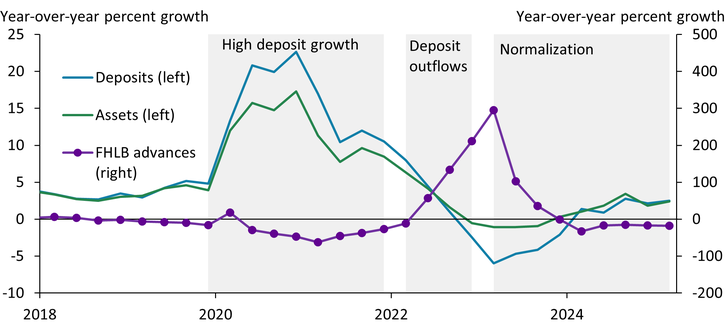

The composition of bank funding has evolved substantially since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The shaded regions in Chart 1 show how bank balance sheets have evolved in three distinct phases since the pandemic. During the early stages of the pandemic, banks experienced unprecedented growth in deposits (blue line), attributed initially to withdrawals on banks’ credit lines and subsequently to increased fiscal stimulus, higher savings rates, and Federal Reserve asset purchases (Castro, Cavallo, and Zarutskie 2022). As the Federal Reserve tightened policy, banks lost deposits and used Federal Home Loan Bank (FHLB) advances to replace deposit outflows (dotted purple line)._ Then, after a period of bank failures and stresses in March 2023, the composition of bank funding began to normalize, with market sources replacing nonmarket funding._

Chart 1: Growth in bank assets and liabilities since the pandemic

Source: Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (Haver Analytics).

The swings in deposit funding have renewed attention on banks’ use of funding from FHLBs. FHLBs were created in 1932 as government-sponsored enterprises with the primary goal of supporting housing finance by extending low-cost financing to savings and loans institutions (Federal Reserve History 2024). However, they have since evolved into a funding source for banks of all sizes involved in housing finance.

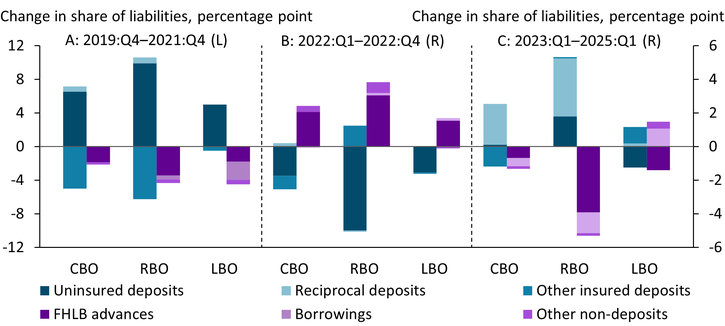

Chart 2 shows that the three phases of bank funding since the onset of the pandemic was broadly consistent across banks of different size classes, particularly with respect to their use of FHLB advances. In the first phase (Panel A), the large influx of uninsured deposits (dark blue bars) due to extraordinary pandemic measures reduced banks’ need for other forms of borrowing, principally FHLB advances.

Chart 2: Changes in the composition of bank liabilities by bank size

Notes: Bars reflect changes in shares of total liabilities and sum to zero. Deposit and non-deposit liabilities are in shades of blue and purple, respectively. “Other insured” and “Other non-deposits” categories reflect the residuals of total deposit and total non-deposit liabilities, respectively.

Sources: Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council and authors’ calculations.

In the second phase, this trend reversed. Following monetary policy tightening in 2022, the inflow of deposits first slowed and subsequently reversed as alternative financial instruments offered higher yields. Panel B of Chart 2 shows sharp deposit outflows (dark blue bars) were replaced by more rate-sensitive borrowing, mostly in the form of FHLB advances (dark purple bars). While most banks turned to FHLB advances to replace deposit outflows throughout 2022, funding stress peaked with bank failures in March 2023._ At large banks, deposits declined least (as a share of liabilities) but were still replaced almost entirely with FHLB advances rather than funding from capital markets.

As liquidity pressures eased, banks replaced FHLB advances with funding from other sources during the third phase of balance sheet evolution. Panel C of Chart 2 shows that with limited access to capital markets, regional and community banks accelerated their use of reciprocal deposits (light blue bars) to replace FHLB funding._ Even after stresses have dissipated, capital market access for small banks seems limited. In contrast, large banks borrowed from capital markets (light purple bars) to replenish funds. Such differences in financing highlight structural differences in capital market access determined by bank size.

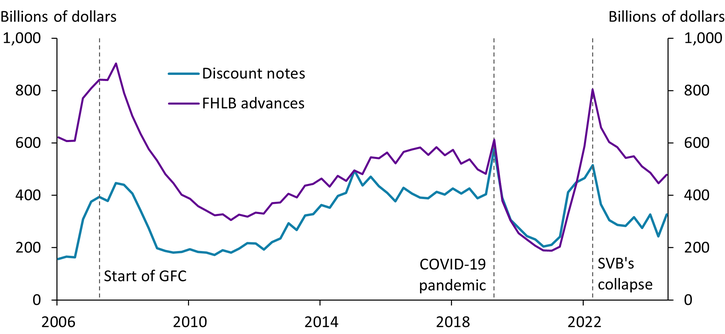

These differences also raise the question of whether capital markets, instead of the FHLB, can be a funding source for large banks in the face of deposit outflows. FHLB advances remain the primary source of contingent funding because they are cheaper than other forms of borrowing._ Chart 3 shows that FHLBs’ role as a contingent source of funding has strengthened since the global financial crisis (GFC). In particular, FHLBs have actively increased borrowing through the issuance of short-term discount notes (blue line) during periods of stress largely with a view to meet the higher bank demand for contingent funding—in essence, acting as a provider of liquidity in periods of stress._ Further, large bank dependence on FHLB funding has also been reinforced by post-crisis regulations: Money market reforms in 2014 led to a reallocation from prime funds, which directly financed short-term commercial paper and certificates of deposits issued by large banks, to government funds, which financed FHLB discount notes (Anadu and Baklanova 2017). Moreover, post-crisis liquidity regulations directed mostly at large banks afford a favorable treatment to FHLB borrowing (Gissler, Narajabad, and Tarullo 2022). Taken together, these factors have increased large bank exposure to FHLB borrowing since the GFC—even though market financing remained readily available.

Chart 3: FHLB outstanding discount notes and advances to depository institutions

Notes: Discount notes are short-term debt issued by FHLBs. FHLB advances are secured loans to depository institutions.

Sources: Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation and Federal Home Loan Banks Office of Finance (both accessed via Haver Analytics).

Given its increasing relevance to banks, the FHLB system has faced more attention, especially on its role as provider of liquidity in periods of stress. For example, Cecchetti, Schoenholtz, and White (2023) argue that as FHLB advances become an integral part of banks’ asset-liability management, they can help troubled banks escape market discipline and supervisory scrutiny. Moreover, because FHLB advances are overcollateralized and have seniority over all other debt, they ultimately increase the costs of resolving failing institutions. Finally, the FHLB liquidity backstop not only reduces liquidity demand at the Federal Reserve’s discount window but could also increase the associated stigma for banks._

Reducing incentives for FHLB borrowing in liquidity regulation and encouraging those banks that can borrow directly at capital markets to do so could bring much needed market discipline. This could also help bring more funding to smaller community-based organizations that have limited access to capital markets.

Endnotes

-

1

To better delineate bank balance sheet evolution, a gap of one quarter between each of the phases is shown in Chart 1. Although deposit outflows are shown up to 2022:Q4, they peaked around the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank in mid-March 2023.

-

2

Bank nonmarket funding includes not just FHLB advances but also borrowing from the Federal Reserve’s discount window, the Standing Repo Facility, and emergency liquidity programs such as the Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP).

-

3

Almost all banks that experienced a run on deposits borrowed from FHLBs, but the median bank from this group did not borrow from the Federal Reserve’s discount window (Cipriani, Eisenbach, and Kovner 2024).

-

4

Reciprocal deposits allow deposits to be insured after the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation’s (FDIC) $250,000 limit by exchanging excess deposits with another bank, creating a new account that is fully insured. Community banks are defined as institutions with less than $10 billion in assets, regional banks are institutions with between $10 billion to $100 billion in assets, and large banks are institutions with over $100 billion in assets.

-

5

As government-sponsored enterprises, FHLBs benefit from an implicit federal guarantee, which helps them obtain cheaper capital market funding for their advances. Moreover, FHLB advances have super senior liens to all other bank debt. Finally, banks hold FHLB equity and adjusted for payouts, borrowing from the FHLB is even less expensive.

-

6

As a provider of liquidity in periods of stress, the FHLB backstop lowered demand and arguably raised the stigma of borrowing from the Federal Reserve (Ashcraft, Bech, and Frame 2010).

-

7

Banks are also reluctant to borrow from the discount window because of the stigma associated with discount-window credit (Ashcraft and coauthors, 2010). In a recent report, the Federal Housing Finance Agency (2024) acknowledges that the FHLB system is “not designed or equipped to take on the function of the lender of last resort.” In the report, the FHFA announced plans to limit large issuances to mitigate “the negative effects that a single large borrower could have on the activity of all members.”

References

Anadu, Kenechukwu, and Viktoria Baklanova. 2017. “External LinkThe Intersection of U.S. Money Market Mutual Fund Reforms, Bank External LinkLiquidity Requirements, and the Federal Home Loan Bank System.” Office of Financial Research, working paper no. 17-05, October 31.

Ashcraft, Adam, Morten L. Bech, and W. Scott Frame. 2010. “External LinkThe Federal Home Loan Bank System: The Lender External Linkof Next-to-Last Resort?” Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, vol. 42, no. 4, pp. 551–558.

Castro, Andrew, Michele Cavallo, and Rebecca Zarutskie. 2022. “External LinkUnderstanding Bank Deposit Growth during the COVID-19 Pandemic.” Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, FEDS Notes, June 3.

Cecchetti, Stephen G., Kermit L. Schoenholtz, and Lawrence J. White. 2023. “External LinkReforming the Federal Home Loan Bank System.” Money and Banking, August 2.

Cipriani, Marco, Thomas M. Eisenbach, and Anna Kovner. 2024. “External LinkTracing Bank Runs in Real Time.” Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Staff Reports, no. 1104, May.

Federal Housing Finance Agency. 2023. “External LinkFHLBank System at 100: Focusing on the Future.” November.

Federal Reserve History. 2024. “External LinkFederal Home Loan Bank Advances.” October 15.

Gissler, Stefan, Borghan Narajabad, and Daniel K. Tarullo. 2022. “External LinkFederal Home Loan Banks and Financial Stability.” Harvard Public Law Working Paper, no. 22-20, June 13.

Joshua Jacobs is a research associate at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City. Rajdeep Sengupta is a senior economist at the bank. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City or the Federal Reserve System.