Chris Reichert has seen a significant increase in the number of ride-share clients in the Kansas City metropolitan area.

“I used to pick up mainly business-type clients—people needing a ride to and from the airport or someone on some type of business trip,” he said.

Now, his clients range from people needing a ride to and from the grocery store to young people from the suburbs traveling to the downtown entertainment district.

“Some of it is that people don’t own a car, or they’ve been out drinking and don’t want to get behind the wheel,” Reichert said. “Sometimes people don’t want to mess with the difficulty of downtown parking or don’t like driving at night.”

Reichert isn’t the only ride-share driver in the United States who has seen a sharp increase in customers.

The U.S. Census Bureau, which tracks the activity of “nonemployer firms” or freelancers, shows that 2015 saw the strongest growth of ride-sharing; figures from early 2016 show no signs of that growth plateauing as the industry moves into new metropolitan areas. Ride-sharing is becoming an alternative employment avenue in the transportation industry.

“The companies are growing and tapping into new markets all the time,” Reichert said. “It’s definitely becoming a legitimate business that I don’t see going away anytime soon.”

For Reichert, ride-sharing is a seasonal job. He’s a high school special education teacher and football coach in Lee’s Summit, Mo. His part-time job, however, has been profitable.

He tried Uber during spring break this year, and then continued to work for the company when he was out of school this summer. He added Lyft when the state of Missouri approved the company’s request to establish operations.

“I’ve done around 400 rides for Uber and about 70 rides for Lyft,” he said.

According to a report by SherpaShare, U.S. Uber drivers collected an average of $13.36 per ride and Lyft drivers collected an average $12.53 per ride in the first half of 2015. The company said it’s a national average and that costs vary by city.

For example, New York can average anywhere from $28 to $30, while in Denver the average is $11.

SherpaShare, a smartphone app that helps ride-share drivers track mileage and tax deductions, says fares are set in each city based on a formula using either a per mile rate or per minute rate. Fares can increase during high-demand periods. Although a gratuity is factored into the fare, passengers can tip extra.

“I could average anywhere from $15 to $30 in tips a night,” Reichert said. And full-time drivers could collect three times that amount, he added.

It’s the tax deductions that make ride-sharing a profitable endeavor, Reichert said. Ride-share drivers for Uber and Lyft use their own vehicles, which must be a newer model and in good condition. Drivers also must be at least 23 years old, have a clean driving record and insurance, and they must pass a background check.

Drivers who make ride-sharing their living can deduct such expenses as gas, car payments, mileage and insurance payments. Because Reichert works part time, he deducts the mileage of each trip from his taxes.

Ride-share companies also provide excess liability insurance. For example, Uber and Lyft provide $1 million in excess liability insurance per occurrence, and some drivers obtain gap insurance to cover travel between fares.

SherpaShare warns, however, to be careful about reading too much into ride-share numbers due to variables like bad weather, surge pricing, hourly guarantees and other special driver incentives that can skew the data.

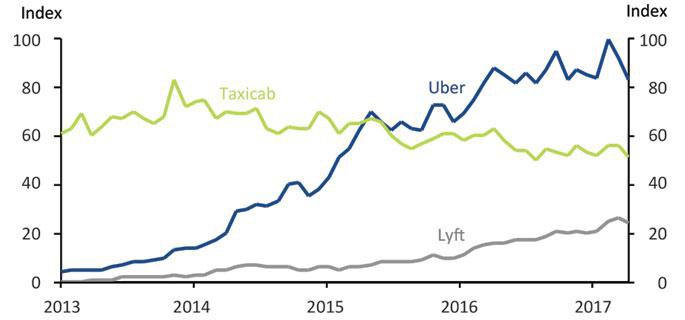

Google searches made by consumers for the major transportation platforms

Tracking the sharing industry

Michael Redmond, an associate economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, says economic data may underestimate the contributions of the sharing economy because the instruments used to measure economic activity have difficulty tracking this industry.

In his recent research, “Waiting for a Pickup: GDP and the Sharing Economy,” Redmond says growth in gross domestic product (GDP) has consistently fallen short of expectations since the Great Recession, making it the slowest economic expansion since World War II.

Redmond’s analysis suggests that correctly tracking the sharing economy could give a more accurate picture of GDP growth and the overall economy.

“The macroeconomic importance of this finding is tempered by the still-small scale of this (sharing) activity,” Redmond says. “But as ride-sharing and other dimensions of the sharing economy take hold more broadly, capturing their contributions will become increasingly important.”

Redmond explains that conceptually, measuring the output of the sharing economy is straightforward. Ride-sharing involves peer-to-peer transactions using internet-based applications. The matching of riders with drivers is similar to taxi services. Thus, Redmond says GDP accounting practices could measure ride-sharing as boosting the taxi services category of economic output; however, a significant portion of the economic value of the ride-sharing services appears to have gone unmeasured.

Google Trends, which measures internet searches, showed that Uber, the dominate ride-share service in the industry, grew rapidly in 2014 and continued to increase in popularity in 2015. Although Uber and even Lyft—at a lesser amount—began trending upward, GDP data showed spending on taxi services began to decline during that same period.

Redmond’s analysis shows, however, that there were measurement issues in taxi and ride-sharing services during this time. For example, between mid-2014 and mid-2015, overall rides provided by taxi services in New York City increased 17 percent while rides provided by taxi services nationally declined 12 percent. Thus, rapid growth in ride-sharing more than offset the decline in traditional taxi rides in NYC. At the same time, a Pew Research Center Survey showed that 15 percent of American adults reported that they used ride-sharing services during that time, which likely represents an overall boost to the broader taxi services market.

“But the data show taxicab services as a drag on real GDP growth instead, likely due to measurement errors that affect both the nominal estimate of activity in the sector and the price index used to deflate this measure,” Redmond said.

Some of the mismeasurement comes from the surveys used to track the taxi services market, Redmond says. These surveys, which show a decline in taxi services, are employer based, and don’t account for ride-share drivers, who are counted as individual proprietorships rather than direct employees of a company.

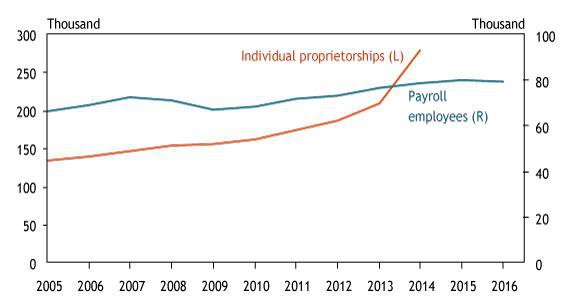

To back up this view, Redmond points at data for 2014 that show stagnation in the payrolls of taxi and limousine services amid a large increase in individual proprietorships. Redmond says this shows that ride-sharing is eating away at the market share of traditional taxi providers, which leads employer-based surveys to depress estimates of nominal taxicab service spending.

Another source of mismeasurement may result from relying on provider-specific prices to generate the price index. The price index does not take into account the decline in price from a consumer’s perspective when they switch to a lower-cost provider for the same service—such as switching from a taxi to ride-sharing, Redmond says. This oversight is known as “outlet substitution bias” and is well documented within the GDP methodology.

Although GDP measurements may not fully capture the ride-sharing industry’s effects on the economy, the result may have limited implications on the larger economy because the contributions of ride-sharing and other sharing services are small compared to the overall economy. For example, Uber drivers generated about $2.5 billion in U.S. revenue in 2015, while the overall U.S. economy was $18 trillion.

Redmond says, however, that as this segment continues to grow, it will become increasingly important to capture sharing services’ contributions to the U.S. economy.

Payroll employees and individual proprietorships in taxi and limousine services

Why sharing services increased

Industry analysts say the popularity of sharing services has grown because they are simple to use and provide customers options that traditional industries have made more difficult to obtain or use.

For example, a room at most resort destination hotels may cost hundreds to thousands of dollars per night, depending on location and the type of accommodations. Space-sharing platforms like Airbnb and HomeAway provide a cheap and convenient alternative.

Although the other sharing services such as money-sharing (Lending Club) and space-sharing have grown more than 50 percent in the last three years, according to industry data, ride-sharing has become the dominant force in this growing industry.

One development that has made all of this sharing work is improvement in technology, more specifically smartphone and tablet applications.

Clients can request a ride, a space or another service by using the app of the company that provides the service. For example: Each ride-share company has an app you download on your smartphone to use when you need to request transportation. A passenger uses the app to request the type of service they want and their destination. The app uses the GPS in a customer’s phone to find their current location and the nearest available driver. Once a driver is selected, the app displays the driver’s name, license plate number and route. Riders are able to track the driver’s location and receive a text message once they arrive. Riders can also rate drivers, providing other clients instant reviews of a driver’s customer service.

Although Reichert is new to the industry as a driver, he says convenience, personal connection and lower costs have all contributed to the industry’s growth.

“It puts it in the consumer’s hands, at their discretion, unlike a traditional taxi service,” Reichert said.For example, before consumers request a ride, they can get a quote by entering the pickup location and destination. The GPS on the customer’s phone tracks the distance of the ride to calculate the cost. Once at the destination, the credit card the customer registered or other form of payment is automatically charged and they receive an email receipt. They can also easily split the fare with other passengers—it’s all within the app.

Time will tell whether this convenience and lower costs have culminated in continued growth for the industry. U.S. Census Bureau nonemployer firm statistics for 2016 will become available in 2018. Analysts predict, however, that sharing services will have staying power and the sector will continue its overall growth. And it will contribute to other services and business in the process, and begin to have a greater impact on the national economy.

Further Resources

Read:"Waiting For a Pickup: GDP and the Sharing Economy," by Michael Redmond.

This article is from the third quarter issue of TEN.