Since its opening in 1917, the Omaha Branch of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City has given Nebraskans a local connection to the nation’s central bank through its participation in each of the Fed’s mission areas, including financial services, the regulation and supervision of financial institutions, and monetary policy.

In addition to providing Fed policymakers with important insight and analysis on Nebraska’s economy, the Branch continues to meet the demands of businesses and consumers who rely on the Federal Reserve every day.

The Omaha Branch is entering the next 100 years with plans for growth. With a strong focus on technology, the multiyear plan will include physical improvements to the current building and grounds, which are already under way, and will add approximately 100 new positions at the Branch.

As supporters said 100 years ago, Omaha has always been an important banking town, so the city’s connection to the nation’s central bank seemed destined, although establishing that connection took some time.

The road to the Federal Reserve

The United States tried to establish a central bank on two occasions, once in 1791 and again in 1816; however, both banks lasted only a few years due to great political opposition and concerns that the central bank did not represent the needs and interests of all Americans. After several bank panics and cyclical economic turmoil from the mid 1800s to the turn of the 20th century, lawmakers realized a U.S. central bank was an essential part of establishing and maintaining the country’s economic stability.

While other countries had successful central banks that operated under tightly consolidated authority, those models would not work in the United States. Americans were more distrustful of federal authority than many of their European counterparts. Additionally, the broad and diverse U.S. economy presented a potentially wider range of economic and financial challenges than might occur in a smaller nation.

Recognizing the uniquely American demand for a system with checks and balances, congressional leaders, including Oklahoma Sen. Robert L. Owen, designed a new compromise structure. It would be a network of regional banks, each operating under the leadership of local boards of directors, with oversight by a central government agency. It was a unique combination—a “decentralized” central bank that blends both public and private control in a reflection of the nation’s checks and balances system.

President Woodrow Wilson signed the Federal Reserve Act on Dec. 23, 1913, creating the Federal Reserve System. The legislation designated a central bank comprising a unique network of banks serving local regions, or Federal Reserve Districts, with national coordination by a Board of Governors in Washington, D.C.

The task ahead

The system presented the nation’s communities a unique opportunity to play an important role, and many were eager to participate. Among those praising the Federal Reserve’s design was the Lincoln (Neb.) Trade Review, which described the nation’s pre-Fed banking structure as giving all the country, equal representation.

While the concept may have found supporters, when it came to the details of establishing the Federal Reserve System’s regional map, the legislation offered relatively little direction.

A Reserve Bank Organizing Committee was formed consisting of a two-member panel—Agriculture Secretary David F. Houston and Treasury Secretary William G. McAdoo—that would create the Districts and designate “Federal Reserve cities” where the regional banks would be located.

The Committee’s first formal session was held at the Treasury. The pressure to complete the task quickly only compounded the already difficult question of how to divide the country.

The task ahead

Although the number of Reserve Districts was hotly debated prior to the Act’s approval, the issue was among the first, and perhaps the easiest, for the committee to resolve.

It “became obvious that if we created fewer banks than the maximum fixed by law, the Reserve Board would have no peace till that number was reached,” Houston wrote.

Ballots were sent to 7,741 national banks that had formally assented to the provisions of the Federal Reserve Act asking each their preferences for Reserve Bank cities. The vote, however, was only one component in determining the Reserve Bank locations and the Federal Reserve Districts. The committee appointed a Preliminary Committee on Organization, headed by Henry Parker Willis, who served as a financial expert on the House’s Ways and Means and Banking and Currency committees, to address several issues related to the organization of the Federal Reserve, including the drawing of some preliminary District maps. Willis later served as the first secretary of the Federal Reserve Board.

Meanwhile, the committee embarked on a tour of the United States under a travel schedule that was aggressive even by modern standards. During a five-week span, Houston and McAdoo logged 10,000 miles, convened hearings in 18 communities and heard presentations from 37 cities.

Welcome to Nebraska

Agriculture has always been the fuel for the Nebraska economic engine. And in the early 1900s, that engine was firing on all cylinders. Nebraska was fourth in terms of agricultural wealth, behind only Texas, Iowa and Illinois, according to the 1910 census, with nearly 130,000 farms covering nearly 80 percent of the state’s total land. In 1912, total farm production, including crops and livestock, topped $428 million, up 7 percent from the previous year.1

Transportation was another important component in the Nebraska economy, with the Omaha area’s involvement dating back to the founding of the Union Pacific Railroad in the 1860s. By 1914, the Union Pacific Line took 880,000 tons of freight into its terminals in Omaha, South Omaha and neighboring Council Bluffs, Iowa. Overall, railroads, including Union Pacific, Chicago, Burlington & Quincy, and others, did more than $14.6 million in business in Nebraska the year the Federal Reserve Act was enacted.2

In terms of banking, at the time of the Federal Reserve Act’s approval, Nebraska was home to nearly 1,000 banks, most of them small, community institutions. The state’s 721 state-chartered banks had a total capital and surplus of $17.8 million. Comparatively, 245 Nebraska banks with national charters had total capital and surplus of $24.6 million.3

Regional rivalries for regional Reserve Banks were evident in many areas of the country and, as might be expected, emerged in Nebraska, where those living in both Omaha and Lincoln believed that they should host one of the locations. Each city presented its argument for a Reserve Bank to the Organizing Committee during a daylong hearing in the Federal Court Room of what was known then as the Post Office Building in Lincoln on Jan. 24, 1914. The structure at 129 N. 10th St. was later known as the Old Federal Building and redeveloped into the Grand Manse.

P.L. Hall, president of Lincoln’s Central National Bank, presented the Lincoln Clearing House’s proposal for a massive Federal Reserve District that would be served by Lincoln. The District spanned from the western half of Iowa to parts of Oregon and Washington in Pacific Northwest, with sections of Kansas and Missouri to the south and a third of Montana to the north.

Besides Lincoln’s business and banking connections, supporters were also relying on the political clout of its most famous resident: Secretary of State William Jennings Bryan, who had called Lincoln home since 1887. Bryan rose as a political force on the national stage due largely to his own views on the issue of national currency. The Democratic Party nominated Bryan to the presidency three times—none of which he won. In the 1912 presidential election, he played a critical role in securing Woodrow Wilson as the Democratic nominee. After winning the presidency, Wilson named Bryan his Secretary of State.

The Omaha proposal appeared to be based in part on the idea that Kansas City was likely to receive a Reserve Bank with Omaha serving a distinct territory of its own. Omaha’s supporters made a case to the committee that their city was far more closely aligned with Chicago than Kansas City, despite the closer proximity of its southern neighbor.

For example, Ward Burgess, a dry goods wholesaler from Omaha was asked about business relationships, he noted that people in Kansas City “are very friendly in a social way, but when it comes to trade relations we do not want in any District which Kansas City would serve.”4

Later, Henry W. Yates, president of the Nebraska National Bank of Omaha made certain to cast his city in a favorable light against its potential rival to the south.

“…Omaha has always been a banking town,” Yates said. “... (The) banking business came as naturally to Omaha as water comes down hill. We were the banking center of the whole Western country when Kansas City had comparatively little banking capital.”5

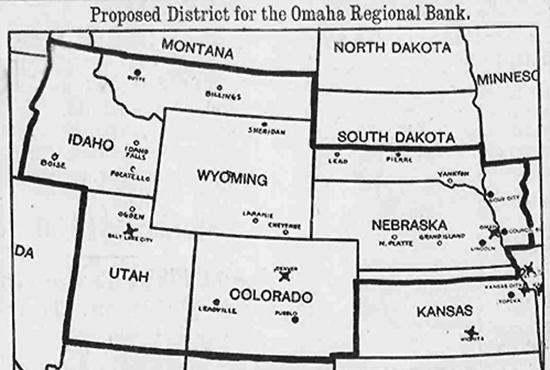

Omaha’s supporters suggested a Reserve District encompassing western Iowa; southern South Dakota; a northern tier of Kansas, stopping short of Kansas City; parts of Montana and Idaho, as well as all of Nebraska, Wyoming, Colorado and Utah.

The selection

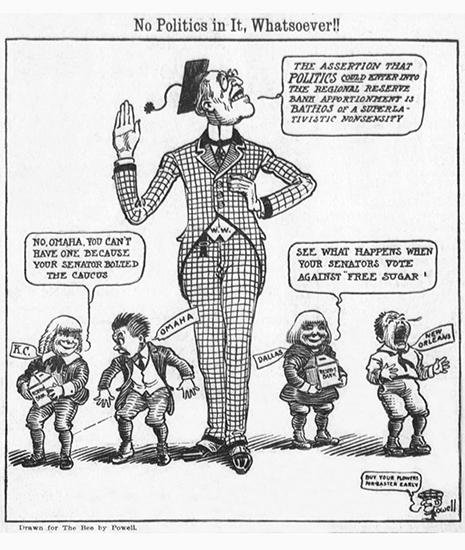

Despite supporters’ best efforts, the Reserve Bank Organizing Committee decided to include Nebraska within the Tenth Federal Reserve District with the headquarters in Kansas City, which did not sit well with Nebraskans. Omaha supporters were outraged by the decision, which they believed to be heavily influenced by politics.

Nebraska Sen. Gilbert Hitchcock quit the Democratic Caucus the previous July amid a dispute related to his proposal to institute a progressive excise tax on tobacco firms.6

“The rejection of Omaha’s superior claims as a banking center was apparently foreordained when our United States senator got in bad with the administration by bolting his party caucus and exposing himself to discipline,” The Omaha Daily Bee wrote in an editorial titled “Just Politics—That’s All.”7

Omaha banker Yates, meanwhile, pointed a finger directly at Bryan.

“It is disgraceful—it is outrageous,” Yates told a reporter. “In my judgment, the outcome will have decided political effect. I can’t see any other result but that Mr. Bryan has killed himself in Nebraska. There is no question that but Lincoln was raised up as a candidate for a place to be knocked down, carrying Omaha with it.”

Within a matter of days, the city’s Clearing House Association passed a resolution asking for Nebraska and Wyoming to be transferred to the Chicago Fed District. A petition seeking to redraw the District lines in that manner was filed with the Fed’s Board of Governors. The request was rejected.

Lincoln’s supporters, meanwhile, moved on a different track, sending a congratulatory telegram to the Kansas City Clearing House and reminding the organization that Lincoln would like to be considered for a branch office when those decisions were made.

Meanwhile, new rivals for branches were emerging, with bankers in Oklahoma City, Tulsa and Muskogee, Okla., as well as those in Wichita, Kan., all reaching out to Kansas City to express their interest. Kansas City bankers, meanwhile, predicted that the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, once operational, would move quickly to open branch offices in Omaha and Denver.

The Fed comes to Nebraska

The issue of branches raised a somewhat difficult question for the nation’s new central bank. Some of the public expected to see branch locations opening almost immediately after the Federal Reserve System became operational. The new regional banks, however, were uninterested in opening additional offices, and taking on increased costs, without a clear demonstration that the Branches were necessary to serve their Districts.

The Federal Reserve Act offered little guidance. Although the Act does spell out some provisions for branch governance, it offers no criteria or requirements for opening Branch offices.

According to an unpublished history of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City authored by early Bank employee Jess Worley, the Omaha Clearing House banks sent a letter to the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City officially seeking a branch in June 1917.

Jo Zach Miller, bank president, and Charles Sawyer, chairman of the bank’s board of directors, traveled to Omaha on July 10 to explore the issue.8 The pair arrived in Omaha in time for dinner and met with bankers for two hours before returning to Kansas City by train that evening. Despite the hopes of some, Miller did not use the July 10 meeting to announce the formation of an Omaha Branch. The city’s bankers, however, left the meeting encouraged.

“I feel that our meeting was a success, and although nothing was definitely determined, I think several questions which have been bothering us are satisfactorily settled,” Luther Drake, president of the Merchants National Bank, told The Omaha World-Herald for its July 11, 1917, edition.

The Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City’s board approved the Omaha Branch during a meeting two days later. The Federal Reserve Board in Washington, D.C., signed off on the Kansas City decision on July 18.

The branch’s first board of directors included Drake, Hall, who had spoken to the Reserve Bank Organizing Committee on Lincoln’s behalf during the hearing; J.C. McNish from McNish Cattle Loan Co. in Omaha; W.B. Hughes from the Omaha Clearing House; and R.O. Marnell, a banker from Nebraska City.9

The branch opened on Sept. 4, 1917, in what was then known as the old First National Bank Building at 1219 Farnam St. The Federal Reserve later purchased the building, which became known as the Farnam Building, for $165,000 in 1920. The branch, however, soon needed new space and began construction on a new building at 1701 Dodge Street, which opened in November 1925. The building, which stood on the site that has since become home to the U.S. District Court, included what was called a “round house” with an 18-foot round moving platform that armored trucks would pull onto and then be rotated for currency and coin delivery.10

That delivery area may have been its most active in August 1931 amid a run on Nebraska banks caused by the closing of four institutions over the span of a week. The Federal Reserve sent an additional $3 million in currency from Kansas City to the Omaha Branch to meet possible withdrawal demands. The city’s leading banks, meanwhile, announced they would extend hours to accommodate those seeking to withdraw funds.

“With the announcement that the larger banks were prepared to meet the emergency with plenty of cash on hand, the crowds milling about the entrances thinned a little and the tension seemed broken,” read an Associated Press report.11

The Omaha Branch expanded its headquarters, including its vault space, with a two-story addition in the mid-1950s. The Bank considered future branch expansion with nearby property purchased in the 1960s and 1970s that would have provided room for further additions. Rather than expand, however, the Federal Reserve purchased property at 22nd and Farnam Streets in 1981 and, in 1984, began construction on the current Omaha Branch office. The facility opened in 1986.

Less apparent from the outside have been the evolution in branch operations reflecting developments in the financial system and the economy. Initially, the branch served banks in both Nebraska and Wyoming. Wyoming banks were transferred to the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City’s Denver Branch in 1971. Operationally, as consumers moved away from the use of written paper checks to electronic payments, the Federal Reserve reduced its check processing capabilities across the Federal Reserve System. The Omaha Branch processed its last check on April 23, 2004. The Omaha Branch’s Cash operation consolidated to Kansas City with the opening of the new headquarters in 2008.

While the consolidations resulted in a decrease in staff, the Branch’s engagement in the region continued to expand, and plans for future growth, especially concentrating in technology, are currently under way.

Endnotes

1 All of this data was submitted by various Nebraska interests and is included in U.S. Reserve Bank Organization Committee Exhibits and letters submitted.

2 All of this data was submitted by various Nebraska interests and is based on annual reports and other documents produced by the various rail lines and filed with the Nebraska State Railway Commission. It is included in U.S. Reserve Bank Organization Committee Exhibits and letters submitted.

3 Location of Reserve Districts in the United States, letter from the Reserve Bank Organization Committee, April 29, 1914.

4 Reserve Bank Organizing Committee hearing at Lincoln, Neb. Jan. 24, 1914, Stenographer’s Minutes.

5 Reserve Bank Organizing Committee hearing at Lincoln, Neb. Jan. 24, 1914, Stenographer’s Minutes.

6 Unlike modern day tobacco taxes, Hitchcock’s measure had no connection to health-related concerns and was instead proposed as a measure against the dominance of “big tobacco” producers over their smaller competitors. The tax was designed to curtail the production of only a handful of the nation’s 2,700 tobacco companies and 20,000 cigar manufacturers by making production unprofitable above certain specified levels. For details, see New York Times, June 6, 1913. Pg. 1. Tobacco Tax Aimed at a Few Big Firms.

7 Omaha Daily Bee, April 4, 1914.

8 Miller’s title at the time was actually “governor.” The title of the position was later changed to president. President is used to provide clarity.

9 Press Statement from the Federal Reserve Board, issued July 18, 1917.

10 Kitt Chappell, Sally A. Architecture and Planning of Graham, Anerson, Probst and White, 1912-1936. University of Chicago Press. Chicago,. Ill. 1992.

11 Lincoln Star, Aug. 15, 1931.

Further Resources

Read “Confidence Restored: The History of the Tenth District’s Federal Reserve Bank” by Tim Todd.

Comments/questions are welcome and should be sent to teneditors@kc.frb.org.