The Oklahoma City Branch of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City opened 100 years ago, on Aug. 2, 1920. Ever since, the office has been the connection between the nation’s central bank and Oklahoma’s communities and financial institutions. When the office opened, the still-new state of Oklahoma was recovering from a global pandemic—the “Spanish flu”—and was suffering from a sharp downturn in commodity prices, both similar to situations today. However, the state’s economy has changed considerably over the past century and likely will continue to change. This edition of The Oklahoma Economist analyzes the evolution of Oklahoma’s economy over the past 100 years and the near-term outlook.

A new Fed branch in a small place

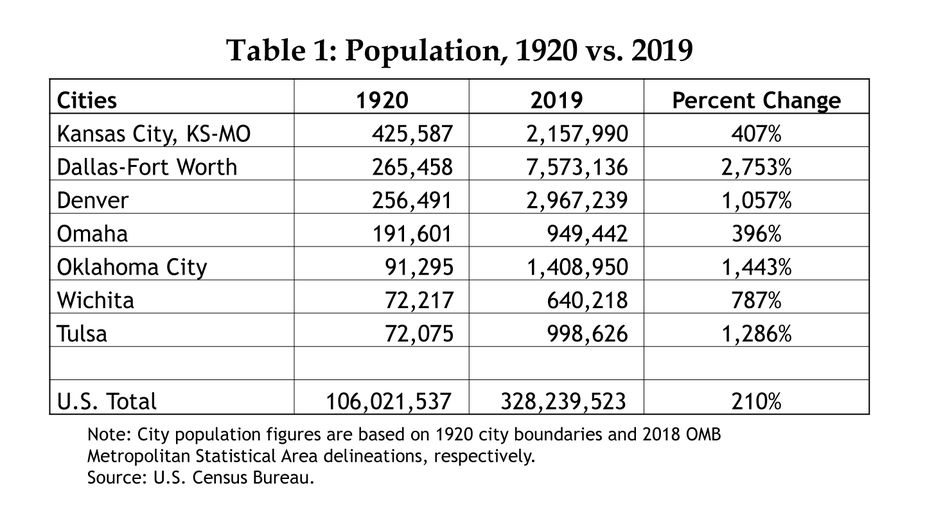

In 1920, Oklahoma’s population of 2 million was about half of what it is today. And its two largest cities—Oklahoma City and Tulsa—were much smaller then, with their primary counties having populations of less than 100,000 each, compared with respective metro populations of 1.4 million and 1 million in 2019 (Table 1).

Oklahoma’s population was characterized as only 25% urban in the 1920 Census, compared with 51% in the nation.

Other nearby Federal Reserve cities were much larger 100 years ago. Headquarters cities Kansas City and Dallas, where Federal Reserve Banks had opened in 1914, had considerably more people in their core counties than any place in Oklahoma. The two other branch office cities in the Federal Reserve’s Tenth District—Omaha (opened 1917) and Denver (opened 1918)—also had populations at the time over twice that of either Oklahoma City or Tulsa.

But bankers and communities in the southern part of the Tenth District sought a Federal Reserve office of their own, and in 1919 a competition emerged between Oklahoma City, Tulsa and Wichita, Kansas. Oklahoma City ultimately prevailed, as described in this history of the local Fed branch, largely due to the preferences of community banks in the state.

Today’s similarities to the Oklahoma of 1920

As in 1920, community banking remains important in Oklahoma in 2020. There were 883 banks when Oklahoma became a state in 1907, and while the number has dwindled over the past 100 years in both the state and the nation, an above-average presence of community banks continues today with over 1,300 locations across the state representing 185 distinct institutions. Their presence has been vital in 2020, in particular in serving as key connection between the federal government’s Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) and small businesses seeking to maintain their workforces and weather the pandemic.

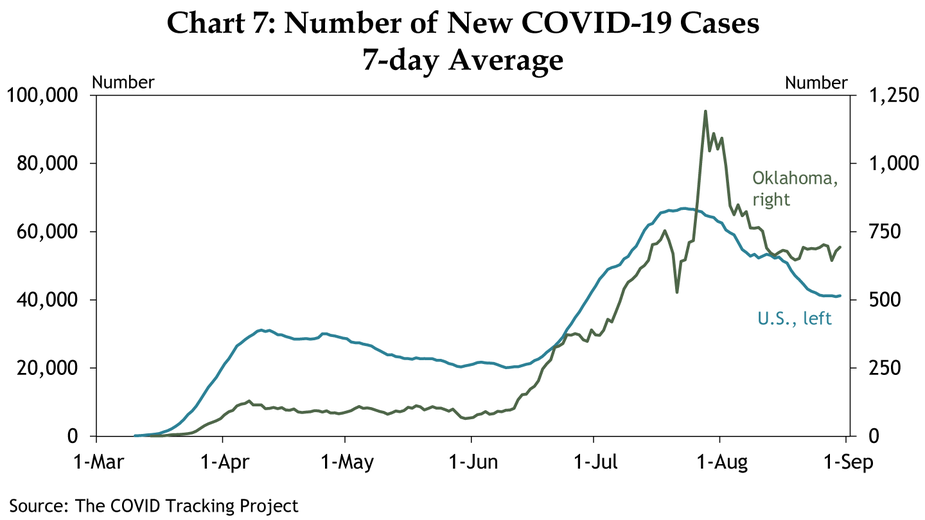

Another similarity with 100 years ago, of course, is the pandemic itself. In 1920, Oklahoma was just getting over the flu outbreak—which lasted from early 1918 through early 1920—killing 7,500 in the state and infecting over 100,000 people, or about 5% of the population._ So far, the deaths and cases from COVID-19 are well below those figures, but Oklahoma’s daily case numbers have been elevated since June and uncertainty surrounding the future path of the virus continues to weigh on the state’s and nation’s economies.

In addition, there was a crash in commodity prices in 1920, just as there has been in 2020. World demand for commodities dropped following the end of World War I, and reductions in economic activity from the pandemic further hurt prices. This year, both agricultural and energy commodities have seen a sizable drop in prices as world demand fell along with the virus. Despite some recent partial recovery in commodity prices, the challenging circumstances in these key sectors continue to weigh more on Oklahoma than the nation.

Key economic transitions in Oklahoma since 1920

While there are some similarities between economic conditions today with those of 100 years ago, Oklahoma’s economy has changed considerably over the past century. The kinds of work performed has shifted dramatically, in both the state’s economy as a whole and at the local Federal Reserve Branch. Oklahomans’ average incomes also have risen considerably relative to the nation since 1920.

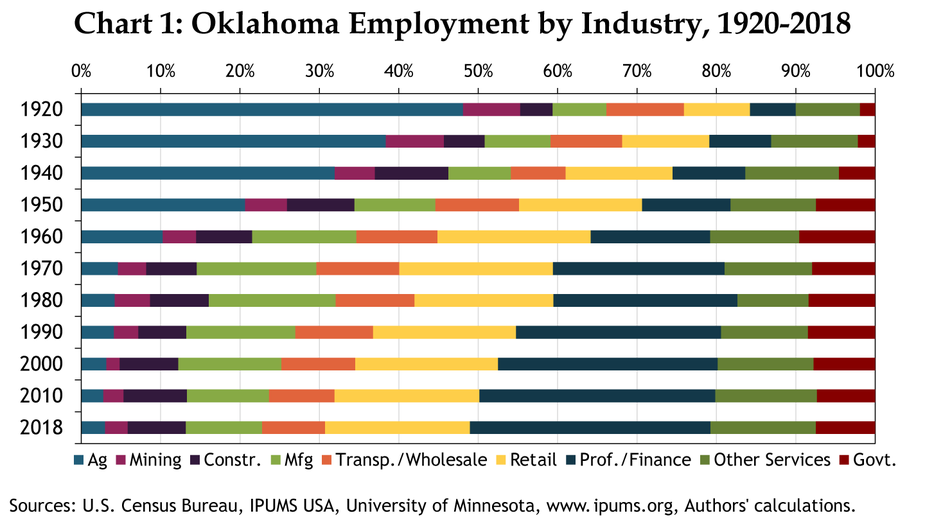

In 1920, over half of Oklahoma’s workforce was employed in agriculture or mining (including oil and gas), with the vast majority of those working on farms (Chart 1).

Most other sectors of the state’s economy were relatively small a century ago. By 50 years later—in 1970—agriculture and mining’s share of jobs had dropped to less than 10% of Oklahoma’s workforce, as productivity in those sectors grew tremendously and work in the manufacturing, retail and professional and financial services sectors became more plentiful.

Since 1970, the state’s industrial structure has continued to evolve. Agriculture and mining’s share of the workforce shrunk further after the commodity bust of the 1980s and has risen only slightly since then, as productivity enhancements in those sectors have continued to allow more work to be done with fewer workers. The state’s manufacturing workforce also is a much smaller share of overall employment, as productivity and globalization in that sector have grown. Meanwhile, most services industries—especially professional and financial services—have continued to expand, as the state has become even more urbanized.

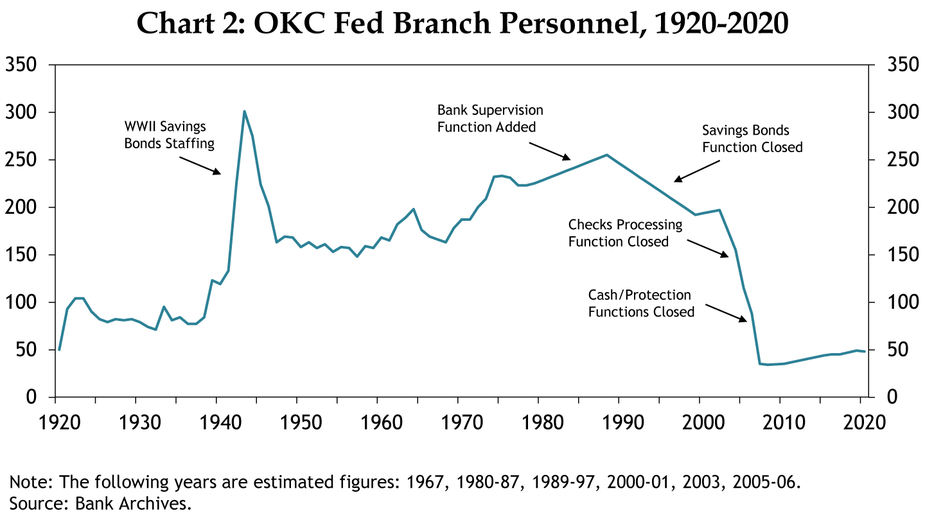

Employment at the Federal Reserve’s Oklahoma City Branch has mirrored some of these larger trends over its 100 years of existence. While both “blue collar” and “white collar” work always has been done at the office, the mix has changed over time. For much of the branch’s history, a majority of the workforce was employed in more manufacturing-type activities like cash vault operations and the processing of paper checks and savings bonds (Chart 2).

But as technology and productivity in those operations grew and consumer preferences changed, the number of employees in those functions shrank. Meanwhile, more services-oriented work in bank supervision, economic analysis, public outreach, and work with low income and minority communities became more prevalent.

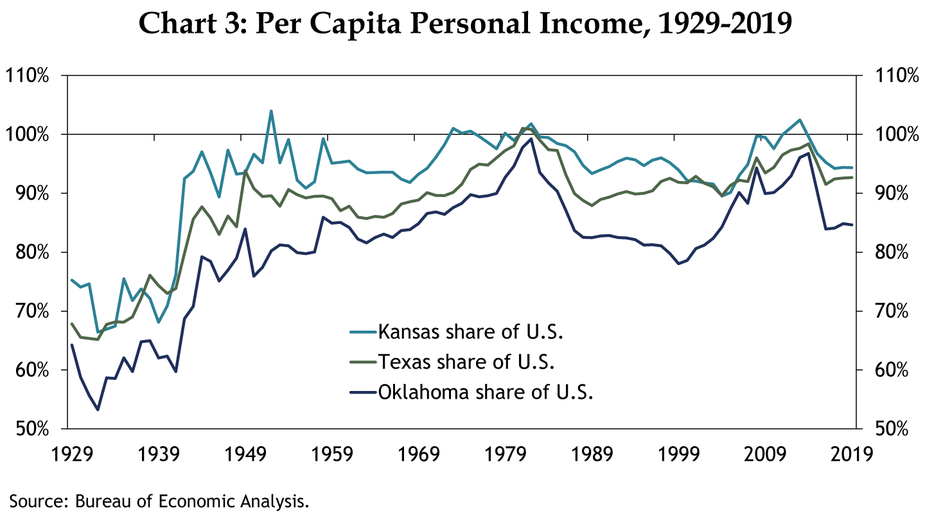

This shifting of industries and occupations in Oklahoma over time generally has been positive for average incomes in the state. Per capita income in 1929, the earliest year available, was just 65% of the national average (Chart 3).

And just a few years later—in the depths of the Dust Bowl and Great Depression—it had dropped to barely more than half of the national average. But as work in the state shifted from agricultural production toward manufacturing and then services activity—even while maintaining a sizable presence in the oil and gas industry—Oklahoma’s per capita income by the early 1980s nearly matched the nation.

Since then, trends in the energy industry generally have dictated the gap between per capita income nationally and in Oklahoma. Just prior to the drop in oil prices in 2014-15, Oklahomans’ average income once again neared the national average—just as it had in 1981—before losses in energy jobs and incomes drove it lower. Since 2015, the state’s per capita income has lagged about 15% behind the nation.

Outlook heading into OKC Fed Branch’s second century

Overall, the 100 years from 1920 and 2020 were positive for Oklahoma’s economy. Despite sizable challenges in the state during the Great Depression of the 1930s and the oil bust of the 1980s, Oklahoma’s population and per capita income increased over the past century. Looking ahead, however, some near-term challenges must be overcome before solid growth in Oklahoma’s economy and per capita income can resume.

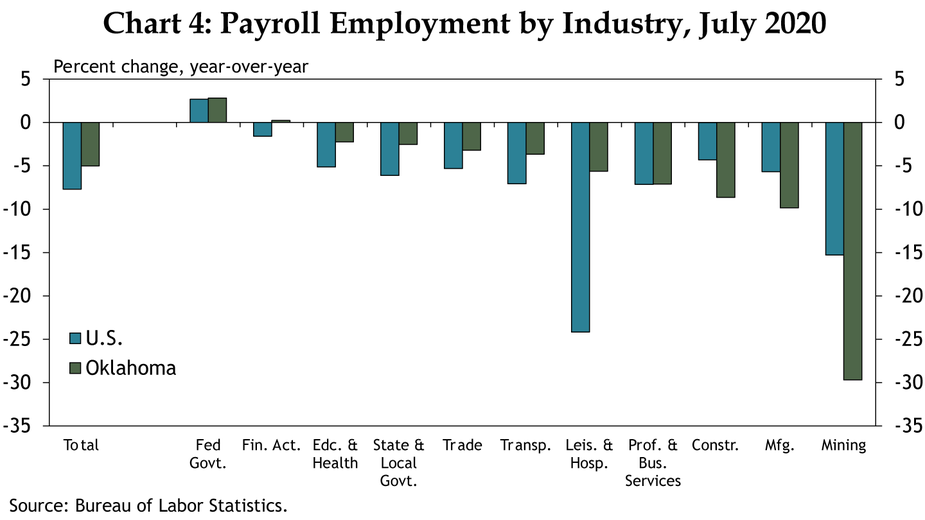

So far in 2020, Oklahoma’s employment is down about 5% from last year, and unemployment in the state rose above 7% again in July (Chart 4).

Mining (almost completely oil and gas-related in Oklahoma) has been the hardest-hit industry, with jobs down nearly 30%. Jobs in the manufacturing, construction, professional services, and hospitality industries were also down more than 5% through July, as demand from both businesses and consumers dropped following the shutdowns and caution wrought by the coronavirus.

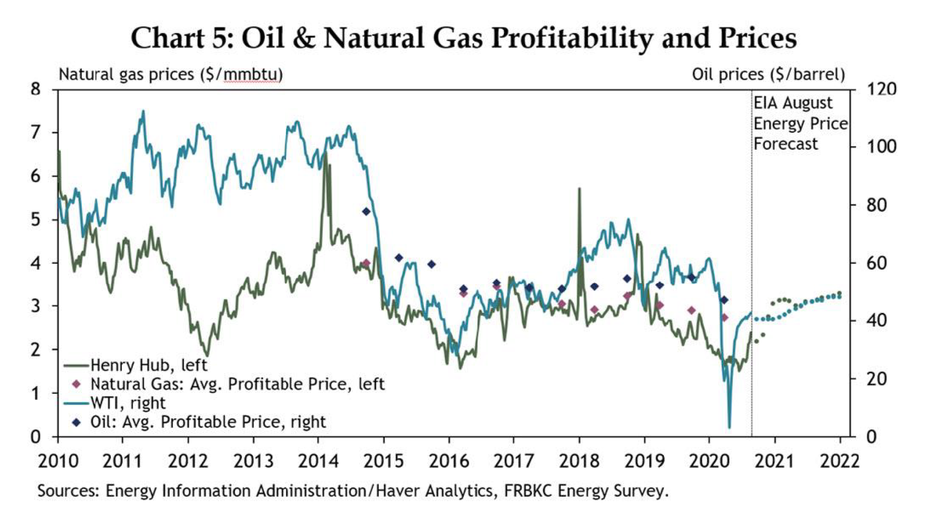

As noted in previous editions of The Oklahoma Economist, energy activity in the state already was falling prior to COVID-19. Given that firms pulled back on energy activity in Oklahoma before other places, any recovery in the sector is likely to lag that of the nation. While both oil and natural gas prices have moved closer to what firms say is the level needed for profitability, neither oil nor gas prices are expected to move above those levels in the immediate future (Chart 5).

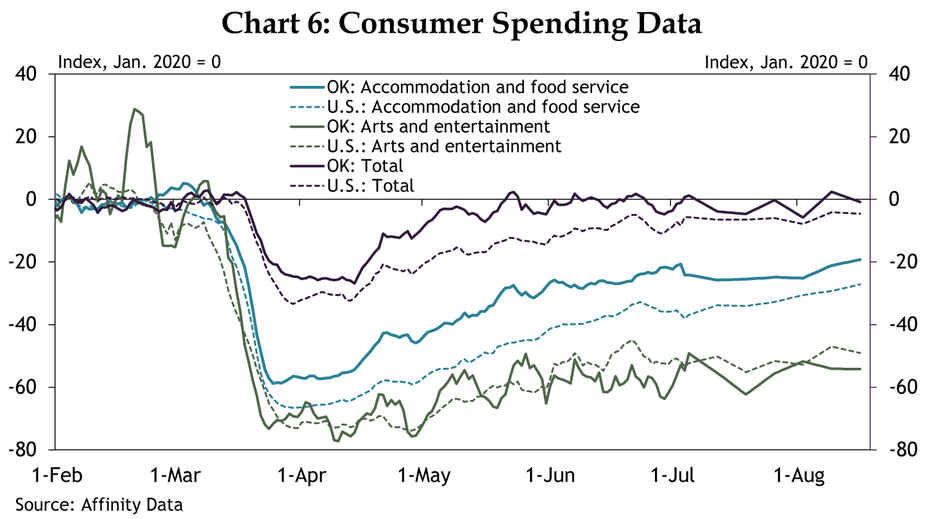

In other sectors—especially those affected most by virus-related shutdowns and caution toward exposure—full recovery also seems unlikely to occur in the near term or until the virus is contained. Overall consumer spending in the state through mid-August had returned to near levels from earlier in the year, but hospitality and tourism-related spending still was down considerably (Chart 6).

More spending on food at grocery stores and spending at general merchandise stores has pulled total spending up close to normal. While the daily number of new COVID-19 cases in Oklahoma has fallen somewhat from the high numbers of late July and early August, new cases remain elevated and higher than in the nation on a per capita basis (Chart 7).

Summary

The global pandemic, high unemployment and low commodity prices may inhibit near-term growth in Oklahoma’s economy. But the state has weathered a variety of challenges and changes over the past year, from commodity busts to increased urbanization—and is likely to weather these as well. Throughout the past century, the Oklahoma City Branch of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City has played an important role in Oklahoma’s economy, and can be expected to continue to adapt as needed to best serve Oklahoma’s communities and financial institutions.