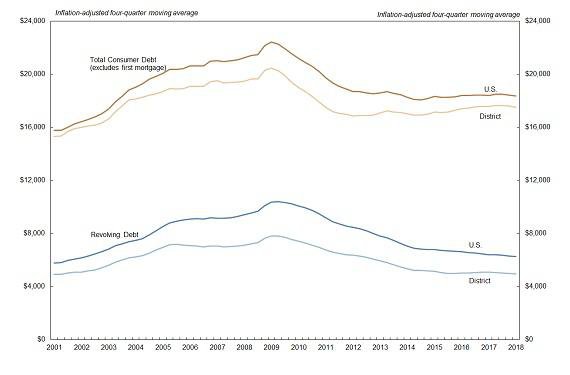

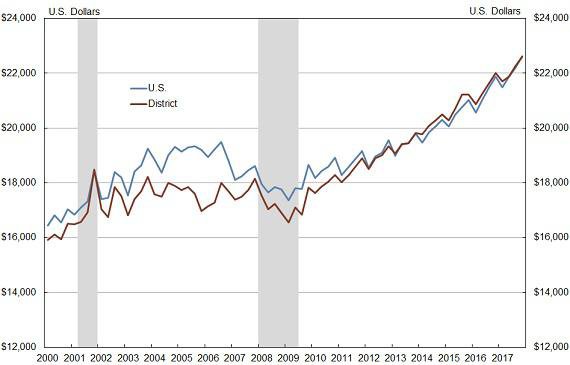

Although headlines in the last year have been about an increase in total outstanding consumer debt, average consumer debt actually has fallen in inflation-adjusted terms.1 Average consumer debt is defined for this report as all outstanding debt other than first mortgages and is presented as a four-quarter moving average, adjusted for inflation. Average consumer debt for Tenth District residents was $17,516 in the first quarter of 2018, down 0.3 percent from the first quarter of 2017 (Chart 1). Average consumer debt nationally in the first quarter was $18,354, also down 0.3 percent. Since 2012, growth in average consumer debt in the District has outpaced growth nationally. Growth in average consumer debt in the District over the last five years has been relatively modest at 2.7 percent, but has fallen nationally by 1.2 percent. Total U.S. outstanding consumer debt in the first quarter was $4.272 trillion, up 2 percent from the previous year, adjusted for inflation.2 The largest components of total consumer debt were student loans ($1.407 trillion) and auto loans ($1.229 trillion). Mortgage debt was $8.939 trillion, down 3.8 percent from its peak in 2008.

Chart 1: Outstanding Consumer Debt per Consumer and Revolving Debt per Consumer

Revolving debt has declined consistently since the Great Depression. Revolving debt is mostly credit cards, but also home equity lines of credit and retail cards. The decline in average revolving debt over the last five years has been significant: 16.4 percent in the District and 19.9 percent nationally. The divergence in all consumer debt and revolving debt implies that installment debt has been growing. The large majority of this debt is student loans and auto loans. In the District in 2017 (latest available data), the average student loan debt for those who have student loan debt increased from $23,052 to $23,424. Average auto debt increased from $19,392 to $19,565.

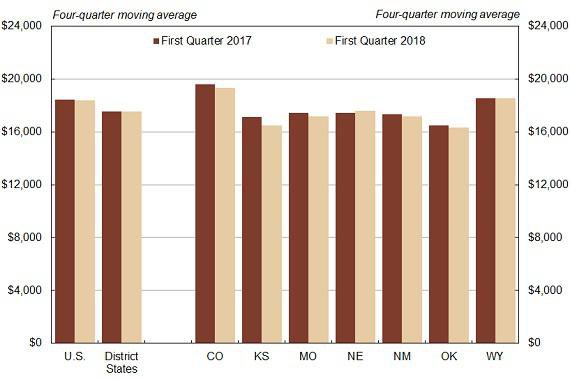

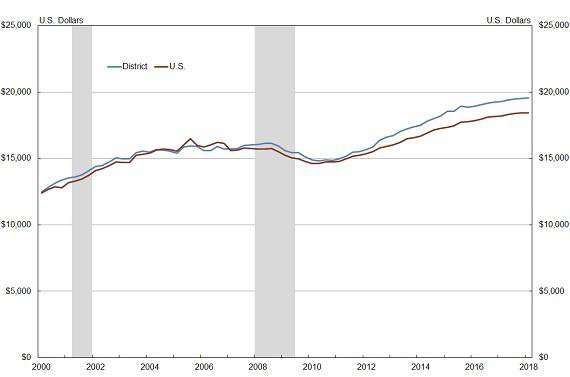

Outstanding consumer debt varies widely by District state, ranging from $16,299 in Oklahoma to $19,320 in Colorado (Chart 2). Coloradans consistently carry more debt than consumers in other District states, due largely to a higher cost of living—especially for housing—and above-average incomes. Consumer debt tends to move with both the cost of living and income. Local economic factors also play an important role in cross-state debt balances. Nebraska formerly was one of the lowest-debt states in the District, but now has average consumer debt of $17,604, highest in the District after Colorado and Wyoming.3 Moreover, consumer debt increased 1 percent over the past year in Nebraska, adjusted for inflation, compared to a 0.3 percent decline for the District as a whole. Consumer debt was flat in Wyoming but declined in other District states. Average consumer debt declined 3.8 percent in Kansas.

Chart 2: Outstanding Consumer Debt per Consumer by State

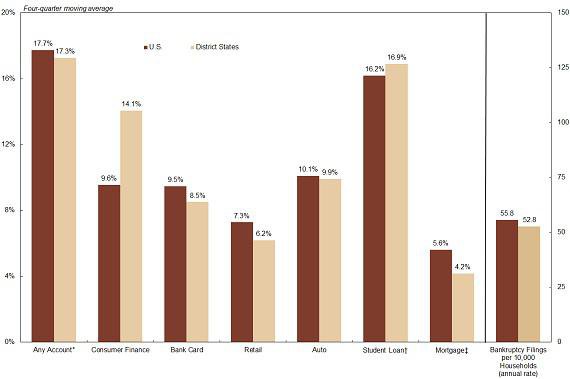

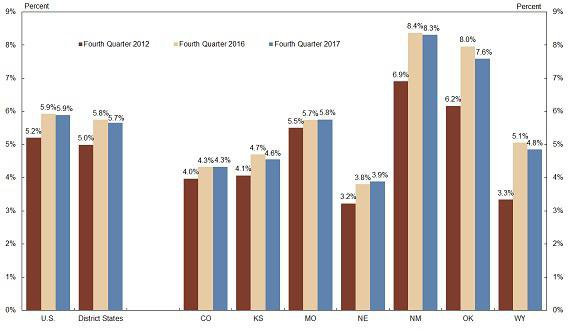

Delinquency rates are an early indication of when consumers are unable to meet the repayment requirements on their debt. Chart 3 shows average delinquency rates for the United States and District states, which are expressed as the share of consumers with accounts who have a past due account.4 Delinquency on any account ticked up 0.1 percentage point from the previous year to 17.3 percent, indicating consumers experienced little change over the past year in their levels of financial stress.

Chart 3: Consumer Credit Delinquency Rates and Bankruptcy Filings

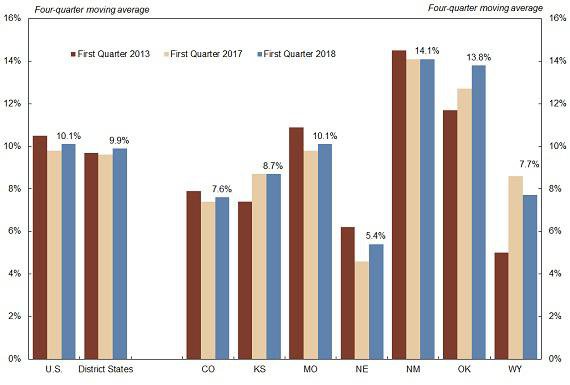

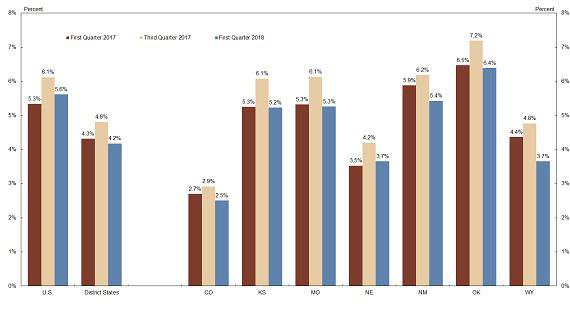

Auto delinquencies have increased in recent months. In the first quarter, 9.9 percent of District consumers with at least one auto loan were 30 or more days past due. The share of total auto debt newly delinquent in the quarter was 7.3 percent.5 The District delinquency rate is up from mid-2014 when it was at a 10-year low of 8.8 percent. The auto delinquency rate has been climbing faster in the District than in the nation. For the nation, the delinquency rate was 10.1 percent, up from 9.6 percent in mid-2014. Across the District, auto loan delinquencies generally were higher over the past year, but were mixed compared to five years ago (Chart 4).

Chart 4: Auto Delinquency Rates

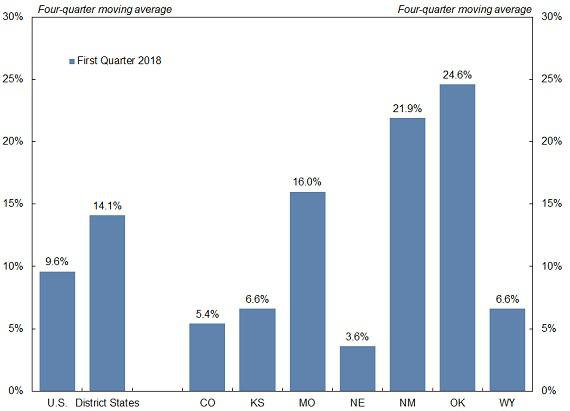

Delinquency rates on most other credit accounts are lower in the District than in the nation, but an exception is consumer finance (Chart 3). Across District states, consumer finance delinquency rates differed widely, from 3.6 percent in Nebraska to 24.6 percent in Oklahoma (Chart 5). The higher District delinquency rate is driven by significantly higher delinquency rates in Missouri, New Mexico and Oklahoma. Many factors help explain the level of debt and delinquency across states and time. The consumer finance sector is less regulated than most lending sectors, even for closed-end installment loans. State-level variation in consumer law and policy is significant and likely is an important factor.6 Consumer finance debt is a relatively small portion of total debt for most consumers, however, averaging less than $1,000.

Chart 5: Delinquency Rates for Consumer Finance Loans

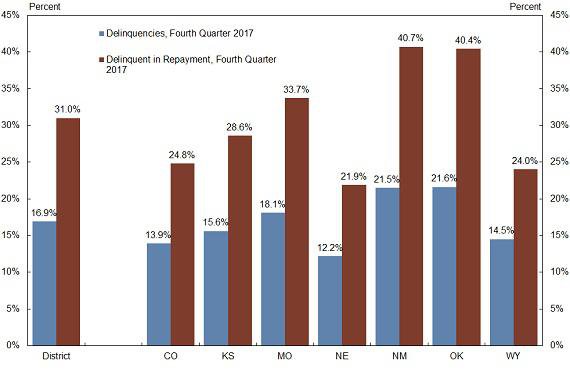

Student debt is much more likely to be delinquent than other forms of debt, especially when considering only student loans in repayment. Student loan delinquencies changed little over the past year. The District student loan delinquency rate ticked up 0.1 percentage point from the previous year to 16.9 percent. Delinquency rates fell in District states except for New Mexico and Oklahoma, where they increased moderately. Considering only student loans in repayment (ignoring loans that are deferred or forborne), student loan delinquency rates are much higher, ranging from 24 percent in Wyoming to over 40 percent in New Mexico and Oklahoma (Chart 6).

Chart 6: Student Loan Delinquencies, All Loans and Loans in Repayment

In the last issue of the Consumer Credit Report (Dec. 1, 2017), we noted that mortgage delinquency rates had jumped sharply.7 They rose again in the fourth quarter of 2017. The explanation was delinquency in recent vintage FHA loans (2012-15). We suggested that FHA borrowers, who typically have lower incomes and lower down payments, have struggled to manage larger debts associated with higher home prices. In more recent vintages, credit quality of FHA loans also has diminished with a decline of about 20 points in borrowers’ average credit score.8

Mortgage delinquency rates seem to have reversed course over the succeeding period. In March 2018, the mortgage delinquency rate (30 days or more delinquent) was down to 5.6 percent nationally and 4.2 percent in the District (Chart 7). But whether these declines are significant and represent a trend remains to be seen. Mortgage delinquencies have significant seasonality, and mortgage delinquency rates typically drop in March, after controlling for trend. Thus, the drop in delinquencies in the first quarter can be misleading. After accounting for seasonality, mortgage delinquency rates held at similar levels or were up slightly compared to a year earlier (see highlighted area of Chart 8). However, mortgage delinquency rates have been trending downward for several years. As a result, first quarter 2018 delinquencies might be expected to be lower than first quarter 2017 delinquencies (Chart 7).

Chart 7: Share of Mortgages Past Due

Overall, the average consumer in the District and the nation is in much better shape than during the Great Recession of 2007-09 and early in the recovery, and credit conditions generally are improving. However, not all measures improved in the first quarter of 2018 compared to the first quarter of 2017. Consumer debt is steady or falling in inflation-adjusted terms and revolving debt continues to decline. Delinquencies mostly are falling, although mortgage delinquency rates may be an exception. More data are needed to establish the trend. Delinquency rates on auto debt are creeping up, while delinquency rates on student loan and consumer finance debt in the last year have changed little.

Chart 8: U.S. Mortgage Delinquency Rates and Deseasonalized Delinquency Rates

In This Issue: Trends in Auto Loans

Auto sales (cars and light trucks) have increased significantly since the Great Recession. In February 2009, at the depth of the recession, new auto sales reached a trough of 9 million sales annually.9 By September 2017, sales had peaked at 18.5 million. Sales growth since has leveled off; by April 2018 sales had declined to 17 million. Largely as a result of the increase in sales, and also sales of used vehicles, total outstanding auto debt in the United States over that period increased from $766 billion to $1.229 trillion.10

Most new purchases of vehicles have some form of financing. In the fourth quarter of 2017, the latest date at which data are available, 85.1 percent of newly purchased vehicles were financed, either through a loan or a lease.11 Leases are more common for prime borrowers (33.8 percent of total financing) than for subprime borrowers (23.4 percent of total financing). Leases are included in the auto financing data in this article.

Loan terms continue to trend longer. In the fourth quarter of 2017, 75 percent of loans for new vehicles had a term longer than 60 months, as did 83.5 percent of loans for used vehicles.12 Comparatively, in the fourth quarter of 2016, 73.3 percent of new vehicle and 82.9 percent of used vehicle loans had terms longer than 60 months. The average loan term for new car loans at finance companies has increased from 60 in late 2011 to 67 in late 2017.13 The increase has been driven largely by an increasing concentration of borrowers taking out loans of 61 to 72 months maturity.14 Longer loan terms make underwater or “upside down” auto loans (car is worth less than the amount owed) more likely, which can increase the likelihood of default. Nearly one-third of borrowers are underwater on their auto loans.15

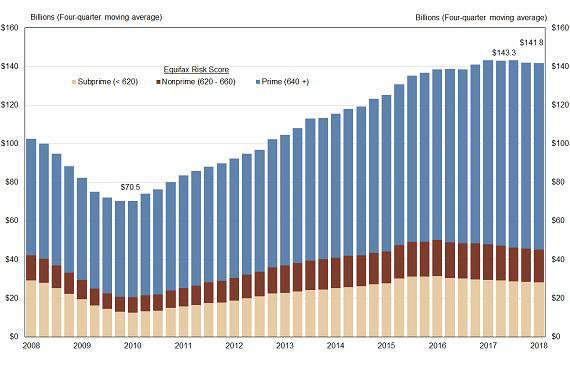

Auto loan originations have doubled since the Great Recession, rising from $70.5 billion in the fourth quarter of 2009 to a peak of $143.3 billion in the third quarter of 2017 (Chart 9).16 Originations since have leveled off, inching down to $141.8 billion in the first quarter of 2018. The subprime share of originations (credit score of 620 or lower) was 19.8 percent in the first quarter of 2018, down from 23 percent in mid-2015. The subprime share of originations plunged during the financial crisis from 30 percent in early 2005 to about 18 percent in 2010. The subprime share then trended upward to its 2015 peak before again falling off.

Chart 9: Auto Loan Originations, 2008 – 2018

Average loan amounts are rising, but at a moderate rate. The average amount borrowed for newly purchased vehicles was $22,632 nationally in the fourth quarter of 2017 (four-quarter moving average), the latest available data, compared to $19,548 five years prior (Chart 10).17 Average amount borrowed also has increased steadily in inflation-adjusted terms, rising from $20,894 (in 2017 dollars) in the fourth quarter of 2012. The annual rate of growth in inflation-adjusted loan amounts is 1.6 percent. Prior to the recession, average loan amount in the District tended to be lower than for the nation, but since has been more in line with national levels.

Chart 10: Average Loan Amount, Newly Purchased Vehicles

Auto debt has climbed consistently since the Great Recession, with District auto debt outpacing national debt significantly. Auto debt in the first quarter of 2018, which may include multiple auto loans, averaged $19,565 for the District and $18,417 nationally (Chart 11). Since reaching bottom in 2010, auto debt has grown 3.9 percent annually in the District and 3.2 percent annually in the United States.

Chart 11: Average Amount of Total Auto Debt for Consumers with Auto Debt

Delinquency rates on individual auto loans are significantly lower, suggesting it is not uncommon to be delinquent on only one of multiple auto loans. As noted above, the delinquency rate on auto debt, which may include more than one auto loan, was 9.9 percent in the District in the first quarter of 2018 and 10.1 percent in the United States. By contrast, 5.7 percent of individual auto loans were delinquent in the fourth quarter of 2017 (latest available data) in the District, and 5.9 percent of loans were delinquent nationally. Generally, auto delinquencies are lower over the past year but remain significantly higher over five years (Chart 12).18

Most auto purchases, whether new or used, are financed. Auto sales rose sharply following the recession, and along with that, auto loan originations. The average size of originations also rose sharply. Prior to the recession, almost a third of these originations were to subprime borrowers, but the subprime share has dropped significantly. The average amount borrowed on newly purchased vehicles has continued to increase since the Great Recession, as has average auto debt load (average total balance of auto debt per consumer).

Chart 12: Delinquency Rates for Individual Auto Loans

[1] See, e.g., Stacy Miller, “Burgeoning Consumer Debt Expected to Cross $4 Trillion in 2018,” The Financial Analyst, June 22, 2018; Martin Crutsinger, “US consumer borrowing up $11.6 billion in March,” The Associated Press, May 7, 2018.

[2] Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit, First Quarter 2018. This report utilizes data from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York Consumer Credit Panel / Equifax. Available at External Linkhttps://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/interactives/householdcredit/data/pdf/HHDC_2017Q4.pdf

[3] Many factors explain differences in debt loads across states, including economic conditions, income, cost of living, consumer regulations and consumer culture.

[4] For information on various ways to calculate delinquency rates and the implications of these methods, see the last issue of this report (Dec. 1, 2017). Available at https://www.kansascityfed.org/publications/community/consumer-credit-reports/articles/2017/consumer-credit-report-11-2017

[5] Federal Reserve Bank of New York, Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit, First Quarter 2018. This report utilizes data from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York Consumer Credit Panel / Equifax. Available at External Linkhttps://www.newyorkfed.org/medialibrary/interactives/householdcredit/data/pdf/HHDC_2017Q4.pdf

[6] See National Consumer Law Center, July 2015, “Installment Loans: Will States Protect Borrowers from A New Wave of Predatory Lending?” available at External Linkwww.nclc.org/images/pdf/pr-reports/report-installment-loans.pdf

[7] Available at https://www.kansascityfed.org/publications/community/consumer-credit-reports/articles/2017/consumer-credit-report-11-2017

[8] “What’s Behind the Jump in FHA Mortgage Delinquencies,” podcast, Kowledge@Wharton, Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, Feb. 23, 2017.

[9] U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, Light Weight Vehicle Sales: Autos and Light Trucks.

[10] Federal Reserve Bank of New York, First Quarter 2018.

[11] Experian, 2018, “State of the Automotive Finance Market: A Look at Loans and Leases in Q4 2017.”

[12] Experian, 2018.

[13] Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Release G.19 Consumer Credit. Average Maturity of New Car Loans at Finance Companies, Amount of Finance Weighted, Months, Monthly, Not Seasonally Adjusted. Retrieved from the Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED) database, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. Experian reported an average of 69 months for new loan terms for the fourth quarter of 2017 (Experian, 2018).

[14] Author’s assessment of data in Experian, 2018.

[15] Matt Jones, 2018, “Upside Down and Underwater on a Car Loan,” Edmunds Car Research, April 6.

[16] Federal Reserve Bank of New York, First Quarter, 2018.

[17] These and succeeding statistics are computations by the author using data from the Federal Reserve Bank of New York Consumer Credit Panel /Equifax. Balance at origination is the loan balance at open data in the credit report.

[18] Auto delinquencies, when measured as a share of total balance past due, have been increasing consistently since 2015, including in the past year. For example, 4.3 percent of balances were 90 or more days past due in the first quarter of 2018, compared to 3.8 percent in the first quarter of 2017. See Federal Reserve Bank of New York, First Quarter, 2018.