By External LinkDell Gines, Senior Community Development Advisor, and External LinkChad Wilkerson, Oklahoma City Branch Executive_

One hundred years ago, on May 31 and June 1, 1921, violence erupted in the streets of north Tulsa. An estimated 150-300 deaths occurred during the destruction of the Greenwood area, known as “Black Wall Street.” In addition to the loss of life, the Tulsa Race Massacre destroyed a previously thriving local economy. And while the devastated community rebuilt many of their businesses over time, the economies of Greenwood and other primarily Black communities of north Tulsa have continued to experience economic challenges into the 21st century. This edition of the Oklahoma Economist reviews the history of Black Wall Street, its economy in recent years and current efforts that hold promise for its future.

The History of Black Wall Street

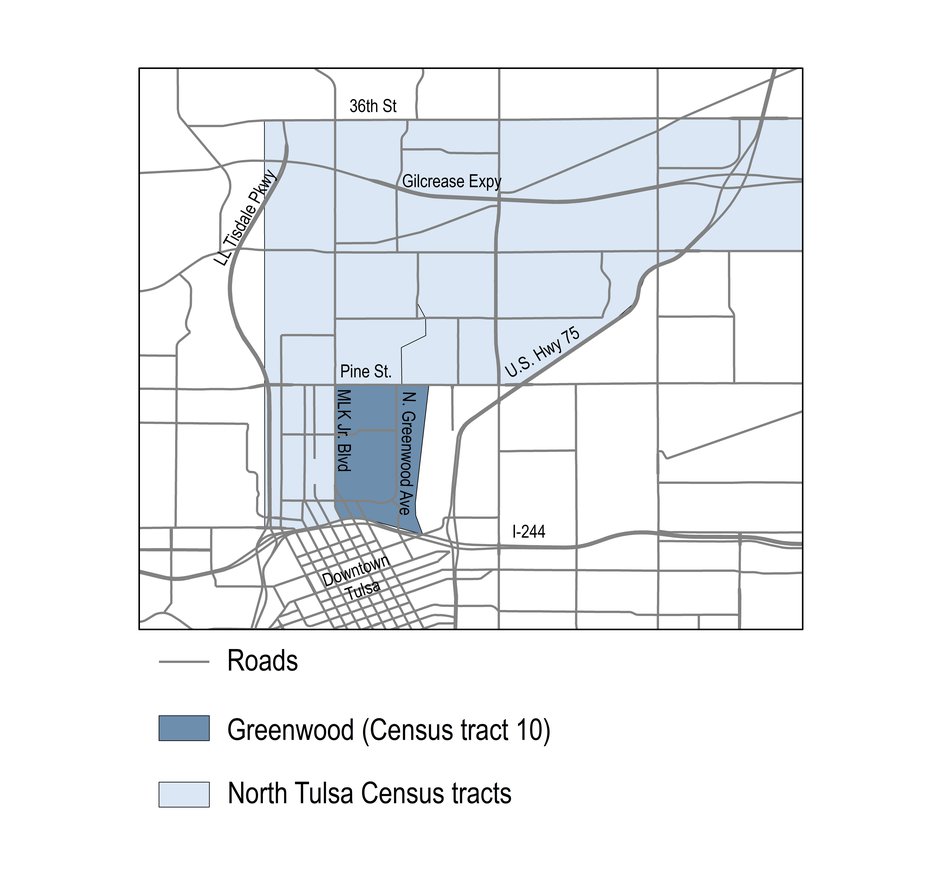

Black Wall Street long has been a symbol of economic hope and success for the Black community in the United States. Discussion about economic revitalization in Black communities often centers on creating the “next Black Wall Street.” This is due to the entrepreneurial spirit demonstrated by Greenwood residents in the face of racism and segregation in the early 1900s. However, outside the Black community, until recently there has been little discussion nationally about Tulsa’s historic Greenwood District (Map 1).

Map 1: Greenwood and north Tulsa

Events of the late 1800s and early 1900s helped set the stage for Black Wall Street. The oil boom in Tulsa in the early 1900s led to a significant increase in population, wealth and opportunity. As Tulsa began to attract more industry and commerce, Black Americans saw it as a setting for significant opportunity. Even before the oil boom, Oklahoma was seen as a land of potential for many Black Americans. Land runs in the late 1800s enabled Black Americans to acquire land and build homes._ By the early 1900s, of the estimated 50 all-Black townships in the United States, 20 were in Oklahoma._

During this period an enterprising Black man and founder of Black Wall Street, O.W. Gurley, sought to take advantage of Tulsa’s rapid economic growth. Gurley was a former teacher and postal worker born in Alabama and raised in Arkansas. Believing that the South never would give him the opportunities he was seeking, Gurley moved to Perry, Oklahoma, and opened a general store. Seeing opportunities in Tulsa, Gurley sold his store and purchased 40 acres of land in north Tulsa in 1906. In time, this area became known as the Greenwood District and eventually was dubbed Black Wall Street. Gurley’s intent for Greenwood was to establish a community led and run by enterprising Black Americans. After establishing the first store in Greenwood, a grocery, Gurley parceled and sold much of his land to other Black entrepreneurs and developers for various ventures.

Both Tulsa and Black Wall Street grew rapidly. The Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921 estimated the Tulsa population at about 10,000 in 1910, and that it rose sharply over the next decade to over 100,000._ By 1920, 12.3% of Tulsa’s population was Black._ The economy of Black Wall Street also grew so fast and became so robust that it became the talk of Black leaders across the nation, including Booker T. Washington. Upon visiting the Greenwood District, Washington called it “Negro Wall Street.” Eventually it became known as Black Wall Street.

While Gurley was one of the most significant entrepreneurs of the pre-1921 Black Wall Street era, other successful Black entrepreneurs emerged. Among them was J.B. Stradford, considered a co-creator of Black Wall Street. Stradford built the area’s first hotel, said to have been the finest in Tulsa. Simon Berry created a transportation network that included car rides and a bus line, and chartered private planes to fly oil barons into Tulsa. And the Williams family built the Dreamland Theater and several other businesses._ In the American Journal of Economics and Sociology article titled “The Destruction of Black Wall Street: Tulsa’s 1921 Riot and the Eradication of Accumulated Wealth” the authors share that:

The 1920 census recorded a multitude of African-American-owned businesses in the community, including billiard halls, clothing stores, music shops, furniture stores, confectionaries, meat markets, hotels, restaurants, and a movie theatre. According to the 1921 city directory, Greenwood comprised 191 businesses. It was also home to a library, two schools, a hospital, and two newspapers._

This economic growth was driven by a community-centered vision of mutual support and, in part, by the segregated nature of Tulsa. Many of the newly wealthy Tulsans hired Black employees from Greenwood for housekeeping and other service-based jobs. Because of the limited ability to shop in Tulsa’s white-owned stores, plus the desire to support their community, employees would purchase from the Black businesses in Greenwood. These businesses in turn made purchases from other businesses and hired residents of Black Wall Street, supporting the community’s economic growth and prosperity.

While wealthy Black entrepreneurs like Gurley were able to use banks owned by non-Blacks, many other local entrepreneurs found it difficult to obtain loans to support their business growth as the area had no banks owned by Blacks. In keeping with his community vision, Gurley and other large business owners like Stradford often would lend to other Black entrepreneurs in Greenwood. This helped continue to spur the economic growth of Black Wall Street. According to the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City’s forthcoming book A Great Moral and Social Force: A History of Black Banks, Stradford:

… was an especially strong believer in the idea of using a community’s pooled resources as the fuel to drive its growth. If he followed this ideal in his business practices, he was operating under what is essentially a textbook definition of a community bank, albeit one with a single depositor whose resources were used to the benefit of many borrowers._

On May 31, 1921, the growth and vibrancy of Greenwood screeched to a halt in the face of one of the deadliest riots in American history. The apparent spark was a young Black man in Tulsa accused of attempting to assault a young White woman on an elevator. The men of Greenwood rallied to protect the young man from being lynched.

The accusation fed an undercurrent of racial unrest as Tulsa’s White population had watched the success of Black Wall Street, even as the rise of Jim Crow segregation laws restricted where Blacks could go and what they could do. This segregation of the early 1900s was coupled with a rise in violence across the nation against Black Americans. In 1919 there were over 20 race riots against Blacks throughout the country and at least 80 Black Americans were lynched._

As tensions flared, what is known as the Tulsa Race Massacre occurred, destroying Black Wall Street. An estimated 150 to 300 individuals were killed, 1,000 Greenwood houses were burned and another 400 looted, and the entire business district was destroyed._ After the riot, the Greenwood District was rebuilt, eventually having more businesses than pre-riot Black Wall Street. However, the perception of safety and the symbolism of the original Black Wall Street was lost. The Greenwood District continued to be a thriving business district until the 1960s when integration occurred, and other social and economic factors led to its decline.

Recent Economic Trends and Disparities

Economic difficulties have continued to plague much of north Tulsa, including the Greenwood area, in recent decades. The latest U.S. Census tract-level economic data, for 2015-19, can be compared with data from a decade earlier (2005-09) to give a sense for where the area’s economy stands and how it has evolved recently. Economic comparison areas for this article will include the Greenwood area, north Tulsa, the Tulsa metropolitan area, the state of Oklahoma and the United States._

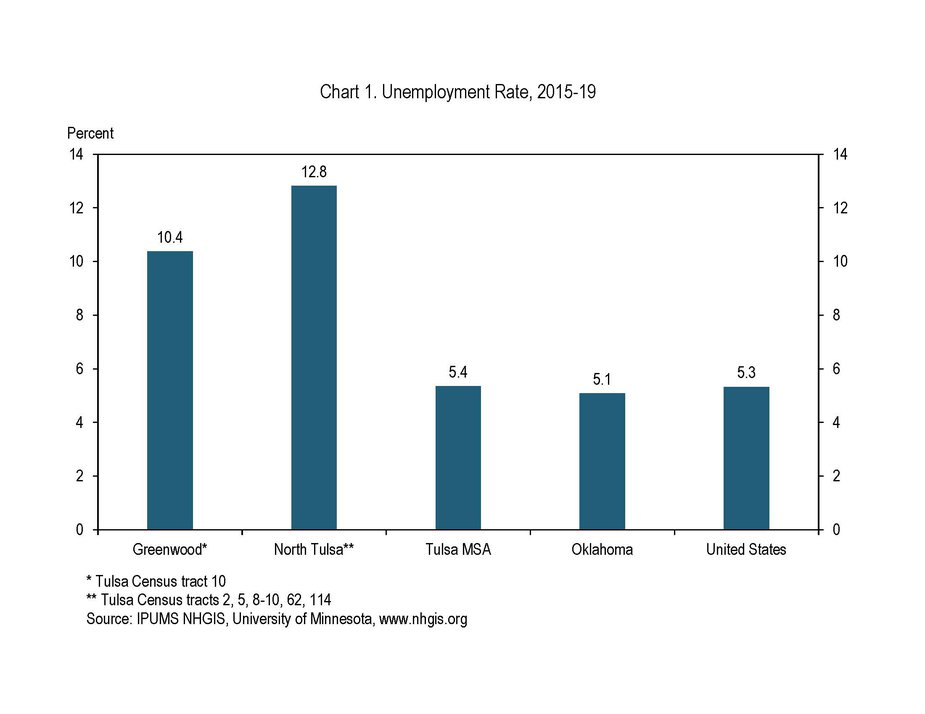

During the five years prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, unemployment in Greenwood and in broader north Tulsa—both of which are over 75% Black—was over twice as high as in greater Tulsa, the state of Oklahoma and the United States (Chart 1)._Moreover, labor force participation (the share of the potential workforce employed or actively looking for work) in Greenwood and north Tulsa remained below national, state and metro levels, masking an even higher share of people out of work than shown by the unemployment rate alone.

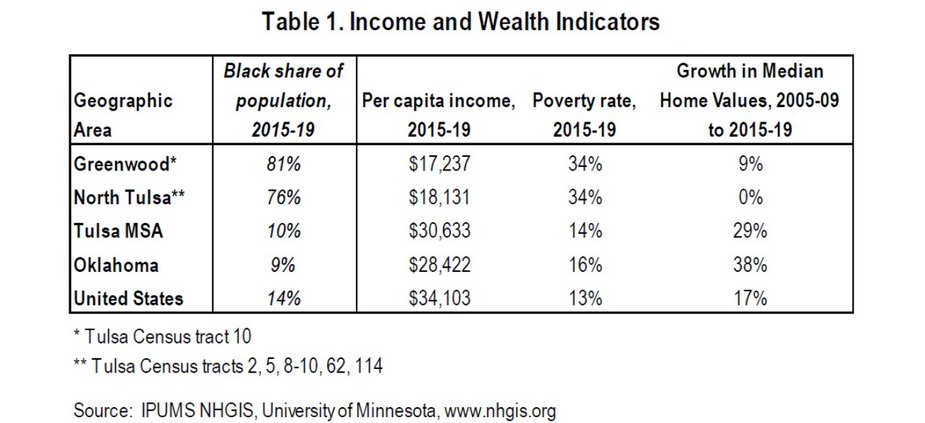

Measures of income also continued to lag considerably in the area. Real per capita personal income in Greenwood and in broader north Tulsa, at around $17,500 from 2015 to 2019, was only about half the national average, 55% of the Tulsa metro average and 60% of the Oklahoma average (Table 1). Moreover, growth in per capita income from the prior decade in north Tulsa was similar to the metro, state and nation, and income growth lagged slightly in Greenwood. As a result, these areas did not gain any ground on large pre-existing income gaps.

Similarly, the share of the population in the Greenwood census tract living below the poverty level increased somewhat from the late 2000s to the late 2010s—to 34%—while the rate largely was steady in north Tulsa overall, also at 34%. In both cases, the poverty rate remained more than twice as high as in the metro, state, or nation, which likewise showed little change over that period.

Finally, median home values in Greenwood and north Tulsa—a key source for wealth accumulation for many Americans—showed little change in the decade from 2005-09 to 2015-19. This was even as home prices in this period increased considerably in the United States, Oklahoma and the Tulsa metro area.

The Future of Black Wall Street

While the Black Wall Street of the past cannot be recreated as it was and the current economic challenges of the Greenwood area are clear, many local Tulsans are working to rekindle the entrepreneurial spirit and economic vibrancy of Black Wall Street. Three of the many organizations working to develop Black entrepreneurship in Tulsa are Black Tech Street, Tulsa Economic Development Corp. and the Black Wall Street Chamber of Commerce. Each of these organizations is focusing on a different aspect of entrepreneurship to help build the next Black Wall Street in Tulsa.

“Black Wall Street represents black people being able to build something that has never before been seen against the worst odds.” – Tyrance Billingsley, Black Tech Street

Black Tech Street is focused on creating a vibrant Black tech entrepreneurship ecosystem in Tulsa. An entrepreneurship ecosystem is the combination of local programs, policies, and relationships that support entrepreneurs in local communities. Founder Tyrance Billingsley, a descendent of Black Wall Street survivors, says that if Black Wall Street had not been destroyed, it would be the premiere Black technology and innovation hub in the nation. Black Tech Street will focus on building a large-scale collaboration of community members and organizations, corporations and other stakeholders to build a robust Black technology entrepreneurship ecosystem. The long-run objective of Black Tech Street is to transform Tulsa into a world-class inclusive innovation economy.

“Black Wall Street means that the spirit of Black business ownership is still alive and that no matter where we are, we can produce generational wealth in the same spirit that Black Wall Street did.” – Rose Washington, TEDC

The Tulsa Economic Development Corp. (TEDC) is developing a set of innovative and collaborative programs to spur Black entrepreneurship in Tulsa. TEDC is led by Rose Washington, former chair of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City’s board of directors. She says Black Wall Street shows the power and potential of revitalization through business ownership. TEDC is the lead collaborator of EDEN (Entrepreneurial Development and Education Network) in Tulsa. This network is designed to build a strong local entrepreneurial ecosystem for entrepreneurs of color. Also, TEDC is launching a franchise program targeted at Black entrepreneurs. The objective of the franchise program is to help Black entrepreneurs develop replicable franchising systems and develop multiple franchise headquarters in Tulsa. Finally, TEDC is bringing in the Mortar entrepreneurship program, which is a culturally competent entrepreneurship training program for Black entrepreneurs.

“Black Wall Street represents building our own, supporting our own, owning our own. It isn’t just having a business but supporting our businesses because that’s what they did.” – Sherry Gamble-Smith, Black Wall Street Chamber of Commerce

The Black Wall Street Chamber of Commerce, led by Sherry Gamble-Smith, is working on a variety of projects to spur Black entrepreneurship in Tulsa. Among these, the chamber is working this year on workshops, classes and resources to help Black businesses recover from the pandemic. They also are working to create stronger relationships with local banks to spur more capital and access to credit for Black entrepreneurs. One promising network created by the chamber is the formation of the Black Contractor’s Association, which has 50 Black contracting companies in Tulsa in the association. The objective of the association is to help these contractors have the right skills, resources and network of relationships to help scale.

Summary

Black Wall Street was a testament to Black entrepreneurship, community support and self-reliance. By leveraging policy, innovation, local relationships and community connectivity, Black Wall Street became a national symbol in the Black community of what can be done in the face of Jim Crow segregation, systemic racism and difficult circumstances. Economic challenges in Greenwood—home of the historic Black Wall Street—and in broader north Tulsa remain sizable today. But a number of local organizations are working to revive the spirit, structure and economic results that marked the original Black Wall Street to bring greater wealth and opportunity to the community.

Endnotes

-

1

Research assistance was provided by External LinkCourtney Shupert, Assistant Economist at the Oklahoma City Branch.

-

2

Oklahoma Historical Society. (2012, November 11). “The Tulsa Race Massacre.” Oklahoma Historical Society. External Linkhttps://www.okhistory.org/kids/printables/trm.pdf.

-

3

Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921. (2001). (rep.). “The Tulsa Race Riot” (pp. 1-178). Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921.

-

4

Ibid.

-

5

Messer, C.M., Shriver, T.E., and Adams, A.E. (2018). “The Destruction of Black Wall Street: Tulsa’s 1921 Riot and the Eradication of Accumulated Wealth.” American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 77(3-4), 789-819.

-

6

Johnson, H.B. (2014). Tulsa’s Historic Greenwood District. Arcadia Publishing.

-

7

Messer, C.M., Shriver, T.E., and Adams, A.E. (2018). “The Destruction of Black Wall Street: Tulsa’s 1921 Riot and the Eradication of Accumulated Wealth. American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 77(3-4), 789-8, pg. 792.

-

8

Todd, T. (forthcoming). A Great Moral and Social Force: A History of Black Banks. The Public Affairs Department of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City.

-

9

Johnson, H.B. (2014). Tulsa’s Historic Greenwood District. Arcadia Publishing.

-

10

Oklahoma Commission to Study the Tulsa Race Riot of 1921. (2001). (rep.). “The Tulsa Race Riot” (pp. 1-178).

-

11

The historic Greenwood area (which extends roughly from the northeast edge of downtown up to Pine Street, between MLK Jr. Boulevard and U.S. 75) coincides closely with Tulsa’s current U.S. Census Tract 10, which will be used as a proxy for the Greenwood economy. North Tulsa is defined in this article as the seven U.S. Census tracts bordered roughly by Interstate 244, U.S. 75, 36th Street and Tisdale Parkway (specifically, tracts 2, 5, 8-10, 62, and 114). All have large Black populations, with the area as a whole being 76% Black.

-

12

Data from IPUMS NHGIS, University of Minnesota, External Linkwww.nhgis.org