Since opening in 1920, the Oklahoma City Branch of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City has provided Oklahomans with a direct connection to the nation’s central bank. The Branch has participated in each of the Fed’s missions: financial services, regulation and supervision of financial institutions and monetary policy.

Oklahoma also played a unique role in the Fed’s creation in 1913. Oklahoma Senator Robert L. Owen was the Senate sponsor of the Federal Reserve Act of 1913. Owen brought to the job strong views on stabilizing the nation’s financial system based on his experiences operating First National Bank of Muskogee during the banking panic of 1893.

At the time, the Fed’s “decentralized” central bank structure was an innovation. The Oklahoma City Branch’s centennial provides an opportunity to explore the history of the Branch’s creation – a process that thrust both local rivalries and state pride under the spotlight.

President Woodrow Wilson signed the Federal Reserve Act on Dec. 23, 1913. However, the Act offered little direction on establishing the Federal Reserve System. For example, the Act devoted only about 300 words to the number of Districts, what those regions might look like and where to place headquarters – and fewer yet about Branches.

Oklahoma bankers strongly favored aligning with a regional Federal Reserve Bank headquartered in Kansas City. W.S. Guthrie, president of the Farmers’ National Bank of Oklahoma City, told the Reserve Bank Organizing Committee that an Oklahoma survey had found 80 percent of the state’s banks – even some near the Texas border – backed Kansas City over Dallas.

Oklahoma divided

Unexpectedly, when the Committee unveiled the 12 Federal Reserve Districts in April 1914, Oklahoma was divided. Counties north of the Canadian River were in Kansas City’s Tenth District; 34 counties south of the river were in the Dallas Fed’s Eleventh District.

In drawing the Tenth District, the Committee upended some established banking relationships. Most southern Oklahoma banks had reserve accounts with banks in Oklahoma City, or with Kansas City institutions directly. Meanwhile, few had relationships with Texas banks. However, because of the District boundaries, roughly half of Oklahoma’s banks would have to establish reserve accounts in Texas. One concern was that funds to create those accounts would be withdrawn from existing accounts, particularly in Oklahoma City.

“Bankers in the southern part of the state were … almost dumbfounded,” by the boundary lines, W.B. Harrison, secretary of the Oklahoma Bankers Association (OBA), told a reporter. Among banks in the Dallas Fed section of the state, almost all denounced the decision and promised to work to affect a change.

Within weeks, OBA members, under Harrison’s leadership, unanimously adopted a resolution that the entire state be in the Tenth District. Banks assigned to the Dallas Fed immediately appealed directly to both Federal Reserve officials and Owen’s Senate office for help. Owen also expressed his concern.

“(T)hey desire their clearings with each other … pass through an Oklahoma clearing point,” Owen wrote to the Committee secretary. “They have a natural state pride which is very powerfully felt in Oklahoma, and moreover they believe that the commercial interests of Oklahoma as a state will be much better conserved by clearing through an Oklahoma point. In this I very strongly sympathize with them, and urgently insist that the integrity of Oklahoma banking territory be not impaired by this division of the state.”

Some of the anger was largely symbolic. Structurally, nothing prevented banks from maintaining existing relationships. Jerome Thralls, manager of the Kansas City Clearing House, a key figure in establishing the Kansas City Fed and knowledgeable about the region’s banking relationships, expected that most country banks would use excess reserves in their own vaults to establish Fed accounts.

Harrison, writing to OBA members, said a divided Oklahoma would never merit a Branch. Several bankers echoed this concern to Owen and Fed officials.

After a hearing, the Fed’s Board of Governors in May 1915, moved all but eight counties in Oklahoma’s southeastern corner to the Tenth District.

Welcome to Oklahoma

While some arguments for placing all of Oklahoma in one District were valid – for example, much of south Oklahoma’s business trade was with cities to the north – others were a stretch. One was that Oklahoma, a state for just seven years, might never achieve its full economic potential if it was split between two Districts. The Oklahoma economy, however, already was flexing its muscle.

Few areas in the United States have a history as complex and diverse as Oklahoma. The region already was home to Native Americans when the Indian Removal Act of 1830 forced tribes from other U.S. regions into what was known as Indian Territory. Although tribes’ social structures and practices varied in such areas as land ownership, the area’s cotton and livestock production was substantial before the Civil War.

After the War, railroad construction, white settlement and land runs starting in 1889, caused growth in timber and coal mining in addition to agriculture. Although Oklahoma oil exploration predated the land runs, the industry boomed around the dawn of the 20th century, putting the frontier town of Tulsa on a fast track to becoming the proclaimed “Oil Capital of the World.”

Thus, while it was apparent to Oklahomans that the region eventually would merit a Branch, the location would remain undecided for some time.

Nationwide, speculation about placing Branch offices started when the 12 Districts were announced April 2, 1914. An article about the characteristics of the Tenth District in The Wall Street Journal said two Branch cities were apparent: Omaha and Denver.

The situation in the southern part of the District, however, was more vexing. The article listed Oklahoma City, Tulsa and Muskogee as contenders, as well as Wichita, Kansas.

Oklahoma City Branch employees are shown in an office picture from the 1920s. Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City archives

The Branch question

Branches were a difficult issue. While the public may have expected immediate openings of Branches, the new regional Banks were uninterested in additional offices and increased costs.

The first Branch in the Federal Reserve System opened Sept. 10, 1915, in New Orleans – a city many expected to be a headquarters—as a Branch of the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta.

Omaha and Denver both requested Branches in 1917. Omaha, a rail hub and financial center, had made a strong argument as a possible headquarters and its Branch request was approved first. The Omaha Branch opened Sept. 4, 1917. The Denver Branch opened July 14, 1918.

Requests for a Branch from the District’s southern region, largely set aside pending selection and openings in Omaha and Denver, now would get their turn.

Robert Latham Owen of Oklahoma co-authored the legislation that formed the Federal Reserve System.

The Fed Comes to Oklahoma

As The Wall Street Journal years earlier suggested, a Branch in Oklahoma was a unique challenge. There was no clear choice for a location nor one supported by all the area’s bankers. Instead, four communities laid claim to a Branch office. The competition spotlighted regional rivalries, included some intrigue and extended longer, and with more drama, than anyone preferred.

Some cities organized quickly. Tulsa bankers drafted a request within days of the announcement of the District boundaries in 1914, but didn’t even know where to send it. Muskogee bankers eventually decided to wait until the System was better established.

In 1917, when some of the Federal Reserve Act issues related to Branches were resolved, bankers from Muskogee, Oklahoma City and Tulsa joined their Denver and Omaha peers in submitting requests to the Kanas City Fed. Tulsa bankers even contacted Fed officials in Washington, D.C. Oklahoma cities received some consideration then, resulting in Muskogee being eliminated, according to a comment from Bank President Jo Zach Miller Jr. to a Muskogee reporter. The Kansas City Fed also indicated the issue would be resolved only after Omaha and Denver were open. If Kansas City Fed officials hoped time would add clarity, they were mistaken. The issue only became more complex.

In 1919, bankers in Oklahoma City and Tulsa, and Wichita, filed requests for a Branch. The Kansas City Fed’s Board set a July 24, 1919 hearing. It was not lacking for drama.

“With all the energy of auctioneers, Tulsa, Oklahoma City and Wichita ran up their bids yesterday for the favors of the district Federal Reserve Board,” according to The Kansas City Journal of July 25, 1919.

Rather than tout banking and business relationships, presenters focused on each town’s superiority. A Nebraska reporter noted Oklahoma City and Tulsa “went at it tooth and nail.”

Oklahoma City bankers said many of their peers supported a branch there and that, unlike Tulsa, their city was centrally located within the state. Tulsa bankers, meanwhile, talked about their city’s growth, its role in world oil markets and the need for the type of oil financing expertise found only in Tulsa.

Oklahoma City had a larger population and better rail access.

Tulsa had more wealth and a better relationship with Kansas City.

Wichita bankers took a third track, arguing that economic activity in Oklahoma City or Tulsa was only stopping there briefly before continuing “on the way to Wichita,” making it the appropriate choice.

After the presentations, the Bank’s Board met Sept. 25. The Board rejected one recommendation that the Board of Governors select one of the two Oklahoma cities as the Branch site, but then approved another not to open a Branch in Oklahoma at all.

An early unpublished Bank history indicates the rejection of all cities partly was a response to the self-promoting presentations, saying they “should have been based upon the commercial fitness to serve a territory not already fully served by the Bank.”

Regardless of the reasoning, the response was quick.

Oklahoma bankers launched an immediate appeal to the Board of Governors.

“We’ll have to fight for it as we have had to fight for everything else the city ever got, but we are going to win,” Daniel W. Hogan, president of the Oklahoma City Clearing House Association told The Daily Oklahoman for a Sept. 27, 1919 story. By this point, some Oklahomans felt like they repeatedly had been misled. In many newspaper accounts, Oklahomans said at least three Kansas City bankers in 1914 promised Oklahoma City would receive a Branch if the state’s bankers supported Kansas City’s headquarters bid.

While Kansas City Fed officials were mulling the issue, a story in the Kansas City and Wichita press indicated Oklahoma banks might try to bolt from the Tenth District and appeal to join the Dallas District. The story quoted Harrison – the OBA official who had led the effort to get all of Oklahoma into the Tenth District.

Harrison now was living in Wichita, was president of Union National Bank and heavily involved in Wichita’s Branch effort.

Harrison told a reporter that when he was with the OBA “the Oklahoma City bankers … had a promise from the Dallas Reserve Bank … that if they would (join) the Eleventh District, a Branch would be established in their city.”

This conflicts with letters Harrison wrote to Oklahoma bankers in 1914-15 that a Branch might not be possible unless the entire state was in the Tenth District. Harrison may not have been encouraging Oklahoma bankers to leave the Tenth District, but he added to the growing turmoil and frustration.

Those emotions were apparent in an editorial titled, “Justice for Oklahoma,” published by The Daily Oklahoman soon after the Harrison article appeared in Wichita: “Probably there has never been an act in the history of the Federal Reserve banking system so extraordinary as the act of the Tenth District Reserve Board at Kansas City in persistently and arbitrarily refusing to grant a Branch Reserve Bank in Oklahoma City.”

The lengthy editorial did not identify Harrison, but it argued that “the Dallas district would welcome Oklahoma.”

Within weeks, the Oklahoma Clearing House was coordinating efforts to redraw District boundaries – saying it was supported by about 200 Oklahoma banks.

Before that advanced, however, Oklahoma City, Tulsa and Wichita delegations went to Washington, D.C., for an Oct. 21 meeting with the Federal Reserve Board where their arguments in Kansas City continued.

After the hearings, the Federal Reserve Board on Oct. 31 asked the Kansas City Fed for details about Oklahoma banking and business relationships and said Oklahoma would receive a Branch – Wichita was deemed too close to Kansas City.

But which city in Oklahoma? The Board sent Henry Moehlenpah, who had been a Fed governor for about a week, to investigate.

Moehlenpah was a former Wisconsin banker who was “a farmer’s banker and a banker representing and understanding the needs and problems of agriculture and of the small bank.” Moehlenpah likely was best-positioned among Fed officials to understand the issues facing Oklahoma banks.

He spoke at public events in Oklahoma City, Tulsa and Muskogee, but was careful not to tip his hand, saying he would report to the Board that Oklahoma deserved a Branch. One reporter indicated the statement “was applauded to the celebrated echo.”

In addition to Moehlenpah’s work, the Board also wrote to Oklahoma banks outside of Oklahoma City and Tulsa asking which they preferred. That was good news in Oklahoma City, where bankers pointed to a previous petition in which their statewide counterparts showed strong support for Oklahoma City over Tulsa.

With the report and data in hand, the Board of Governors entered into a “long and drawn out discussion” about Oklahoma at a Dec. 17, 1919 meeting, according to the diary of Fed Gov. Charles Hamlin.

Moehlenpah reported on his trip and suggested Oklahoma City was the preferred location as long as Tulsa banks did not have to route checks that needed to move east back through Oklahoma City to the west – which would cause unnecessary delay.

Despite Moehlenpah’s report, the issue was not yet resolved.

At least two Fed governors opposed locating any Branch in Oklahoma. Hamlin, however, convinced them and moved that Oklahoma City receive the Branch with a provision that any bank in the state could send checks through Kansas City or Oklahoma City, addressing Tulsa’s concern. It was approved and announced later that day.

Serving Oklahoma in the 21st century

The Oklahoma City Branch opened Aug. 2, 1920. About 50 employees worked in offices on the second floor of the Continental Building at Second Street and Broadway. The Branch used vault space at the city’s First National Bank.

“The Oklahoma City Branch of the Federal Reserve Bank opened for business … and from the start the bank’s business was more than satisfactory. It exceeded all expectations of officials,” according to The Investor, a local business journal.

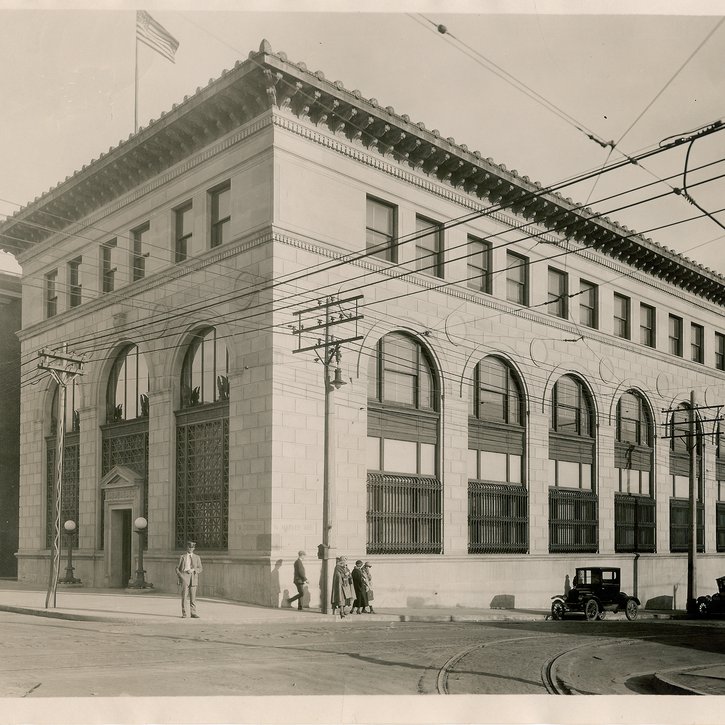

The Branch soon moved into its own building. Work on a three-story Oklahoma City Branch at Third and Harvey started in 1922. In a bit of irony, Willis J. Bailey, who as a Kansas City Fed director had led opposition to an Oklahoma Branch, had become the Bank’s president. In that position, he was responsible for laying the building’s cornerstone. The building, which The Daily Oklahoman called “a financial rock of Gibraltar,” opened in 1923. An addition to the building was completed in 1962.

Like the rest of the Federal Reserve System, the Oklahoma City Branch evolved in response to a changing financial services landscape. As Americans moved from paper-based payment methods, the Branch eliminated its check processing operations while cash operations were consolidated across the System nationwide. Those changes significantly affected the office space necessary for conducting Branch operations and the office downsized.

Today, the Branch is led by a regional economist focused on providing Fed policymakers with important insight and analysis on the Oklahoma economy and, importantly, the energy sector. Branch staff is engaged in bank supervision, community development, public engagement and economic and financial education.

Through a network of relationships with businesses and communities across the region, the Fed closely monitors banking and economic conditions, ensuring that Oklahoma’s voice is heard in the Fed’s national policy deliberations. The Branch offices are at 211 N. Robinson Ave., in downtown Oklahoma City.