Nebraska’s economy has continued to move forward, but not all parts of the state have been moving at the same pace. Despite some recent softening, metro areas have been driving most of the gains in Nebraska’s economy over the past year, as rural areas have slowed alongside a softer farm economy. Moreover, although Omaha and Lincoln have continued to grow, disparities in economic conditions have persisted within those metropolitan areas. For a clearer picture of Nebraska’s economic health, however, it is important to remember that there are pockets of less-robust activity than what statewide figures show.

Economic and Labor Market Outlook

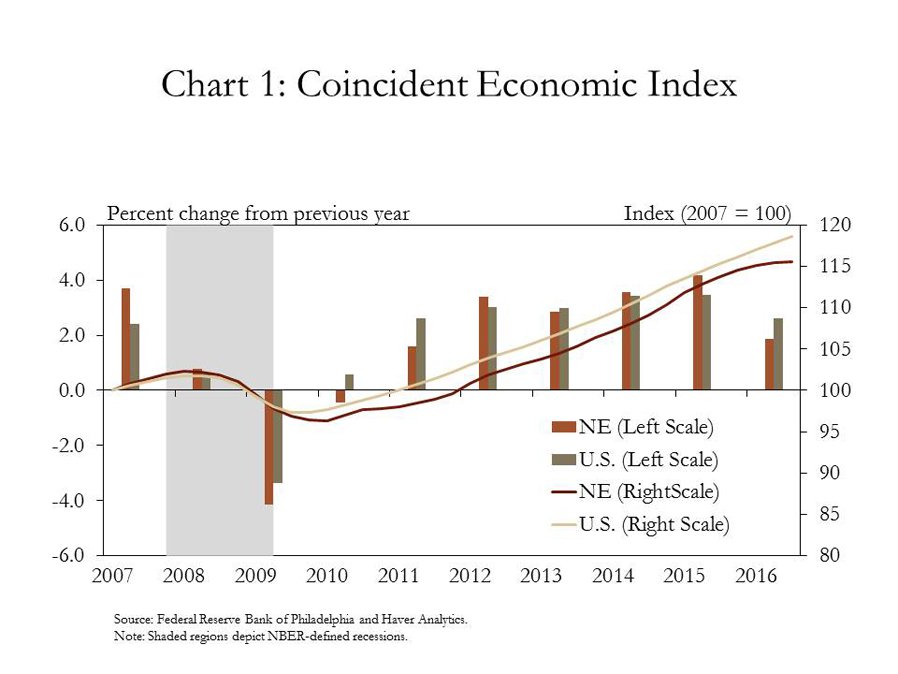

Economic activity in Nebraska, which in recent years has seen continued year-over-year growth, has slowed in the last year. Following the 2008-09 recession, when economic activity in both the United States and Nebraska slowed sharply, the economy of both the nation and the state has expanded steadily (Chart 1). The Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia’s coincident economic index, which seeks to capture broad trends in economic conditions, shows conditions in Nebraska have improved each year since 2009. From 2012 through 2015, growth in the index averaged 3.5 percent per year. Although the increase continued through the third quarter of 2016, it slowed to 1.9 percent.

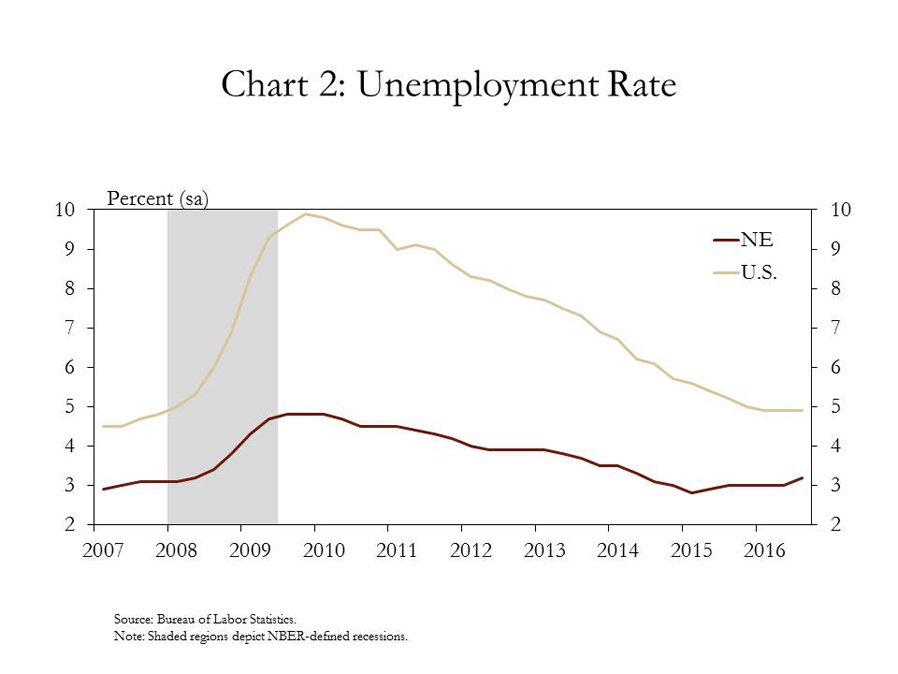

Similar to the steady gains in economic activity, labor markets in Nebraska also have improved significantly since the recession. Nebraska’s unemployment rate peaked at 4.8 percent during the Great Recession, but has trended lower since then (Chart 2). After touching a post-recession low of 2.8 percent in early 2015, the state’s unemployment rate has edged higher to 3.4 percent. Although the increase is of note, Nebraska’s unemployment rate still remains among the nation’s lowest, more than a full percentage point below the national rate.

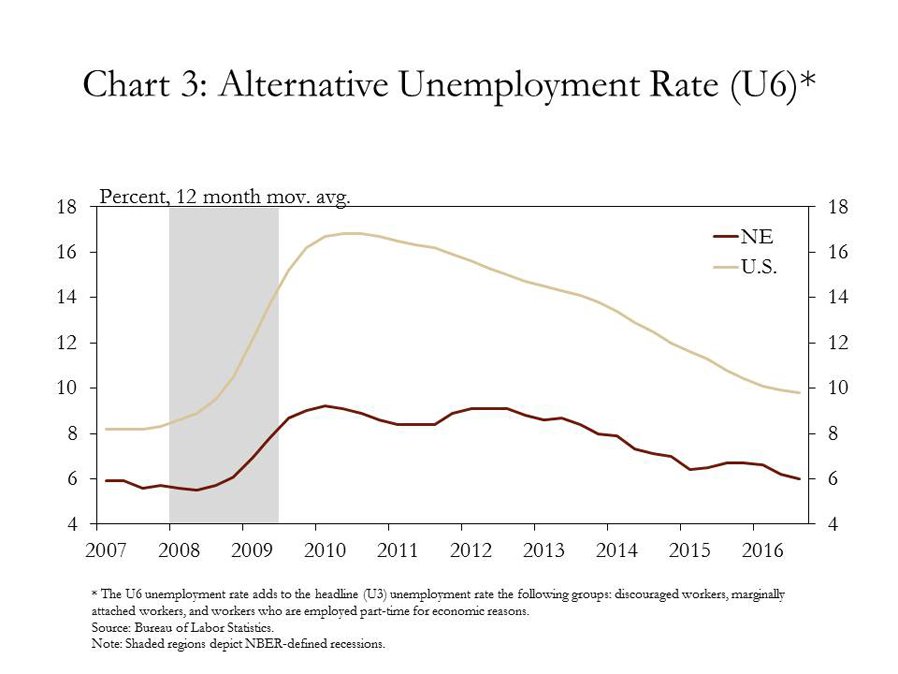

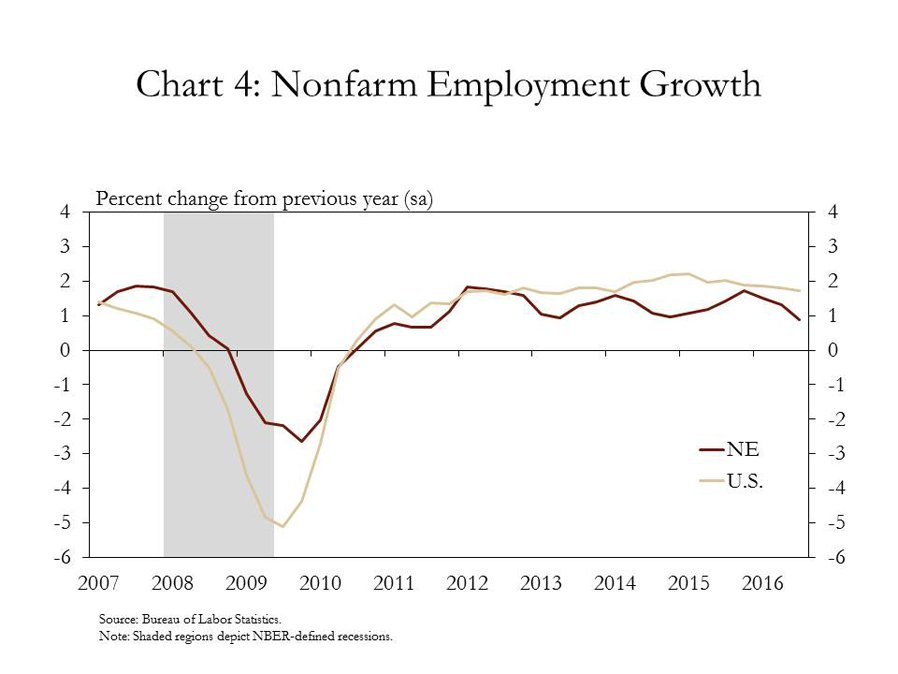

Other indicators also show steady gains in the health of Nebraska’s labor market. The state’s U6 unemployment rate, a broader measure of unemployment than the headline rate of 3.4 percent, also shows consistent improvements (Chart 3). Since its peak following the recession, Nebraska’s U6 unemployment rate has dropped from 9.2 percent to 6 percent. Moreover, while job growth in Nebraska has slowed in recent quarters, the state has added jobs in 25 consecutive quarters (Chart 4).

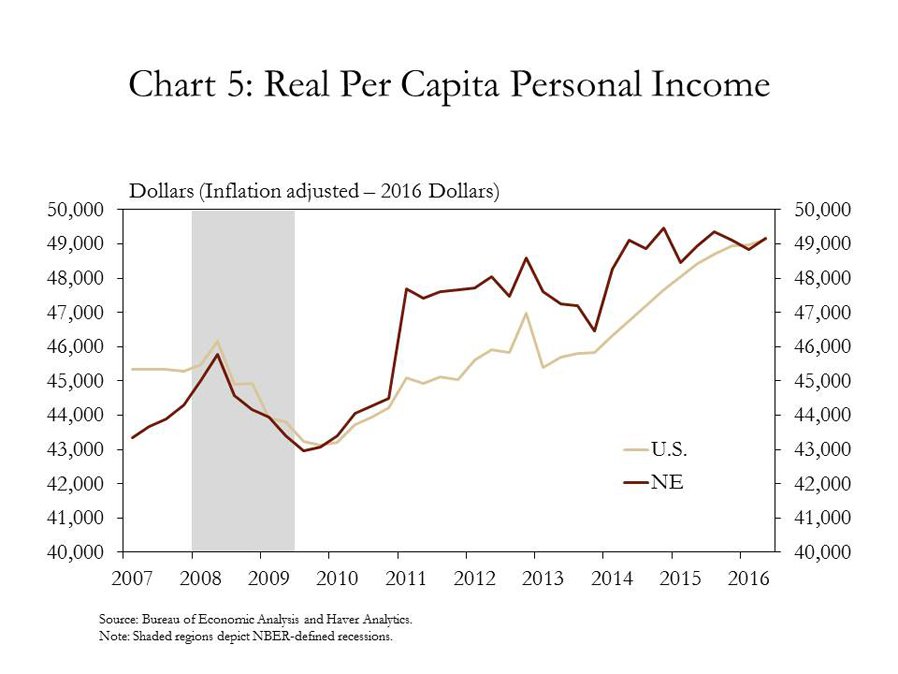

In addition to broad gains in economic activity and employment measures, personal income in Nebraska has also continued to rise, mirroring that of the nation. Through the second quarter of 2016, real per capita personal income in Nebraska was almost identical to that of the nation at $49,170 (Chart 5). In fact, since 2009, per capita income in Nebraska has increased 13 percent, even after adjusting for inflation.

Metropolitan Area Outlook

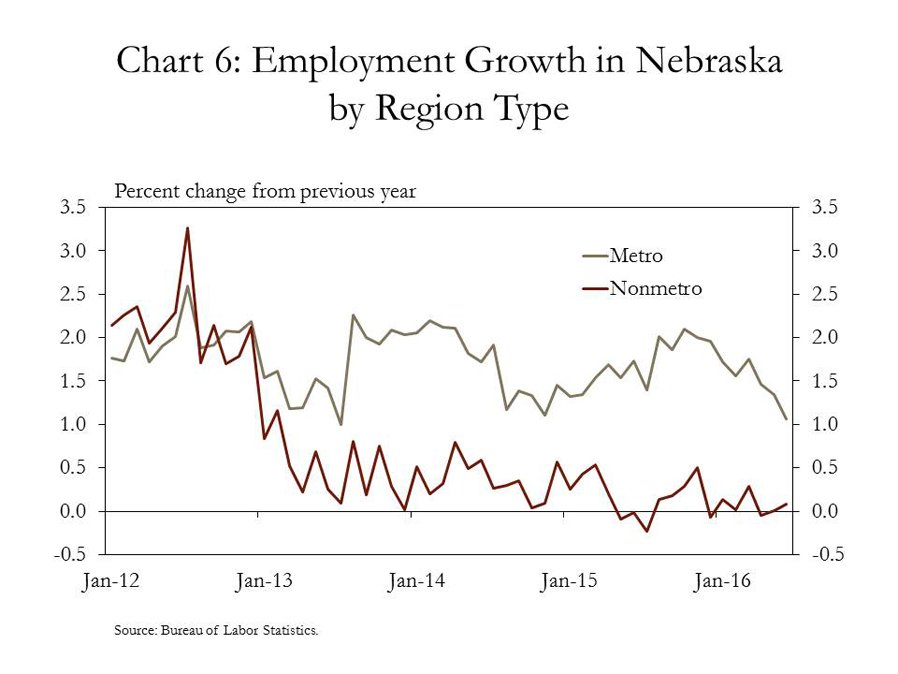

As discussed in a previous edition of The Nebraska Economist, economic growth in Nebraska in the past year largely has been driven by gains in the state’s metropolitan areas. Prior to 2013, nonmetro job growth in Nebraska was similar to that of the rest of the state (Chart 6). Since 2013, however, job growth in the state’s metro areas has outperformed nonmetro regions. In fact, over the past year, job growth in nonmetro Nebraska has flattened while growth in the state’s more populous areas has continued to grow by more than 1 percent.

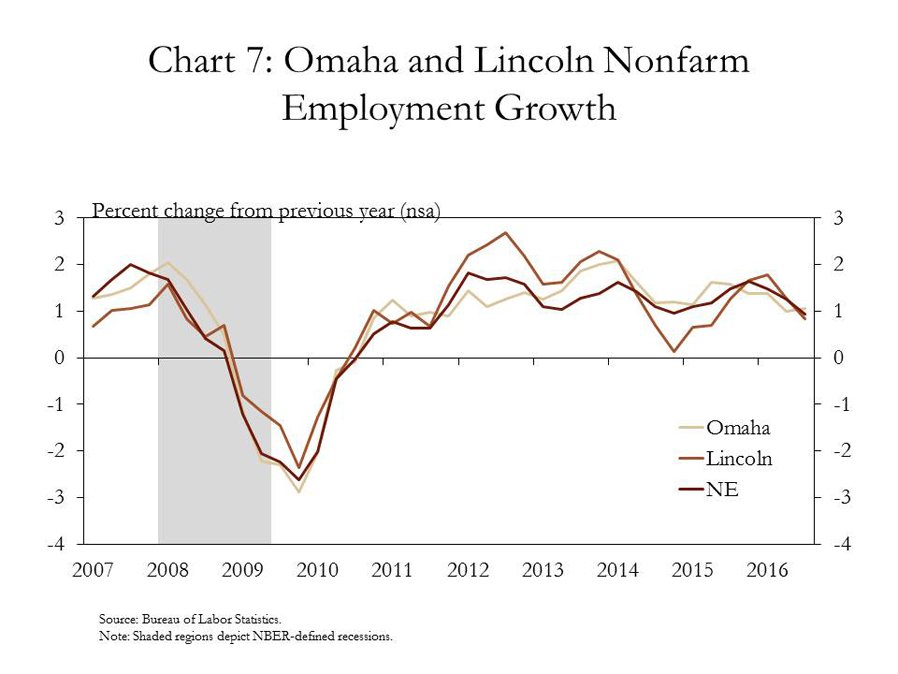

More specifically, strength in Omaha and Lincoln has continued to drive employment growth in Nebraska. Over the past five years, job growth in Nebraska has averaged 1.3 percent. Over that time, job growth has averaged 1.4 percent in Omaha and 1.5 percent in Lincoln (Chart 7). The gains in Omaha and Lincoln largely have been driven by ongoing increases in the leisure and hospitality industry as well as education and health services. In Omaha, employment in the leisure and hospitality industry has increased 2.6 percent year-to-date, when compared with last year. In Lincoln, the education and health services industry has increased employment 2.0 percent from a year ago.

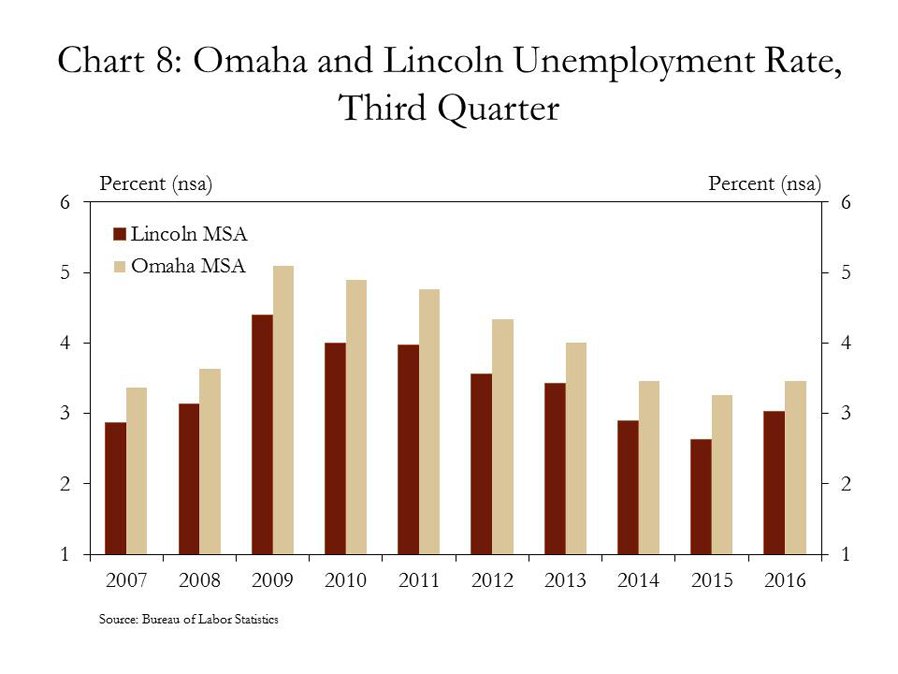

Similar to Nebraska as a whole, job gains in Omaha and Lincoln have pushed unemployment rates in those areas to near their pre-recession marks, despite a slight increase recently. In the third quarter, Omaha’s unemployment rate was 3.5 percent, up modestly from a year ago, but similar to the 3.4 percent rate in 2007 (Chart 8). Lincoln’s unemployment rate increased from 2.6 percent a year ago to 3.0 percent in the third quarter, but compares with a rate of 2.9 percent in 2007.

Outlook within Metros

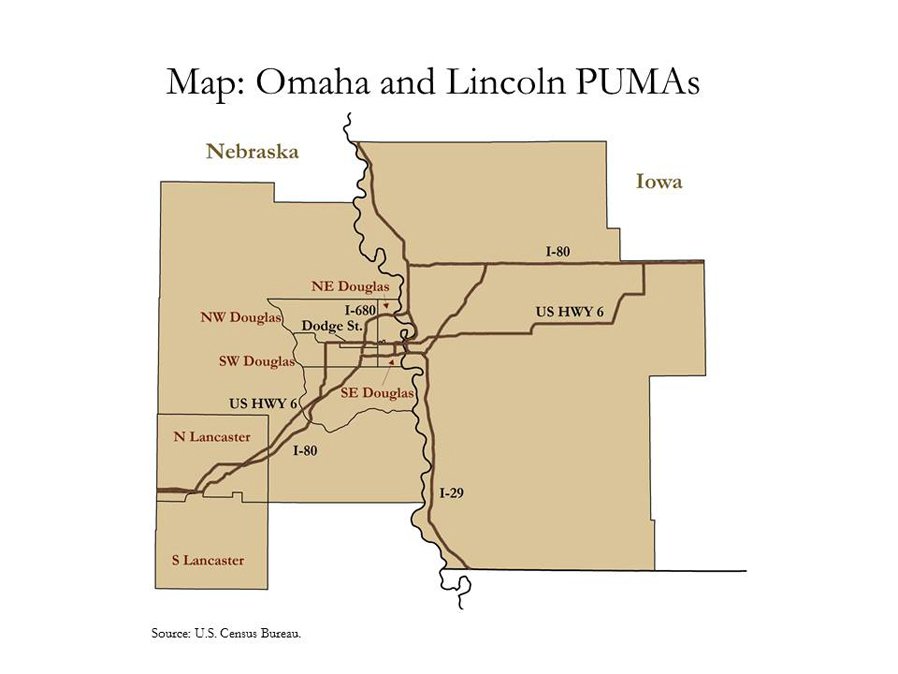

In addition to the growing disparity between metro and nonmetro Nebraska, economic conditions have varied significantly even within Omaha and Lincoln. The Omaha metro area consists of five counties in Nebraska and three in Iowa, but can be divided into a different set of boundaries, based on census tracts, to compare economic conditions across regions with similar populations, but within a given county (Map). These regions are referred to as Public Use Microdata Areas (PUMAs) and consist of groupings of census tracts, where each PUMA is designed to include a minimum of 100,000 people.

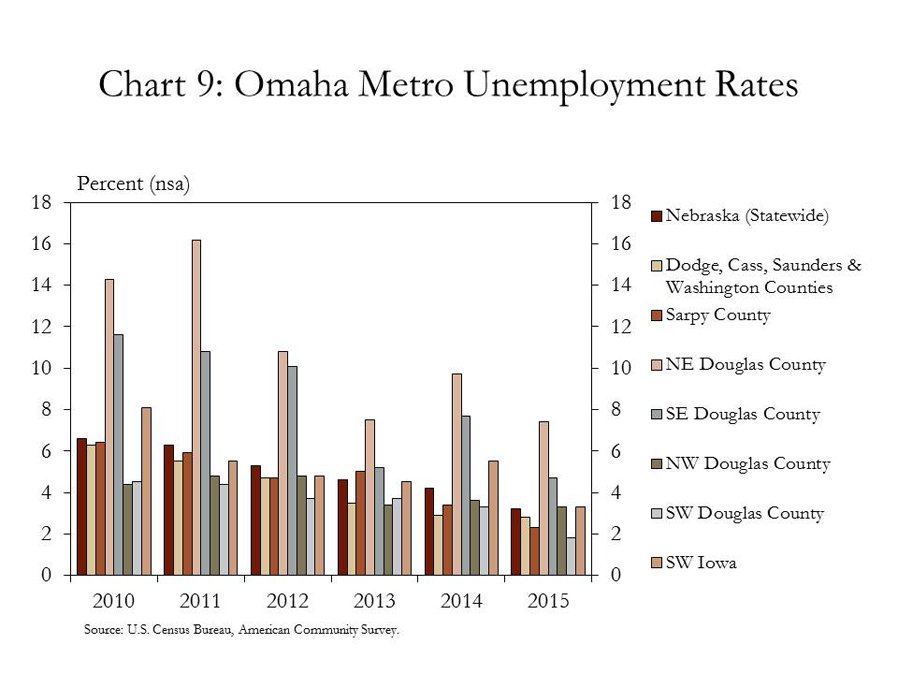

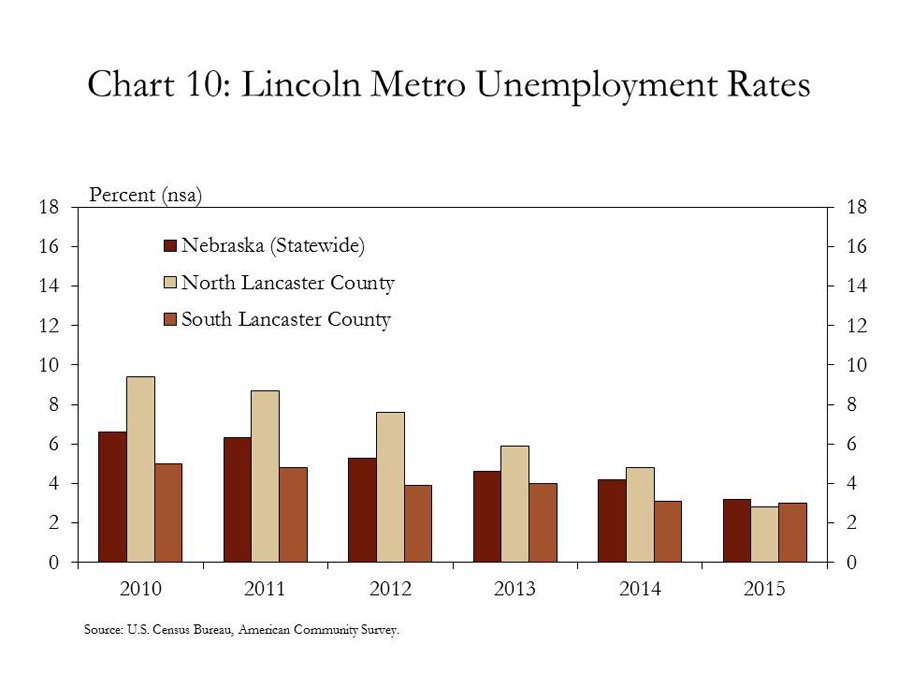

In both Omaha and Lincoln, unemployment rates have varied significantly across PUMAs, especially within Douglas County in Omaha. The unemployment rate in northeast Douglas County has declined considerably since its recent peak of more than 16 percent in 2011. Still, at 7.4 percent in 2015 (the most recent data available), it remained sharply higher than the mere 1.8 percent of southwest Douglas County (Chart 9). In Lincoln, the unemployment rate was much higher in north Lancaster County following the recession, but the gap between north and south has narrowed since 2010 (Chart 10).

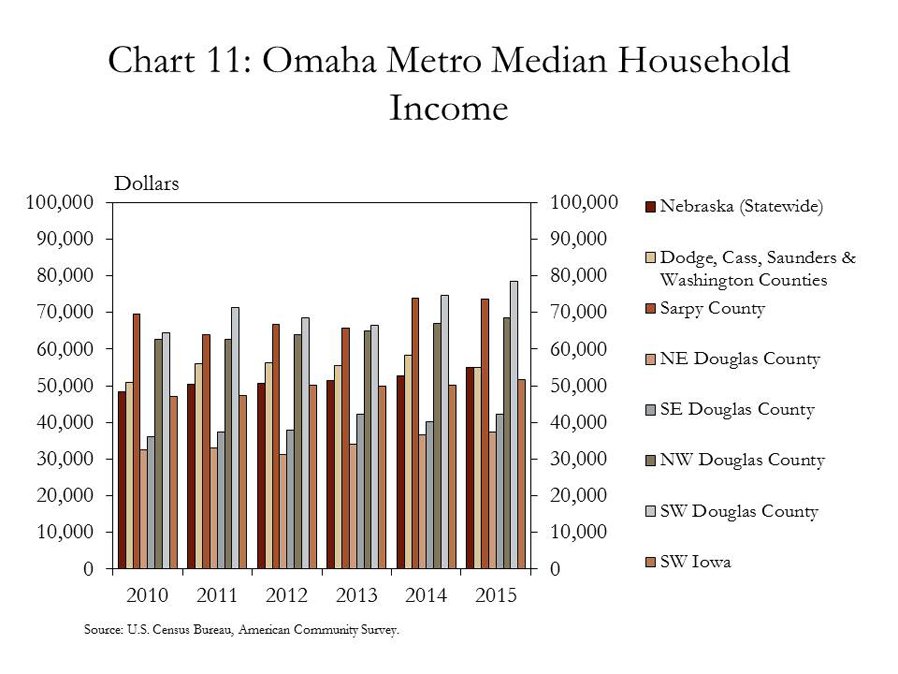

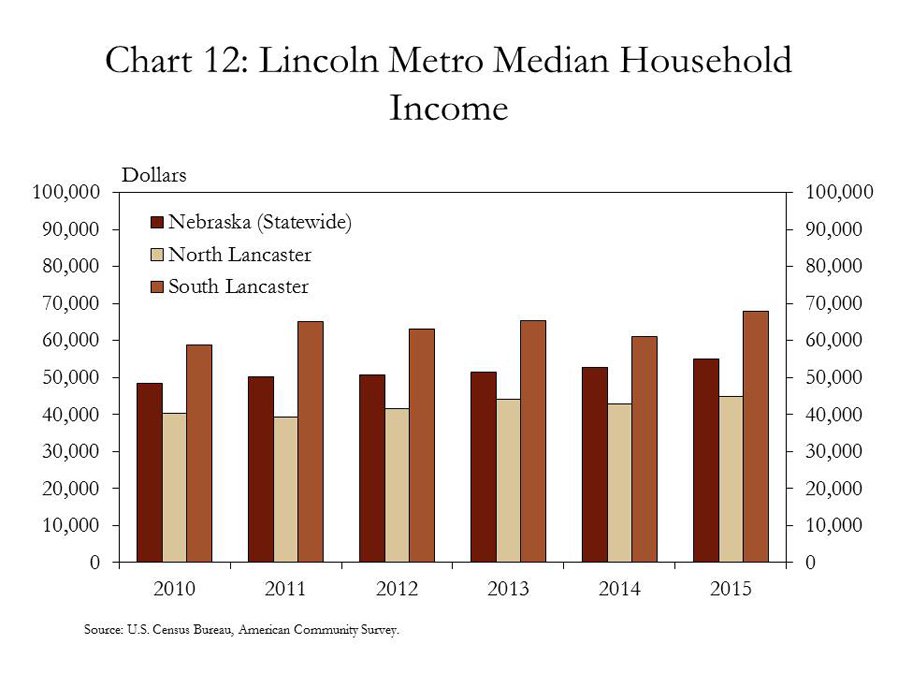

In addition to local disparities in employment, disparities in personal income within the metro regions of the state also have persisted despite the state’s general economic success. Median household income in southwest Douglas County, for example, was more than twice that of northeast Douglas County in 2015 (Chart 11). That gap has held steady through the economic recovery following the 2008–09 recession. In Lincoln, despite a narrower gap in unemployment rates, the gap between personal income for households in north Lancaster County and south Lancaster County also has remained generally the same at about $20,000 annually (Chart 12).

Conclusion

Driven by ongoing strength in Omaha and Lincoln, Nebraska’s economy has remained strong despite some persistent disparities that have continued, and in some cases intensified, during the recent recovery. Economic activity in Nebraska’s metro areas has propelled the state forward, even as much of the rest of the state has grappled with a weaker agricultural economy. And despite the contributions of the state’s metros, some disparities also have persisted within Omaha and Lincoln themselves. These ongoing disparities within the state, and within the state’s metropolitan areas, should be acknowledged when assessing the overall strength of the state’s economy.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City or the Federal Reserve System.