Most economists say the economy is getting stronger.

Overall, employment reports this year show a labor market that is near full employment—the unemployment rate dipped below 5 percent, the labor force participation rate reached pre-recession levels and the employment-population ratio almost reached 60 percent—indicating the United States has gotten back to work since the Great Recession.

Although domestic manufacturing has decreased, consumer confidence has remained steady and even the gap between imports and exports closed in August.

Entrepreneurship, as measured by new business creation, however, has declined steadily for the last decade. During the financial crisis, creation of new businesses dropped 30 percent. And data from the Brookings Institution shows business formation dropped 8 percent from 1978 to 2011 as business closures outpaced business formation.

At the end of 2013, U.S. Census Bureau data showed firms 16 years or older made up almost 40 percent of all businesses; meanwhile, firms 1 to 5 years old declined to less than 10 percent of all businesses.

This decline is significant because labor statistics show newer businesses account for most of the new job creation in the United States while older businesses lay off as many employees annually as they add.

There is a ray of hope for entrepreneurship in America. Some analysts say the millennial generation, which has become the largest segment of the prime-age workforce (ages 25-55), is more inclined to embrace the entrepreneurial spirit than the corporate world. There’s also an increase in minority-owned business, especially women, who are the fastest growing group of entrepreneurs in the United States.

Creating a new business

Daveyeon Ross displayed the spirit of an entrepreneur at an early age, growing up on the Caribbean island nation of Trinidad and Tobago. One time Ross gave his mother more than $1,000 in the local currency (about $200 U.S.) to use during a trip to New York City to buy sports-related hats.

“I was going to school with a bag of hats every day and selling them for almost a 1,000 percent profit,” he said.

That same spirit led to a basketball scholarship in the United States, where he earned a bachelor’s degree in computer science at Benedictine College in Atchison, Kan., and a master’s in business from MidAmerica Nazarene University in Olathe, Kan.

After college he went to work at Sprint, where he led his own technology team.

“I’m very appreciative of them,” he said of Sprint, “but it was such a large organization; I couldn’t initiate change.”

Much of the innovation in any large corporate environment, he explained, isn’t innovation, per se. He called it “intrapreneurship,” where a company improves upon what it already has created, but doesn’t create anything new.

“Entrepreneurship allows me to control my own destiny,” he said. “It allows me to create something new, to innovate and take credit for my own work, and I’m not being told what I can and can’t do.”

After leaving Sprint, Ross founded Digital Sports Ventures, an interactive technology company with rights to NCAA Division I college sports video across seven major conferences. The company grew, and he sold it in 2011 to a large ad network.

Like most entrepreneurial endeavors, Ross’ next business venture started with a question. In his case, the question revolved around how to capture data about player performance in basketball. And while Ross knew the answer would be complex, he believed that with his background in basketball and his technical skill he could form a team to find the answer.

Ross co-founded ShotTracker with Bruce Ianni in summer 2013. Ianni had created Innovadex, an online search engine—a “Google for chemists”—which he sold in 2012.

Their original ShotTracker focused on using hardware and software to capture shot attempts, makes and misses for a single basketball player. After finding some success with the product, the co-founders and their development team created ShotTracker Team, which simultaneously captures the stats of every player on the court in real time.

“The team product involves a whole different level of technology,” Ross said.

The hardware includes lightweight sensors that are attached to the players’ shoes, installed in the basketball—the company has an agreement with sports manufacturer Spalding—and above the court. Data are transmitted to a software program, which gives coaches and players instant performance data.

The business continues to refine the program and is working with a company to install sensors in the floor of portable basketball courts.

With its success, ShotTracker has created new full-time and part-time jobs and has moved into a new office in Merriam, Kan.

“We haven’t reached all our goals,“ Ross said. “We sometimes create new goals as we go along, but we’re not where we want to be yet.”

With this drive to succeed, Ross says ShotTracker can grow into a large company, or eventually merge with a large corporation.

“That’s the irony of becoming successful,” he said. “You can take that entrepreneurial spirit and turn it into a corporate one.”

Finding new solutions

Shifts in U.S. population from urban cities to suburban environments began shortly after World War II and occurred for reasons such as congestion, cheaper housing and other economic and social factors. As suburbs began to develop, there also was a philosophical shift among businesses, where companies sought open areas to develop business parks with modern buildings and more space for parking. The change often resulted in the loss of jobs in urban areas.

Dell Gines, a senior community development advisor with the Kansas City Fed, says this shift helped create a strategy of economic development based on “attraction,” where communities or regions recruit large companies or plants to spur economic development.

To entice companies, cities at first offered incentives to reduce a company’s operating and capital costs such as tax and utilities abatements, low cost property leases and bond revenue for construction. The justification for this strategy, Gines said, is that the long-term economic

gain the relocating company provides will be greater than the cost of the incentives the company receives.

Although this practice has become common, it does have problems. Research in 2004 found that states spend billions annually on economic development incentives with limited evidence that, on-net, they are effectively creating economic growth, Gines said.

For many communities, particularly smaller towns, researchers have characterized attraction-based development as both risky and costly. Research from Kansas City Fed Economist Kelly Edmiston suggests an alternative strategy of focusing on the growth of existing small businesses may be a more cost-productive strategy of economic development and job creation than recruitment of new businesses.

Gines contends that entrepreneurship can create economic solutions where traditional tools have come up short, especially in urban communities.

“Small businesses are called the backbone of the U.S. economy because they create jobs, wealth and a local sense of place and community,” he said.

Entrepreneurship-based strategies, which Gines calls “grow your own” strategies, focus on supporting the development and growth of local entrepreneurs and small businesses to create sustainable and balanced economic growth at the local level.

For example, the Crossroads Arts District was once a neighborhood in disrepair in the heart of Kansas City, Mo. It’s now an enclave of small businesses, including one-of-a-kind restaurants, small tech startups, boutique shops, restaurants and other creative businesses. Instead of the city attracting large companies to boost the community’s commerce and create jobs, it fostered a locally-grown economic system that encouraged entrepreneurship and the development of small businesses that created jobs, tax revenue and provided a place where people desire to live, work and play.

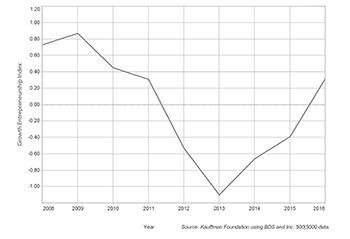

Kauffman index of growth entrepreneurship (2008-2016)

The future

The Kauffman Index of Growth Entrepreneurship indicates entrepreneurial business growth has increased out of negative numbers for the first time since the recession. Although there was a sharp increase in business startups ahead of the recession, mostly due to people trying to find alternative work, startup activity declined sharply in the recovery. Since 2014, however, the number of startups has increased steadily, with ownership of small businesses expected to reach pre-recession levels by 2017.

This trend is supported by a 2014 survey by Bentley University that suggests millennials take a different view of career success, with many of them seeking more independent and entrepreneurial business opportunities than past generations.

According to the survey, only 13 percent of respondents had career goals that involve climbing the corporate ladder while almost two-thirds, or 67 percent, said their goals involve starting their own business.

Those findings are backed by a 2016 BNP Paribas Global Entrepreneurialism Report that surveyed 2,600 high and “ultra-high” net worth entrepreneurs ages 20 to 35 from 18 countries.

The report finds millennials discovered entrepreneurship earlier than baby boomers. Boomers started their own business at age 35, while millennials started their first business at 27. And the generation is still young, analysts say, with the percentage of startups expected to increase during the next decade.

According to a recent U.S. business owner survey, the fastest growing group of entrepreneurs in America is minority women. From 2002 to 2012, Black female entrepreneurship grew by 178 percent, Hispanic by 172 percent and Asian by 121 percent.

“This potentially is a good sign due to the changing demographics in America,” Gines said.

Further Resources

Read "Grow Your Own" e-book by Dell Gines.

Read “The Role of Small and Large Businesses in Economic Development” by Kelly Edmiston