Beginning with this issue, the structure of the report has been updated. Specifically, the report now has two separate sections. The first covers LMI Survey responses and external data typically published in Tenth District LMI Economic Conditions. Readers can expect the same metrics to be updated in every issue. Special topics will be covered separately in the second section. The July 2017 LMI Survey used a much larger sample, leading to a substantial increase in survey responses.

I. Economic Update for LMI Communities

Section I-A provides a general assessment of economic conditions in low- and moderate-income (LMI) communities by evaluating two relatively broad questions in the LMI Survey: one that asks for an overall perception of economic conditions and one that asks about the demand for respondents’ services. Section I-B highlights responses from the LMI Survey’s question about job availability and provides the report’s standard labor-market metrics. Finally, Sections I-C and I-D explore affordable housing issues and access to credit, respectively. Section II presents findings from LMI Survey special questions and other data sources related to two special topics: wages and minimum wages and the Earned Income Tax Credit and the disposition of tax refunds by LMI filers.

I-A. General Assessment

Most indicators of economic and financial conditions in low- and moderate-income (LMI) communities declined from the prior survey. Except for the job availability index, all indicators have remained below the neutral value of 100, which implies deteriorating conditions. The indexes, which are diffusion indexes (see box), were computed from responses to the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City’s biannual LMI Survey, administered in July 2017 (July survey). The survey asks respondents about conditions in the previous quarter and year as well as expectations for the next quarter. LMI individuals, families or households are those with incomes less than 80 percent of area median income. For those in urban areas, area median income is the value for the metropolitan area; for those in rural areas, it is state median income.

Diffusion Indexes

Service providers to the LMI population respond to each LMI Survey question by indicating whether conditions during the current quarter were higher (better) than, lower (worse) than or the same as the previous quarter (quarterly index) or year (year-to-year index). Providers also are asked what they expect conditions to be in the next quarter. Diffusion indexes are computed by subtracting the percent of service providers that responded lower (worse) from the percent that responded higher (better) and adding 100. The exception is the LMI Services Needs Index, which is computed by subtracting the percent of service providers that responded higher from the percent that responded lower and adding 100 to show that higher needs translate into lower numbers for the index. A reading below 100 indicates the overall assessment of respondents is that conditions are worsening. For example, an increase in the index from 70 to 85 would indicate conditions are still deteriorating, by consensus, but that fewer respondents are reporting worsening conditions. Any value above 100 indicates improving conditions, even if the index has fallen from the previous quarter or year. A value of 100 is neutral. A complete table of responses, along with recent survey history, is provided in Table 1.

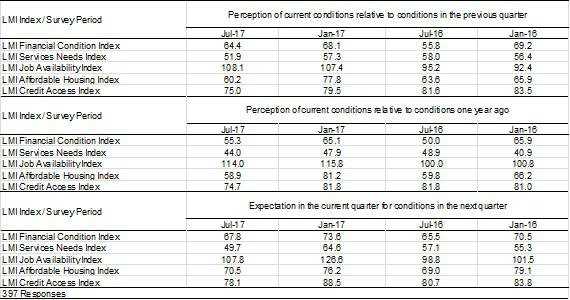

Table 1: Diffusion Indexes For Low- And Moderate- Income Survey Responses

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City LMI Survey

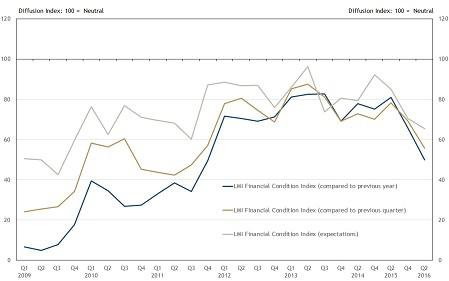

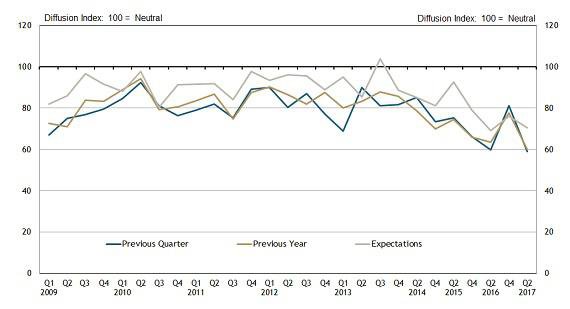

Following a significant increase from 55.8 to 68.1 in the January 2017 survey, the LMI Financial Condition Index, the broadest measure of economic conditions in the LMI community, retreated moderately in the July survey to 64.4 (Chart 1) (all references to an index are current conditions relative to the previous quarter unless stated otherwise)._ The drop came from a lower share of survey respondents that reported improving conditions. Perceptions of economic conditions relative to one year ago dropped more significantly, from 65.1 to 55.3. Both indexes of financial conditions are well below the neutral reading.

Chart 1: LMI Financial Condition Index

Notes: LMI Survey data were collected quarterly prior to 2014. For details on the computation of diffusion index values, see box inset in the text. The survey pool was expanded substantially for the July 2017 survey, and therefore results may be less comparable to data from previous quarters.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City LMI Survey

The decrease in the LMI Financial Conditions Index is consistent with other indicators, most of which also declined. In general, the declines in the indexes from the July survey appear, in part, to be bounce-backs from gains reported in the January survey relative to the July 2016 survey. Thus, the declines from the January survey appear to be more pronounced.

The LMI Services Needs Index has remained well below neutral since the survey started in 2009 (Chart 2). The index fell from 57.3 in the January survey to 51.9 in the July survey (because survey respondents provide community and social services, higher demand is interpreted as an indication that economic conditions are deteriorating, and thus higher demand leads to lower index values). Only 4 percent of respondents reported that demand had decreased, while 52.2 percent reported an increase in demand for their services (the remainder reported no change in conditions). The index reflecting expectations for demand in the next quarter fell sharply from 64.6 to 49.7.

Chart 2: LMI Services Needs Index

Notes: LMI Survey data were collected quarterly prior to 2014. For details on the computation of diffusion index values, see box inset in the text. The survey pool was expanded substantially for the July 2017 survey, and therefore results may be less comparable to data from previous quarters.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City LMI Survey

I-B. Labor Market Conditions

LMI Job Availability Index and Survey Comments

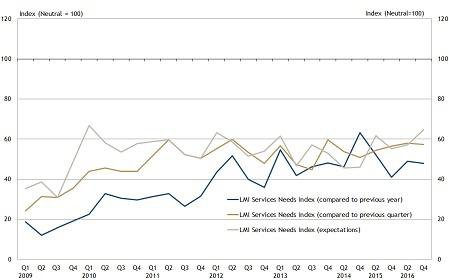

The LMI Job Availability Index changed little in the July survey, moving from 107.4 to 108.1. Its value, slightly above neutral, indicates continued modest improvement in job availability in the Tenth District for LMI workers (Chart 3). The consensus of survey respondents was that more jobs would be available in the near term as well, but fewer contacts held that view than in the last survey, pushing the “expectations index” down sharply from 126.6 to 107.8.

Chart 3: LMI Job Availability Index

Notes: LMI Survey data were collected quarterly prior to 2014. For details on the computation of diffusion index values, see box inset in the text. The survey pool was expanded substantially for the July 2017 survey, and therefore results may be less comparable to data from previous quarters.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City LMI Survey

Many respondents commented that ample jobs were available in their areas for LMI workers but that wages were very low and insufficient to support an individual or family—a common ongoing refrain in survey responses. Many of these jobs were in the hospitality (especially food service) and retail sectors. There were significantly more comments about legislation and regulations in the July survey than in previous surveys. Many contacts suggested that minimum wages should be higher (there was a special question in the July survey on minimum wage, which is discussed in detail in the special topics section below). Also noted were efforts to require paid sick leave and other benefits. While survey respondents’ comments generally seemed to support these kinds of changes in labor regulations, some contacts expressed concerns that these efforts would result in job losses and reduced work hours.

Survey contacts noted that high-paying jobs were also available (generally in larger urban areas of the District, especially Denver), but that they require highly skilled workers, and LMI workers generally would not qualify. Indeed, some respondents reported that many of their constituents lack even the most basic skills required to get and retain a job, such as presenting oneself appropriately to an employer, being punctual and reliable and relating well to co-workers.

Another well-documented factor is job polarization, which helps explain survey contacts’ experiences with low-skill and high-skill job availability and the pattern of wage growth. Job polarization generally is growth, possibly rapid, in high-skilled and low-skilled jobs with a “vanishing middle.”_ Many analysts have put polarization at the center of discussions about rising wage and income inequality._ However, some analysts recently have assessed the availability of “good jobs” for those with lower skills (specifically, those without college degrees). A recent report from the Center on Education and the Workforce at Georgetown University suggests “there are still 30 million good jobs in the U.S. that pay well without a BA” (the jobs pay a minimum of $35,000 annually but an average of $55,000 annually)._ Further, the Federal Reserve Banks of Atlanta and Philadelphia have been identifying “opportunity occupations,” or “jobs that pay workers at least the national annual median wage . . . and are generally accessible for a worker without a bachelor’s degree.”_ They argue that “roughly 27% of all employment can be classified as opportunity occupations.” Interestingly, Kansas City was identified as the major metropolitan area with the largest employment share of opportunity occupations at 36 percent.

Labor Market Metrics

The official U.S. unemployment rate (U-3)—the share of the labor force that currently is not working but has actively sought employment in the last four weeks—was 4.4 percent in June (Table 2). The Tenth District unemployment rate in June was 3.7 percent. Both levels are considered to be full employment._

The corresponding unemployment rate for LMI workers was 7.1 percent nationally._ This number is consistent with unemployment rates for those with a high school diploma (5.3 percent) or less (9.9 percent). Limited formal education is an endemic problem for the LMI in securing jobs, better jobs and better wages, as commonly noted in LMI Survey responses. In addition, the unemployment rate for those who typically work in nonprofessional service occupations was 5.8 percent in the latest available data (2016) (8.7 percent for food service), compared to 2.5 percent in managerial and professional occupations._

An alternative unemployment rate (U-6) gives a broader picture of unemployment by including discouraged workers (those who want a job but have given up their search because they think it futile) and those who are working part time because they are unable to find a full-time job in prevailing business conditions._ The U-6 unemployment rate was 8.6 percent nationally in June. The U-6 unemployment rate for LMI workers was considerably higher at 12.7 percent. The sizeable gap may reflect that many of the jobs for which most LMI workers qualify are part-time jobs.

Long-term unemployment, the share of unemployed out of work more than 26 weeks, continued to fall—from 24.6 percent to 21.9 percent since January—but remains historically high, especially at this stage of recovery from the Great Recession._

Challenges to the LMI labor market extend beyond unemployment to “underemployment,” broadly defined as working in an occupation that requires education, training and/or experience below those attained by the worker._ While this problem is most common among young college graduates, they may be among the LMI population with underemployment.

In June 2017, the national labor force participation rate (LFPR) was 62.8 percent, little changed from December 2016 and still well below its average pre-recession level of about 66 percent. While the LFPR has become more procyclical since the 1980s (declines in tandem with economic activity), the continued historically low LFPR may persist with structural factors, particularly retiring baby boomers._

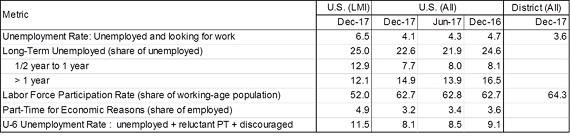

Table 2: Labor Market Metrics

Sources: Authors’ calculations; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics; National Bureau of Economic Research (Current Population Survey microdata)

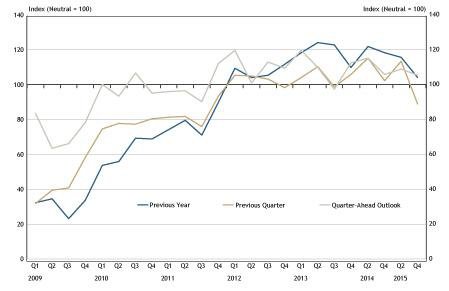

I-C. Housing

The LMI Affordable Housing Index fell sharply from 77.8 in the January LMI Survey to 60.2 in the July survey (Chart 4). The index measuring perceptions relative to one year ago fell even more sharply from 81.2 to 58.9, continuing a downward trend from 2013. The indexes remain well below neutral, which indicates that most survey contacts believe that affordable housing is becoming less available.

Chart 4: LMI Affordable Housing Index

Notes: LMI Survey data were collected quarterly prior to 2014. For details on the computation of diffusion index values, see box inset in the text. The survey pool was expanded substantially for the July 2017 survey, and therefore results may be less comparable to data from previous quarters.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City LMI Survey

Many of the comments from the survey associated reduced availability of affordable housing to increasing rents, making market-rate housing unaffordable for more people._ Echoing comments about job availability, many contacts noted that wages have not kept pace with increasing housing costs.

Reports of new and rehab construction varied extensively, but in many of the comments reporting significant new construction of affordable housing it was noted that the demand for affordable housing still outstrips supply, even as the supply increases. Some respondents stated that waiting lists for assisted housing were long—in some cases a year or more. Some reported that construction of rental properties was increasing, but only well outside the urban core where most LMI households live. Assessments of the availability of affordable housing in rural areas were mixed.

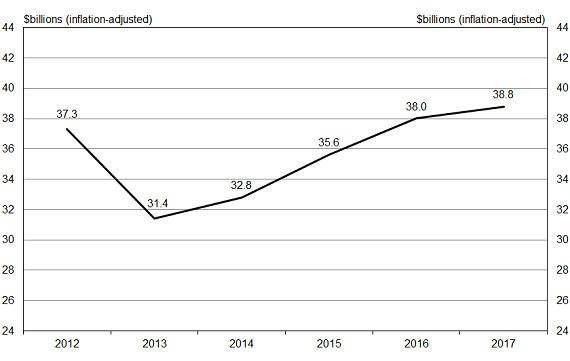

A few of the survey comments lamented decreases in federal funding, many specifically noting the Department of Housing and Urban Development. Final budget appropriations from 2012-17 show relatively stable funding of HUD (Chart 5), but the Trump administration’s budget for fiscal year 2018 calls for a $6 billion decrease in HUD funding, mostly in housing programs and planning and community development. Final fiscal year 2018 appropriations likely will not be known for some time. In Congress, a 2018 budget resolution was approved by the full committee on July 19, 2017, and passed by House of Representatives on Sept. 14, 2017, but, as of writing, the budget bill had not been introduced in the Senate._

Following the election of President Trump and subsequent market reaction, Low Income Housing Tax Credit pricing experienced high volatility earlier this year, but the market has since stabilized._

Chart 5: Department of Housing and Urban Development Final Appropriations

Notes: 2012 and 2013 appropriations, as shown in the table, were reduced by $0.1 billion and $15.2 billion, respectively because they represented disaster funding not in the finalized budget. Actual budget figures were $37.43 billion and $46.63 billion. The 2016 number was reduced by $0.8 billion due to budget offsets.

Source: Congressional Research Service, June 23, 2017, Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD): FY2017 Appropriations.

I-D. Access to Credit

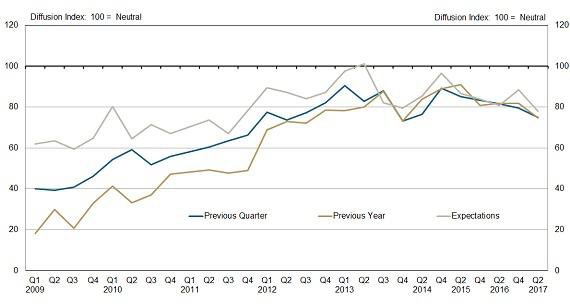

Indicators of access to credit (perception relative to the previous quarter and year and expectations for the following quarter) declined moderately, remaining relatively stable in the July Survey and continued to indicate an overall assessment of reduced access to credit (Chart 6). The LMI Credit Access Index fell from 79.5 in the January 2017 survey to 75 in the July survey (quarter-over-quarter). The index reflecting expectations for the upcoming quarter declined over 10 points, from 88.5 to 78.1.

The indexes increased significantly and consistently from the start of the survey in the first quarter of 2009 through 2013, but since then have fluctuated around 80. Comments over the history of the survey have been consistent with this pattern: following the recession, there were improvements in credit standing and willingness to lend by banks. Since then, not much has changed, including the proliferation of payday and other alternative financial institutions. Indeed, credit scores now are starting to decline for some LMI constituents.

Despite the generally negative tenor of the comments, some survey contacts reported they had seen a significant increase in “affordable” alternative loan products (usually small-dollar loan programs offered by financial institutions or nonprofit loan funds). What is missing, respondents said, is scale, as most of these programs are limited in available funds and often are pilot projects.

Chart 6: LMI Credit Access Index

Notes: LMI Survey data were collected quarterly prior to 2014. For details on the computation of diffusion index values, see box inset in the text. The survey pool was expanded substantially for the July 2017 survey, and therefore results may be less comparable to data from previous quarters.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City LMI Survey

II. In This Issue

This issue’s special topics center on wages—particularly, minimum wages—and the disposition of income tax refunds by LMI filers.

II-A. Wages and Minimum Wages

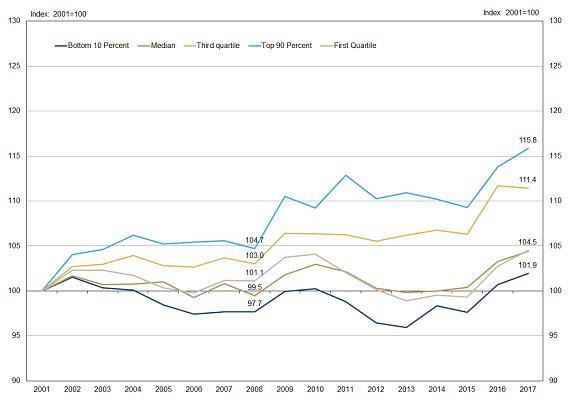

Throughout respondents’ comments in the LMI Survey were concerns about wage growth that was insufficient to pay for basic needs, especially housing and transportation. Chart 7 shows an index representing usual weekly earnings relative to 2001 for several income classes, adjusted for inflation. Earnings for the top 10 percent of wage earners has increased 15.8 percent in inflation-adjusted terms since 2001, compared to only 1.9 percent for the bottom 10 percent and 4.5 percent for the bottom quartile. From the trough of earnings during the recession (2008), earnings increased 10.6 percent for the top 10 percent of wage earners, but 4.3 percent for the bottom 10 percent and 3.3 percent for the bottom quartile. Over time, these marginal differences in earnings can lead to large income disparities between worker quantiles.

Chart 7: Usual Weekly Earnings Quantiles

Source: Household Survey, U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics/HAVER Analytics

With relatively slow earnings growth in the last several years, communities and public officials have looked toward the minimum wage as a tool for inducing wage growth. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), about 2.2 million workers in 2016 were paid at or below the federal minimum wage._

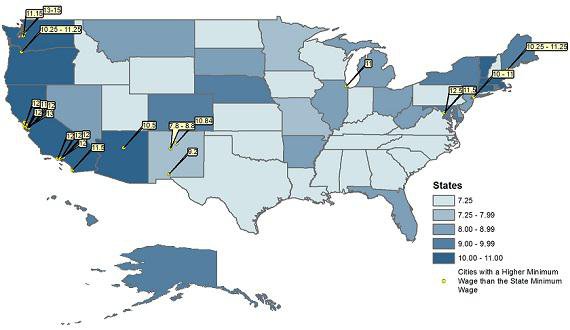

States and municipalities increasingly have been legislating higher minimum wages, partially as a response to a federal minimum wage that has been $7.25 an hour since July 2009. States and cities have cited increased costs of living, increasing income inequality, equity and regional differences in cost of living as reasons for increasing the minimum wage. Minimum wage increases became more frequent in recent years, especially on the West Coast and in the Northeast. Map 1 shows minimum wages across the country and municipalities that have raised their minimum wage above the state’s minimum wage.

Map 1: State and Local Minimum Wages

Source: Economic Policy Institute, National Conference of State Legislatures

In some cases, states or cities adopted substantially higher minimum wages. In California, the state minimum wage is $10.50 and is progressing to $15 by 2022. In Oregon, the minimum wage is $10.25 (nonrural) at the state level and $11.25 in Portland. In Washington, the minimum wage is $11, but is $15 in Seattle for businesses with more than 500 employees and a declining scale for businesses with fewer employees. Many Northeast states have minimum wages of more than $10/hour.

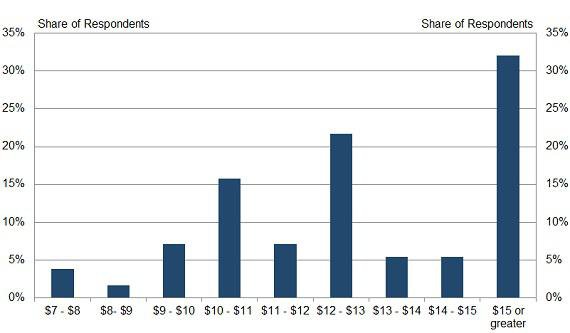

Respondents to the LMI Survey were asked what they believe the minimum wage should be and what they expect to be the consequences of increasing the minimum wage. Chart 8 shows a histogram of suggested minimum wages from LMI Survey respondents. Among those who responded to the special question on minimum wages, more than 30 percent suggest a wage of $15 or more; a few suggested minimum wages as high as $25. Currently, the highest minimum wage in the United States is $15. More than 70 percent of respondents argued for a minimum wage of $11 or more. Some survey contacts suggested that effective (in the sense of raising the wage) minimum wage legislation must happen at the federal level because many states and cities appear unlikely to ever raise the minimum wage, ostensibly because of political factors.

Chart 8: LMI Survey Respondents' Suggested Minimum Wage

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City LMI Survey

II-B. The Earned Income Tax Credit and the Disposition of Tax Refunds

Earned Income Tax Credit

A tax policy unique to LMI populations is the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC). The EITC allows for qualifying workers who earned income during the past year to receive a large tax credit._ The maximum credit, depending on the number of children in a household, ranges from $506 to $6,269._ Workers can receive the refund as either a lump sum payment or installments during the year, although research suggests the lump sum is the more popular choice._ The EITC is a refundable tax credit, meaning that one does not have to have any tax liability to offset the credit.

Most filers who claim the EITC have low tax liabilities, and thus a majority of EITC claimants receives the credit through a tax refund. State EITC programs, where they exist, typically operate in a similar fashion, although some states provide nonrefundable tax credits. All states in the Tenth District except Missouri and Wyoming have a state EITC._

The economic motive of the EITC is to encourage LMI populations to participate in the labor market. The net effect on employment, however, is conceptually ambiguous: the subsidy makes the value of work higher, which should encourage working, but a worker may be inclined to work less because he could earn the same income with fewer hours of work._ Consider a worker earning $7.25 an hour and working 20 hours a week for a gross weekly wage of $145. An increase in the minimum wage to $10 would make work more attractive because not working (leisure) is more expensive. However, the worker now could earn $145 by working 14½ hours and therefore can work less and maintain current income.

Applicants must apply to the program, which can lead to qualified candidates not receiving a refund if they fail to apply. In the Tenth District, the number of applicants who are qualified but do not receive the federal EITC ranges from 26.1 percent in Colorado to 17.9 percent in New Mexico._ The estimated fiscal cost of the EITC for the 2016 tax year was $67 billion._

Disposition of Tax Refunds

Many analysts and organizations have sought to understand how tax refunds typically are used._ Studies suggest the most common disposition of tax refunds is to pay down debt, accumulate savings or make major purchases.

Respondents to the LMI Survey were asked about how LMI families typically use their tax refunds, and responses were similar to findings for the population at large.

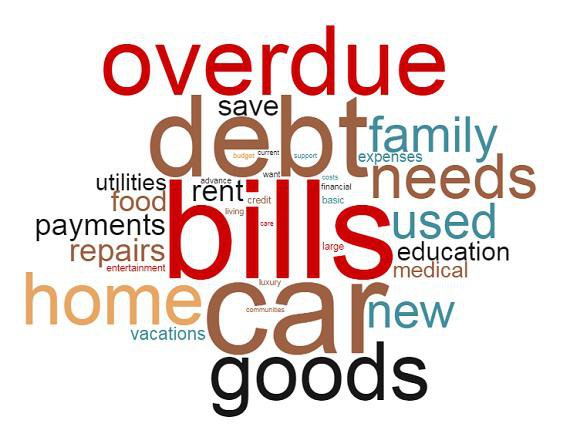

Figure 1 shows a word cloud of respondents’ answers to the special question. “Bills” was the most frequent word in the responses. Survey comments noted that tax returns often went to past-due bills or advance payments, as reflected by the terms “overdue” and “advance.” These bills commonly related to necessities such as housing or energy. “Cars” were the second-most frequent word in the responses. Respondents described two scenarios for car purchases: as essential for transportation and as a nonessential luxury purchase. More respondents noted that these funds went to used cars more than new cars. “Car repairs” also was prevalent among the responses. Finally, “Debt” was the third-most frequent word in the responses. Debt often was medical or education-related, as reflected in the word cloud. Beyond the three largest word categories, respondents listed both essential and nonessential items such as home-related furnishings, vacations and food. Survey contacts expressed concerns about nonessential purchases, which could result in future costs. For example, cars purchased with a tax refund may result in repair costs later in the year.

Figure 1: Word Cloud Showing How Tax Refunds are Used by LMI Tax Filers

Notes: A word cloud creates a visual representation of frequency of words in a text document. The size of each word represents frequency in the document. Limitations include the differentiation of word tenses, adjectives for the items discussed, words used sparingly and words addressing the question itself. Authors edited the original word cloud to remove errors, aggregate responses differing only by sentence structure (like adjective, adverb, etc.) and words that appeared in the text document fewer than five times.

Sources: Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City and wordclouds.com.

Endnotes

-

1

The questions asks “How has the financial well-being (e.g., ability to fund basic needs, debt burden, etc.) of low- and moderate-income people changed relative to the previous quarter?”

-

2

See Didem Tüzemen and Jonathan Willis, 2013, “The Vanishing Middle: Job Polarization and Workers’ Response to the Decline in Middle-Skill Jobs,” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Economic Review, First Quarter, pp. 5-32. Available at https://www.kansascityfed.org/~/media/files/publicat/econrev/econrevarchive/2013/1q13tuzemen-willis.pdf.

-

3

See, for example, David Autor, 2011, “The Polarization of Job Market Opportunities in the U.S. Labor Market: Implications for Employment and Earnings,” Community Investments, Fall, pp. 11-41. Available at External Linkhttp://www.frbsf.org/community-development/files/CI_IncomeInequality_Autor.pdf.

-

4

Anthony P. Carnevale, Jeff Strohl, Ben Cheah and Neil Ridley, 2017, “Good Jobs That Pay without a BA,” Center on Education and the Workforce, Georgetown University. Available at External Linkhttps://goodjobsdata.org/wp-content/uploads/Good-Jobs-wo-BA.pdf.

-

5

See the infographic at External Linkhttps://www.philadelphiafed.org/-/media/community-development/publications/special-reports/identifying_opportunity_occupations/identifying_opportunity_occupations_infographic_pdf.

-

6

Full employment” is essentially a lack of cyclical unemployment; that is, unemployment due to business conditions. For a full, technical, but approachable, discussion, see Laurence Ball and N. Gregory Mankiw, 2002, “The NAIRU in Theory and Practice, Journal of Economic Perspectives, vol. 16, no. 4, pp. 115-136.

-

7

Separating unemployment from income is problematic in that employment and income are closely tied and unemployed people generally have lower incomes (although they may receive unearned income, such as unemployment compensation). In discussing the labor market metrics for LMI, we consider an individual as being LMI if s/he lives in a family with income less than $60,000. In 2016, the 40th percentile in income, which corresponds with 80 percent of the median, was $57,944. We do not have sufficient data to produce an LMI unemployment rate for the District or individual states. All LMI figures were calculated by the authors using individual-level data from the Census Bureau’s Current Population Survey.

-

8

Complete data are available at External Linkhttps://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat25.htm. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics releases the occupational unemployment data as annual averages, and 2016 is the latest available. Data for 2017 will be available in January 2018.

-

9

See U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Employment Situation, Table A-15, “Alternative Measures of Labor Underutilization.” Available at External Linkhttp://www.bls.gov/news.release/empsit.t15.htm.

-

10

Additional details of the recent pattern in LFPR can be found in the March 29, 2017, issue of “Tenth District LMI Economic Conditions,” available at https://www.kansascityfed.org/research/indicatorsdata/lmieconomicconditions/articles/2017/lmi-economic-conditions-03-17.

-

11

For additional details and background on underemployment, particularly recent college graduates, see the March 29, 2017, issue of “Tenth District LMI Economic Conditions,” available at External Linkhttps://www.kansascityfed.org/research/indicatorsdata/lmieconomicconditions/articles/2017/lmi-economic-conditions-03-17. See also Bureau of Labor Statistics, “Labor Force Characteristics.” Available at External Linkhttps://www.bls.gov/cps/lfcharacteristics.htm; Federal Reserve Bank of New York, “The Labor Market for Recent College Graduates.” Available at: External Linkhttps://www.newyorkfed.org/research/college-labor-market/college-labor-market_underemployment_rates.html

-

12

See Willem Van Zandweghe, 2017, “The Changing Cyclicality of Labor Force Participation,” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Economic Review, Third Quarter. Available at https://www.kansascityfed.org/~/media/files/publicat/econrev/econrevarchive/2017/3q17vanzandweghe.pdf.

-

13

For a recent discussion of rent affordability, including LMI households, see Kelly D. Edmiston, 2016, “Residential Rent Affordability across U.S. Metropolitan Areas,” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Economic Review, Fourth Quarter, pp. 5-27. Available at https://www.kansascityfed.org/~/media/files/publicat/econrev/econrevarchive/2016/4q16edmiston.pdf.

-

14

See Committee for a Responsible Budget, “Appropriations Watch: 2018,” available at External Linkhttp://www.crfb.org/blogs/appropriations-watch-fy-2018. Until a final budget agreement is passed in both chambers of Congress and signed by the president, budget authority has been maintained by continuing resolutions.

-

15

See Teresa Garcia, “LIHTC Market Gets ‘Back to Equilibrium’ after ‘Intense’ 2016.” Novogradac & Co. LLP, 2017. Available at External Linkhttps://www.novoco.com/periodicals/articles/lihtc-market-gets-back-equilibrium-after-intense-2016

-

16

See U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Household Data, Table 44, “Wage and Salary Workers Paid Hourly Rates with Earnings at or Below the Prevailing Federal Minimum Wage by Selected Characteristics.” Available at External Linkhttps://www.bls.gov/cps/cpsaat44.htm

-

17

See Ekaterina Jardim et al., “Minimum Wage Increases, Wages, and Low-Wage Employment: Evidence From Seattle.” NBER Working Paper No. 23532, 2017. Available at External Linkhttps://evans.uw.edu/sites/default/files/NBER%20Working%20Paper.pdf. See also Reich et al., “Seattle’s Minimum Wage Experience 2015-16.” University of California -Berkley, Center on Wage and Employment Dynamics, 2017. Available at: External Linkhttp://irle.berkeley.edu/files/2017/Seattles-Minimum-Wage-Experiences-2015-16.pdf

-

18

See IRS, “Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC).” Available at External Linkhttps://www.irs.gov/credits-deductions/individuals/earned-income-tax-credit. Requirements for the EITC can be found at: External Linkhttps://www.irs.gov/credits-deductions/individuals/earned-income-tax-credit/do-i-qualify-for-earned-income-tax-credit-eitc

-

19

See IRS, “2016 EITC Income Limits, Maximum Credit Amounts and Tax Law Updates.” Available at External Linkhttps://www.irs.gov/credits-deductions/individuals/earned-income-tax-credit/eitc-income-limits-maximum-credit-amounts

-

20

See Jennifer L. Romich and Thomas Weisner, “How Families View and Use the EITC: Advance Payments.” National Tax Journal, Vol. 53 No. 4, December 2000. Available at External Linkhttps://www.jstor.org/stable/41789516

-

21

See Jessica Hathaway, “Tax Credits for Working Families: Earned Income Tax Credits (EITC).” National Conference of State Legislatures, 2017. Available at External Linkhttp://www.ncsl.org/research/labor-and-employment/earned-income-tax-credits-for-working-families.aspx

-

22

See Bruce D. Meyer, “The Effects of the Earned Income Tax Credit and Recent Reforms.” National Bureau of Economic Research, Tax Policy and the Economy, Volume 24, 2010. Available at External Linkhttp://www.nber.org/chapters/c11973

-

23

See Jessica Hathaway, “Tax Credits for Working Families: Earned Income Tax Credits (EITC).” National Conference of State Legislatures, 2017. Available at External Linkhttp://www.ncsl.org/research/labor-and-employment/earned-income-tax-credits-for-working-families.aspx

-

24

See IRS, “Statistics for 2016 Tax Returns With EITC.” Available at External Linkhttps://www.eitc.irs.gov/eitc-central/statistics-for-tax-returns-with-eitc/statistics-for-2016-tax-year-returns-with-eitc

-

25

See Andrew DePietro, “Here’s the No. 1 Thing Americans Do With Their Tax Refund,” GoBankingRates, 2017. Available at External Linkhttps://www.gobankingrates.com/personal-finance/thing-americans-tax-refund/ ; See also Tom Anderson, “Only 6 Percent of People Plan to Use their Tax Refund for Splurges this Year.” CNBC, 2017. Available at External Linkhttps://www.cnbc.com/2017/03/06/only-6-percent-of-people-plan-to-use-their-tax-refund-for-splurges-this-year.html