new and existing employees. Chart 2 shows that roughly one-third of firms anticipate holding wages for new hires stable in the coming year (left-side blue bar). Flat wage growth is a more common approach now compared with 2023 and 2024, when only a quarter of surveyed businesses were not raising wages for new hires (left-side dark blue and green bars, respectively).

Chart 2: More firms report that they are not raising wages for new workers, and fewer indicate that they are raising wages for select job categories.

Note: Data are from the November 2023–25 Manufacturing and Services Surveys for Colorado, Wyoming, and New Mexico.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City.

Businesses also indicate that they are less likely to raise wages for specific skills or job categories. Only 16 percent of firms reported that they are implementing wage increases for selected job categories, compared with nearly 30 percent in recent years (right side of Chart 2). This change in compensation strategy is consistent with businesses’ reports that they are less likely to seek new staff to meet specific needs or alleviate understaffing relative to their ongoing workload.

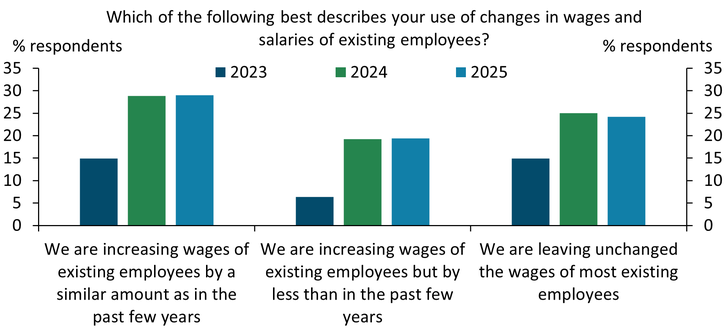

Throughout much of 2025, employment activity in the Rocky Mountain region and across the United States was characterized as a “low-hire, low-fire” labor market, with reduced labor turnover and limited hiring. In this environment, businesses are reportedly opting for more moderate wage increases in line with cost-of-living adjustments, rather than raising wages so they can retain workers amid competitive pressures. Chart 3 shows that roughly 29 percent of firms plan on keeping wage increases for current employees in line with recent years, whereas 19 percent anticipate raising wages more slowly and 24 percent anticipate keeping wages flat (blue bars). These reports are consistent with moderate wage growth compared with more elevated wage growth rates witnessed in 2023 (Greene and Rodziewicz 2024).

Chart 3: Shifts in compensation strategies suggest moderating wage growth for existing employees.

Note: Data are from the November 2023–25 Manufacturing and Services Surveys for Colorado, Wyoming, and New Mexico.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City.

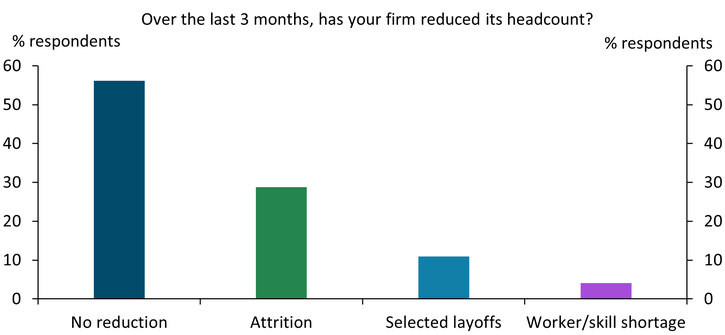

Most Firms Have Not Reduced Employment Levels but Many Are Not Backfilling Positions

Businesses report either not reducing their workforce in the last three months or doing so passively. Chart 4 shows that 56 percent of firms have not reduced their workforce in any way in the past three months. Those firms that reduced their headcount did so mostly through attrition and closing job openings without backfilling those positions. A relatively small share (11 percent) of firms indicate they have implemented selective layoffs over the past three months. Only a few firms (4 percent) indicate their headcount is falling due to hiring constraints.i These responses also align with declining worker hours—an additional labor utilization indicator—reported by a growing share of firms in recent months (External LinkKC Fed Surveys).

Chart 4: Most firms are keeping employment levels steady, but some are passively reducing headcount by not filling open positions.

Notes: Data are from the November 2023–25 Manufacturing and Services Surveys for Colorado, Wyoming, and New Mexico.

Sources: Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City and authors’ calculations.

Looking Ahead

Labor markets in the Rocky Mountain region are currently marked by slowing, yet balanced, job growth and wage gains. On average, businesses anticipate keeping their workforce steady in the coming year. While more firms are pursuing headcount reductions than in recent years, reductions have thus far occurred mostly passively. Still, employment in the region has less momentum going into 2026 than at this time last year. Whether regional labor markets will remain resilient and maintain the current balance in employment and wage gains or exhibit vulnerability to any new shocks next year remains an open question.

____________________

i From the survey question, “Over the last 3 months, has your firm reduced its headcount?” the no reduction category is a combination of firms that responded: “No, but we have reduced the number of open positions without filling them,” “No, but we have reduced hours (including operating hours, shifts, and overtime),” “No, we are maintaining our headcount despite some drop in demand,” and “No, and none of the other answers apply to us.” The attrition category is a combination of firms that responded: “Yes, we have not attempted to replace workers who have left the firm” and “Yes, and we have reduced the number of open positions without filling them.” The selected layoffs category comes from firms that responded: “Yes, we have selectively laid off workers.” The worker/skill shortage category comes from firms that responded: “Yes, we have attempted to replace departing workers but have been unable to do so.”

References

“External LinkThe Tight Labor Market in the Rocky Mountain Region is Showing Some Signs of Easing”. Greene, Bethany and David Rodziewicz. 2024. Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Rocky Mountain Economist, January 10.

“External LinkColorado’s Current Employment Situation Driven by Key Industries”. Munoz, Juan David, and David Rodziewicz. 2025. Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Rocky Mountain Economist, October 8.

Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City. November 2025. External LinkManufacturing and Services Surveys.

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City or the Federal Reserve System.