Conditions have deteriorated in Nebraska’s agricultural economy, where the sector exerts a relatively large influence on the overall economy. Moreover, the outlook for agriculture appears pessimistic relative to both Nebraska’s historical data and conditions in bordering states. Due to the state’s large footprint in agriculture, when commodity prices started to fall in mid-2013, Nebraska was the first state to show signs of weakness in agricultural credit conditions. More recently, the downturn in agriculture likely has contributed to unbalanced economic growth in Nebraska, including weaker activity among Main Street businesses and disproportionately slower job growth in rural areas.

Agricultural Credit Conditions in Nebraska

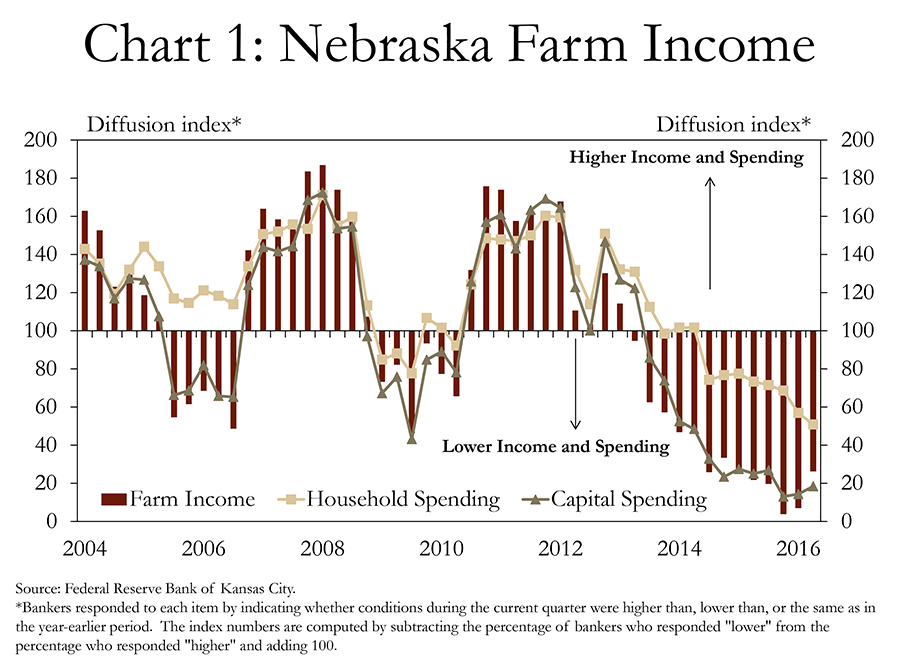

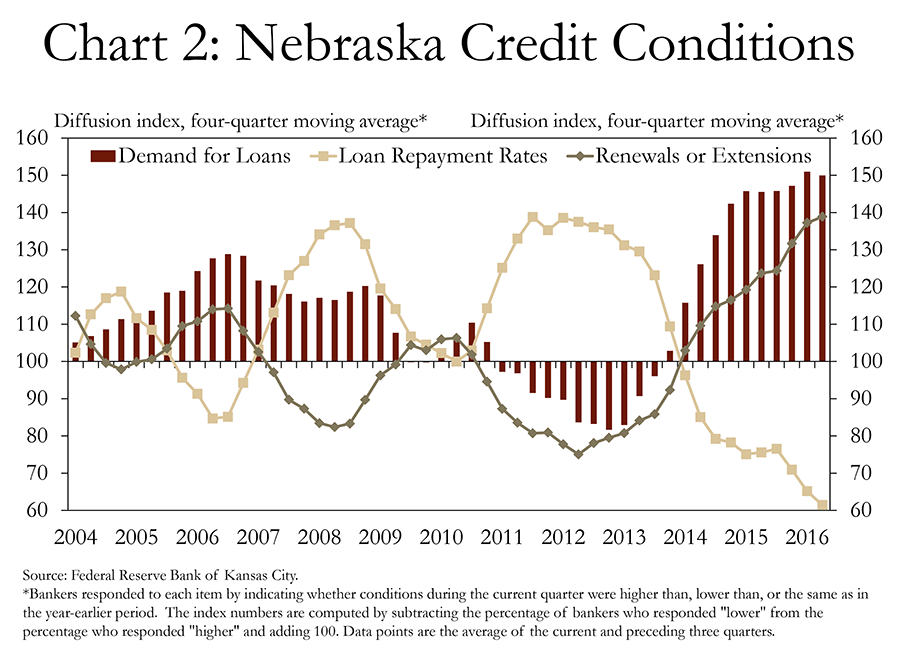

Consecutive quarters of lower farm income have led to weaker credit conditions in Nebraska. Similar to conditions reported for the Tenth District, farm income in Nebraska has declined since mid-2013 (Chart 1). During that time, the decline in household spending and capital spending also has accelerated. Although spending has fallen, demand for farm loans has grown, highlighting the need for financing to cover operating expenses (Chart 2). Lower farm income, combined with increasing demand for operating loans, has weakened some borrowers’ ability to repay loans. In fact, Nebraska bankers have reported lower repayment rates for 10 consecutive quarters.

How do Conditions in Nebraska Compare with Bordering States?

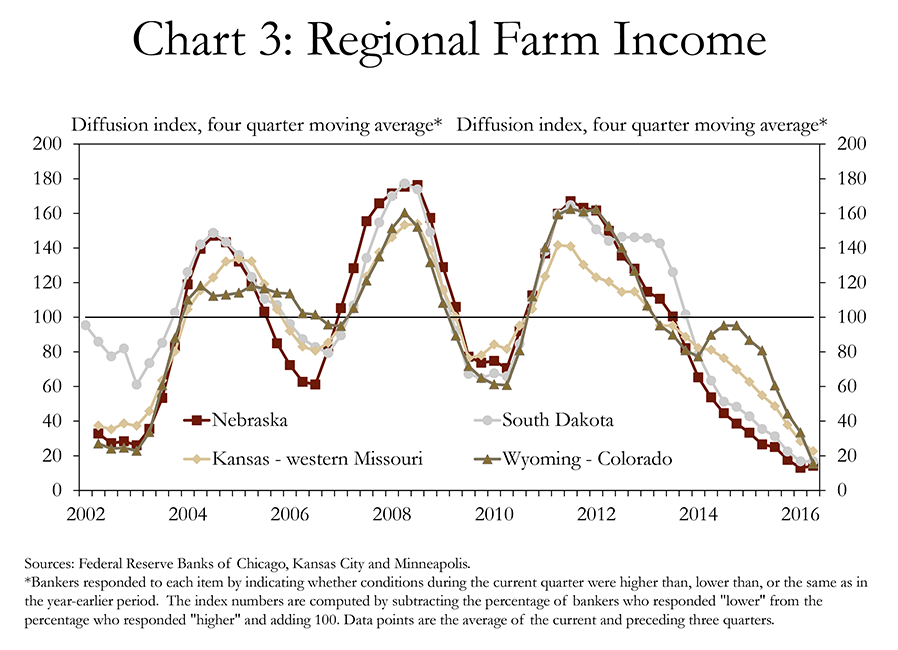

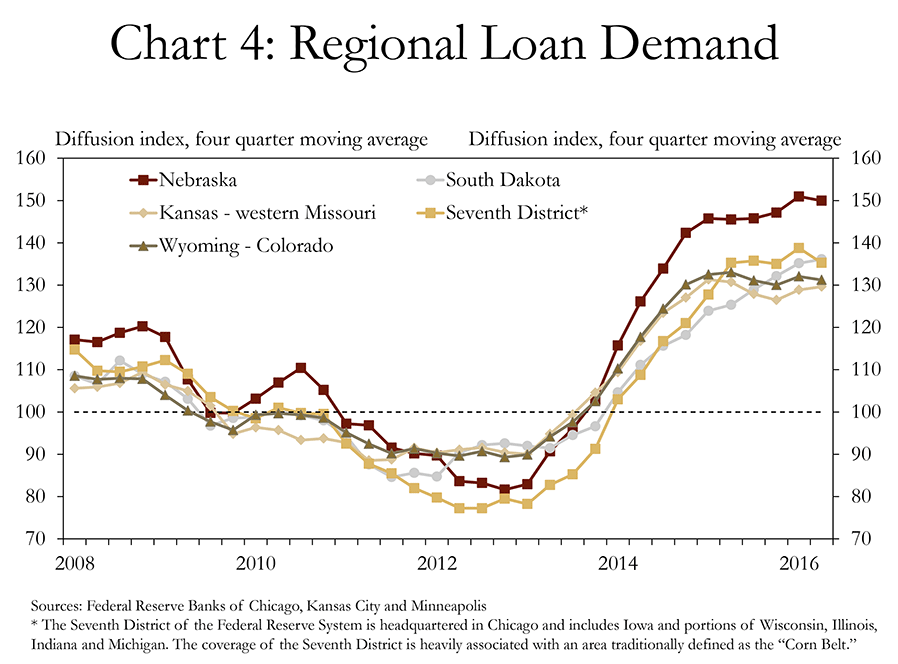

Compared to most bordering states, farm income has declined at a quicker pace in Nebraska. For example, since 2014 a larger percentage of bankers in Nebraska consistently reported sharper declines in farm income than in bordering states (Chart 3). The more rapid pace of weakening farm income in Nebraska has led to a significant rise in demand for non-real estate farm loans. In fact, since 2014 demand for farm loans in all bordering states also has risen. However, the rate of increase in Nebraska also has been consistently higher (Chart 4). A more rapid rate of decline in farm income and steeper rise in demand for farm loans could indicate the environment for farm income recently has been slightly more downbeat in Nebraska than bordering states.

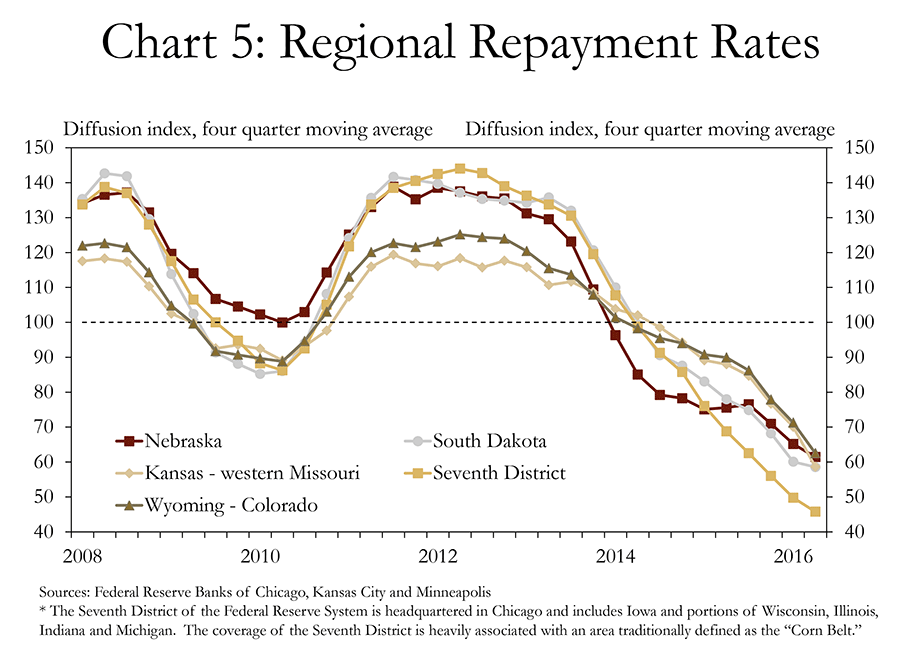

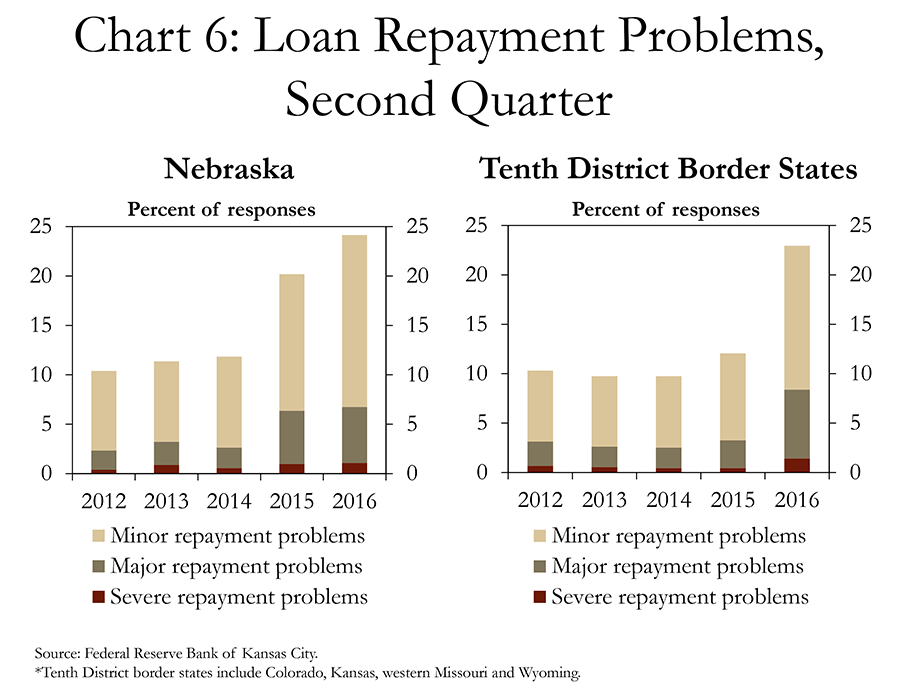

Some indicators of financial stress in the farming sector also have been more pronounced in Nebraska, and appeared earlier, than in bordering Tenth District states. Specifically, for most of 2014 and the first half of 2015, repayment rates for farm loans in Nebraska declined quicker (Chart 5). Nebraska bankers also were quicker to indicate an onset of more severe problems with loan repayments (Chart 6). Likewise, the share of borrowers in Nebraska with increased carryover debt climbed quicker. In each situation, financial strain first was recognized in Nebraska and then more broadly among bordering states.

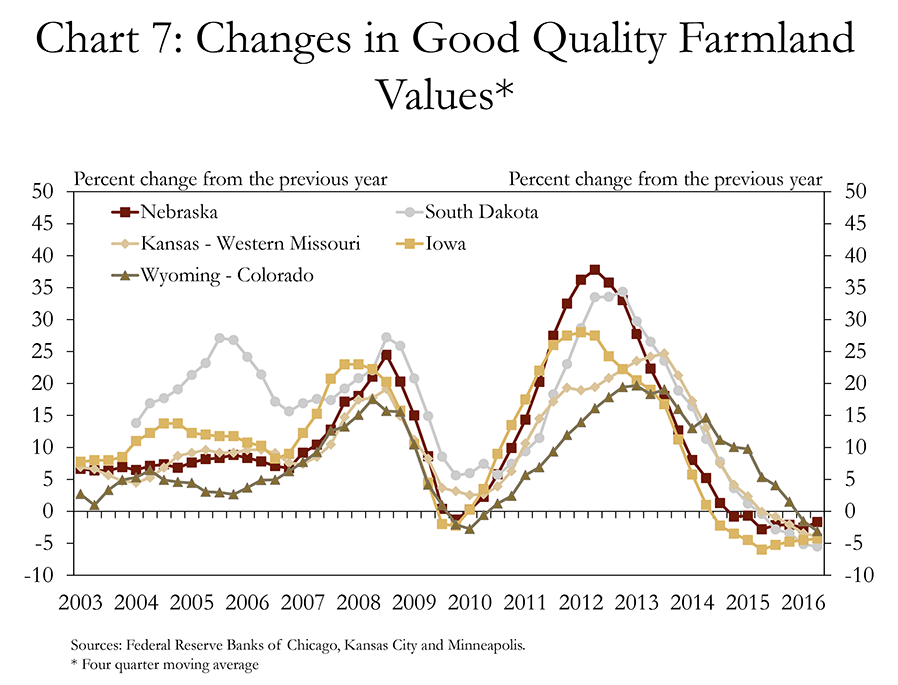

Similar to general measures of farm financial stress, farmland values softened earlier in Nebraska than in most bordering states. Specifically, coming off a peak in early 2012, gains in the value of Nebraska farmland slowed more rapidly than most bordering states and by mid-2014 were in decline (Chart 7). In Iowa and other states with concentrated corn production, farmland values also had retracted by 2014, but did not experience the same growth as Nebraska prior to softening. For example, from 2012 to 2014, annual changes in farmland values in Nebraska ranged from an increase of 40 percent to a decline of 1 percent. Over the same time, average gains in farmland values in bordering states slowed from an annual rate of 25 percent to 3 percent.

Agriculture’s Influence on the Nebraska Economy

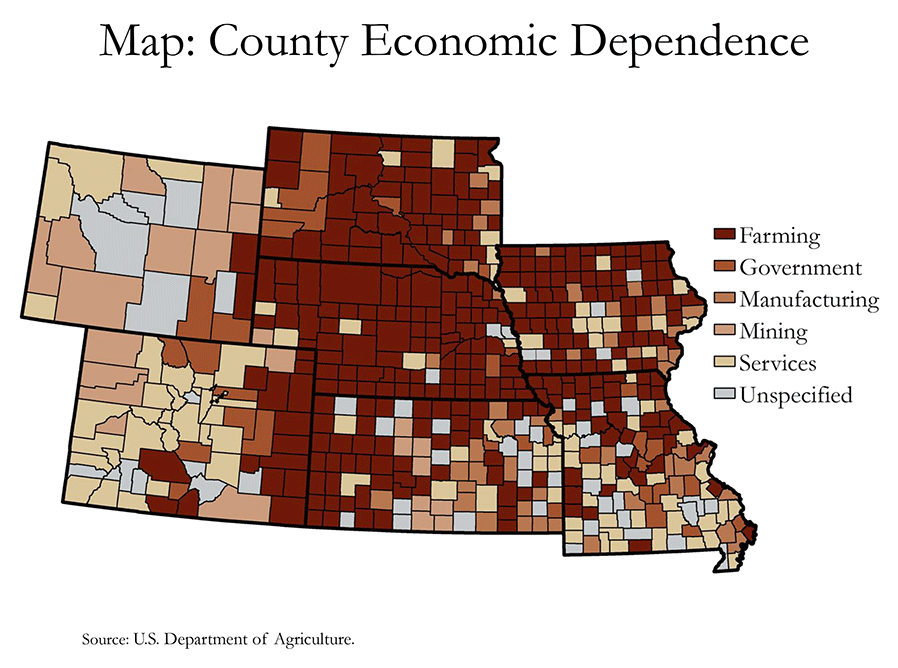

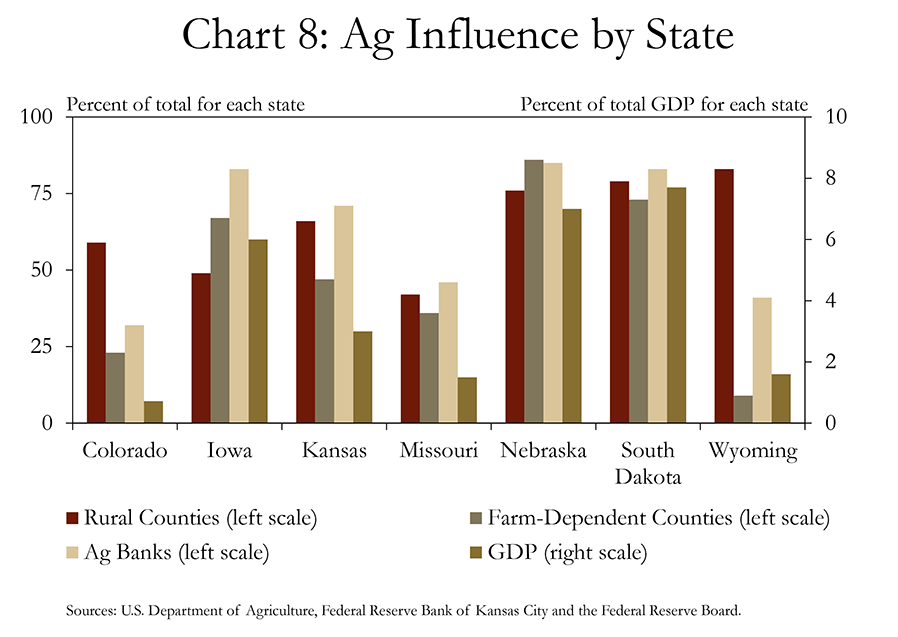

The relatively weaker outlook in Nebraska likely has been due to a greater dependence on farming. By county economic classification, Nebraska is nearly twice as dependent on agriculture as Kansas, the next most farming-dependent state in the Tenth District (Map).i By other measures, agriculture is an especially important industry to Nebraska when compared to U.S. states, including those that share a border with Nebraska. For example, Nebraska has more farm-dependent counties and agricultural banks than any state in the country.ii Nebraska also ranks second in agriculture share of GDP and third in proportion of rural counties (Chart 8).

Implications for Main Street

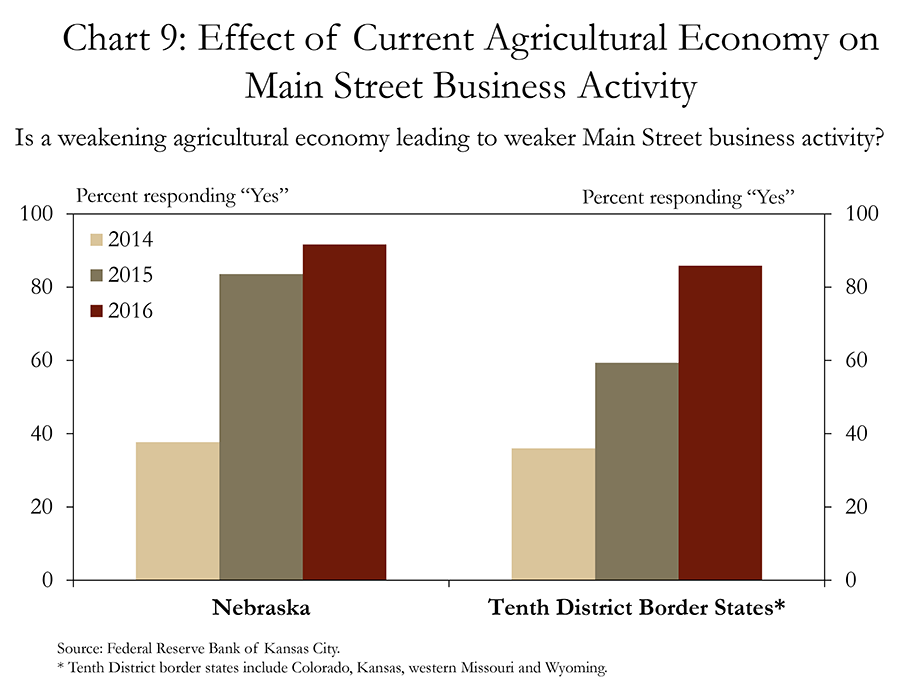

Nebraska’s dependence on farming makes the recent downturn in agriculture particularly concerning. Greater pessimism in the agricultural economy appears to be spilling into Main Street and causing general weakness in rural areas. In 2015, 84 percent of agricultural lenders in Nebraska responded that a weakening agricultural economy was leading to weaker Main Street business activity (Chart 9). In surrounding Tenth District states, only 59 percent of bankers indicated Main Street business activity was weaker due to the weakening agricultural economy. In 2016, the percentage of bankers in bordering states that reported weaker business activity grew, but the outlook for Main Street was still slightly more pessimistic in Nebraska.

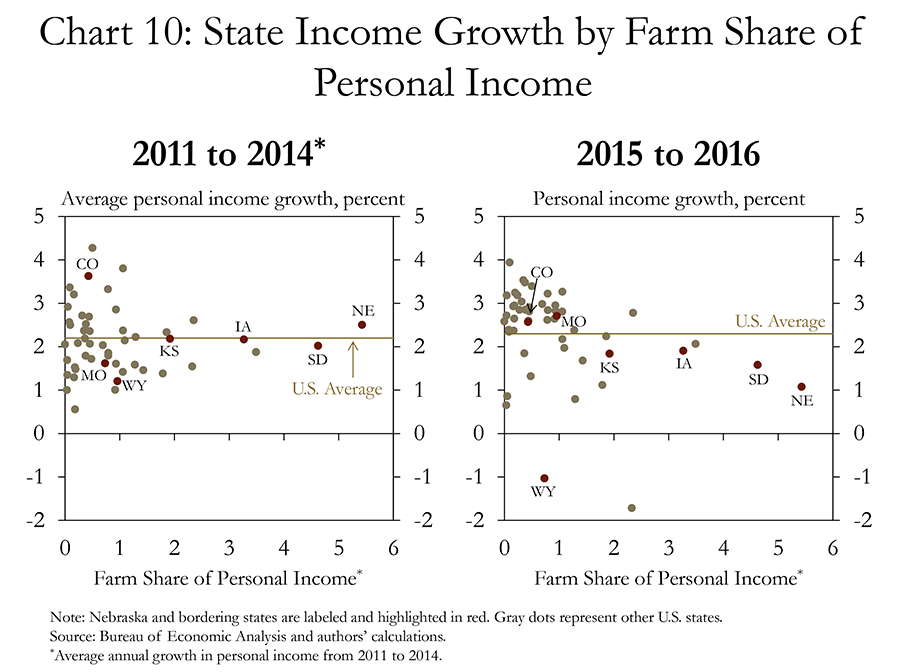

Alongside weaker Main Street business activity, the softening agricultural economy in Nebraska could be weighing on general economic indicators. Nebraska has the nation’s largest share of personal income contributed from farming at 5.4 percent. When commodity prices were relatively high from 2010 to 2014, Nebraska was 15th in the nation in growth of average personal income (Chart 10). From 2015 to 2016, commodity prices fell significantly, and personal income growth in Nebraska fell to the sixth worst in the country. In fact, the only states with lower growth in personal income were states that are most dependent on mining, a sector that also has experienced a significant slowdown.iii

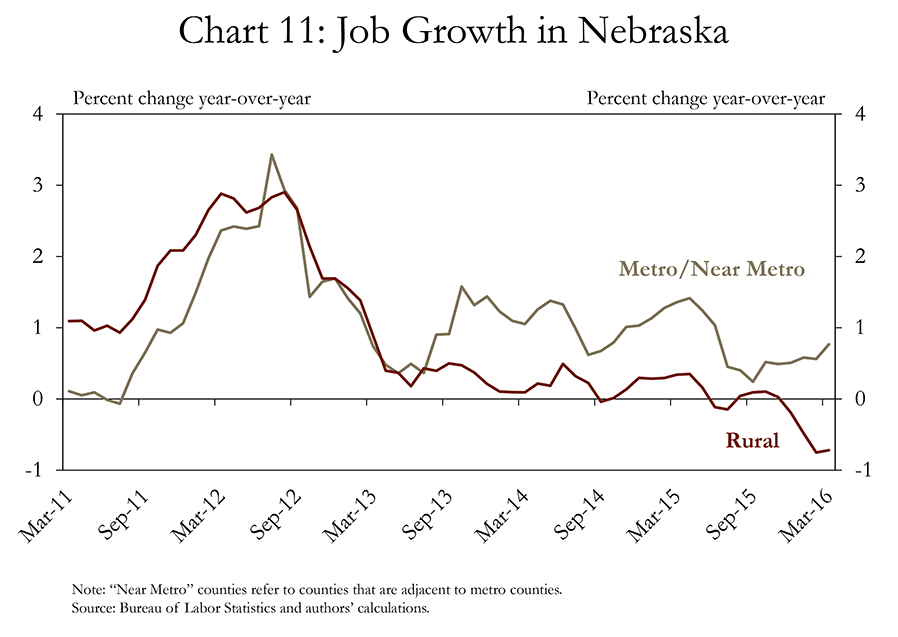

Intensifying stress from lower prices for agricultural commodities also has weighed on the growth of rural employment in Nebraska. Prior to 2013, job growth in rural areas was similar to or slightly higher than metro and adjacent areas (Chart 11). Conversely, job growth in rural areas since mid-2013 has slowed sharply. Lower job growth in 2013-14, followed by actual declines in 2015 and into 2016, corresponded closely with the drop in commodity prices and the subsequent downturn in personal/farm income and spending.

Conclusion

The recent downturn in prices for agricultural commodities has weighed heavily on Nebraska’s economy. Most of the counties in Nebraska are rural and/or dependent on farming. In addition, a large majority of Nebraska’s banks are considered agricultural. Although farming activities account for a relatively modest share of total personal income in the state, farming affects other important areas of the state economy, such as farm equipment manufacturing, agricultural services and food processing and retail. Consequently, the persistent, gradual and intensifying decline in farm income and credit conditions could be contributing to weaker Main Street business activity and lower job growth in rural areas. In addition, the weakness that first occurred in Nebraska has now become more evident in other states.

_______________________________________________________________

i According to the USDA, a county is dependent on farming if farm earnings account for an annual average of 25 percent or more of total county earnings or farm employment accounts for 16 percent or more of total employment.

ii We define agricultural banks as having greater than or equal to 15 percent of their total loans in farm loans.

iii Mining includes oil, coal and natural gas production.