Foreword

At the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City we have produced a number of publications focused on historical explorations of several important banking-related topics including the founding of the Federal Reserve, a history of the payment system and the lessons from past banking and financial crises. We believe a knowledge of history can hold a key to understanding the current environment and is a necessary step in efforts to address some of our most difficult economic challenges.

In 2019, we published “Let Us Put Our Money Together: The Founding of America’s First Black Banks.” The book focused on the formation of the earliest African American banks and the important work of the institutions and their leaders in providing access to credit and financial services for a population who had been unserved and marginalized.

Our motivation was twofold.

In researching the role of community banks in U.S. economic history it was clear that the history of our nation’s African American banks was not broadly available nor widely known. We also believed that the publication was an important and meaningful contribution amid a continuing decline in the number of Black banks. The loss of these banks negatively affects communities and households, particularly those left to turn to the often-costly alternative financial services providers, such as payday lenders and pawnshops.

We quickly discovered there was significant interest in this topic. Many readers, in fact, encouraged us to expand our exploration of this history with another publication bringing the story forward. Within the Kansas City Fed, we felt similarly, believing a consideration of events that happened across a more extended timeframe would prove valuable in trying to resolve a problem where too often periods of progress have been followed by a loss of momentum and, as a result, inevitable setbacks.

Rather than providing a comprehensive history of Black banking, our goal here has been to move across time, examining some of the communities where banks played a dual role, fighting for both economic opportunity and social equality. Readers will find that the motivation to create many Black banks, regardless of the time period, was rarely a purely financial endeavor or business opportunity. Instead, many were created with a primary mission of public service. This focus on the community is similar to the motivation behind many of our nation’s small and mid-sized banks today. Community banks are the catalysts in helping families and individuals establish business, buy homes and pay for education that can open doors to opportunity. They are community leaders.

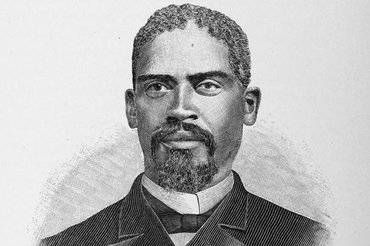

One example of this from the early history of our nation’s Black banks relates to the story of William Pettiford, founder of Birmingham’s Alabama Penny Savings Bank in 1890. Pettiford said in creating the bank he recognized that Birmingham had a large African American population whose earnings, after being deposited in a bank as savings, could be used as a source of credit for the city’s growing African American community. In later telling the story of the bank’s creation, he would often discuss something he had observed years earlier while serving as pastor of the city’s historic 16th Street Baptist Church. A husband and wife died leaving two orphan children. The couple’s estate of around $10,000 – more than $250,000 in modern-day amounts was lost because no one among the couple’s family or friends had the financial resources to post a bond that was required of anyone acting as administrator.’

“When I saw (the) helplessness to help orphan children in saving the property earned by their parents, it occurred to me that if we had a strong financial institution (we) could make bond and save the property left for the benefit of the heirs,” Pettiford said.

William R. Pettiford founded the Birmingham’s Alabama Penny Savings Bank in 1890.

We have drawn the title of this volume from a 1906 newspaper account of this event, which the reporter wrote “reveal(ed) the fact that a banking institution is sometimes a great moral and social force.”

That role is evident throughout this publication. Banks and bankers were and are centrally involved with some of the most important individuals and events in America’s history of race relations. Readers of our previously published history told us they were particularly appreciative of the way that book presented the social environment around the earliest institutions. With this volume, we believe it is even more important to place the histories of the institutions we examine within the context of their times given that economic opportunity is a necessary element in equal opportunity. Such context improves our understanding of these institutions while also potentially increasing understanding about how this history has shaped our world and continues to influence our communities in significant ways yet today.

For some readers, this inclusion of a contextual landscape will provide an introduction to historical events of which they may not have previously been aware. One example of this within the region served by the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City pertains to the establishment in America’s Plains of a number of Black towns, particularly in Oklahoma. Related to this, of course, is the painful story of the Tulsa race massacre, and the violent and horrific assault on that city’s Greenwood community in 1921, which is discussed here as well.

Greenwood Avenue was main street for Tulsa’s 35-block Greenwood neighborhood, one of the nation’s most vibrant Black communities of the early 20th century. By some estimates a dollar that came into Greenwood would circulate through 26 of its Black businesses before exiting back to “white” Tulsa.

America’s history of race relations is an often uncomfortable topic that includes many painful chapters. Some sections of this publication may be difficult to read. However, history shows that times of turmoil often intersect with banking and the central role of community banks in multiple ways: There were times when banks provided their communities with urgently-needed resources in the face of uncertainty; in other instances, racial tension and violence were catalysts for establishing a bank to serve the community. Notably, at key junctures in the fight for civil rights, bankers were among those leading the fight for social justice.

As I have seen firsthand throughout my nearly 40-year career, community banks are a critical facilitator of local stability and opportunity, and their influence extends well beyond the parameters of financial considerations. Many of the banks within this volume exhibit these qualities to an exceptionally high degree. Applying their lessons in the face of modern challenges has the potential to pave a path for progress.

Former President and Chief Executive Officer

Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City

Read a digital copy of A Great Moral and Social Force: A History of Black Banks. To request a complimentary hard copy of the book, External Linkfill out this form.