Through borrowing, many Americans are able to finance an education, establish a business or purchase a home…For the first African American banks, it was not only about serving as a source of credit for businesses and consumers, but also about providing training opportunities and jobs for African Americans, supporting economic development and, importantly, pride.

-Esther L. George, president and chief executive officer of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City

This digital exhibit is based on the book Let Us Put Our Money Together: The Founding of America's First Black Banks by Tim Todd. Request a free copy of the book be shipped to you and to watch an interview with the author.

Though essential to form economic stability and financial success, Black Americans were legally unable to access credit and services through established banks before 1868 when the 14th Amendment gave citizenship and “equal protection of law” to all people born or naturalized in the United States. Because Black Americans were barred from accessing the financial system through traditional banking institutions, they were forced to make their own inroads to economic opportunities like borrowing and lending money. Through free Black business leaders and their connections to white intermediaries or accommodating bankers, Black communities and individuals were able to receive their first lines of credit. These individuals were operating in the North before the Civil War, the emancipation of slaves, or the 14th Amendment and helped to pave the way for the Black owned and operated banks of the twentieth century.

The Earliest Lenders: Before Emancipation

Stephen Smith

Stephen Smith was introduced to the lumber business while he was still a slave in Columbia, Pennsylvania in the early 1800s. After buying his freedom at age 20, Smith started his own successful lumber company that made ventures into real estate, banking, and personal lending possible. It is said that Smith was the largest stockholder in Columbia Bank, yet due to his race, it was illegal for him to be president of the bank. Despite this, Smith worked tirelessly to advance the Black community as a personal source of credit and as a voice for equality in the banking sector.

Samuel Wilcox

Samuel Wilcox opened S.T. Wilcox Fancy & Staple Groceries in Cincinnati, Ohio in 1850. When asked why he chose to open a grocery Wilcox said, “I might have bought a farm and lived on my money, but I wished to show, if I could, that colored people could do something besides being barbers.” Eventually S.T. Wilcox became the largest wholesale grocery in Cincinnati and Wilcox opened other groceries in New York, Boston, and Baltimore. As a Black American business man, Wilcox knew the pervasive inequality of the banking sector, so he used his profit to buy stock in banks “so that there might be one colored man there to vote.”

Deposit book from Freedman’s Bank. (Courtesy of the Avery Research Center for African American History and Culture, College of Charleston, Charleston, SC, image e1526402912464 (circa 1867))

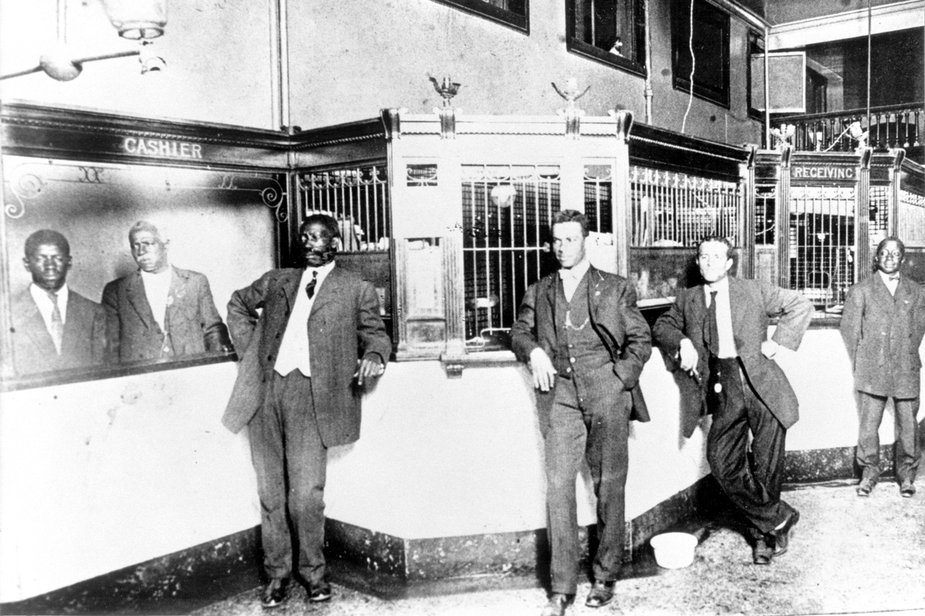

The Freedman’s Bank

While private lenders were able to help many free Black Americans, they were limited in the financial services they could provide. This was amplified after the end of the Civil War as Black soldiers needed a place to deposit their earnings. The solution was Freedman’s Savings and Trust Company created by an act of Congress in 1865. Headquartered in New York City, New York, Freedman’s eventually operated 37 branch locations across the South. At its peak, the savings institution held over 70,000 accounts. While Freedman’s held deposit accounts, it did not offer its customers lines of credit nor was it created with Black leadership.

Unfortunately, Freedman’s suffered from serious instability due to its mismanagement and over investment in high-risk loans. In 1874, Freedman’s officially closed. More than half of the bank’s 61,000 depositors are believed to have lost all their money in the failure. The largest deposit recovery – 62 cents on the dollar – was received by less than one-third of account holders and only after a period of several years. For many Black Americans, the corruption and failure of Freedman’s fostered feelings of betrayal and distrust of the banking system for years to come.

Picture of Fredrick Douglass. (Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, image LC-DIG-pga-07719, by Moss Engraving Company, N.Y. (1884))

Fredrick Douglass

In 1874, Frederick Douglass was asked to become president of Freedman’s Bank with the hope that his noteriety would keep depositors from withdrawing their money. “I could not help but reflect on the contast between Frederick the slave boy, running about Col. Lloyd’s with only a tow line shirt to cover him and Fredrick – the president of a bank,” Douglass wrote. After only six weeks, Douglass realized that Freedman’s was going to fail and that his personal loan of $10,000 would barely touch the deficit. Douglass later reflected on the men who created Freedman’s saying, “We have been injured more than we have been helped by men who professed to be our friends.”

The Alabama Penny Savings Bank. (Courtesy of the Birmingham Ala. Public Library Archives, image m-6281 (early 20th century))

The First Black Banks

Despite the services provided by private lenders and Freedman’s, the majority of Black Americans still struggled to find equal economic opportunities in the years following the Civil War and Reconstruction. It was from churches, fraternities, and mutual aid societies that America’s first Black owned and operated banks began. Between 1888 and 1890, The Savings Bank of the Grand Fountain, United Order of True Reformers, Capital Savings Bank, and Alabama Penny Savings Bank were established. Each was particularly resilient during a difficult time for the United States economy. While hundreds of other banks closed nationally during the banking panics that plagued America between 1893 and 1895, these banks survived and led the way for many others. Between 1899 and 1906, a second generation of 33 additional Black banks were established in the United States.

William Washington Browne: The Savings Bank of the Grand Fountain, United Order of True Reformers

Maggie Lena Walker, St. Luke’s Penny Savings Bank

Born to enslaved parents in 1864, Maggie Walker was raised in Richmond, Virginia. At only fourteen, she became part of the Independent Order of St. Luke, a social aid society, where she was eventually elected executive secretary treasurer. In 1903, Walker chartered the St. Luke’s Penny Savings Bank in Richmond, making her the first female bank president in the United States. She employed women of color and advocated for them to save money and make sound investments like home ownership. “We are Negro women,” Walker said, “…and we must make history as Negro women and make such history as will cause posterity to rise up and call us blessed.”

Maggie Lena Walker. (Courtesy of the National Park Service, Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site, MAWA 99-0780 (circa 1905 – 1910))

The Legacy

In recent decades, Black banks have been considered more broadly alongside other Minority Depository Institutions (MDIs) that are governed by or serve a racial or ethnic minority group. While these community banks still struggle to compete with larger banks, they play an important role in the national economy. MDIs serve the most economically challenged and vulnerable communities in the United States by providing financial services to underbanked populations. Today, roughly 55 million people or 25% of American households are under or unbanked. Black Americans are burdened by this inequity more than most as one in every five Black households is unbanked and one in every three is underbanked.

Access to credit through a trusted financial institution is as essential to personal and national economic growth today as it was when the first Black banks opened more than a century ago. Maggie Walker’s words still ring true. “Let us put our moneys together, let us use our moneys; let us put our money out at usury among ourselves and reap the benefits ourselves. Let us have a bank that will take the nickels and turn them into dollars.” MDIs carry on this legacy by working to provide diverse and equal economic opportunity for all people.

Minority Depository Institutions Today

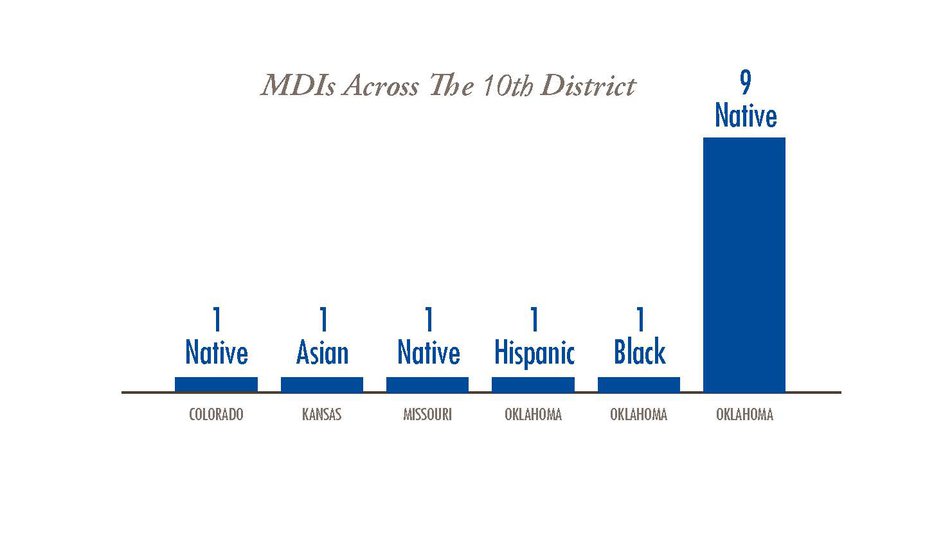

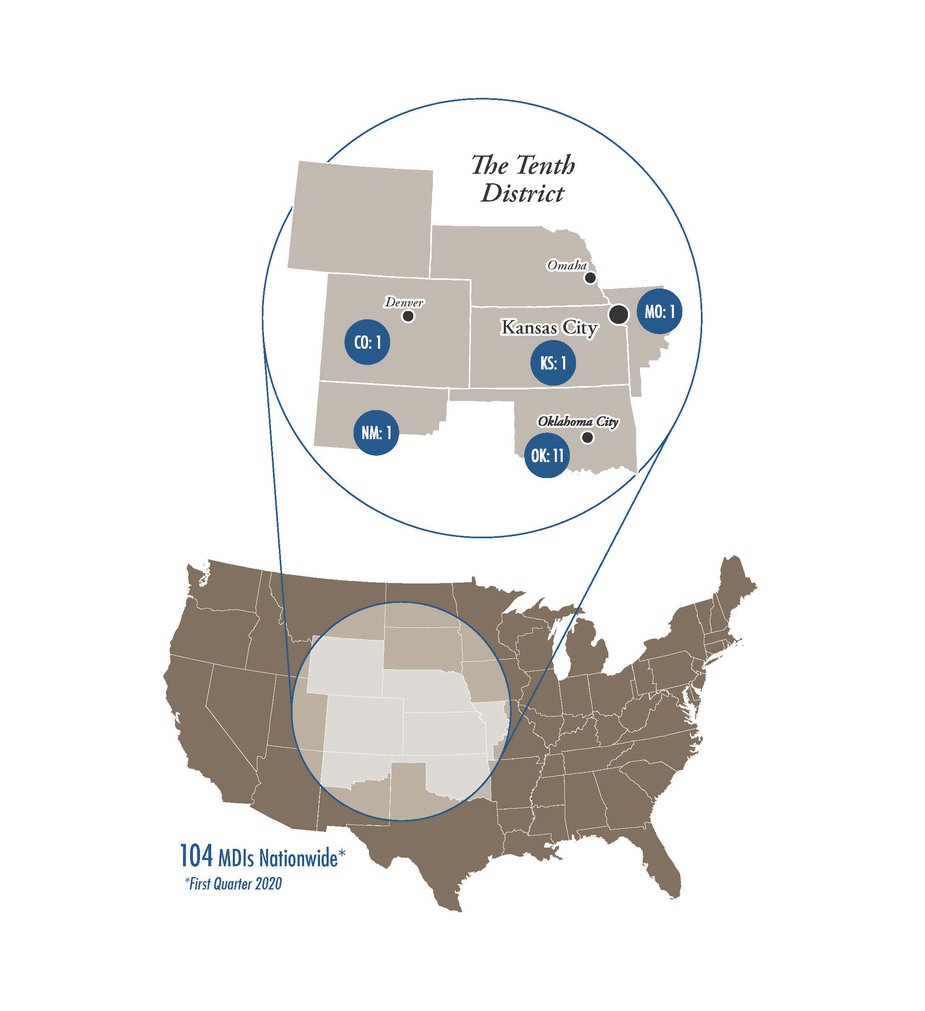

Over 100 MDIs are in business across the United States today, helping strengthen their economies. In the 10th District, fourteen Minority Depository Institutions provide a unique connection to their local communities and ensure that everyone, especially minorities, have quality access to credit and banking services. The Tenth District MDIs represent Native American, Asian American, Hispanic American, and Black American communities.

More information

Visit our economic education website to download a free copy of the accompanying lesson plan.

Progress through Parity: How Minority Banks Changed the Financial Landscape