Agricultural credit conditions throughout the Tenth District continued to deteriorate in the second quarter of 2016 as farm income remained subdued. Repayment rates for farm loans softened again and bankers reported a modest increase in both loan repayment problems and the number of loan applications that were denied. Weak farm income and worsening credit conditions also continued to trim farmland values, and respondents in general indicated they expect farmland values to trend lower in the months ahead.

Farm Income

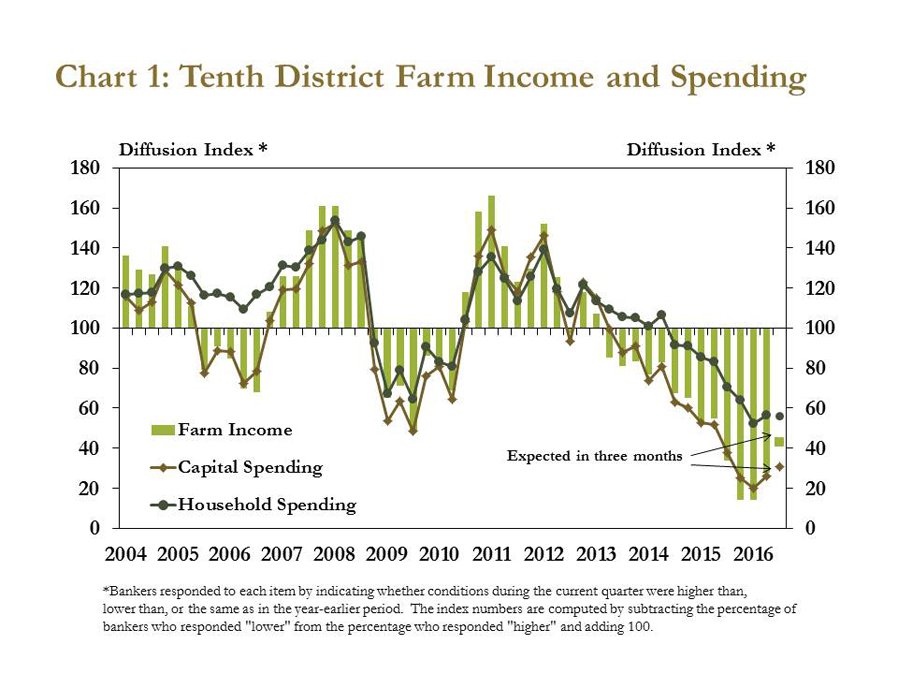

Respondents to the Tenth District Survey of Agricultural Credit Conditions indicated farm income in the quarter continued to tighten. Nearly 75 percent of surveyed bankers reported farm income was less than a year ago, although the percent of bankers that reported weaker farm income declined slightly from the first quarter (Chart 1). Respondents also noted that agricultural producers continued to reduce capital and household spending as profit margins generally remained weak.

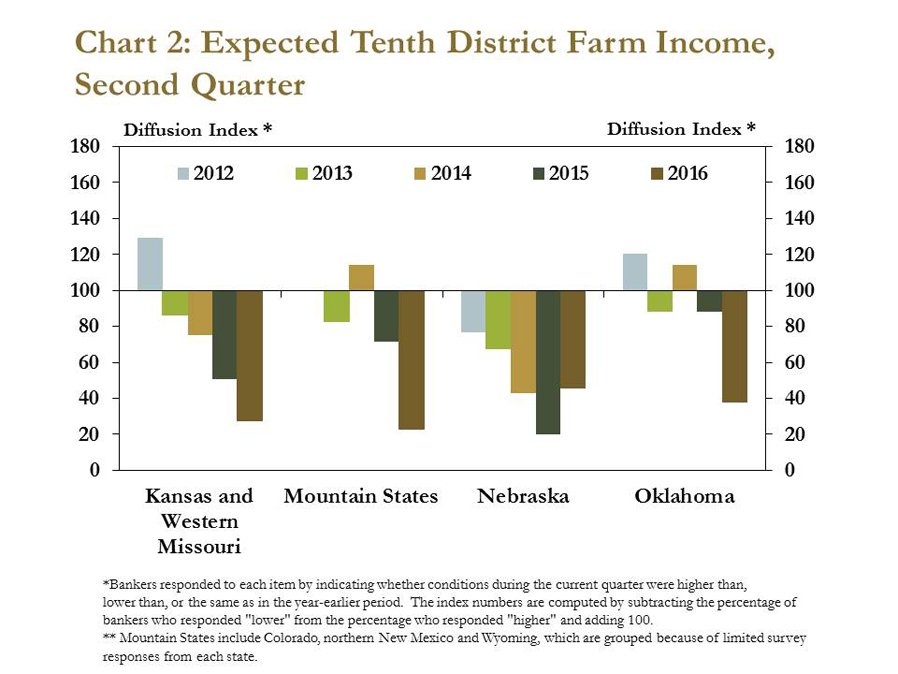

Bankers also indicated they expect farm income to remain weak in the third quarter. Similar to last year, a significant number of bankers in each District state expect farm income in the third quarter to be less than a year earlier (Chart 2). They also expect the rate of decline to be sharpest in the Mountain States and Oklahoma, which are relatively more dependent on income from wheat, cattle and energy production than other parts of the District. As the outlook in these three sectors has become increasingly downbeat, more bankers in those regions expect farm income to decline further.

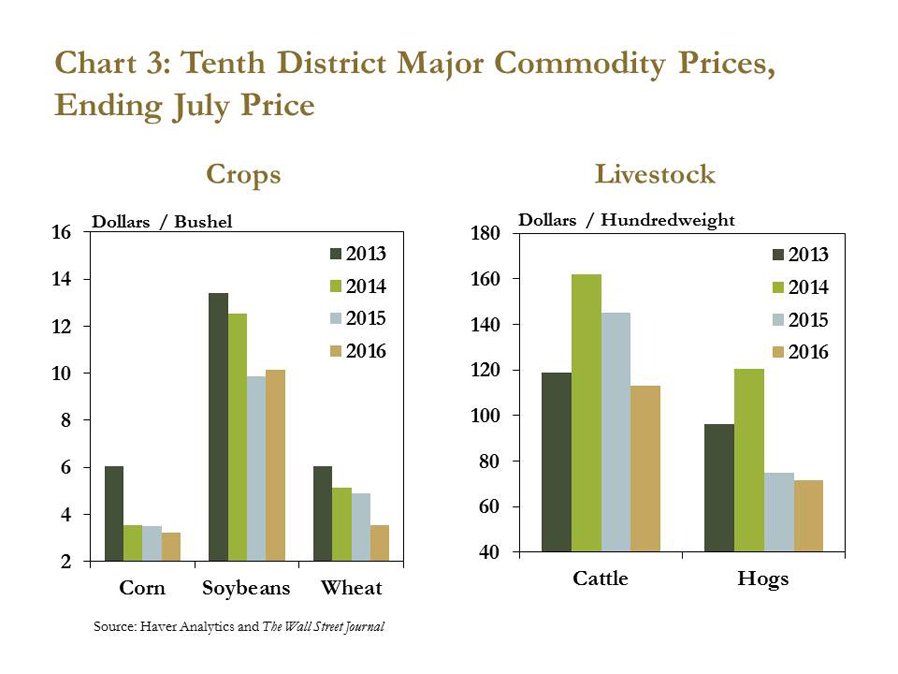

Low commodity prices continued to be the primary driver of reduced farm income. Prices for most of the top commodities produced in the Tenth District have fallen from a year ago and are well below prices of recent years (Chart 3). For example, at the end of July 2016, corn and soybean prices were 47 percent and 24 percent less, respectively, than the same period in 2013. Cattle and hog prices also were lower than a year ago and remained lower than in 2013.

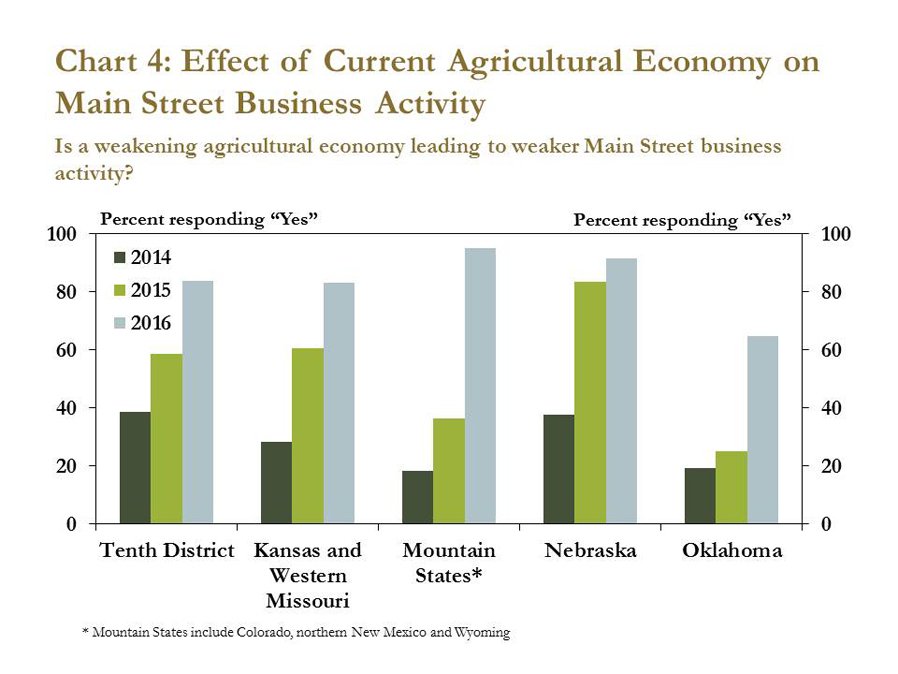

Weaker farm income has continued to have an adverse effect on the District’s Main Street businesses. Almost 85 percent of bankers noted that the weakening farm economy has reduced Main Street business activity, up from about 60 percent last year and just under 40 percent in 2014 (Chart 4). The change in spillover effects from the farm economy to Main Street businesses was most significant in the Mountain States and Oklahoma, regions with a stronger relative dependence on the livestock and energy sectors. However, a large number of bankers in Nebraska also continued to report that a weaker farm economy was affecting businesses in their region at a pace similar to last year.

Farm Loan Demand and Credit Conditions

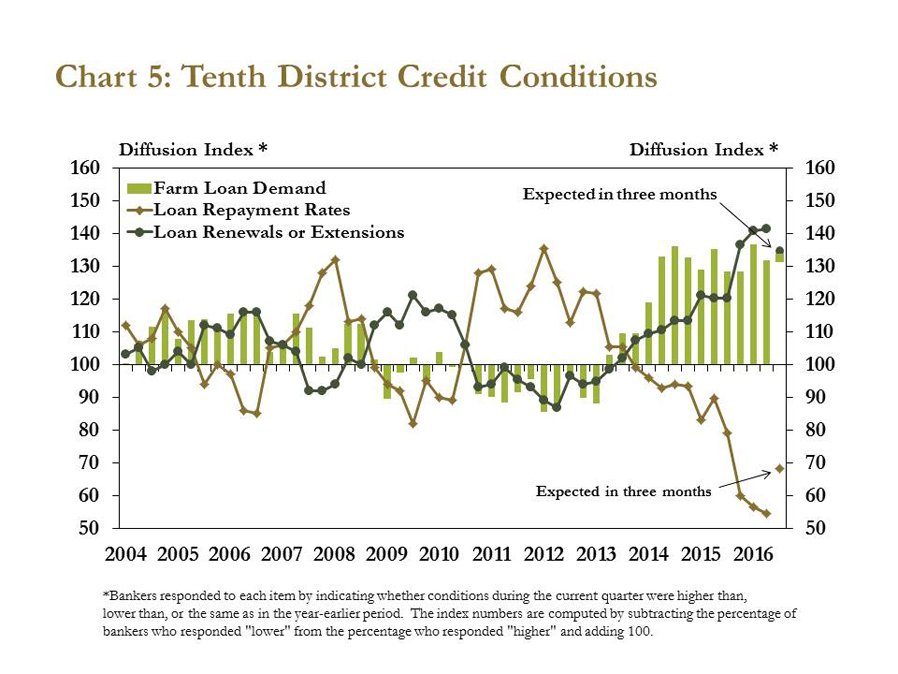

Persistent declines in farm income in the District have continued to affect agricultural credit conditions. Demand for non-real estate farm loans and loan renewals continued to climb in the second quarter with additional increases expected in the third quarter (Chart 5). As noted in the Kansas City Fed’s most recent Agricultural Finance Databook, the rising demand for farm loans has been driven primarily by the need to finance short-term operating expenses as profit margins have remained weak.

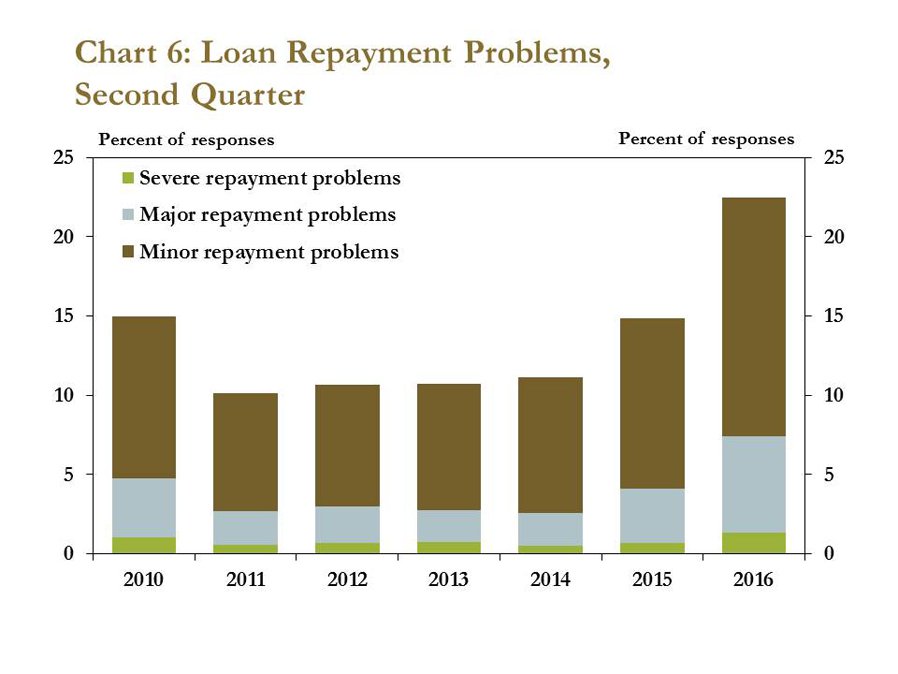

Slimmer profit margins also have pulled down the rate of loan repayments. Almost half of all respondents reported that loan repayment rates in the second quarter were lower than a year ago. In addition, the severity of repayment rate problems has increased slightly over the past year. In 2016, more than 7 percent of farm loans had major or severe repayment problems, a relatively large increase from the 2011-13 average of less than 3 percent (Chart 6). The share of farm loans with at least minor repayment problems was approximately 22 percent in the second quarter, and has trended up since 2014.

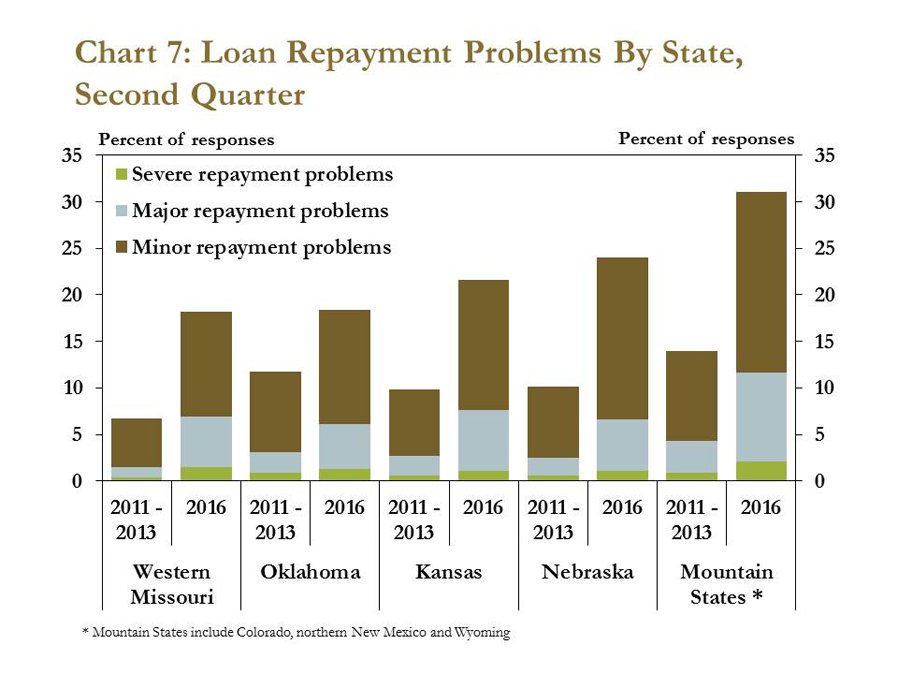

Evidence of repayment problems also has surfaced at the state level. The share of farm loans with identified repayment problems has increased to at least 18 percent in all states (Chart 7). In the Mountain States, more than 30 percent of farm loans had some type of repayment problem, a jump of 17 percentage points from the 2011-13 average. Loan repayment problems also increased in other District states from the 2011-13 average, reflecting the effects of prolonged weakness in farm income throughout the District.

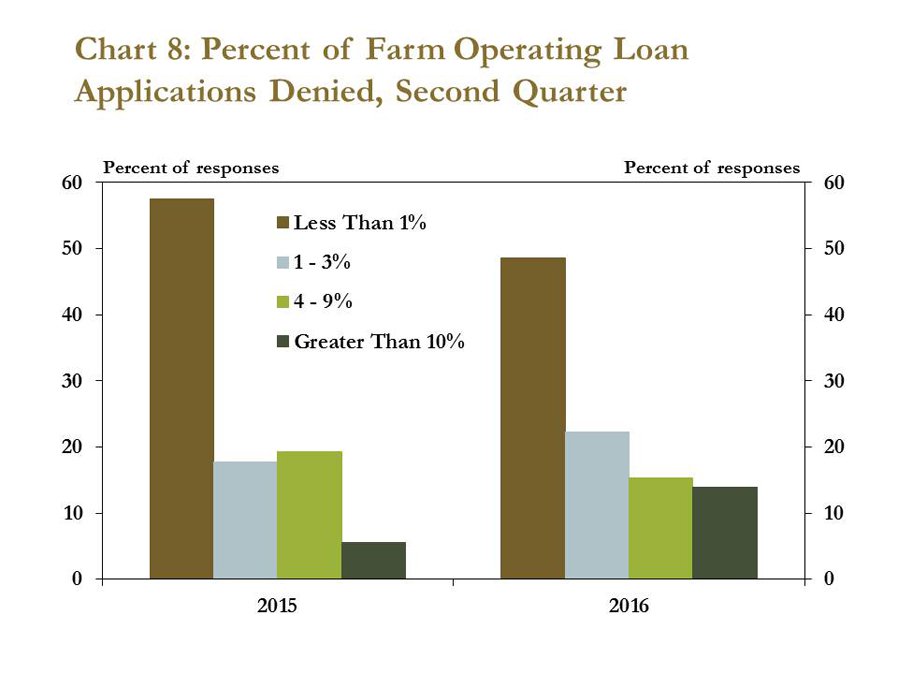

In response to a weakening farm economy and increased problems with loan repayments, bankers reported an increase in the share of loan applications that were denied in the second quarter. In 2016, almost 15 percent of bankers reported that they denied more than 10 percent of applications for farm operating loans (Chart 8). By comparison, only 5 percent of bankers indicated they had denied loan applications at this rate in 2015. Although District bankers continued to report that ample credit was available for borrowers who are in a strong financial position, the higher rate of loan denials suggests the number of farm borrowers who are less creditworthy has increased over the past year.

Farmland Values

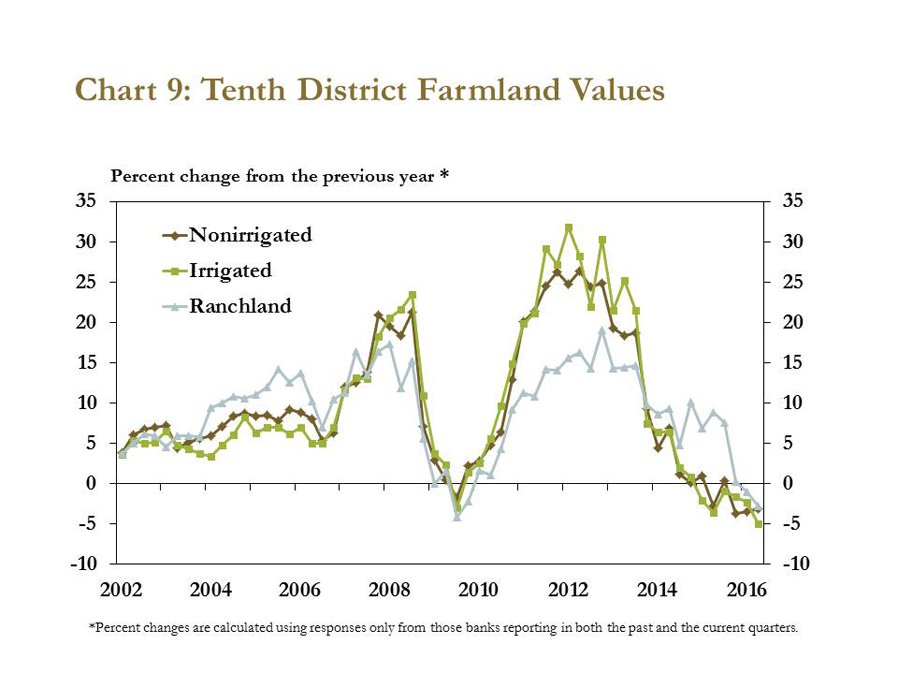

Weakening farm income and deteriorating credit conditions continued to pressure farmland values lower. Values of nonirrigated and irrigated cropland declined 3 percent and 5 percent, respectively, from a year ago. Ranchland values also declined 3 percent, continuing the downward trend of recent quarters (Chart 9). From 2002 to 2014, the value of both irrigated and nonirrigated cropland declined in only one quarter (the third quarter of 2009). As of the second quarter, however, irrigated cropland values have declined in each of the past six quarters and nonirrigated cropland values have declined in four of the past six quarters.

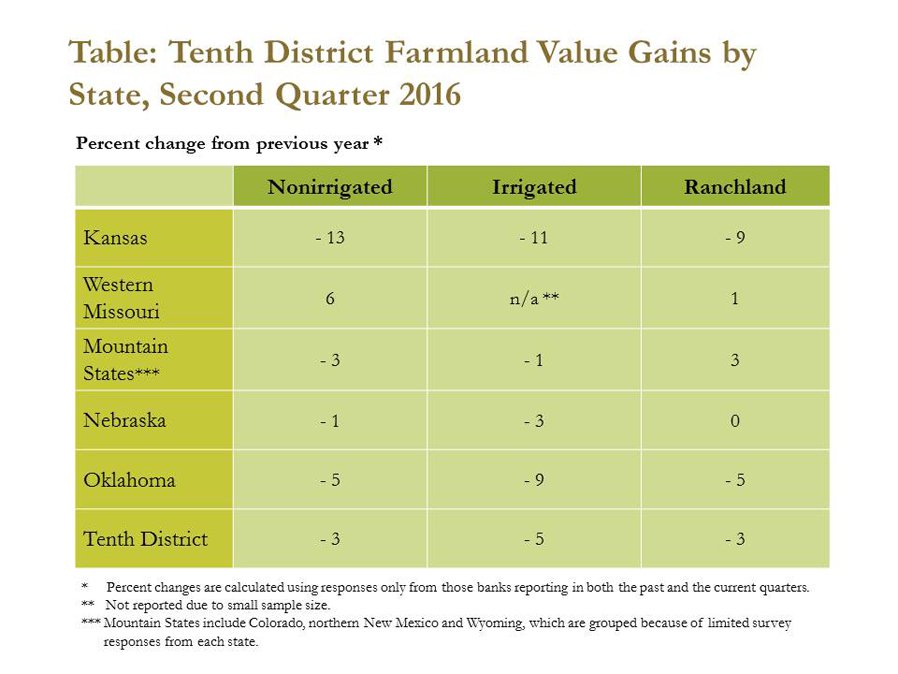

In general, cropland values also have trended lower in each District state (Table). Declines in cropland values were most significant in Kansas and Oklahoma, likely due to sustained weakness in profit margins associated with wheat and cattle production and potential spillover effects from difficulties in the energy sector. The declines in Kansas cropland values were, in fact, the largest year-over-year declines in any state during the downturn of the past two years. Cropland values in Nebraska fell for an eighth consecutive quarter, and the 5 percent decrease in irrigated cropland values for the District was the largest decrease in 29 years.

Many bankers continued to anticipate further declines in farmland values in the months ahead. Specifically, more than 30 percent of bankers expect the values of all types of farmland to decline in the next quarter while less than 2 percent expect an increase. When asked to rank factors contributing to the changes in farmland values, the majority of bankers continued to rank the overall level of farm wealth as the most significant. However, bankers also expect farm income to have a more significant effect this year in the adjustment of farmland values than in previous years, suggesting that reductions in cash flow may continue to weigh on farmland values.

Looking Ahead

Low commodity prices have continued to drag down farm income and weaken agricultural credit conditions. At the end of the second quarter, crop prices appeared poised to remain low alongside growing expectations of a strong fall harvest. Borrowers without sufficient liquidity, substantial net worth or large borrowing bases may find it increasingly more difficult to attain financing if their creditworthiness continues to decline. Moderating farmland values may also add pressure to borrowers and banks that rely on highly leveraged farmland as collateral. Despite these concerns, farm loans in the second quarter that were significantly past due or non-accruing remained slightly below recent averages amid a general, gradual downturn in the farm economy.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City or the Federal Reserve System.