The agricultural economy, both in the United States and internationally, continues to adjust to sharp drops in commodity prices and profit margins of just a few years ago. Those declines have led farm producers, agribusinesses and agricultural lenders to consider fundamental changes to their business models to maintain competitiveness, improve efficiency and position their businesses for long-term growth.

These decisions, however, require a pragmatic recognition of a new commodity-price landscape, resulting in strategic realignments and consolidation across the agricultural sector.

Whether it’s at the farm or retail level, realignment and consolidation in the industry is expected to continue for several years, said Michael Langemeier, director of cropping systems, Center for Commercial Agriculture, Purdue University.

Langemeier spoke at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City’s 2017 Agricultural Symposium, “Agricultural Consolidation: Causes and the Path Forward,” June 13-16 at the Kansas City Fed’s headquarters. Through keynote speakers and panel discussions, the symposium explored the underlying drivers of industry consolidation and potential implications for businesses, consumers and rural communities.Langemeier said three key things will emerge from agricultural consolidation:

- We will continue to see various farm sizes in the future.

- Larger farms’ production percentage in the industry will continue to increase.

- Farm consolidation will become a global phenomenon.

“When we talk about consolidation, we’re talking about moving from midsize family farm category to large family farm category,” Langemeier said. “Large family farms are a smaller part of the overall market, 4 percent, but have 50 percent of the production.”

This is a change from two decades ago, when large farms made up a smaller percentage of the market and only one-third of farm production.

Michael Boland says consumers will drive this consolidation, because they’ve been given more choices than at any time in history. He adds that technology has helped create what he described as a new industrial revolution on a global scale.

“People are delaying marriage, having less children, and don’t mind buying more perishable foods that they consider ‘natural’ or ‘organic,’” said Boland, professor and director of the Food Industry Center, University of Minnesota.

Consumers are now looking at how food is produced and how it goes to market.

“Consumers want less preservatives, less GMOs, clean labels, better production,” Boland added. “It’s easier for large food producers to make changes and adopt faster to meet consumer demand than a smaller operation.”

Changing consumer demands has altered the farming business model, said Pam Johnson, an Iowa farmer and former president of the National Corn Growers Association.

“Families aren’t getting out of the farming business, they’re becoming corporations,” she said.

Even today’s agricultural workforce has different demands and expectations—workers are more adaptable, educated and technology driven.

“It’s going to take educators, organizations and companies to learn how to do things differently to meet the demands of the new generation of ag industry workers,” says Jennifer Sirangelo, president and CEO of the National 4-H Council.

Johnson says this is why the industry must continue to think globally, especially as other countries continue to consolidate their agricultural industries and become stronger in the market.

“That’s why we must tell our story well and be competitive, not only in our industry but in the business market,” she said.

Richard Sexton, professor of agricultural and resource economics, University of California-Davis, says that although agricultural consolidation among producers will continue to increase, consolidation is even stronger among food retailers.

This consolidation has created powerful retailers that have started to eliminate wholesalers. For example, Wal-Mart, which is now the largest food retailer in the United States with 17 percent of the market, has become its own supply chain.

“These supermarket powers put in check any power the food manufacturers may try to display in the market,” Sexton said.

Online food retailers such as Amazon, however, could cut into brick and mortar sales and force supermarket powerhouses such as Wal-Mart and Kroger to enter the online marketplace on a more aggressive scale.

Although consolidation is an outcome of technological progress, consolidation also has helped drive technological advances. As farms consolidate, they need to produce more with fewer resources. This has pushed the industry, especially in the biological digital sciences, to develop new technologies that provide breeders and growers with productivity and sustainability, said Michael Frank, senior vice president and chief commercial officer, Monsanto Co.

Consolidation, production models and technological advancements are the result of market pressures in the industry, said Bob Young, chief economist and deputy executive director of public policy, American Farm Bureau.

Buyers imposing production practices on producers, however, shouldn’t change how farmers view the market.

“They’re providing a service; whether they’re selling poultry or crops, it’s still driven by demand,” Young said. “We need to make sure that in the future those services remain profitable, otherwise it won’t be sustainable.”

Profitability is a growing concern among agricultural lenders, said Allen M. Featherstone, department head and professor, Department of Agricultural Economics, Kansas State University.

“There has been some erosion in agricultural lending among commercial banks in the last 10 years; however, they still hold two-thirds of all ag loans,” he said.

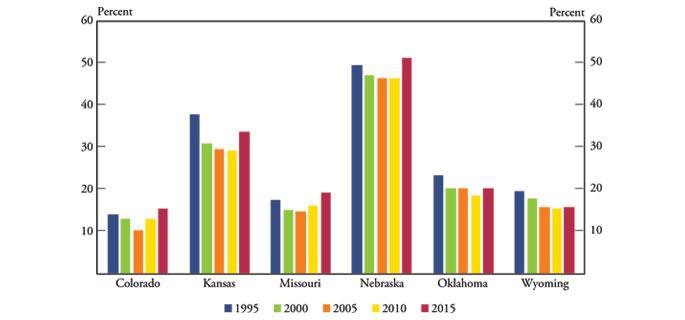

Average Agricultural Loans to Total Loans by Market Concentration

But lending could look differently in the future as more consolidation in the industry occurs, said Damona Doye, professor, Department of Agricultural Economics, Oklahoma State University.

Doye says consolidation has begun to change the way people think about the lender-borrower environment. For example, does farm expansion make owners think the small community bank can no longer provide them the amount of credit and services they need? It also could make smaller banks reassess the risk of lending to larger, consolidated farms.

“Can lenders make fewer, bigger loans? And do they have the working capital and the amount of credit these larger producers need?” Doye asked.

So far, Doye says she has seen loan volume increasing in the industry, but some banks are diversifying their customer base away from just providing ag-related loans. They also are expanding their services, such as providing insurance, investment opportunities and other nontraditional financial services.

Robert Keil, senior vice president and chief credit officer, Dacotah Bank, says this diversification is occurring industrywide.

“Only 40 percent of the loan portfolio of the 16 largest ag banks is ag related,” he said.

The ability to be creative, adapt and grow is key in the changing agricultural environment, whether you are a farmer, lender, processor or supplier, says James Richardson, professor of agricultural economics, Texas A&M University.

“We look at farming as manufacturing,” said Kip Tom, chairman, Tom Farms, and chairman, CereServ Inc. “We continually look and find new value-added commodities, meeting consumer demands, and managing our risks.”

Although consolidation will bring about changes in the industry, he doesn’t see it as a hindrance to production and growth.

“I’m still optimistic about agriculture,” he said.

Further Resources

View more information on the Kansas City Fed's Agricultural Symposium and agricultural research.