“Students in (small-town and rural) areas aren’t learning about the mainstream economy by osmosis from friends and neighbors. They need explicit teaching: about the difference between dead-end jobs and multi-step careers, about how people make a living in their own towns and in big cities, and about how successful people constantly upgrade their skills. Ultimately, students need to know that the economy constantly changes and that everyone, no matter how well educated, must be alert to trends in the demand for skills and try to stay ahead of events.”

Paul T. Hill, “External LinkA better future for rural communities starts at the schoolhouse”

Some teachers teach traditional subjects like English or algebra, and some teach classes that could be classified as “adulting,” those that help students prepare for life after high school. Take, for example, classes that help students choose a career path. This summer, the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City conducted a free professional development webinar series for K-16 educators, offered in partnership with the Center for Economic Education at Emporia State University. Three of the six webinars helped teachers prepare students for a workforce in transition.

The webinars offered analysis of employment trends, the latest news in apprenticeships, and tools and resources teachers could use to help students choose a career pathway. They featured presentations from the Federal Reserve Banks of Kansas City and Philadelphia, the Ewing Marion Kauffman Foundation, Grand Island Public Schools, New America and the DeBruce Foundation.

What helps rural or small-town students plan a career?

A few weeks later, three instructors shared their experiences in helping students broaden their view of work, and how the webinars have helped. The three are:

Shirl Nichols

The business teacher at Smithville High School, a town of about 10,000 on the outskirts of the Kansas City region, teaches personal finance, intro to business, entrepreneurship, business management and business law.

Jose Ramon Rivera Acosta

He teaches developmental math, geometry, calculus, economics and personal finance at Yuma High School in Yuma, a rural community of about 3,500 in the northeast corner of Colorado.

Joy Rhodes

The former high school teacher is a family and consumer sciences/4-H educator for Oklahoma State University Extension in Garfield County, which includes Enid, and has a population of about 61,000. She teaches financial and homebuyer education, job readiness, and works with alternative schools.

Gigi Wolf, senior economic education specialist for the Kansas City Fed, led the conversation via Zoom. (Comments have been edited for length and clarity.)

Gigi: What did you most look forward to sharing with your students from the webinars?

Shirl: I always appreciate knowing anything about the job market. I use that information in two classes. In personal finance, they build a budget. It’s very important for them to do a lot of career research, so they build the budget based on what that looks like. The information shared is research-based, and that has a lot of impact on students. And for introduction to business, they figure out their personalities and what careers they would enjoy as grown-ups. I think our public education system has a void there, with too many students graduating without knowing what they want to do.

Joy: Looking at different careers and what the job prospects are for the future. This is a very rural area. I worked with a group of students, and they had only thought of two or three careers that they could even do in the area. I showed them that there are other things out there, and don’t limit yourself to just what you see in the community.

Jose: I teach a class called “employability,” which is required for graduation. The workshops gave me a lot of information and resources I need for the class, which helps them prepare for their future. For example, we are a very rural community, but there is a spaceport being planned for Bennett, not far from here. So all of the engineering and technical work made a combination that resounded in my ears about how I could move them toward an opportunity. Even though most of them want to be in agriculture, there is not a place for everyone in agriculture

Gigi: What do you think will resonate with your students the most?

Shirl: The idea that there is a lot more breadth and depth to jobs than the four they know when they come in the classroom. At 14, it’s what Mom and Dad know, and doctor, engineer, teacher and farmer. It’s a very thin concept of the job market. I was able to show them the different resources you provided and the breadth and depth of jobs that are out there that even I didn’t know about and the kids for sure don’t know about.

Joy: I agree. One town in my county had a lake and three different entities that run the lake. But all the students could see was the bait shop and the restaurant. You know, there’s the game rangers and the Corps of Engineers and all these other jobs that are out there that they just don’t see. So if you love to work outside all day, game ranger would be a great job.

Gigi: What content from the webinars do you think the students will be most likely to take and apply?

Jose: The option to do the research around those jobs and how they can base their research in the labor studies. It means that students can figure out the opportunities around here or wherever they want to move.

Joy: I agree. By moving toward an opportunity, then looking at the research and the job possibilities in the future, it makes a huge difference in their plans.

Shirl: A twist I would add relates to the session about students thinking they want a certain career, going down that educational path, then doing an internship. Then they’re 23 years old going, I don’t want to do this. I ask all of my students to each do at least a two-hour internship or apprenticeship in three different careers. I have had several students say, thank you so much. They say things like, I realized I don’t want to be an accountant, or I don’t want to sit there all day for eight hours. And I’m really proud to report, I had one student who shadowed an economist for a two-hour block. That student is now at Stanford in the economics program. So I’ve had extremes happen, but it has been very, very valuable.

Gigi: What about you, Joy or Jose? Did either of you find the information about apprenticeships helpful?

Jose: The information provided in the seminar really opened my eyes. Our school has done apprenticeships, but the examples in the webinar, those apprenticeship programs are better organized than at my school. I would like to encourage our school to offer apprenticeships that are more guided.

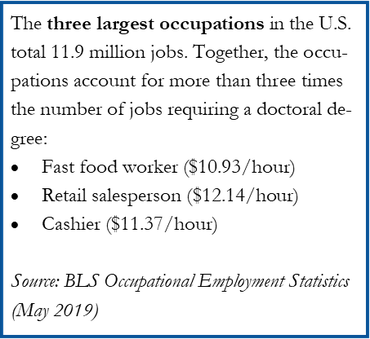

Joy: What I found helpful was information about good jobs you don’t need to have a four-year degree to get. Oklahoma has a very strong career tech system, a lot of which is geared toward computers. We’re kind of getting away from apprenticeships in jobs like plumbing, electrical and carpentry, but I really feel like that’s a very important area, job marketwise.

Gigi: Do you see a big emphasis on getting a four-year degree? If you do, how could what you learned during the workshop have an impact?

Joy: Yes, there is a big emphasis. The research that the Federal Reserve conducted on the future job market and earnings for particular careers shows students you don’t have to invest $150,000 in a four-year degree.

Shirl: I’m pretty blunt. I’ll put resources on the screen sometimes when students are walking in. I ask them, have you thought about being debt-free and making this salary? Here’s a video about this career path. And then the kids who are sitting right there who take that path, I’ll give them some accolades instead of the kid who’s getting the perfect ACT score and taking all the AP classes. That is so talked up in my school that I just directly combat it with other kids with other interests who are going to do just as well.

Jose: In our rural community, many of the parents don’t understand why students do or don’t need to go to college. Also, we have a very large immigrant population who work in the farms and in the fields, and they don’t see college as an option because it’s too costly or they can’t go for legal reasons. And some teachers believe students need to go to college and others believe not, so there is sometimes a fight about that. But our counselors have been very open to providing the students a range of alternatives, so we don’t have too much of a problem. There is a little prejudice for those who are college-bound versus those who are not, but within the school environment, it’s open for all the options.

Gigi: Do you think most of your students are going to have to leave the community in order to get the jobs they want?

Shirl: The statistics show that the percentage of people who come back to Smithville is on the decline, and I talk to them about that. They must understand that they will have to follow opportunity. It’s interesting when I have those conversations, there are more and more students who share out in the classroom, “I have just moved here. I have not lived here my whole life, like 80% of you. My dad lost his job so he had to transition.” That helps with the conversation. So I tell the students, imagine you’re going to have to face that seven times. Technology will turn over a job or a company will merge. And I’ve added an entire unit on the gig economy and how it’s parallel to entrepreneurship. They have to embrace the concepts of flexibility and variability, based on all the information the Fed continues to provide. One of the best things about the Fed is that sometimes, because it’s so recent, you don’t know that you’re going to need the information.