By Tim Todd

Explore Esther George's career

- Looking back on leadership

- In my office with President Esther George

- Farewell message from the President

The drive from the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City’s headquarters to the rural northwest Missouri farm where Esther George grew up takes about an hour, depending, of course, on how long it takes you to get out of the city traffic.

Faucett, Missouri, is an unincorporated community of around 250 residents just off Interstate 29. It is probably best known as the former home of the Farris Truck Stop—a gas station and restaurant that was popular with interstate travelers and local farmers. It was somewhat renown for an old tractor-trailer turned billboard that towered above the interstate starting in the 1970s and became a regional landmark.

The truck stop, however, was a relative newcomer. George’s ancestors started plowing ground for the Roundtree Farm in the late 1830s. It is the same land where Walter and Barbara Landis raised George and her three siblings and where, in 1981, she would marry classmate Kevin George, and where, later, their children, Landis and Leah, and their children, would play.

But in the 1970s, it was where Esther, like every other farm kid in America, worked for the family enterprise— “I made my 25 cents an hour cutting weeds out of soybeans and doing chores”—while they dreamed about being somewhere else.

Esther George, wearing her father’s work hat and gloves, as a child on the Landis family farm in Faucett, Missouri.

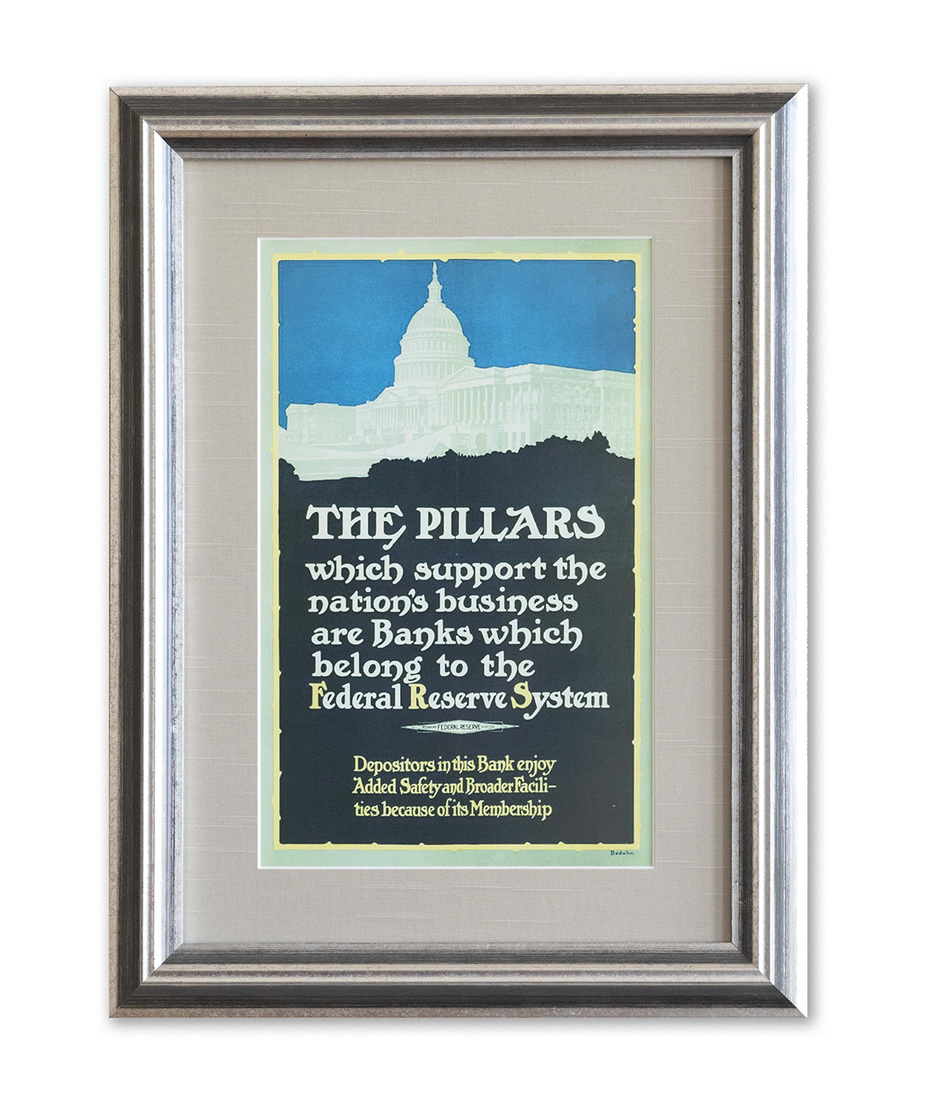

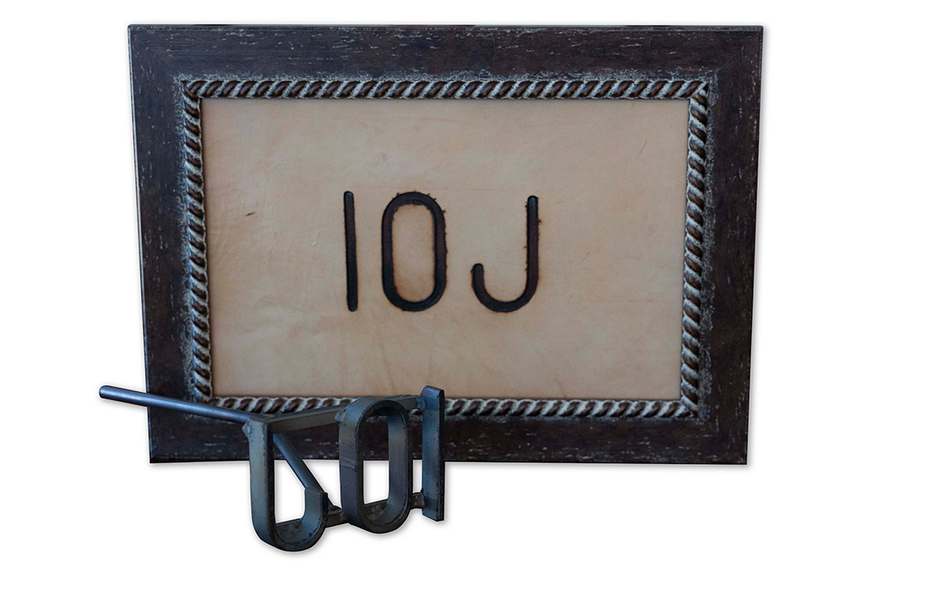

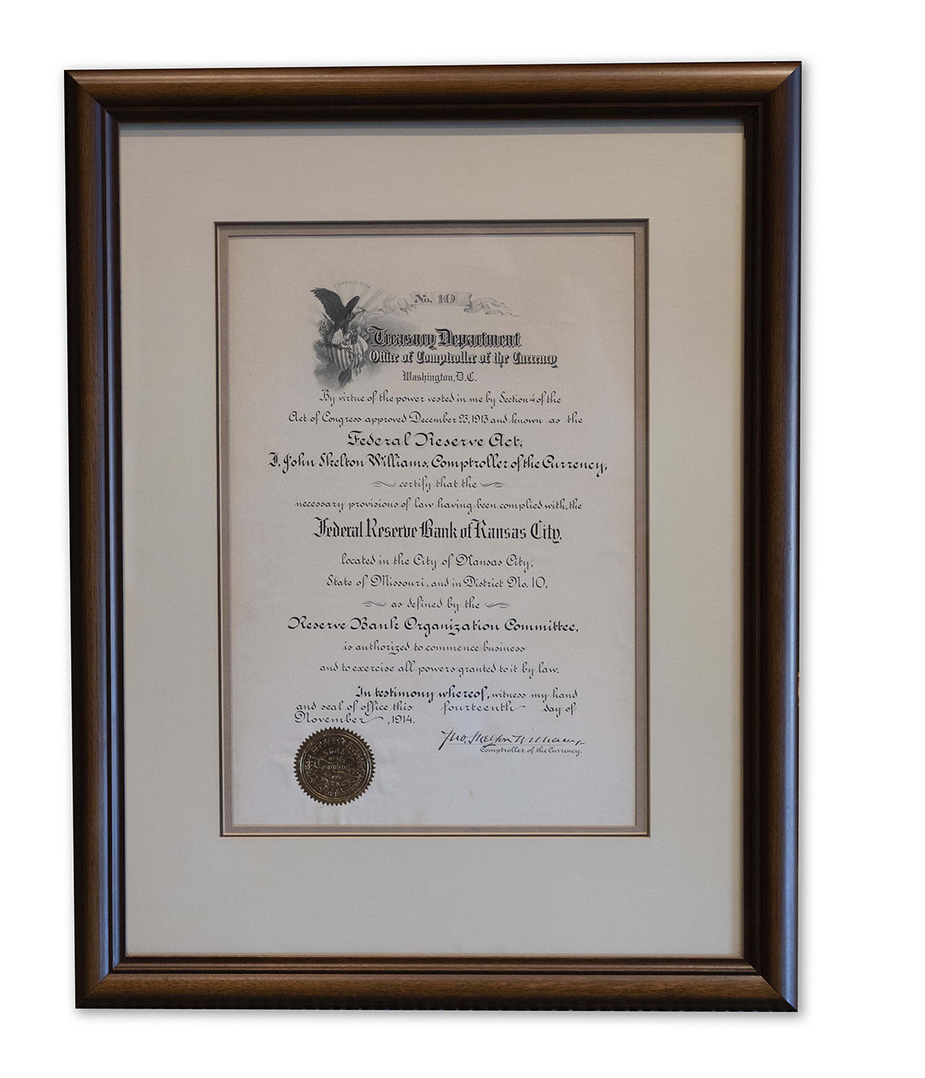

Looking back: Events and milestones during Esther George’s career at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City

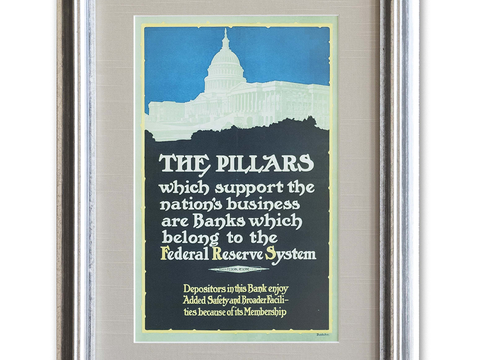

Eventually, that somewhere else would be the President’s Office of the Federal Reserve Bank in downtown Kansas City. In 2011 she became only the ninth president in what was at that time the Bank’s nearly century of service to the Tenth Federal Reserve District.

In early 2023, under requirements for Reserve Bank presidents, George will retire after she reaches age 65. Her journey from the farm to the Fed, however, was not solely along the interstate. First, there was a detour through France. And before that, there was a trip to the local bank to figure out how to pay for it.

Early lessons

When George told her parents that she wanted to take part in a foreign exchange program that was sending U.S. high school students to France, they were supportive. The idea of studying abroad had become increasingly popular after World War II. By the mid-1970s, such programs were comparatively rare, especially for students in rural Missouri.

Still, her parents were supportive, even if the cost was a stretch for the family budget. Growing up, George would sometimes accompany her father on those parts of the family business that happened off the farm, including trips to a bank in nearby St. Joseph. And here she found herself again; this time the conversation was not about the farm, but about France. When the loan officer started asking questions about the loan, including how much money she had available, George looked to her father. His look in response made it clear that it was going to be her loan and her responsibility.

“So, my commitment was that I was paying for it,” she said. “I would go in the bank with my loan coupon and my money and make the payments.”

While she learned those important life lessons that parents like to instill in their children about making plans and earning your own way, she also noticed something else. The bank was a world very different from the farm.

“If you grow up on a farm, summer jobs aren’t fun, and they don’t pay well,” she later told a reporter. “So going to the bank, I thought, ‘This is great! It’s clean. It’s cool in the summer. This would be a good place (to work).’”

The bank must have also been impressed by the teenager who was paying her own way to Europe.

Soon, she was working at the bank, both in high school and while attending college at Missouri Western State University where she majored in business administration.

As a high school student, Esther George traveled to France with the help of a loan that was her first personal interaction with a local bank.

At a time when many payments were made via check, she sorted the thousands of checks that had been processed and were sent monthly back to bank customers in their statements. Sometimes, she worked as a teller or filled-in in other areas when there was a need. It was a first-hand education in banking, but for someone who would spend a lifetime working closely with community banks, the most important lesson may have been the one that came with that first visit. The bank was not solely a place to deposit money or that worked with her family’s business.

“When the bank gave me the loan that allowed me to go to France, I viewed it as the bank was helping me do something that I wanted to do,” she said.

And her time in France showed her a world of possibilities well beyond the farm.

In college, she became interested in international banking—a career that a local reporter in that less enlightened time said was “an atypical career for most young women.” She went back to Europe, this time as a college student – and again thanks to a bank loan—where she toured European banks and exchanges for college credit.

After graduation, she set her sights on New York City. She took a job with Dun & Bradstreet, the firm that compiles and provides financial and commercial data, hoping it would lead her there. Instead, the position was in the Kansas City office and the job was largely about making cold calls to businesses—some who had no interest in talking with her—and trying to get them to share details about their activities. When she saw in a newspaper ad that the Kansas City Fed was looking for bank examiners, she jumped at the chance to change careers.

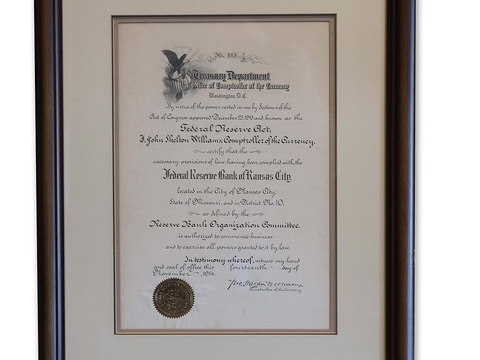

She joined the Bank on April 5, 1982, as an examiner trainee. Exactly three months later, on July 5, 1982, Oklahoma City’s Penn Square Bank failed, marking the first event in what became a banking crisis that was felt deeply across the communities of the Tenth Federal Reserve District and rippled across the U.S. banking system.

The Federal Reserve

In her own words: Esther George

A relatively small Oklahoma bank, Penn Square, was heavily involved in oil and gas lending. Although regulations restricted how much the bank could extend to an individual borrower, Penn Square officials could lend above that amount by selling loan participations to other banks, including some of the largest in the United States. When energy markets inevitably turned lower in the spring and summer of 1982, the loans became increasingly precarious. Soon, Penn Square failed and eventually others were pulled down with it. Meanwhile, the plummeting energy and agriculture markets also created problems for Tenth District banks that had no direct relationship to Penn Square but had been involved in extending credit in both of those areas. It was one of the most difficult economic periods in the region’s history. By the end of the 1980s, 350 banks in the Tenth District failed or received assistance as a result of the crisis.

As someone new to the job, George found herself in a situation in which the typical development and training process for a new hire had become a luxury that would be forgone. It would become on-the-job learning in the midst of a crisis.

“When you are in a time of stress, the learning curve is steep,” she says. “As a trainee, the Fed wanted you to go out to banks that they were pretty confident were well run and in good shape. In 1982 and ’83, I don’t know that there were many of those.”

In 2016, Esther George was photographed in her office by The Kansas City Star.

“It ended up being a time of stress in the economy, but that also was an opportunity to learn.”

For George, this meant she spent a lot more time observing and listening than she did talking. When she saw that her peers were getting better and more detailed answers from bankers during the examination process, she closely watched what they did and how they asked questions.

The head of a large bank in one Tenth District city asked her, seemingly at random during a conversation, how often she had been to the local symphony. She recognized that the question was not about her interest in music, but instead about her understanding of and engagement with the community. To really understand a bank, she realized, you had to understand the community it served.

The listening served her well. She was promoted twice in 1983 and again in 1984. Within a few years, she managed the discount window, where banks can obtain collateralized loans to meet short-term liquidity needs, often overnight. Generally, discount lending rises during times of financial stress and is a key mechanism the central bank uses to ease pressure on the financial system.

She continued her education, earning an MBA from the University of Missouri-Kansas City. She graduated from the American Bankers Association Stonier Graduate School of Banking and the Stanford University Executive Program.

In 1995, she became an officer. She supervised researchers who were brilliant in their understanding of the financial system and in their work.

Esther George spoke at a 2015 event in Kansas City hosted by the Central Exchange, which promotes women´s empowerment and achievement.

“I didn’t have the same research background as them, but I could pay attention to learn what made their job work,” she said. “It’s not so much what you know, but what you can figure out.”

Later she was transferred to the Public Affairs Department, and after that assignment she moved again, to become the head of Human Resources. Soon she was promoted to senior vice president and was made the head of Supervision and Regulation, known today as Supervision and Risk Management. In a bit of an echo of her beginnings as a bank examiner on the eve of a major crisis, she became the Tenth District’s top regulator on Aug. 1, 2001, responsible for the regulation of nearly 200 state member banks and 1,000 bank and financial holding companies.

Six weeks into the new job, the 9/11 attacks occurred, and the Fed moved to an emergency footing to keep the banking system open and operating—keeping money in bank ATMs and commerce flowing at a time of tragedy and turmoil—much of it directed at the heart of the American financial network. She was in the same position in 2007 when the housing bubble burst and the subprime mortgage crisis threatening the availability of credit to families and businesses and forcing the Fed to respond. In 2009, with what had by then become the Great Recession underway, she was sent to the Federal Reserve’s Board of Governors in Washington, D.C., to serve as the interim head of supervision. There, she led the supervision of all banks, including the largest in the United States.

In August of that year she was promoted to first vice president of the Kansas City Fed. In 2011, when Thomas Hoenig retired under the Fed’s mandatory retirement rules for Reserve Bank presidents, the Kansas City Fed’s Board selected George as his successor.

The presidency

In the eyes of the public—particularly those who closely watch financial markets—the most visible part of the job for a Reserve Bank president is participating in the Federal Open Market Committee’s policy deliberations.

The transcript of her first policy meeting shows she was not intimidated. At one point, she challenged some of the ideas about a policy framework proposal then under consideration. Soon, she made headlines after dissenting—disagreeing with the FOMC’s policy decisions—in her first meeting as a voting member and in nine of her next 12 votes.

“I found myself at the FOMC table, where I knew I had a lot to learn about monetary policy theories and frameworks, but by understanding the banking system in the 1980s, all the way through the crisis in 2008-09, I also appreciate it for what is occurring in the real economy,” she said later. “I studied hard, but I thought of it as my job to say what I thought. These are decisions that are affecting millions of people, and I needed to be intellectually honest about that.”

In a 2016 profile of George published in American Banker, Oklahoma State Banking Commissioner Mick Thompson offered to a reporter his perspective of George’s policy votes.

“A lot of times…the economists who report to the (Federal Open Market Committee) have never been in the trenches to see what actually happens in community banks,” he said. “Unfortunately, not everything in the real-world fits within a neat box or computer program. I think Esther understands what sometimes gets lost if you have not actually been in the small community banks.”

The role of policymaker, however, is only part of the Reserve Bank president’s job. George is the Chief Executive Officer of a Reserve Bank that serves a seven-state region: western Missouri, Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma, Wyoming, Colorado and northern New Mexico. As George prepares to retire, the bank has more than 2,200 employees— twice as many as were on the job when George began her presidential tenure in 2011.

Under her leadership, the Bank has taken on expanded System and U.S. Treasury work that has helped more than triple the number of employees involved in technology.

The Kansas City Fed is heavily involved in the payment system—George was a key leader in the development of FedNow, a near real-time payment service scheduled to launch in 2023—and administers programs for the U.S. Treasury. This is in addition, of course, to the Bank’s role in financial supervision and monitoring the pulse of the regional economy.

This was also work that remained critically important as the COVID-19 pandemic thrust the world into a period of uncertainty and very nearly shut down the U.S. economy.

“It was a type of crisis that none of us have ever known before,” George said. “You don’t have a playbook other than to make people’s health and safety a top priority.”

The Bank moved almost overnight into a remote working environment and was able to continue performing at a high level. As her retirement draws near, George says it is yet to be determined what, exactly, the pandemic experience will mean for the nature of the workplace. Similarly undetermined are the long-term ramifications for the economy.

At the time of her appointment, George received a lot of attention as a woman in an arena that was dominated by men. Few women had been Reserve Bank presidents or held senior positions at the Fed Board of Governors. She had become for some a role model.

Under her leadership, the Bank created a Division of Community Engagement and Inclusion, increasing the focus on creating a diverse and inclusive culture both within the Bank and for its employees, but also outside of the Bank focused on community and stakeholder engagement in the communities that the Bank serves.

“It is really important to me,” she said. “The culture of the Bank needs to be one where it should feel like we are all involved in work that is important.”

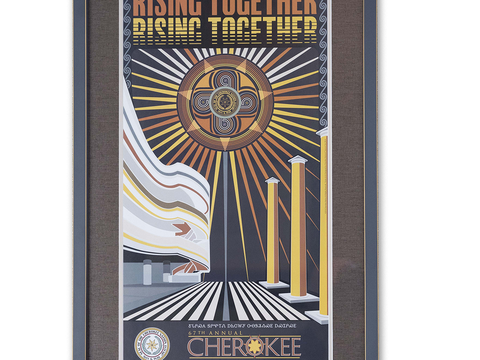

Meanwhile, she has also done much to raise the profile of female economists. Each August, the Kansas City Fed hosts the Jackson Hole Economic Policy Symposium, one of the world’s premier events for central bankers, economists and policymakers.

The economics profession is predominately male. There had been occasional female presenters in Jackson Hole, but program diversity accelerated under George’s tenure.

As the person with the final say on the invitation list and program, she worked diligently to connect with female economists and expand the Bank’s network of connections. While it was never an announced initiative, over the years the press began to notice an increasing number of female economists in Jackson Hole. Soon, they labeled it the “Esther effect.” In 2022, George’s final symposium as Bank president, nearly half of the presenters were female as were many of the participants in attendance.

2022 Jackson Hole Symposium.

“When I think about the path I followed and my career, it did not happen because I had any particularly unique insight,” she said. “It was because somebody had confidence in me and it allowed me to work my way up to positions that I never would have imagined.”

One of those who had confidence was Terry Moore.

“Esther is a very humble person,” said Moore, former head of the Omaha Federation of Labor AFL-CIO in Omaha, Neb.

In 2011, Moore, who was on Kansas City Fed’s Board of Directors, chaired the search committee that chose George to succeed Hoenig. He said during the selection process it soon became apparent that she was the best choice for the job.

“Esther is someone who worked very hard and who often put herself outside of her comfort zone,” Moore said. “When we were looking at candidates for the job, here was someone who had not only a wide range of experiences at the Fed, but also had a real depth of knowledge about the Fed and the financial system and the economy. She was the ideal candidate.

“What she has accomplished as president, and the way she’s been an advocate for our District has really proven what we saw in her and what many others also saw throughout her career.”