More than 1.2 billion people have joined the global economy’s middle class in the last 15 years. Even with an average annual income of about $10,000, these new members of the middle class are having a big effect, according to Nathan Kauffman, Omaha Branch executive at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City.

Kauffman, speaking to about 180 attendees at the 2015 Agricultural Symposium, July 14-15 at the Kansas City Fed, said a wealthier consumer, for example, is a more choosey consumer, one who, in turn, changes global food demand and environments.

Demographic Trends

Most of the increase in the global middle class is in developing countries, the near-term effect of which will be a decrease in the share of consumption by wealthier countries from an estimated 64 percent to 30 percent. This doesn’t mean there is a strain on production—global food supplies remain strong; however, there will be a future increase in consumer demand for specific foods and how food is produced and marketed.

Asia and Africa play a large role in the demographic change, according to Wendy Umberger, an associate professor at the University of Adelaide, Australia.

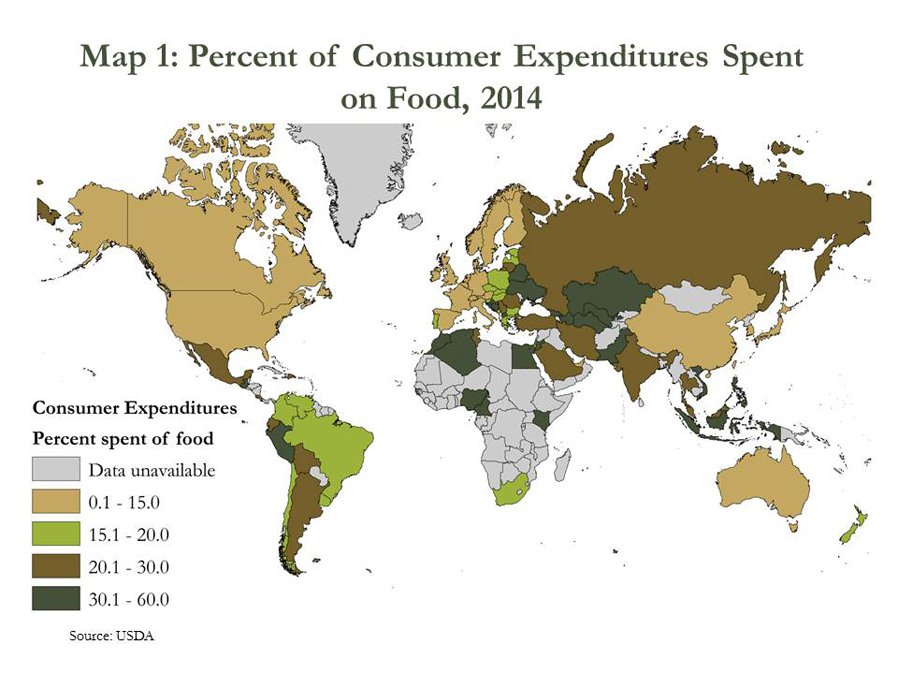

Umberger estimates there will be 2 billion more mouths to feed within a decade, especially in Asia, and says there could be a 70 percent increase in the demand for food as the middle class in emerging populations gains more disposable income (Map 1).

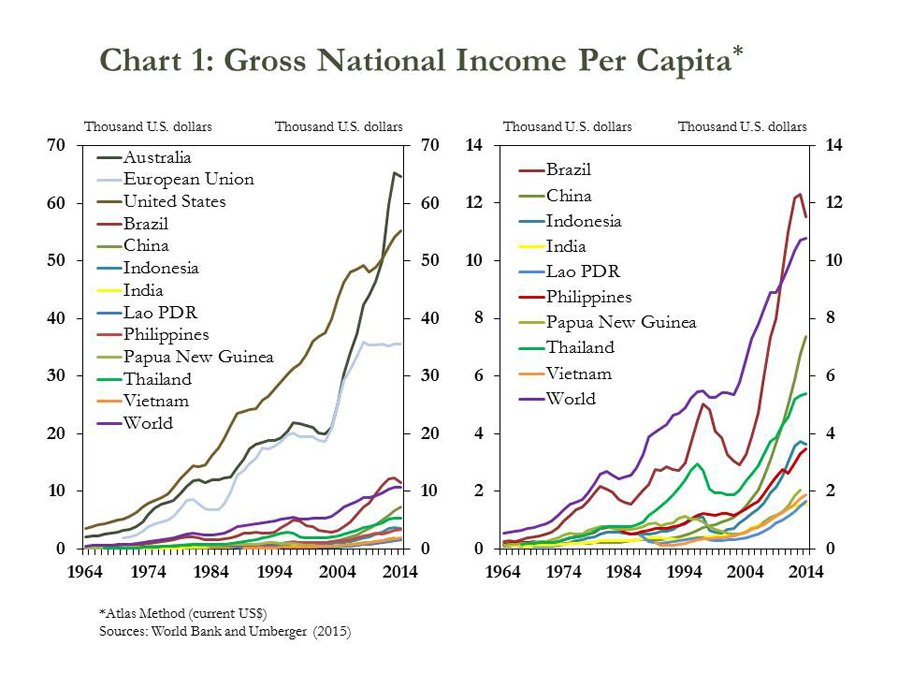

From 1990-2012, countries such as Brazil, China and Thailand have seen significant increases in disposable income. They’re not alone, Umberger said. Pakistan, India, Indonesia, Vietnam, Sri Lanka and other countries with growing urban populations have seen increases in disposable income among the middle class since the new millennium (Chart 1).

The level of disposable income among these countries remains well below wealthier countries, such as the United States, Germany, United Kingdom and Australia; however, the emerging middle class has begun to develop food preferences similar to consumers in wealthier countries.

Industries attempting to meet the varied demands of customers must understand consumers’ wants and purchasing needs. The changes mean consumers will place more attention on food quality and safety, production and distribution.

Consumer Preferences

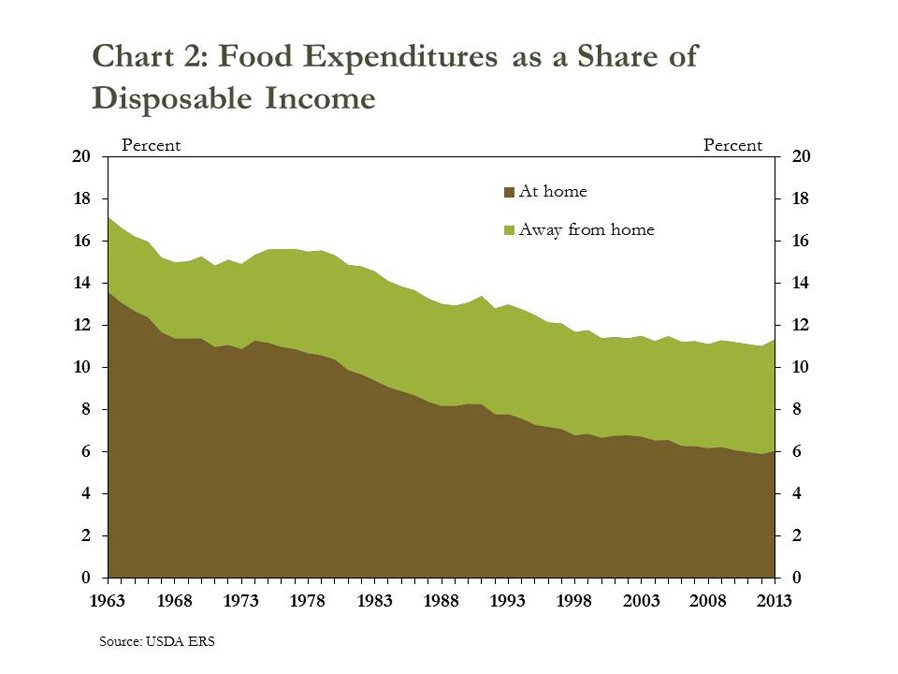

Today, U.S. consumers are spending more at restaurants and have cut home food expenditures over the last 60 years. This trend will continue for at least the next 10 years, said Bill Lapp, president of Advanced Economic Solutions (Chart 2).

“Consumers want more out of their food,” he said. “Not so much in calories but in expectations of quality and how food is produced.”

For instance, millennials believe they consume healthier, more expensive, more natural and less processed food than their parents. This attitude feeds into the growing trend of consumers being more mindful of how food is grown, processed and distributed.

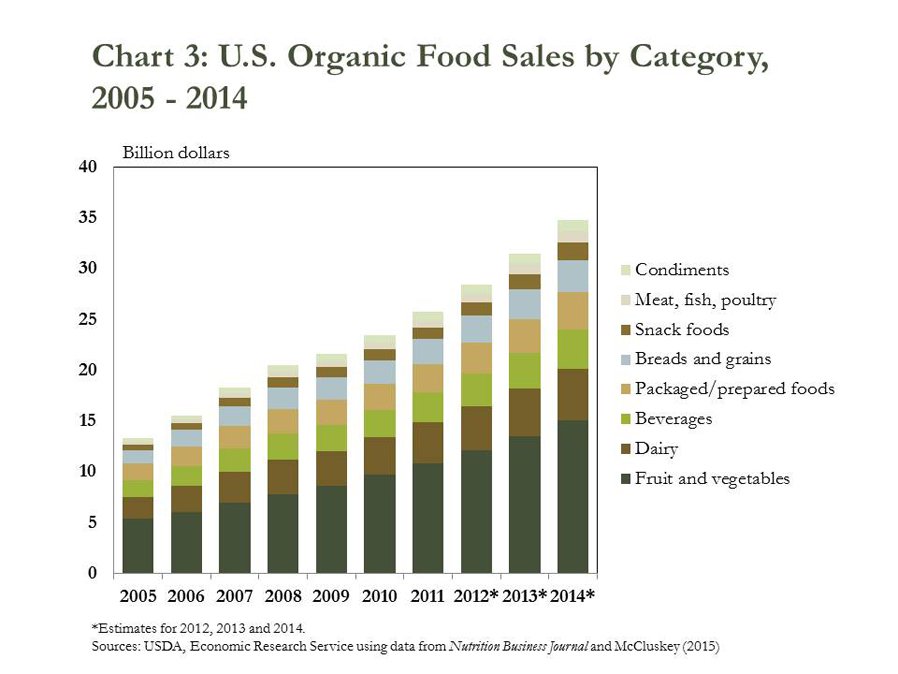

“Sustainability is an important factor in how millennials look at food purchases,” Lapp said. One result is an increase in organic food production, which is growing faster than other agricultural sectors, but still remains a small percentage of the market (Chart 3).

“Millennials are willing to pay more for food products produced in a more sustainable environment than previous generations,” Lapp said. “The industry is still trying to figure out what sustainability means.”

Globally, consumers also are willing to pay more for food products if it fits their needs, Umberger said. Today, consumers in developing countries have more choices —from open markets to conventional grocery stores to increased online buying, she said. They’ve also responded favorably to the introduction of food chains such as Starbucks, Dunkin’ Donuts and McDonald’s, which has altered nutritional values and consumption, Umberger said.

This doesn’t mean they’ve abandoned traditional food production, which trends toward organic food.

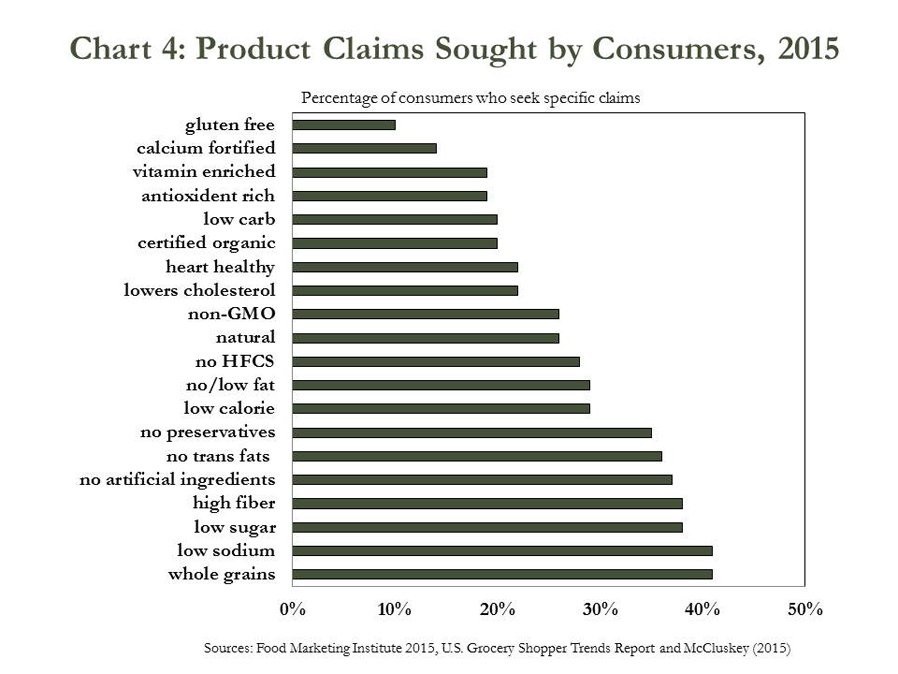

Jill McCluskey, a professor at Washington State University, said this is a sign of how consumers view food in relationship to their well-being. For example, younger U.S. generations identify themselves by what they eat (Chart 4). Foodies, aficionados and consumers wanting more from their food, have created a niche-driven food market, McCluskey added.

The result is more transparency in food production, said Bob Nolan, a senior vice president of insights and analytics for ConAgra Foods.

“The industry’s attempt to figure out these changing demands is ongoing,” he said. In some instances, the attempt has led to better food products, in others, it has created consumer confusion—a particular food viewed as healthy one year may be unhealthy for someone the next. And what consumers say and do are two different things.

For example, U.S. consumers have been on a health and wellness trend the past decade, yet we’re more obese as a nation, said Joshua Sosland, vice chairman of the Sosland publishing company.

“Consumers are changing, the culture is changing and it’s getting more difficult to capture food trends from a marketing standpoint,” Sosland said.

Domestic and Global Food Quality

Consumers are demanding certain foods every day, 365 days a year. That’s why it’s important that countries other than the traditional food producers, such as the United States and Australia, continue to grow their agricultural sectors.

“We are an interconnected system globally,” said Scott Portnoy, corporate vice president for Cargill Inc.

Although there have been improvements in the global food supply in terms of meeting demand and food safety, Portnoy said there is room for improvement, especially considering how many third-world countries have inadequate food production, safety and supply systems.

One of the hurdles is that food production and safety means different things to different cultures.

Julie Caswell, a professor at the University of Massachusetts, said consumers in industrialized nations have taken great interest in food safety and quality. That interest, however, hasn’t eliminated confusion among consumers. “Consumers have to rely on others to measure the quality of their foods,” she said.

For example, how much insecticide residue is left on food products? What are the nutritional values of certain additives? Although the United States heavily regulates food quality, consumers are frustrated about who actually regulates food attributes. And in some instances, it’s difficult to determine whether consumers, consumer groups, regulators or production companies influence regulatory changes.

The market around quality, however, doesn’t always work according to plan because there is a lack of information about food products in general, Caswell said. That’s why regulatory policy plays a large role in solving quality control issues, but sometimes the solutions are derived from consumer perception rather than science, Caswell said.

Robert Johansson, acting chief economist for the U.S. Department of Agriculture, says the emerging issues in regulatory policy are consumer food preferences, content and safety labeling issues, and food loss and waste. Another issue is how much of food production should fall under regulators or producers’ voluntary measures.

The industry is also focusing on the effect of global food demands on domestic and international production, he said.

Producing for a Global Market

Agriculture sits in the middle of some of the most complex problems in the world, from water conservation to feeding a growing global population. Science has helped the industry increase the quality and quantity of food, but the industry and consumers often focus on nonscientific information when making agricultural decisions, said Brett Begemann, president and chief operating officer of Monsanto Co.

Begemann says this has created confusion about food production and safety among consumers and the industry, which he attributes to either a lack of information or bad information.

“We need to allow science to drive more of our conversations,” he said.

Portnoy says the answers to issues of supply and demand, quality or sustainability may lie within several production methods, such as low-productivity organic agriculture and traditional high-yield farming.

McCluskey says production may evolve to match the growing trend of customization, where the culture and economy shift away from mainstream products and markets toward a huge number of niches. As customization becomes more efficient and innovative, and production and distribution costs fall, there will be less need to lump products and consumers into one-size-fits-all containers, McCluskey said.

The downside in this push to customization is low productivity, whether organic or sustainable farming, she said. And the question remains of whether customization, even if consumer driven, can meet the growing global demand for food.

That’s why Portnoy remains cautious because trends come and go and sometimes change in midstream. And with every trend, whether global or domestic, there are financial risks.

Financing Agriculture

Gene Moses, senior strategist for the International Finance Corp., says changing consumer preferences will provide greater finance opportunities globally. But with every opportunity come risks and rewards.

Ejnar Knudsen, a managing member of AGR Partners, says record profits in agriculture—booms—are usually followed by busts. For example, the rebound in U.S. agriculture’s profitability in the last five years suggested the industry had entered a new era.

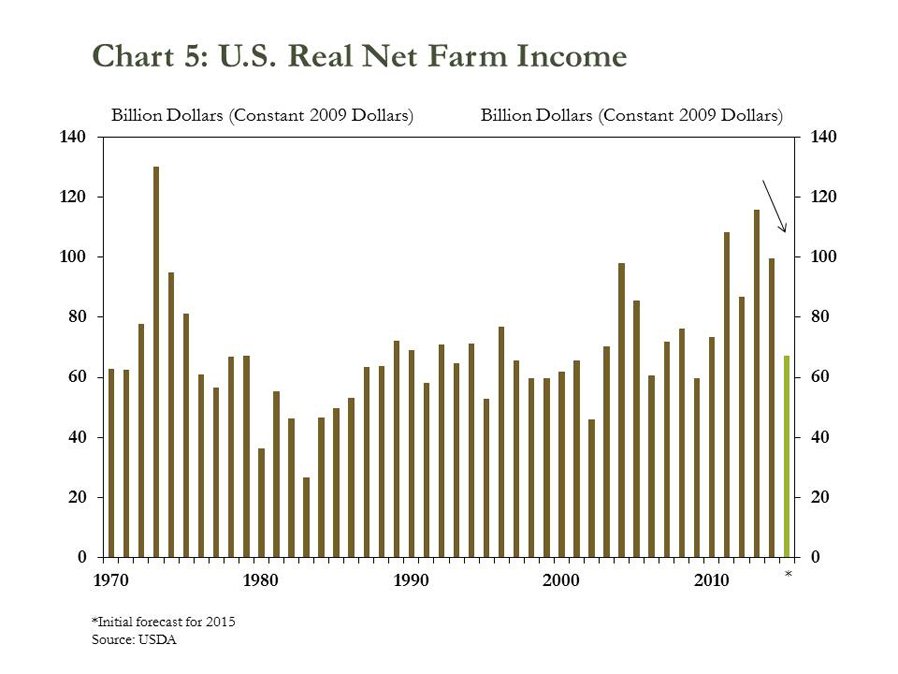

Michael Boehlje, a distinguished professor at Purdue University, pointed out, however, that despite changing consumer demands, U.S. aggregate net farming income is expected to decrease 30 to 40 percent in 2015 compared to recent years (Chart 5).

“The wealth increases of the last five years are coming to an end,” he said. “We won’t have a bust, but a soft landing.”

The risk is in becoming single-minded, said Michael Swanson, a senior vice president and consultant for Wells Fargo.

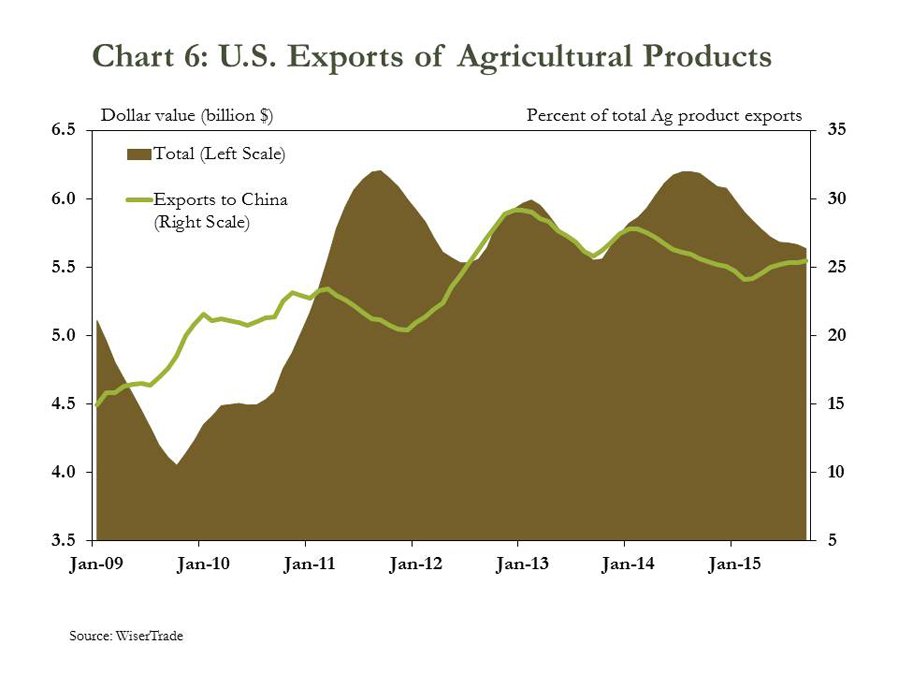

For example, China is the leading destination for U.S. agricultural goods. Unlike the United States’ other major trade partners, China purchases more bulk grains for livestock feed than processed foods. The risk involves the U.S. industry not being prepared for any type of disruption within China’s market, which could include a slower economy and the country’s middle class changing food preferences—shifting away from bulk commodities to more processed foods (Chart 6).

Knudsen says global consumer trends are where the demand-side risks lie. Not so much with the consumer but with the increase in global competition.

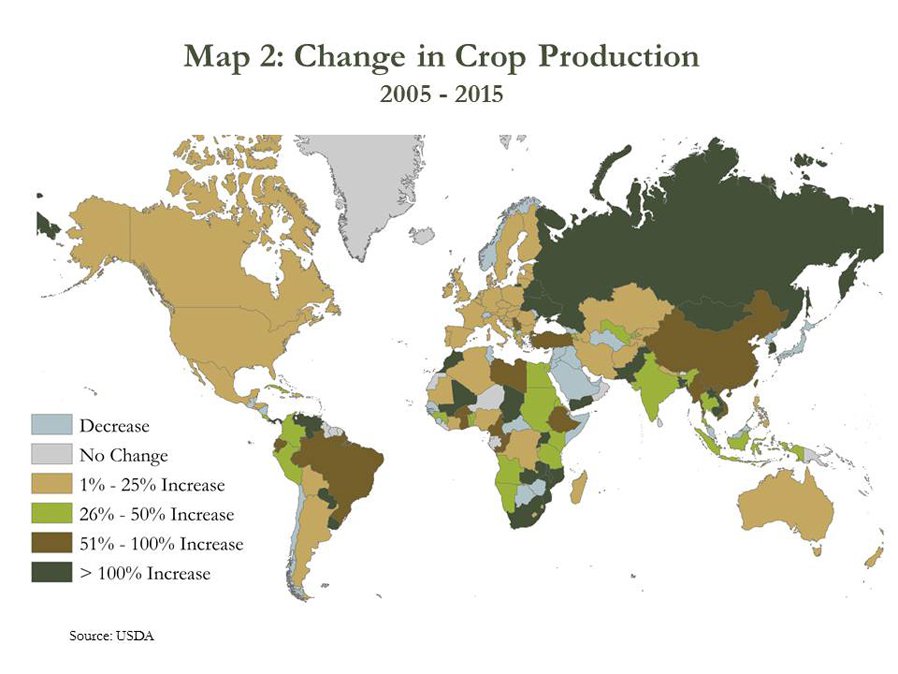

For instance, as the rising middle class has changed the demand for particular foods, Australia, Russia, Asia, South America and Eastern Europe are enhancing their production capabilities through the adoption of advanced agricultural technology and enhanced agronomic practices (Map 2). This effort is challenging the United States as a global food supplier.

With this environment of increased competition, finance should focus on the resilience of global innovation, supply chains, various values of products, production and demand, changing consumer preferences and growing incomes in emerging markets, and the evolving role of global agricultural traders, Moses said.

The world is changing and the traditional ways of agricultural finance will need to meet those changing needs, Moses added.