Paying bills can be a tedious and costly process, particularly for low-income consumers. Relative to the average consumer, low-income consumers tend to use costlier payment instruments and transaction types to pay their bills, even if they have access to cheaper payment methods. In this briefing, I examine potential explanations for this trend and show that financial exclusion alone cannot fully explain low-income consumers’ reliance on costlier bill payment methods. Even low-income consumers with bank accounts tend to use costlier methods, suggesting other factors—such as cash flow constraints or a lack of trust in electronic payment products—may play a role.

The Costs of Paying Bills

Many types of bill payments incur costs for consumers, and these costs vary widely depending on the payment instrument (cash, money order, checks, cards, or bank account number) and transaction type (in person, by mail, over the phone, online, or automatic bill payment)._ Some payment instruments can be costly to obtain, such as money orders and checks, while others can be costly to use, such as some credit cards. Consumers usually incur the highest costs when paying a bill in person (regardless of payment instrument) due to transportation costs and the lowest costs when paying over the phone or online; paying through the mail, which incurs postage costs, is somewhere in between._

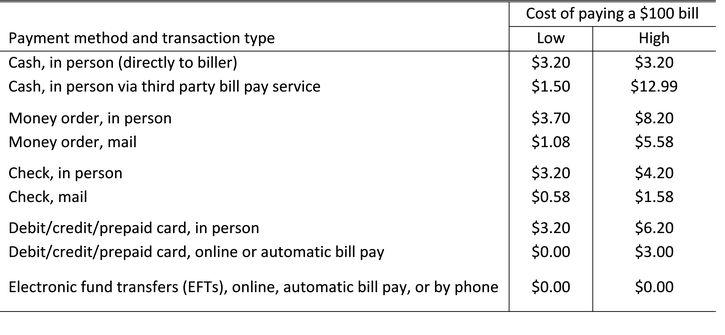

Table 1 shows the low and high ends of the estimated costs for consumers to pay a $100 bill with commonly used payment methods and transaction types._ The costs range from $0 to $12.99. Overall, paying bills using paper methods such as cash, money orders, and checks tend to be costlier than paying with electronic methods such as cards and electronic fund transfers (EFTs), in large part because consumers cannot use paper instruments to make payments online (the least costly transaction type).

Table 1: Estimated Costs of Bill Payments for Common Payment Methods

Sources: Bureau of Transportation Statistics, U.S. Postal Service, and author’s calculations.

The costliest payment method presented in Table 1 is cash, especially when consumers make cash payments via third-party providers of bill pay services. When paying a bill with cash in person, consumers are likely to incur transportation costs. According to the Bureau of Transportation Statistics, the average passenger transit fare was $1.60 in 2019, implying consumers may incur round-trip transportation costs of $3.20 on average each time they pay a bill in person. Although most billers do not charge consumers fees for paying in cash, third-party bill pay providers such as MoneyGram and PayNearMe do. The cost of paying a bill with cash varies widely when consumers use a third-party bill pay service, ranging from $1.50 to $12.99, depending on the biller and the speed of delivery. Generally, fees are higher for faster payment delivery speed. Because these services are available at retail locations, such as grocery, drug, and convenience stores, I assume consumers may pay bills when they shop there and thus do not incur extra transportation costs.

The cost of paying a bill using a money order also tends to be relatively high—up to $8.20 per bill—though it varies widely. Providers of money orders charge consumers fees ranging from $0.50 (for postal military money orders) to $5 (for bank money orders). Consumers can pay with a money order either in person at the biller or via mail. Like cash, paying a bill in person could cost consumers an additional $3.20 for transportation. In contrast, paying a bill via mail is considerably cheaper: a standard first-class stamp is $0.58.

The cost of paying a bill with a check is typically lower than with cash and money order. Banks may charge their customers a fee as high as $1 per check, depending on the bank and the type of checking account._ Like money orders, consumers can pay with a check either at the biller in person or via mail, incurring an additional cost according to the transaction type.

The cost of paying a bill using a payment card is generally lower than using paper methods, though it varies by card and transaction type. Banks and credit card issuers generally do not charge their debit or credit card users a transaction fee, but some prepaid card providers charge users a transaction fee as high as $1. In addition, billers may impose a surcharge of around 2 to 3 percent of the transaction value on consumers who pay with cards, especially credit cards, to help cover the merchant fees charged by card networks and issuers (which are higher for credit than debit or prepaid card payments). The cost of paying a bill using a payment card can also vary by transaction type: although paying a bill online or by phone does not typically incur extra costs, paying in person or via mail does.

Finally, consumers typically incur no costs for using EFTs to pay bills, making them the cheapest bill payment method. Banks and billers generally do not charge fees to consumers when they pay a bill via a transfer from their bank account or through a direct deduction from their payroll. Moreover, EFTs are typically made online or via automatic withdrawal—and, in rarer instances, over the phone—incurring no additional costs for consumers.

Low-Income Consumers’ Choice of Bill Payment Methods

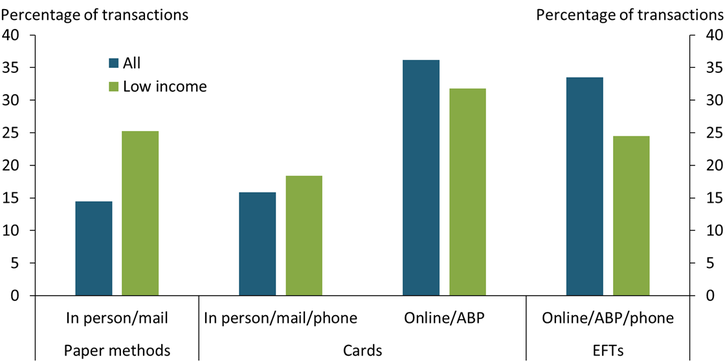

Consumers with different characteristics may also prefer different bill payment methods. Prior research has found that low-income consumers (those with annual household income under $35,000) choose different bill payment instruments than other consumers (Greene and Stavins 2020). To gain insight into how low-income consumers pay their bills, I analyze data from the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta’s 2019 Survey of Consumer Payment Choice (SCPC), which provides details on the payment method and transaction type consumers used for bill payments in 2019._ The green bars in Chart 1 show that in 2019, low-income consumers paid a majority of their bills online using cards, automatic bill pay, or EFTs, which are less costly payment methods.

Chart 1: Average Share of Bills Paid Using Different Payment Methods, All versus Low-Income Consumers, 2019

Notes: ABP refers to automatic bill pay. Paper methods include cash, money orders, and checks.

Sources: Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta and author’s calculations.

However, low-income consumers were less likely than consumers overall (blue bars) to use these cheaper methods. Low-income consumers were particularly less likely to use EFTs (9 percentage points below the average of all consumers) and were more likely to use paper methods (about 11 percentage points above the average of all consumers). Moreover, low-income consumers were significantly more likely to use cash—arguably the costliest paper method—than consumers overall (17.5 percent versus 7.9 percent). Finally, low-income consumers were more likely to pay bills (regardless of method) in person and via mail, thereby incurring higher costs.

Financial Exclusion as a Barrier to Cheaper Bill Payments

Low-income consumers’ above-average tendencies to use paper methods and make in-person or mail transactions for bill payments suggest that they may face barriers to adopting cheaper payment methods. One potential explanation for these tendencies is that low-income consumers are more likely to be financially excluded—that is, unbanked. According to the 2019 SCPC, low-income consumers were over 3.5 times more likely to be unbanked than consumers overall (23.7 percent versus 6.6 percent). Being unbanked limits low-income consumers’ access to cheaper payment methods such as EFTs and debit cards. Although unbanked consumers can use prepaid cards, which are essentially debit cards, many may not own them, as the barriers to bank account ownership these consumers face are also likely to hinder their adoption of prepaid cards (Toh 2021). Moreover, those who do own prepaid cards may have to load funds onto their cards before they can use them, incurring reload fees as high as $5.95 per reload._

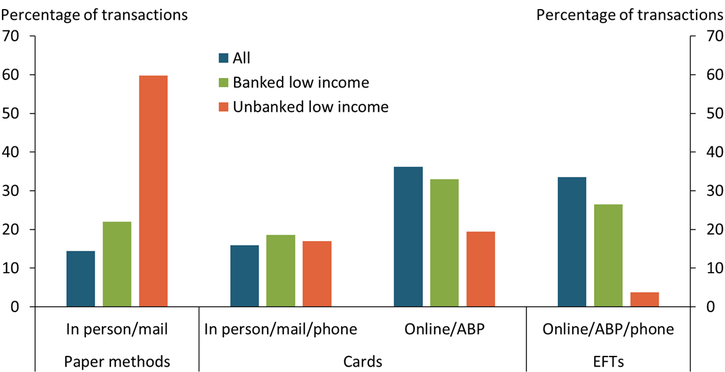

The orange bars in Chart 2 show that unbanked low-income consumers indeed made relatively small percentages of bill payments using cheaper methods such as online or ABP card payments (19.4 percent) and EFTs (3.8 percent). Instead, unbanked low-income consumers paid most of their bills (59.8 percent) via paper methods in person or through the mail (50.9 percent used cash and 8.9 percent used money orders); 15.5 percent used prepaid cards (in person, online, or over the phone)._

Chart 2: Average Share of Bills Paid Using Different Payment Methods, Banked versus Unbanked Low-Income Consumers, 2019

Notes: ABP refers to automatic bill pay. Paper methods include cash, money orders, and checks.

Sources: Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta and author’s calculations.

However, financial exclusion only partly accounts for low-income consumers’ reliance on costlier payment methods. Chart 2 shows that although banked low-income consumers (green bars) paid a larger share of their bills using less costly methods than unbanked low-income consumers (orange bars), they were still more likely to use costlier payment methods than consumers overall (blue bars). In particular, banked low-income consumers were 7.5 percentage points more likely than the overall population to use paper methods to pay bills, and were marginally more likely to use cards to pay bills in person, via mail, or over the phone.

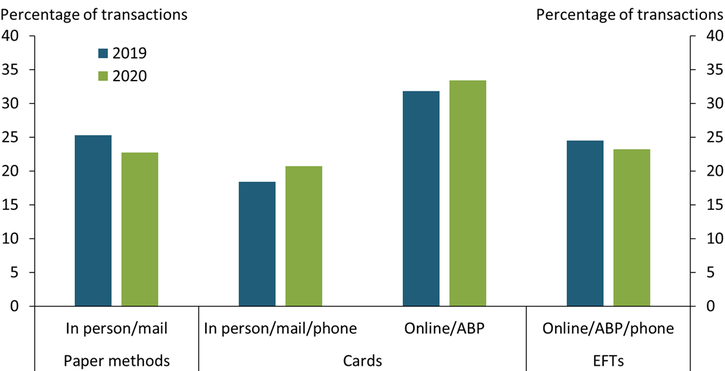

Financial exclusion also cannot fully explain the persistence of low-income consumers’ bill payment choices. Chart 3 shows that even during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 (green bars), when paying bills in person or via mail carried additional health risks, low-income consumers largely used the same bill payment methods and transaction types as they did in 2019 (blue bars). The share of bills paid in person, via mail, or over the phone with either paper methods or cards was roughly the same in 2020 as in 2019 (43.4 percent and 43.7 percent, respectively). Notably, in-person cash payments declined only slightly and remained one of the most common bill payment methods among low-income consumers in 2020, notwithstanding the high perceived health risks of using cash.

Chart 3: Average Share of Bills Low-Income Consumers Paid Using Different Payment Methods, 2020 versus 2019

Notes: ABP refers to automatic bill pay. Paper methods include cash, money orders, and checks.

Sources: Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta and author’s calculations.

Other Barriers to Cheaper Bill Payments

Low-income consumers’ tendency to use costlier payment methods and transaction types regardless of banking status—along with the persistence of these payment choices—suggests that they may face other barriers to adopting less costly methods. One likely barrier is digital exclusion. According to the 2019 Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation Survey of Household Use of Banking and Financial Services, 21.7 percent of low-income households lacked both smartphone and home internet access compared with 9.1 percent of all households, implying low-income consumers are less able to make bill payments online.

A second likely barrier is a lack of trust in or familiarity with electronic payment methods such as cards, bank transfers, and online or automatic transactions. Some low-income consumers, particularly older consumers, may have always paid their bills using paper methods in person or via mail and may not want to or know how to pay their bills a different way. Others may feel less comfortable sharing their payment or bank account information with billers or perceive electronic payment methods and online transactions to be less secure.

A third possible barrier is cash flow constraints. Low-income consumers may be more likely to face cash flow constraints and therefore delay their bill payments until the last minute. Some billers require consumers to submit online payments (via card or bank transfer) one or more business days in advance for the payments to be considered on time, as payments may take several days to post. Consequently, low-income consumers with cash flow constraints may resort to paying their bills in person or using costly third-party bill payment services that offer immediate or same-day delivery.

Addressing Barriers to Cheaper Bill Payments

The cost of bill payments likely imposes a financial burden on many low-income consumers, and boosting bank account ownership alone is unlikely to sufficiently address this problem. Low-income consumers may face multiple barriers to adopting less costly payment methods, from digital exclusion to cash flow constraints. Policymakers seeking to alleviate the financial burden of bill payments on low-income consumers may need to take a multipronged approach, with initiatives to increase digital inclusion (such as expanding and improving the nation’s broadband infrastructure), broaden financial and digital literacy, and promote the use of electronic methods for paying out income and government benefits.

Faster payments services may also help low-income consumers by improving their cash flow, thereby eliminating the need to use expensive expedited bill pay services or in-person payments. Although faster payments services are already available through the Zelle network, they are only accessible to low-income consumers who bank with participating institutions and have the technologies to use mobile or internet banking. Moreover, billers do not currently accept payments via Zelle. The Federal Reserve’s forthcoming FedNow service may play an important role in ensuring that low-income consumers, particularly those who are financially or digitally excluded, have access to faster payments services and can pay bills more affordably.

Endnotes

-

1

An automatic bill payment is a prescheduled, recurring payment that can be set up through a credit, debit, or prepaid card or with a bank account.

-

2

In my analysis, I consider both phone and online payments to be costless; I expect consumers who use these methods to have a phone line or internet connection already, so paying a bill this way would not incur an additional cost.

-

3

The cost estimates presented in Table 1 include only the monetary costs of using each payment method but not the nonmonetary costs (such as the opportunity cost of time), as nonmonetary costs tend to vary widely by individual and are difficult to capture and quantify. The high and low estimates of costs do not provide absolute bounds for the costs consumers would incur; rather, they offer the likely costs for consumers.

-

4

Different banks charge different fees per check written by their customers, and some banks may offer new customers a limited number of free starter checks. Across banks, some premium or preferred checking accounts (typically with higher minimum balance requirements) offer consumers free or discounted checks, whereas basic checking accounts do not tend to offer free checks.

-

5

Although data from the 2020 SCPC are available, I do not use it for the main analysis for two reasons. First, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, 2020 may not be a representative year for consumers’ bill payment choices. Second, the sample size of the 2020 survey is substantially smaller than that of 2019.

-

6

Many unbanked consumers receive funds such as income and government benefits via paper methods and must first deposit these funds onto their prepaid cards before they can use them.

-

7

Greene and Stavins (2020) find that unbanked consumers’ higher tendency to use cash and lower tendency to use online payments to pay their bills holds true even when controlling for other consumer attributes.

References

Greene, Claire, and Joanna Stavins. 2020. “External LinkConsumer Payment Choice for Bill Payments.” Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, Research Department Working Paper no. 20-9.

Toh, Ying Lei. 2021. “External LinkPrepaid Cards: An Inadequate Solution for Digital Payments Inclusion.” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Economic Review, vol. 106, no. 4.

Ying Lei Toh is an economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City or the Federal Reserve System.