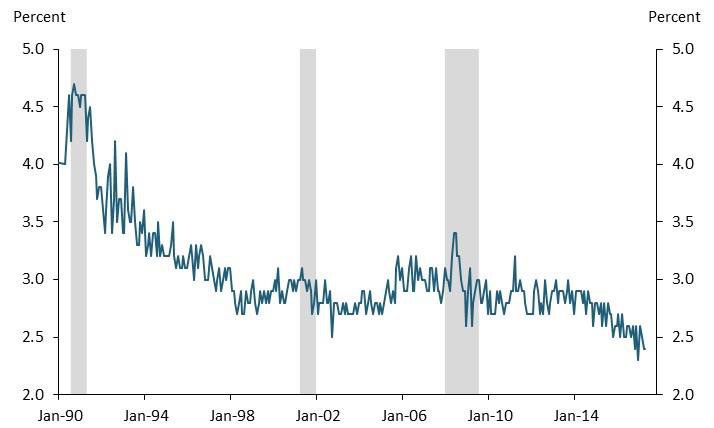

Household expectations for longer-term inflation, as measured by the University of Michigan Survey, have declined over the last few years. Chart 1 shows the median household expectation for inflation over the next five to 10 years._ The decline in household expectations originally coincided with a large drop in oil prices in 2014. However, oil prices have since stabilized, while inflation expectations have remained near historical lows. As a result, some policymakers have flagged deteriorating inflation expectations as a risk to the inflation outlook over the next few years._

Chart 1: Median longer-term inflation expectations

Note: Gray bar denotes National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER)-defined recession.

Sources: University of Michigan and NBER (Haver Analytics).

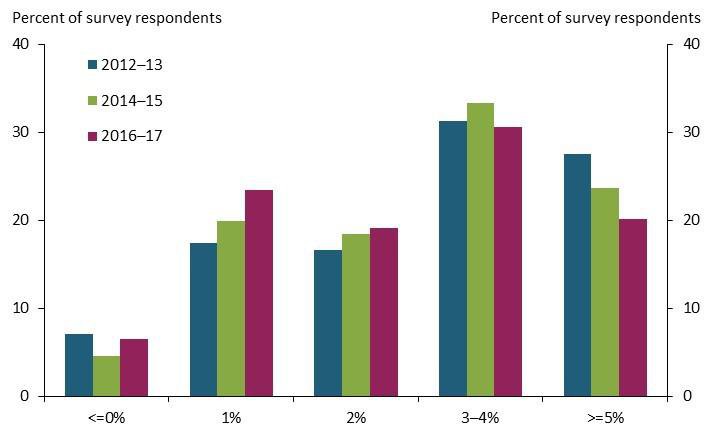

To understand the risk that lower household inflation expectations pose to the inflation outlook, it is helpful to understand why consumer inflation expectations have declined. Using the micro-level data used to construct the Survey median in Chart 1, we can examine individual household forecasts for longer-term inflation over time. The bars in Chart 2 show the percent of household respondents who projected certain longer-term inflation outcomes over a given two-year period.

Chart 2: Household longer-term inflation expectations over time

Sources: University of Michigan and authors’ calculations.

Over the last several years, the number of households with high inflation expectations has fallen, while the number of households with low inflation expectations has increased. In 2012–13, almost 30 percent of households surveyed expected inflation over the next five to 10 years to be at or above 5 percent. However, that number fell to roughly 20 percent in 2016–17. In addition, the number of households with lower inflation expectations rose by roughly the same amount as the drop in households with higher inflation forecasts. Almost one-quarter of households surveyed over the last two years expect longer-term inflation of about 1 percent.

Given the FOMC’s longer-run 2 percent inflation objective, monetary policy makers may find this decline in inflation expectations troubling. Over the last five years, core PCE inflation has remained consistently below 2 percent. If this recent weakness in realized inflation has led some households to mark down their inflation expectations, it could signal lost confidence in the FOMC’s ability to meet its price stability mandate.

To explore this possibility, we match respondents’ expectations about longer-term inflation with their views about how policymakers have handled the economy. Specifically, we use responses to the question, “as to the economic policy of the government—meaning steps taken to fight inflation and unemployment—would you say the government is doing a good job, only fair, or a poor job?” to ascertain how households perceive recent inflation outcomes. If households with low inflation expectations perceive recent inflation outcomes as inconsistent with the Committee’s longer-run inflation objective, then we assume that these households would give policymakers low marks on their handling of the economy. Conversely, if households believe the recent inflation dynamics are consistent with the Committee’s objective, then we assume they would give policymakers high marks.

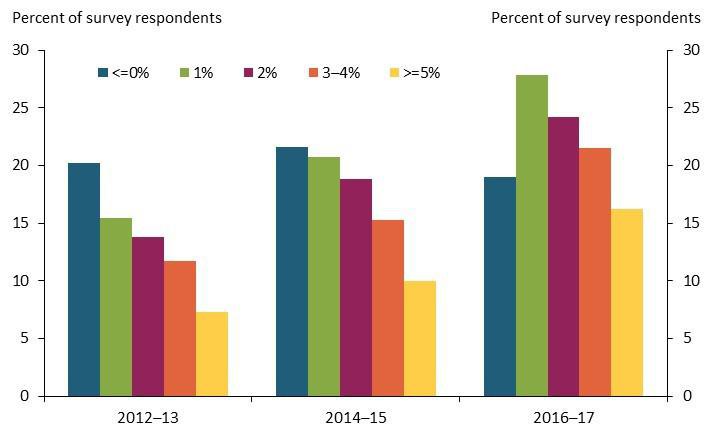

We find that households with lower inflation expectations tend to think the government is doing a better job managing unemployment and inflation than households with high inflation expectations. Chart 3 shows the percent of households that believe the government is doing a “good job” handling inflation and unemployment both across time and sorted by their longer-term inflation expectations.

Chart 3: Household respondents reporting "good" government policy by longer-term inflation expectation

Sources: University of Michigan and authors’ calculations.

The number of households that believe the government is doing a “good job” has risen over the last several years, likely due to improvements in the labor market. Moreover, households with inflation expectations of 1 percent are more likely to approve of policymakers’ handling of the economy than those with inflation expectations significantly above 2 percent. Thus, policymakers may be less concerned with the recent decline in the median household expectation for longer-run inflation, since households with low inflation expectations have not expressed greater dissatisfaction with their handling of the economy.

Endnotes

Reference

Brainard, Lael. 2016. “External LinkThe Economic Outlook and Implications for Monetary Policy,” (speech delivered at the Council on Foreign Relations, Washington, D.C., June 3).

Brent Bundick is an economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City. Trenton Herriford and Emily Pollard are research associates at the bank, and A. Lee Smith is an economist at the bank. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City or the Federal Reserve System.