While the tornado of May 25, 2016, churned up the central Kansas countryside around Chapman, Deb Wood was huddled underneath a desk with pillows packed around her in the basement of her home.

A horrible roar, the tinkling of glass and thudding noises were the sounds Wood heard as an EF4 tornado smashed the family farmstead.

When she emerged, Wood found the house reduced to rubble, her new car mangled, machinery ground up into little pieces, and concrete slabs where 10 outbuildings once stood.

She and her husband, Ken Wood, own a 2,400-acre farm that has been in the family since the 1940s.

“We had to decide whether to rebuild or walk away,” she said. “We chose to continue farming.”

Natural disasters not only destroy property, they disrupt lives. How well and how quickly individuals and businesses can recover from such devastation often depends on how financially prepared they were before a disaster.

“Savings, credit history, credit availability—all are important to your personal outcome after the financial shock of a natural disaster,” said Kelly D. Edmiston, a senior economist with the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City.

Edmiston studied the financial vulnerability and personal outcomes of individuals affected by hurricanes along the Atlantic coast from New Jersey to Texas from 2000 to 2014.

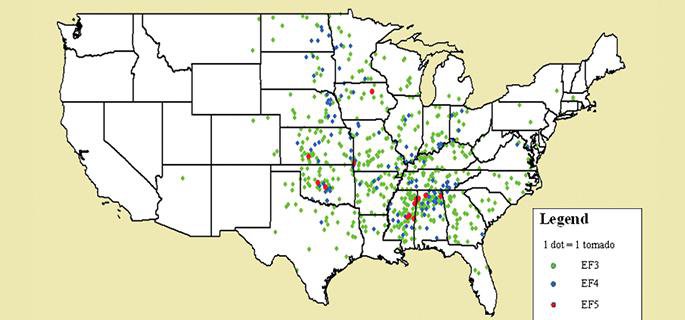

Although Edmiston studied hurricanes, tornadoes can cause the same—or even a greater degree of—destruction and disruption, he said, because they are more frequent in the region of the United States known as “tornado alley” and individuals often have less time to prepare for them.

Tornadoes cut swaths across Kansas almost every spring, and the tornado that struck the Chapman area in 2016 was a category EF4. Only an EF5—defined as winds at or greater than 200 mph—is worse in terms of wind speed, intensity and capacity for destruction. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the system that contained the Chapman tornado spawned severe thunderstorms and tornadoes over six days, causing damage adjusted for inflation estimated at $1.2 billion in Colorado, Kansas, Missouri, Montana and Texas.

Insurance covered nearly $1.8 million of the losses experienced by the Woods—not enough to replace everything. Yet, by also using their savings, they figured they could get by with less. For example, they replaced only two of their four tractors and two of their four pick-up trucks.

The Woods chose not to borrow or use credit cards to replace what they lost. They were both 58 at the time and realized they would, however, need to delay their retirement.

Edmiston found that overall, hurricanes tend to lower credit scores because individuals are not financially ready to repair, rebuild, relocate or have no income if their workplace closes or they are injured and unable to work.

Credit scores plummet because people may not have set aside money for emergenciesand they may be late paying bills. They may not have room on their credit cards for more debt and they may not qualify for a loan.

Generally, the average person has enough savings to cover 21 days of living expenses, Edmiston said. Even those considered to be the most prepared have less than 60 days’ savings.

Ken and Deb Wood were better prepared than many.

With Deb in the basement was the Wood’s financial “grab and go” box, a waterproof, fireproof box containing their passports, copies of their wills and trust, extra cash, list of financial advisers and other documents and information.

Wood, a certified financial planner, knows the importance of such a box because she teaches financial preparation as a family resource management agent for K-State Research and Extension. She works in the central Kansas district in Salina.

She now draws on her personal experience when teaching farm families and small business owners how to protect their businesses if disaster strikes.

“I want them to think about what they would do if they woke up tomorrow without anything but the clothes on their back,” she said.

Her goal is to encourage farm families and business owners to plan ahead to make recovery easier if a natural disaster occurs.

Although the Woods regularly reviewed and updated their insurance coverage, they found they didn’t have nearly enough insurance on the contents of their workshop: 40 years of equipment and tools were underinsured. Ken Wood estimates that items valued at about $100,000 were not insured.

They also re-evaluated where to keep some of their important documents.

“My husband lost all of his farm records that were stored in a big, heavy safe,” Wood said. “A fireproof safe was no match against an EF4 tornado.”

Edmiston says how communities prepare and respond can ease residents’ recovery.

“A lot of planning at the community level can make a difference in the financial outcome for individuals,” Edmiston said.

Wildfires on the march

On March 6, 2017, wildfires broke out in Kansas, Oklahoma and Colorado. The fire started in Oklahoma and spread to the ranches of southwest Kansas.

“The fire was traced to electrical lines whipping together and sparking,” said Elly Sneath, extension agriculture and natural resources agent in Meade County, Kan. “It was extremely windy, humidity was low, and the grass was dry.”

By the time the fires were extinguished a few days later, tens of thousands of livestock lay dead in fields, and thousands of miles of fence were burned up.

“It was scary and eerie in this part of the world,” Sneath recalled.

Pastures were lost as well and with them, food for the surviving cattle.

“We had to find hay and feed,” said Loren Sizelove, an extension educator in Beaver County in the Oklahoma panhandle.

Word quickly spread by social media and within days, donations of hay were being trucked in from all over the country.

To coordinate the convoys of hay and fencing supplies, Sneath said she left her office March 10 and didn’t return for a full day until April 28.

Much of her time was spent on the phone giving directions to drop-off points and helping truckers locate remote areas of the county: “ ‘Just give me an address’ doesn’t work out here,” Sneath said.

In Beaver County, Sizelove creditsmembers of 4-H clubs—some from as far away as Michigan—with saving calves orphaned by the fires: “Several loads of powdered milk were donated, and 4-H kids helped bottle-feed the calves.”

Insurance, for the most part, did not cover fences. Livestock fencing costs between $8,500 and $10,000 a mile.

“It’s a separate policy that many people will have now,” he said.

The cost of fence insurance needn’t be prohibitive, Sizelove said. Some policies allow a rancher to insure a certain number of miles of fence, rather than a designated area.

Like Deb Wood, Sizelove teaches residents in his county how to prepare for and minimize the damage from natural disasters.

“We do programs now about wildfire,” he said. “Landscaping around a house, for example, can reduce the risk of fire. If a tree is too close to a house, maybe it should be removed.”

By all accounts, losses were reduced by the relief efforts of neighbors, local officials and assistance from hay producers nearby and throughout the country.

Getting back to normal

Edmiston’s research found that the impulse of those who experience a natural disaster is to try to get back to “normal,” to the way life was before the tornado, fire, flood or hurricane.

“There’s a geographic attachment,” he said. “They want to rebuild where they live.”

The Woods, for example, rebuilt their house on their property but in a different location.

Carol Taylor’s family also chose to rebuild and remain where they were when a tornado in May 2003 destroyed much of their home in Gladstone, Mo., a suburb of Kansas City. In that storm event, about 400 tornadoes were reported over a week in the Midwest, the Mississippi, Ohio and Tennessee valleys, and parts of the Southeast. Inflation-adjusted damages were $5.6 billion, according to the NOAA.

Taylor still lives in that house, but nearly everything else about her pre-tornado life has changed.

“If the tornado hadn’t struck, there is absolutely no way I would be where I am today,” Taylor said. “I never wanted to be a business owner.”

Taylor owns A Clean Slate, a Kansas City-based commercial and construction cleaning company that employs 30 people.

It began when a builder offered to pay Taylor to clean her own house before the family moved back in after repairs were made. Until she gave the builder an invoice, Taylor said she never thought about going into business for herself.

Knowing that other tornado-damaged homes soon would need cleaning, Taylor drove around the neighborhood, leaving homemade business cards with contractors. She used her savings to start a residential cleaning service.

In 2006, her business changed direction when she was awarded a contract to clean a million square feet of space.

Construction companies, parking garages and wastewater treatment plants are now among her clients. Taylor said she recently hired a human resources manager and opened an office in Denver.

“None of this would have happened if the tornado hadn’t struck our house,” Taylor said.

Disasters can be viewed as an opportunity to make some changes, said Elizabeth Kiss, associate professor of family studies and human services at Kansas State University in Manhattan.

“Getting back to the way it was” may not be the best option.

Plan, Prepare, Prevail

Kiss oversees the“Prepare Kansas” online challenge during National Preparedness Month in September. The state campaign was started in 2013 to encourage Kansans to be financially prepared for disasters and emergencies.

“We want people to be informed ahead of time rather than reacting to a disaster,” Kiss explained.

Taking a household inventory, reviewing insurance coverage, having an emergency fund to cover deductibles are some of the recommendations. Financial preparation ahead of time and a willingness to consider other options after a disaster may mean the difference between feeling victimized and feeling empowered.

“Natural hazards of whatever type generally do not need to be as disastrous as they are,” Edmiston said.

Don’t wait: Take steps now

To find out more about how individuals and businesses can prepare for disaster, the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City has developed “Plan. Prepare. Prevail. A Disaster Financial Readiness & Recovery Blueprint.”

For further resources, read “External LinkFinancial Vulnerability and Personal Finance Outcomes of Natural Disasters” by Kelly D. Edmiston.