I. Economic Update for LMI Communities

The first section of the LMI Economic Conditions Report provides an assessment of economic conditions in low- and moderate-income (LMI) communities in the Tenth District, which is composed of Colorado, Kansas, the western third of Missouri, Nebraska, the northern half of New Mexico, Oklahoma and Wyoming. Section II focuses on special topics. A person, household, or community is LMI if income is below 80 percent of area median income. For urban areas, area median income is metropolitan median income. For nonmetro areas, area median income is state median income.

Section I-A examines general perceptions of economic conditions in LMI communities and the demand for services from community organizations. Section I-B focuses on labor market conditions and job availability. Sections 1-C and 1-D focus on affordable housing and access to credit, respectively.

I-A. General Assessment

Most indicators of economic and financial conditions in LMI communities rose moderately in the fourth quarter of 2017. The LMI Affordability Index and LMI Credit Access Index increased significantly, largely reversing declines from the second quarter of 2017 (all references to an index are current conditions relative to the previous quarter unless stated otherwise). Values for all indexes are in Table 1.

Diffusion Indexes

Survey participants respond to each survey question by indicating whether conditions during the current quarter were higher (better) than, lower (worse) than or about the same as in the previous quarter or year. An index showing conditions relative to the previous quarter is a “quarter index,” while an index comparing conditions to one year ago is a “year index.” Providers also are asked what they expect conditions to be in the next quarter (“expectation index”). Diffusion indexes are computed by subtracting the percentage of survey participants that responded lower (worse) from the percentage that responded higher (better) and adding 100. The exception is the LMI Services Needs Index, which is computed by subtracting the percentage of survey participants that responded higher from the percentage that responded lower and adding 100 so that higher needs translate into lower numbers for the index. A reading below 100 indicates the overall assessment of respondents is that conditions are worsening. For example, an increase in the index from 70 to 85 would indicate conditions are still deteriorating, by consensus, but that fewer respondents are reporting worsening conditions. Any value above 100 indicates improving conditions, even if the index has fallen from the previous quarter or year. A value of 100 is neutral.

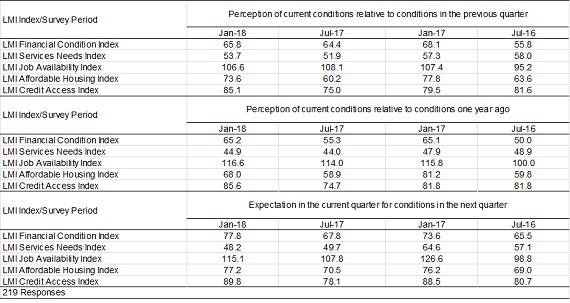

Table 1: Diffusion Indexes For Low- and Moderate-Income Survey Responses

Notes: The diffusion indexes (see Box), were computed from responses to the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City’s biannual LMI Survey, administered in January 2018. The survey asks respondents about conditions in the previous quarter and year as well as expectations for the next quarter.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City LMI Survey.

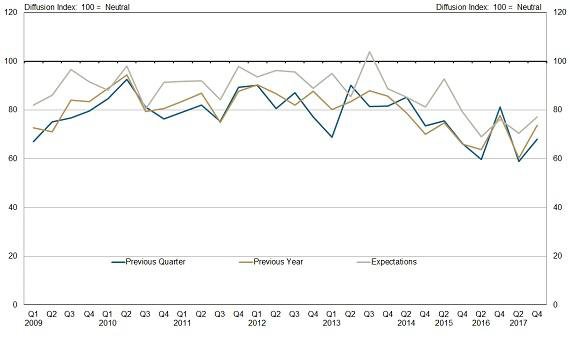

After a decline from 68.1 to 64.4 in the second quarter of 2017, the LMI Financial Condition Index, which is the broadest measure of LMI economic conditions, nudged up to 65.8 (Chart 1).1 Perceptions of economic conditions compared to the previous year, however, rebounded strongly, rising from 55.3 to 65.2.

Chart 1. LMI Economic Conditions Index

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City LMI Survey.

Except for job availability, all indicators remained persistently below the neutral level of 100, reflecting perceptions of continued deterioration in LMI economic conditions. The consensus of survey respondents was that the “recovery” of LMI areas in their cities and towns is lagging. Related to that sentiment were concerns that income inequality was becoming more prominent.

While some contacts stated that wages and disposable income had begun to tick up, most lamented low, stagnant wages and increases in the cost of living, especially in housing and health care. Contacts also expressed uncertainty about government policy, particularly the implications of recent tax legislation for LMI people, but also immigration policy. LMI individuals were said to be increasingly interested in financial literacy and opportunities to better manage their personal finances. This increased interest likely is due in large part to greater efforts to raise awareness of financial literacy issues and to market financial literacy programs.

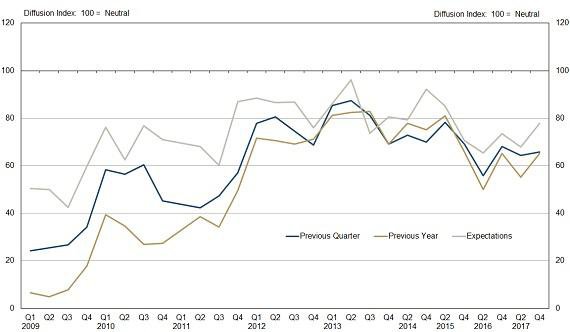

A second index that reflects broad perceptions about economic conditions in LMI communities is the LMI Services Needs Index. Survey respondents are asked whether the demand for their services has increased, decreased, or remained about the same. Because survey respondents provide services to those in need, higher demand is interpreted as an indication that economic conditions are deteriorating and leads to lower index values. The LMI Services Needs Index seems to have plateaued, moving little, on average, over the last several years (Chart 2). The index largely remains around 50. In the most recent survey, 52 percent of respondents reported that the demand for their services had increased in the past quarter, with most of the remainder reporting that demand was about the same. There is arguably a consensus view among our contacts that conditions are deteriorating.

Chart 2. LMI Services Needs Index

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City LMI Survey.

Survey respondents did mention some circumstances that temporarily increased the demand for their services, particularly the especially cold, harsh winter. Weather directly affected demands on organizations that provide utility assistance and shelter, but also indirectly by creating demands on organizations that work to fill the budget gaps of LMI households. By allocating more of household disposable incomes to utilities, fewer resources are available to purchase other necessities, such as medications and nutritious food.

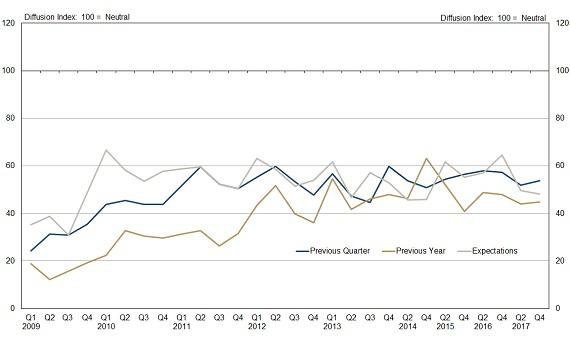

The consensus among survey respondents that economic conditions have continued to deteriorate so far into the recovery from the Great Recession is a conundrum. To gain further insight into this puzzle, we compare the LMI Financial Condition Index to the Conference Board’s Consumer Confidence Index (CCI) (Chart 3). Specifically, we look at consumer confidence among individuals with household incomes less than $35,000. The lowest income bracket CCI (< $15,000 in household income) moves closely with the LMI Financial Condition Index. The other two income-based indexes moved closely as well until around 2015, when confidence began to break away from perceptions built into the LMI Financial Condition Index. The lesson from these comparisons is that the LMI Financial Condition Index may best pick up conditions facing those with the lowest incomes. This phenomenon is sensible, as organizations would be expected to expend much of their effort toward clients with the most modest means.

Interestingly, the temporary rises in the LMI Financial Conditions Index in 2012 and 2014 are coincident with high oil prices, while the breakaway in the confidence index is consistent with the 2015 lull in oil prices. The Tenth District is more oil-dependent than most other parts of the country, and some of our survey respondents often tie LMI economic conditions to performance in the oil and gas sector.

Chart 3. LMI Financial Condition Index and Consumer Confidence Index for Lower Incomes

Sources: The Conference Board; Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City LMI Survey.

I-B. Labor Market Conditions

Basic Labor Market Metrics

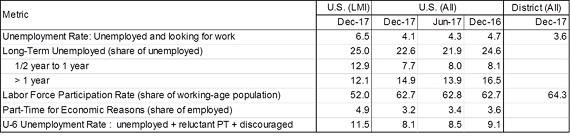

The official unemployment rate, which is the share of the labor force currently out of work but actively seeking employment, was 4.1 percent at the end of the fourth quarter, while the District unemployment rate, which is typically much lower than the national rate, was 3.6 percent. For the LMI labor force, the unemployment rate was 6.5 percent nationally, compared to 7.1 percent in the previous report.2 These and other basic labor market metrics are in Table 2.

Table 2: Labor Market Metrics

Sources: Authors’ calculations using CPS microdata from the National Bureau of Economic Research; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

The U-6 alternative employment rate, which includes discouraged workers and reluctant part-time workers, was 8.1 percent for the entire nation, but 11.5 percent for the LMI. The higher U-6 rate for the LMI largely was driven by those who were employed part time but would like to have had a full-time job. The higher rate of reluctant part-time work in LMI communities is consistent with a higher likelihood that LMI workers would hold jobs paying hourly wages.

Perhaps the most significant labor market metric in the fourth quarter was the lower labor force participation rate in the LMI community of 52 percent, versus 62.7 percent for the entire nation. This phenomenon is addressed in a special topic in this issue.

The black unemployment rate fell sharply over the past year, from 7.9 to 6.8 percent, a historical low. The Hispanic unemployment rate over the same period fell from 5.9 to 4.9 percent, near its historical low of 4.8 percent in November. These data suggest that minorities are sharing in the fruits of robust job growth. Still, gaps remain. In December, the white unemployment rate was 3.7 percent.3 The October 2016 issue of Tenth District LMI Economic Conditions examined persistent unemployment rate gaps across race and ethnicity in more detail as well as opportunities to reduce disparities.4

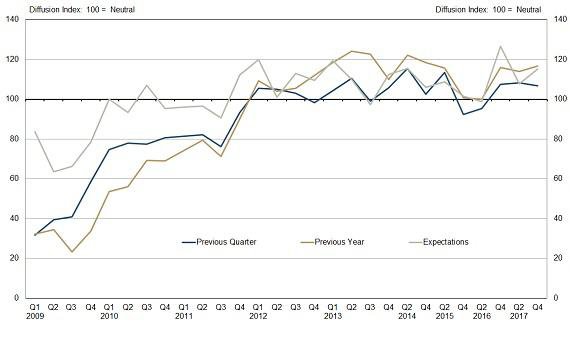

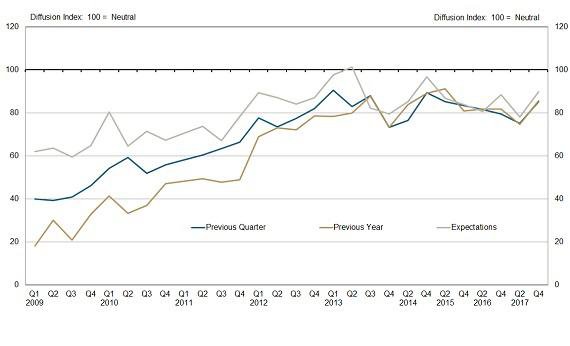

LMI Job Availability Index

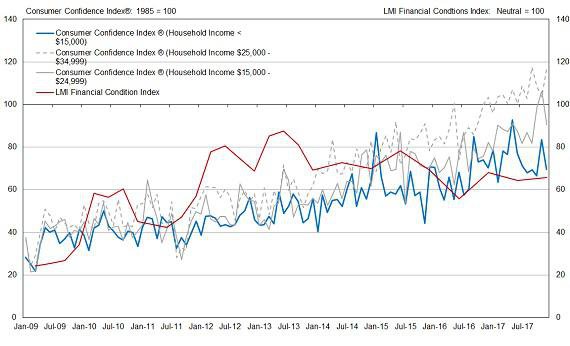

The LMI Job Availability Index was little changed in the fourth quarter, slumping to 106.6 from 108.1 (Chart 4). The year-over-year index increased modestly from 114.0 to 116.6, remaining significantly above neutral. The job availability indexes indicate continued increases in jobs available in LMI communities. Although a lack of qualified workers to fill high-skill positions is a common refrain from policymakers and economic development professionals, survey comments confirm that there remains a number of unfilled low-skill, low-wage jobs. Expectations for the first quarter in 2018 suggest near-term job availability for LMI workers will be even more robust.

Chart 4. LMI Job Availability Index

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City LMI Survey.

Survey respondents noted that there were many job openings in the services sector and also highlighted the transportation sector, specifically, trucking. National data largely support their views.5 Specifically, over the last three years, while total nonfarm employment grew at an annual rate of 1.8 percent, there was much faster growth in many of the sectors that commonly employ LMI workers. Among these were health care and social assistance, which grew 2.6 percent annually, and accommodations and food services, which grew 2.7 percent. Retail trade and transportation saw more moderate employment growth of 1.0 and 1.3 percent, respectively, over the same period.

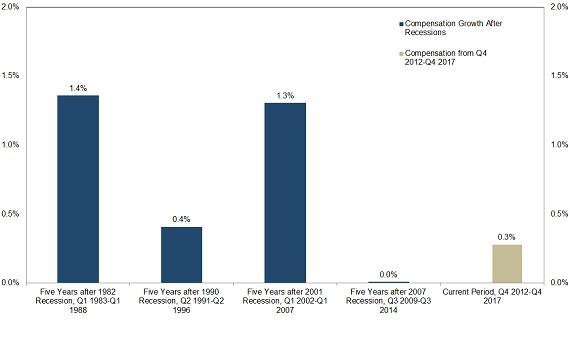

Employment Compensation

Stagnant compensation is a frequent theme in survey comments. Compensation includes not only wages and salaries, but also the financial value of fringe benefits, such as health insurance and paid vacation. These concerns are justified by the data. In the five-year period following the Great Recession, inflation-adjusted growth in employee compensation was about zero (Chart 5). Typically, real compensation growth is robust following a recession. Real employee compensation increased 1.4 percent annually following the 1980-82 recessions and 1.3 percent annually following the 2001 recession. Inflation-adjusted employee compensation growth was less sanguine following the 1990 recession, but still about 0.4 percent annually. Employee compensation now has begun to increase, but at a modest rate of only 0.3 percent annually over the last five years.

Chart 5. Annual Growth in Compensation Five Years After Recessions, Compared to the Present

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics/HAVER Analytics.

I-C. Housing Affordability

A significant number of survey respondents consider housing affordability to be the chief concern facing LMI households. The concern arises largely from inadequate, and in some cases decreasing, stocks of affordable housing, coupled with higher demand in the face of higher market-rate rents in many places.

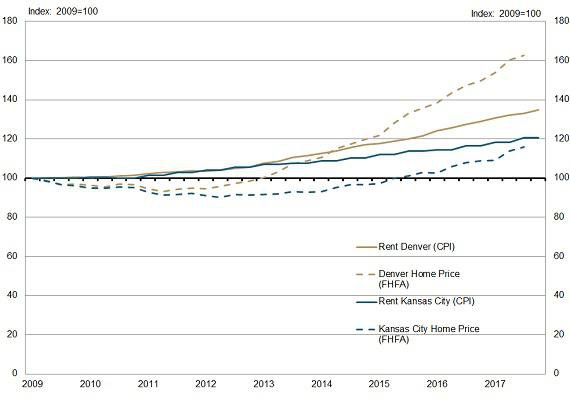

Rents have steadily increased. A common measure of rent over time is the “rent of primary residence” component of the Consumer Price Index (CPI). The data are available for only 25 metropolitan areas but include Kansas City and Denver. CPI rent for Kansas City and Denver has risen consistently for the last several years and have accelerated in recent years (Chart 6). Since 2009, rents have increased 58 percent in Denver and 32 percent in Kansas City. Home prices have followed similar trends. Since 2009, home prices are 68 percent higher in Denver and 20 percent higher in Kansas City.6

Chart 6. Rent Costs and Home Prices in Denver and Kansas City

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Federal Housing Finance Agency, HAVER Analytics

Rent growth has moderated in the past year, especially in Denver. Rents and home prices are important drivers of the LMI Affordable Housing Index. In the fourth quarter, the index rose significantly, but it remains to be seen if this increase pulls the indexes away from their gradual downward path over the last several quarters (Chart 7). The index improved strongly from 58.9 to 68.0, and the year-over-year index saw a significant bounce as well, rising from 60.2 to 73.6. The indexes remain well below neutral, however, indicating deteriorating conditions in the affordable housing sector.

Chart 7. LMI Affordable Housing Index

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City LMI Survey.

A large number of survey contacts reported that not only was affordable housing becoming less available, but the stock of affordable housing already is “nowhere near” where they believe it needs to be. Respondents noted very long waiting lists for affordable housing in many communities, often thousands waiting for a unit. Others reported poor conditions in housing that is affordable, such as a lack of consistently functioning heat or running water, damaged walls and ceilings, and pest infestations.

Gentrification pushing out LMI households was a concern in some areas. Many contacts expressed consternation about once affordable housing properties being sold and converted to market rate units, exacerbating the affordable housing problem.

Recent developments at the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) have led to the implementation of several new rules that affect rents faced by LMI households. Small Area Fair Market Rents offer higher Section 8 voucher credits to people who live in ZIP codes with higher than average rents. Unlike the traditional program, which offers Section 8 voucher credits based on metro area rents, this program seeks to address highly localized poverty.7 In the Tenth District, the program applies only in the Colorado Springs area, but it could expand to other areas.8

In addition, recent developments in Missouri Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC) funding have potential implications for future affordable housing developments. A state commission voted against allocating Missouri’s state LIHTCs for 2018.9 Previously agreed upon state credits and federal credits, however, will continue to be allocated.

I-D. Access to Credit

Similar to other indexes, the LMI Credit Access Index rebounded in the fourth quarter (Chart 8). The credit access index rose to 85.1 from 75.0 in the second quarter, while the year-over-year index rose from 74.7 to 85.6. As is common in survey comments, respondents lamented the continued use of payday lending and other alternative financial products. Some contacts noted that the market has changed somewhat for these products, but mostly to make them easier to access, not to make them more affordable. Other contacts suggested that increased access to credit may not be a “good thing.” Survey respondents also expressed a need for debt consolidation programs for clients.

Chart 8. LMI Credit Access Index

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City LMI Survey.

II. In This Issue

This issue’s special topic centers on reasons for low labor force participation during periods of tight labor markets and employability programs.

II-A. Nonworking Populations in a Tight Labor Market

Since April 2017, the unemployment rate has remained at or below 4.4 percent, the Fed’s projected long-run average.10 These tight labor market periods can be useful for asking why people choose not to work.

Some people do not work because they are unemployed, meaning they are out of work but actively seeking employment, defined as having applied for a job in the previous four weeks. Frictional unemployment describes workers who are searching for new jobs—perhaps a better job or because of a geographic relocation. Frictional unemployment is temporary and accounts largely for the officially unemployed when the unemployment rate is at or below its long-run average. Cyclical unemployment describes workers who are unable to find work due to business conditions. Given that the economy has been trending below the projected long-run average unemployment rate, cyclical unemployment is likely negligible.

At the end of the fourth quarter, the labor force participation rate (LFPR), which measures the share of the population employed or officially unemployed, was 62.7 percent. Thus, at any given time, at least 37 percent of the working-age population were not working and were not officially unemployed—they were not in the labor force. The LFPR was only 52 percent for LMI individuals. There likely are many reasons why working-age people are not in the labor force at any time, but there also may be common trends that help explain the lack of participation.

In our most recent survey, we asked respondents why people in their communities are not working.11 Responses focused on three central themes: child care, health and skills mismatch.

Respondents frequently cited child-care issues, particularly the high cost of child care, as a reason for not working. Specifically, survey respondents reported that clients often must make a choice between working and paying for child care or not working. Oftentimes they choose not to work, feeling that working is not worthwhile financially, given the cost of child care.

While policies exist to assist parents with child-care funding, survey contacts report that qualifications are difficult to meet.12 Moreover, subsidized child care may crowd out informal methods of child care, such as options offered by grandparents or family friends, making little difference on maternal employment rates.13 However, for families where those options are not available, evidence from survey contacts suggests that additional child-care options leads to greater maternal employment.

Also among the most common reasons provided for not working were health issues. Many of those not working are not working because they have a physical disability that prevents them from working. Among adults ages 21-64, about 41 percent of those with a disability work, compared to 79 percent of those without a disability.14 Most of those with qualifying disabilities who do not work receive income through the Social Security Disability Insurance program or the Supplemental Security Income program. Disabled adults with limited incomes may receive disability benefits while working. See the March 2017 issue of Tenth District LMI Economic Conditions for more information on disability payments and labor force participation.

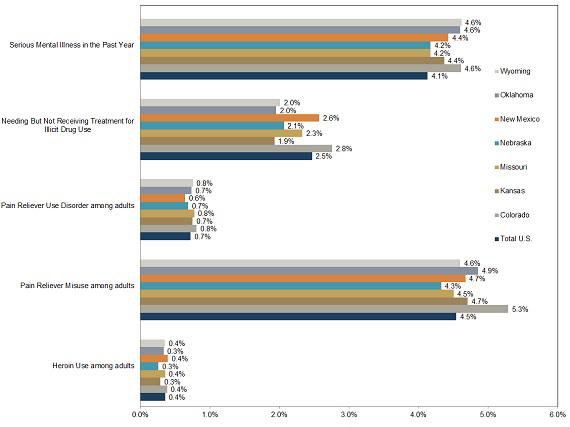

Survey respondents highlighted mental health and drug abuse issues more commonly than physical disabilities, likely because these issues are an increasing problem. Data for 2015-16 from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration highlight the scope of the issue within the Tenth District (Chart 9). All District states were near or above the national average for share of the population suffering from serious mental illness. A number of District states also suffer disproportionately from drug-related problems such as the misuse of pain relievers or illicit drug use, particularly Colorado.

Chart 9. Tenth District Health Metrics

Note: Percentages indicate estimates for the share of the population.

Source: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

II-B. Employability Programs

A lack of technical skills and even basic skills hinders many people in finding work or advancing in their job. A report by the Conference Board indicates employers find that many new entrants into the workforce are skill-deficient.15 To remedy the gap between potential employees and employers, workforce training programs offer assistance with these types of skills. While some are state-sponsored programs, local organizations, community colleges and private companies implement similar programs.

To understand what programs exist in the Tenth District and traits shared by successful programs, the survey asked a special question on workforce training programs. Two primary themes emerged from user comments: mentorship programs and apprenticeships. Mentorships focus on soft-skills training, while apprenticeships focus on technical and job-specific skills.

Several respondents favored highly involved mentoring programs. Mentorship has been shown to provide protégés with technical and psychological support, improving job performance.16 There also are many potential psychosocial benefits of mentorship, including friendship and role modeling.17 Former protégés who had a positive mentorship experience also are more likely to become mentors themselves.18

According to respondents, a focus in hard skills, along with hands-on guidance, leads to successful apprenticeships. Comments noted that apprenticeships are most effective in certain sectors, such as construction, IT and warehouse work.

Respondents also noted several traits shared by successful workforce training organizations. Perhaps most important to contacts was that workforce training programs be targeted. Targeted programs allow for specialization and can use resources most relevant to specific demographic groups or for specific career paths. For example, the U.S. Department of Labor’s Long-Term Care Regional Apprenticeship Program targets career opportunities for nursing and home care.19 Coupled with evidence that older workers are a valuable untapped resource for primary care frontline work, state programs have utilized the Senior Community Service Employment Program as funding to provide training for older adults for jobs in home primary care.20

Another commonly cited successful strategy was employer-informed programs. Through understanding what skills are most valuable to the workforce, employers can assist with training opportunities and prepare a workforce tailored to their needs. This can also lead to increased job satisfaction, especially in the case of on-the-job training.21 Finally, respondents noted that holistic workforce training programs aid clients. These include the incorporation of financial assistance, life coaching and health benefits.

Endnotes

-

1

The question asks “How has the financial well-being (e.g., ability to fund basic needs, debt burden, etc.) of low- and moderate-income people changed relative to the previous quarter?”

-

2

Separating unemployment from income is problematic in that employment and income are closely tied and unemployed people generally have lower incomes (although they may receive unearned income, such as unemployment compensation). In discussing labor market metrics for LMI workers, we consider an individual as being LMI if s/he lives in a family with income less than $60,000. In 2016, the 40th percentile in income, which corresponds with 80 percent of the median, was $57,944. We do not have sufficient data to produce an LMI unemployment rate for the District or individual states.

-

3

Bureau of Labor Statistics, Table A-2 “Employment status of the civilian population by race, sex, and age.” Available at External Linkhttps://www.bls.gov/webapps/legacy/cpsatab2.htm and Table A-3, “Employment status of the Hispanic or Latino population by sex and age.” Available at External Linkhttps://www.bls.gov/webapps/legacy/cpsatab3.htm The white unemployment rate includes Hispanics/Latinos who identify as white.

- 4

-

5

Data are from the Current Employment Statistics series (CES)/Haver Analytics. Available at External Linkhttps://www.bls.gov/ces/#data

-

6

Elsewhere in the District, homes prices have increased 22 percent in Oklahoma City, 21 percent in Omaha, 14 percent in Tulsa and 31 percent in Colorado Springs.

-

7

See “HUD’s Proposed Rule on Small Area Fair Market Rents” Available at External Linkhttps://www.huduser.gov/portal/datasets/fmr/fmr2016p/SAFMR-OnePage-Summary.pdf

-

8

See “Key Aspects of HUD’s Final Rule on Small Area Fair Market Rents.” Available at External Linkhttps://www.huduser.gov/portal/datasets/fmr/fmr2016f/SAFMR-Key-Aspects-of-Final-Rule.pdf

-

9

See Novogradac Journal of Tax Credits, “Low-Income Housing Tax Credits News Briefs - January 2018.” Available at External Linkhttps://www.novoco.com/periodicals/news/low-income-housing-tax-credits-news-briefs-january-2018

-

10

See Federal Reserve Board, December 2017, “Federal Reserve Board and Federal Open Market Committee release economic projections from the Dec. 12-13 FOMC meeting.” Available at External Linkhttps://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/monetary20171213b.htm

-

11

The question asked was “Although unemployment rates have improved considerably, a number of people remain out of work. What are the primary reasons jobless members of your community are not working? Please explain.”

-

12

A list of programs can be found through Childcare Aware. Available at External Linkhttp://childcareaware.org/families/paying-for-child-care/federal-state-child-care-programs/

-

13

Tarjei Havnes and Magne Mogstad, 2011, “Money for Nothing? Universal Child Care and Maternal Employment,” Journal of Public Economics, 95(11-12), 1455-1465; Tarjei Havnes and Magne Mogstad, 2015, “Is Universal Child Care Leveling the Playing Field?” Journal of Public Economics, 127, 100-114.

-

14

U.S. Census Bureau, “Nearly 1 in 5 People Have a Disability in the U.S., Census Bureau Reports.” News Release. Available at https://www.census.gov/newsroom/releases/archives/miscellaneous/cb12-134.html

-

15

Jill Casner-Lotto and Linda Barrington, 2006, “Are They Really Ready to Work? Employers’ Perspectives on the Basic Knowledge and Applied Skills of New Entrants to the 21st Century U.S. Workforce.” Partnership for 21st Century Skills, Washington, D.C.

-

16

Belle Rose Ragins and Terri A. Scandura, 1999, “Burden or Blessing? Expected Costs and Benefits of Being a Mentor,” Journal of Organizational Behavior, 20(4), 493-509.

-

17

Tammy D. Allen et al., 2004, “Career Benefits Associated with Mentoring for Protégés: A Meta-Analysis,” Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(1), 127-136.

-

18

Op. cit., Ragins and Scandura.

-

19

Robyn Stone and Mary F. Harahan, 2010, “Improving the Long-Term Care Workforce Serving Older Adults, Health Affairs, 29(1), 109-115.

-

20

Ibid.

-

21

Steven W. Schmidt, 2007, “The Relationship Between Satisfaction with Workplace Training and Overall Job Satisfaction,” Human Resource Development Quarterly, 18(4), 481-498. On-the-job training is related to overall organizational support, which has also been linked to job satisfaction. See Robert Eisenberg et al., 1997, “Perceived Organizational Support, Discretionary Treatment, and Job Satisfaction,” Journal of Applied Psychology, 82(5), 812- 820.