LMI Economic Conditions provides a detailed assessment of economic conditions in low- and moderate-income (LMI) communities, and each issue also provides insights into a special topic relevant to the LMI population. Much of the data used in the report come from a survey administered in the Tenth District, along with comments from that survey. In some areas of the report, national data are used and national conditions are considered. A person, household, or community is LMI if income is below 80 percent of area median income. For urban areas, area median income is metropolitan area median income. For non-metro areas, area median income is state median income.

I. Economic Update for LMI Communities

This issue of LMI Economic Conditions covers many aspects of economic conditions in LMI communities but places particular emphasis on labor market outcomes, which have been encouraging, and housing affordability, where conditions are challenging in many regards. Section I-A examines general perceptions of economic conditions in LMI communities and the demand for services from community organizations in the Tenth District. In Section I-B, I highlight labor market outcomes with a series of metrics and perceptions from the LMI Survey. These reveal some encouraging developments but also a continuation of comparatively poorer labor market outcomes when compared with other groups. The focus of Section I-C is housing affordability, where I provide survey information and supplemental data to address some continuing concerns in that sector. I analyze access to credit in Section I-D, where recent developments have been largely positive. Section II presents this issue’s special topic, which is a 10-year retrospective on the LMI Survey.

I-A. General Assessment

The most recent issue of LMI Economic Conditions reported a surge in the LMI Economic Conditions Index and suggested that a much higher value in the index could be a sign of economic activity stabilizing in LMI communities (all references to index values reflect assessments of conditions relative to one year ago unless stated otherwise) (see Box 1 for details on the calculation of the indexes). The report was cautiously optimistic, as a single data point is insufficient to make any definitive conclusions. Importantly, the LMI Economic Conditions Index is an indicator of changes in economic conditions in LMI communities, not the state of economic conditions. Respondents may have reported that conditions were improving but also believed them to be poor. Moreover, the encouraging outcome of the LMI Economic Conditions Index was tempered by the performance of some other indicators.

Diffusion Indexes

Survey participants respond to each survey question by indicating whether conditions during the current quarter were higher (better) than, lower (worse) than or about the same as in the previous quarter or year. Providers also are asked what they expect conditions to be in the next quarter. Diffusion indexes are computed by subtracting the percentage of survey participants that responded lower (worse) from the percentage that responded higher (better) and adding 100. The exception is the LMI Demand for Services Index, which is computed by subtracting the percentage of survey participants that responded higher from the percentage that responded lower and adding 100 so that higher needs translate into lower numbers for the index. A reading less than 100 indicates the overall assessment of respondents (balance of opinion) is that conditions are worsening. For example, an increase in the index from 70 to 85 would indicate conditions are still deteriorating, by consensus, but that fewer respondents are reporting worsening conditions. Any value more than 100 indicates improving conditions, even if the index has fallen from the previous quarter or year. A value of 100 is neutral.

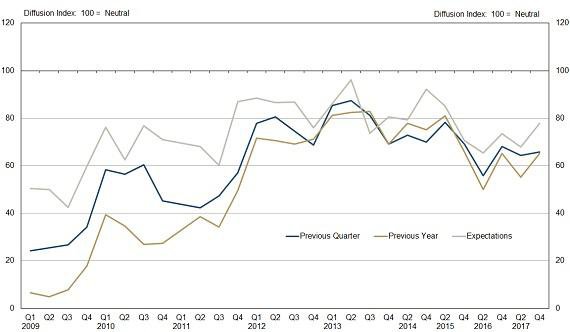

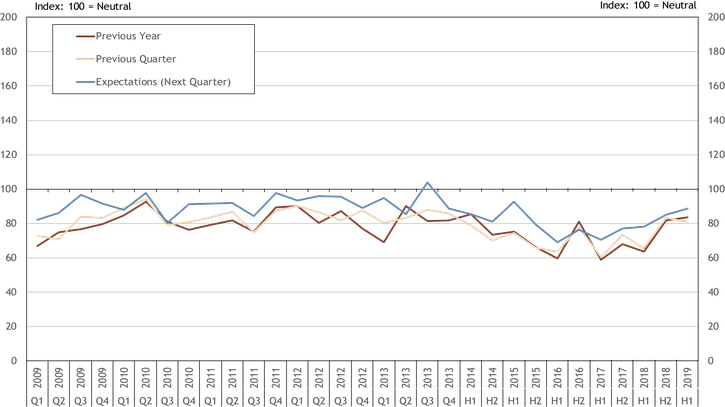

The overall assessment of LMI economic conditions was much the same in the July 2019 LMI Survey (hereafter July survey). While the LMI Economic Conditions Index fell to 87.3 from 93.1, it remained well above even its most recent values (Chart 1). In the three years preceding the January 2019 survey, the index ranged from 50.0 to 73.2. Thus, the index remained comparatively elevated in July, adding another data point to support the claim that economic conditions for the LMI population finally may be stabilizing. This assessment is bolstered by perceptions of economic conditions relative to the previous quarter (rather than year). The index of perceptions relative to the previous quarter advanced from 87.1 to 93.0 in July. Much like January, some results from the July survey and supplemental data temper this encouraging development.

Chart 1: LMI Economic Conditions Index

Although the balance of opinion is shifting upward, the LMI Economic Conditions Index still remained below neutral, meaning more respondents indicated conditions were deteriorating (32.4 percent) than reported they were improving (25.4 percent). The index also was modestly below neutral in January. Most survey comments pointing to worsening conditions mentioned wage growth relative to cost of living, particularly rent. Average rent has increased at annual rates of 3.4 percent to 3.9 percent in 2019, compared with overall price inflation of 1.5 percent to 2 percent; price increases for food (at home), however, have been tame over the past year relative to overall inflation._ As discussed in the following section, wage growth for lower-wage workers has been stronger than for other wage-earners and has been increasing. Of course, these are averages, and the financial circumstances of any one individual or household could be very different from the average individual or household. Some survey contacts also noted that political and policy uncertainties weighed adversely on their views of LMI economic conditions.

In addition, while the LMI Economic Conditions Index remained exceptionally high by historical standards, the LMI Demand for Services Index fell sharply from 51.4—already a low value compared with most LMI Survey indicators—to 40.5, its lowest value since 2012 (higher demand for services results in lower values for the index). The performance of the Demand for Services Index, which rarely has topped 50 over the 10-year history of the survey, seemingly is inconsistent with the strong performance of the LMI Job Availability Index (discussed in the next section) and recently improved LMI Economic Conditions Index. Survey comments were limited but pointed to higher rents and an aging population as some factors in the increased demand for services. Some survey contacts reported that adverse weather events increased demand for their services.

Interestingly, the LMI Economic Conditions Index has increased significantly (again, as measured by perceptions relative to the previous year) at a time when some signals indicate that national economic growth may be dampening. The labor market remains very tight, and household spending remains strong._ Nonetheless, investment has softened, and international developments such as trade conflicts and weaker economic growth internationally (as forecasted) could weigh on future growth._

Other indicators of economic conditions in LMI communities were largely flat. The LMI Job Availability Index remained strong, and the affordable housing index was able to modestly build upon its sharp increase in the January survey. The access to credit index dropped slightly but maintained its position close to neutral. Values for all indexes are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Diffusion Indexes for Low- And Moderate-Income Survey Responses

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City LMI Survey.

Notes: The diffusion indexes (see Box), were computed from responses to the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City’s biannual LMI Survey, conducted in July 2019. The survey asks respondents about conditions relative to the previous quarter and year as well as expectations for the next quarter.

I-B. Labor Market Conditions

Labor market conditions have been a bright spot in the economy for the LMI population and in LMI communities. Survey contacts continue to report that jobs increasingly are available for would-be LMI workers, and developments around wage growth are encouraging. On the other hand, there remain significant structural issues in the “LMI labor market.”

Labor Market Metrics

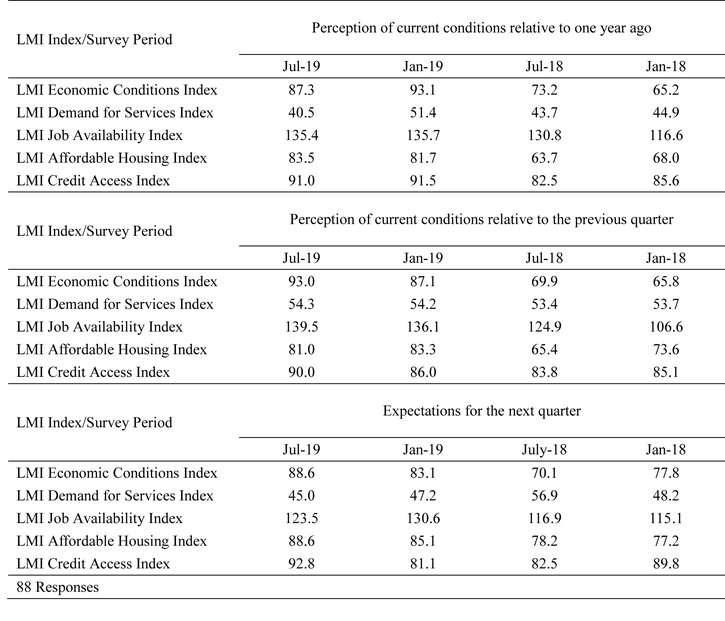

Each issue of LMI Economic Conditions includes a table of labor market metrics using non-survey data to supplement the survey data on labor market issues, which is necessarily limited in scope. These metrics can be compared over time and with other worker cohorts to help gauge strengths and weaknesses in the labor market faced by the LMI population (Table 2).

Table 2. Labor Market Metrics*

Unemployment rates remain historically very low for the nation. The U.S. unemployment rate was 3.7 percent in June (also in July), down from 4.0 percent a year prior. When the unemployment rate is low and employers have difficulty filling open positions, they may expand the pool of potential workers from which they hire. The expansion of these labor pools to formerly disconnected, more diverse populations can be especially helpful for LMI job-seekers. For example, evidence suggests employers increasingly are hiring disabled individuals who may have been overlooked in looser labor markets._ LMI communities have much larger population shares with disabilities than non-LMI communities. In the latest available data, 14.6 percent of the 18-64 population had a disability in LMI census tracts, compared with 9.9 percent in non-LMI census tracts._ In 2018, 8 percent of the disabled were unemployed, down from 9.2 percent in 2017, and the labor force participation rate for the disabled edged up from 20.6 percent to 20.8 percent._ Companies also are more willing to hire ex-offenders, which is a high hurdle for a significant number of LMI individuals wanting to work._ Evidence from LMI Survey comments and focus group discussions with non-working LMI individuals suggests that criminal convictions are a much more significant barrier to work for job-seekers in LMI communities than in higher-income communities._

For working-age individuals in LMI households, the unemployment rate was much higher than the national rate at 8.1 percent in June 2019, down moderately from 8.5 percent in June 2018. The labor force participation rate for working-age individuals in LMI households, which is the share either working or actively seeking work, is considerably lower (44.6 percent in June 2019) than for the working age population as a whole (62.9 percent).

Beginning with the January 2019 issue, the labor market metrics were expanded to include more complete statistics by education, race and ethnicity. The LMI population is disproportionately less educated and minority. As expected, those with less formal education, as a group, have higher unemployment rates and much lower rates of labor force participation. The statistics for minorities are consistent with persistently higher unemployment rates for most minority groups. Differences in labor force participation are not as pronounced, although Hispanic/Latino individuals of working age have moderately higher rates of labor force participation. Labor force participation rates for those with less than a high school education were similar to those calculated for working-age adults in LMI households.

Evidence from the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey shows that labor market outcomes typically also are poorer not only in LMI households, but also in LMI communities as a whole. Using averages for 2013-17, the latest date for which data are available at the census tract level, the employment rate (share of population that is working) for those 18-64 was only 65 percent in LMI census tracts, compared with 75.1 percent in non-LMI census tracts. Higher rates of unemployment (9.1 percent vs. 5.1 percent) and labor force nonparticipation (28.1 percent vs. 20.5 percent) contributed to this difference.

LMI Job Availability Index

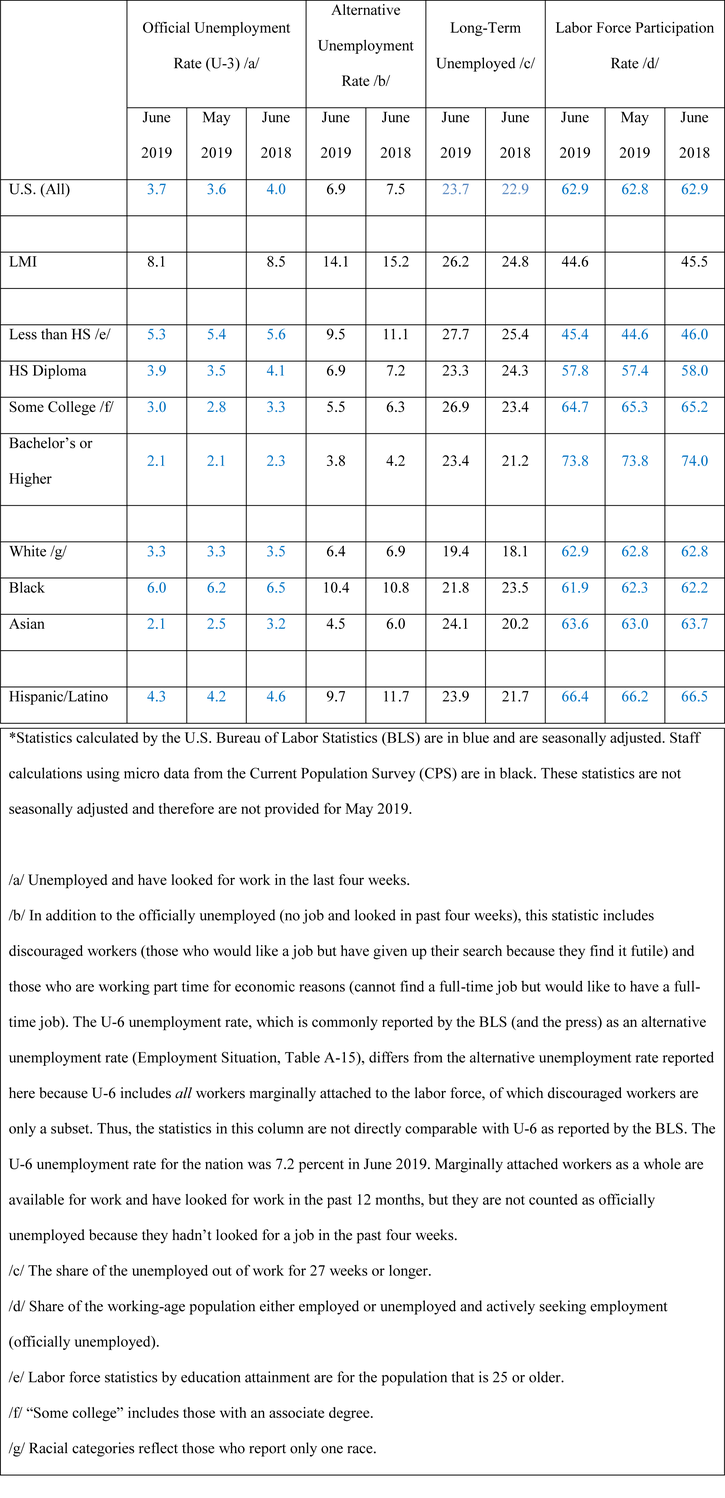

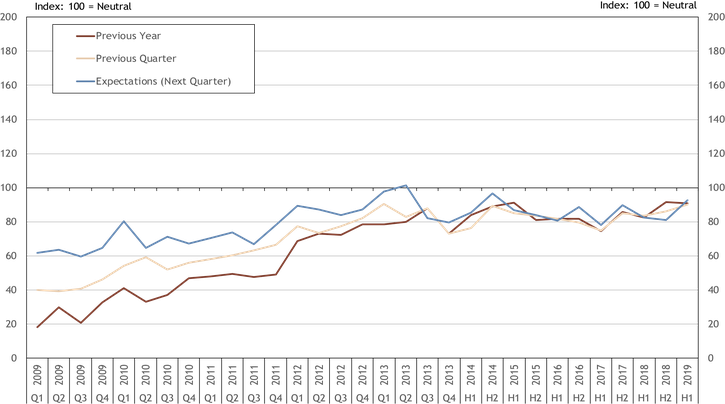

LMI Survey responses on job availability are consistent with the strength in current labor market statistics. The LMI Job Availability Index was roughly flat in the July survey, dipping slightly to 135.4 from 135.7, but remained near its January peak (Chart 2). Perceptions relative to the previous quarter achieved a new peak, rising from 136.1 to 139.5. The index of expectations for the following quarter declined to 123.5 from 130.6 but remained well above neutral, indicating that continued increases in job availability for LMI job-seekers are expected. Almost half of survey respondents reported jobs were more available compared with the previous year (45.7 percent), while only 6.2 percent responded that jobs were less available (the remainder reported no change). Overall, the LMI Job Availability Indexes reflect significant optimism for labor markets among organizations that support the LMI population and LMI communities.

Chart 2: LMI Job Availability Index

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City LMI Survey; staff calculations.

Note: The survey asks respondents to assess conditions relative to the same period in the previous year, conditions relative to the previous quarter, and for their expectations for the following quarter relative to the current quarter.

Survey comments were largely upbeat, considering the availability of jobs specifically, but on the flip side, shortages of workers can be a problem. Many survey contacts suggested the number of job-seekers is insufficient to meet the hiring needs in their communities. Indeed, comments on labor shortages were pervasive. Significant shortages exist where there are openings for relatively low-skill, low-pay positions. Survey comments suggest that potential hires often are reluctant to take jobs with earnings that would leave them “unable to make ends meet.” Unsurprisingly, there was regional variation in the comments. Contacts from energy-intensive parts of the District were decidedly downbeat about the local labor market. Some contacts in areas with significant seasonal employment reported that high housing costs were limiting the ability of local businesses to make hires or for job-seekers to take advantage of seasonal opportunities.

Much of the negativity in comments on job availability, which has been limited, relate to low earnings, especially as related to the costs of supporting one’s self or family. Fortunately, wage data suggest that LMI workers are making gains. The largest wage gains recently have been in relatively low-paying occupations. Wages in the bottom quartile of the wage distribution have averaged annual growth of 4.3 percent in the last 12 months, compared with overall annual wage growth of 3.4 percent._

I-C. Housing Affordability

The LMI Housing Affordability Index increased from 81.7 to 83.5 in the July survey (Chart 3). This moderate gain followed a surge in the January survey from 65.4. Although the index is trending upward, it has not fully recovered from its slide between 2013 and 2016, a period of especially rapid growth in rents. Moreover, while the index has increased measurably, it remains below neutral, meaning that the balance of opinion among survey contacts is that affordable housing is becoming less available.

Chart 3. LMI Affordable Housing Index

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City LMI Survey; staff calculations.

Note: The survey asks respondents to assess conditions relative to the same period in the previous year, conditions relative to the previous quarter, and for their expectations for the following quarter relative to the current quarter.

Despite gains in the index, survey comments were overwhelmingly downbeat. There were multiple reports of formerly affordable housing being converted to market-rate housing. One respondent in one of the District’s largest counties reported a decline of over 20 percent in the number of apartment complexes in the county that would accept Section 8 voucher tenants. There were some reports of additional affordable housing coming on line in some communities, but these were few in number. Some contacts highlighted the instability that lack of access to affordable housing can bring, such as children facing difficulties at school and more challenges acquiring and retaining employment.

Those seeking market-priced rental units with more modest rents also may face difficulty finding available housing. Supply-side factors have constrained multifamily construction, and vacancy rates are low compared with historical benchmarks, with the exception of centrally located luxury units in some metropolitan areas._ Some LMI Survey comments criticized the pursuit of high-value projects by developers over projects that would provide more affordable units—a common refrain in recent surveys.

Those seeking to purchase lower-priced homes may not fare much better. A recent report by Redfin shows that homes in the lowest-priced tier (bottom tercile by average sales price) have seen the greatest price increases: 8.7 percent year-over-year to June 2019, compared with only 1.1 percent for homes in the highest-priced tier._ The report noted that price growth in the lowest price tier remained solid even when house price growth cooled in late 2018 and early 2019. It further noted that annual price growth in the lowest price tier has not fallen below 4.5 percent in at least seven years.

I-D. Access to Credit

The LMI Credit Access Index largely held steady in the July survey following a sizeable increase in January. The index dipped to 91.0 from 91.5. The January value was the peak for the index over the LMI Survey’s 10-year history. The index has marched gradually toward neutral over the past two years following a moderate downturn in the previous two years (Chart 4). The near-neutral value in the index in the July survey reflects mostly reports of no change in credit conditions, which accounted for two-thirds of responses.

July survey comments on access to credit overall were surprisingly positive. The general tenor of comments in past surveys on access to credit have been highly pessimistic. Also unusual was a lack of criticism of alternative financial institutions in the July survey, although survey respondents’ views on alternative financial products such as payday loans is unlikely to have changed appreciably. Positive developments reported by survey contacts included an increased availability of funds for those wanting to start businesses and expanded financial services being made available to LMI consumers. However, some contacts who reported increased access to credit suggested that many of these credit resources were not affordable.

Chart 4: LMI Credit Access Index

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City LMI Survey; staff calculations.

Note: The survey asks respondents to assess conditions relative to the same period in the previous year, conditions relative to the previous quarter, and for their expectations for the following quarter relative to the current quarter.

Summary

LMI Survey indicators continue to point to potential recovery, even as the national economy shows signs of moderate softening. But while the LMI Economic Conditions Index remained exceptionally high by historical standards, the LMI Demand for Services Index fell sharply and remains substantially below neutral, indicating increased demand for services. The labor market faced by the LMI population is solid, although the health of the LMI labor market has been persistently short of those in higher-income cohorts. The most significant weakness in LMI economic conditions seems to be an insufficient supply of affordable housing. Survey comments on access to credit were more upbeat than in most previous surveys, largely reflecting increased access to credit.

II. In This Issue: 10 Years of the LMI Survey

The LMI Survey, which serves as the primary input in LMI Economic Conditions, started in early 2009. This year represents the 10-year anniversary, providing an opportunity to evaluate the survey. After briefly discussing the survey’s background and use, I analyze the survey’s performance in terms of its consistency with related external data, the degree to which current values of the quarter-over-quarter LMI diffusion indexes are similar to their previous quarter’s projections, and the correlation between the headline LMI Economic Conditions Index and the business cycle.

II-A. Background

The impetus for the LMI Survey was a need for data specific to the LMI population. Prior to starting the survey, the Kansas City Fed sought to package and analyze existing data on the LMI population and LMI communities. However, we learned there was very little relevant data. The lack of existing data was the motivation for creating the survey.

Survey respondents are organizations that engage directly with the LMI population on a regular basis._ These organizations serve as proxies for LMI individuals themselves, for whom a regular survey would be intractable for many reasons._

Responses to both the point-and-click objective questions in the survey and the text comments provide significant value. The greatest value in the objective responses is that they can be used to create informative indexes that can be tracked over time. For example, the LMI Job Availability Index revealed that employment recovery in LMI communities lagged recovery in national employment by about two years but in recent quarters has been very strong. As an additional example, both the LMI Economic Conditions and LMI Demand for Services Indexes consistently have pointed to economic deterioration. This inconsistency led us to host focus groups to dig more deeply into why so many organizations continue to see poorer conditions despite a robust national economy._ Survey comments provide context for the indexes. We also ask special questions to gain more insight into areas of deeper concern.

Results from the LMI Survey have been used many ways. The primary purpose of the survey is to inform both ourselves and our stakeholders. The information is distributed primary through this report, and formerly, the LMI Survey Report. Within the Kansas City Fed, survey results assist in strategic decision-making for our community development function. In addition, data from the LMI Survey have been used in formal research projects._

II-B. Evaluation of the Survey

I examine consistency of conditions measured from the survey with other data that are relevant to the LMI population (construct validity), how respondents’ quarter-ahead forecasts compare with next quarter outcomes and if LMI Survey indexes are correlated with other economic outcomes.

Construct Validity

Survey “validity” is considered essential to a high-quality survey._ Of particular importance is construct validity, which means the survey results accurately reflect the latent concept the survey seeks to measure. In the case of the LMI Job Availability Index, for example, construct validity would mean the index truly measures the quantity of jobs available to LMI job-seekers. There is no precise quantitative measure of construct validity, which is a very complex concept._ However, survey results can be compared with related empirical findings as a prerequisite for construct validity.

One way to assess the construct validity of the LMI Job Availability Index, by this standard, is to compare the index against employment growth in jobs LMI workers are most likely to seek. LMI workers are presumed to work mostly low-skill jobs, which I define here as jobs that do not require a formal education credential or significant work experience._ Two industries that typically offer jobs with these criteria are accommodations and food services and retail. In previous research, I find the LMI Job Availably Index to be highly correlated with annual employment growth in retail sales occupations (r= 0.77) and occupations in the accommodations and food services industry (r = 0.86)._ I further demonstrate that other LMI Survey results also are consistent with empirical findings. I find significant correlations between the LMI Affordable Housing Index and Fair Market Rent (r = ‒0.71) and between the LMI Credit Access Index and (a) various interest rates (r = ‒0.91 for four-year-old used car at $9,000; r = ‒0.71 for unsecured loan of $1,000; and r = 0.87 for 30-year $175,000 fixed-rate mortgage), as well as (b) lending standards, where a higher number means tighter credit standards (r = ‒0.82)._

Expectations

An interesting and useful exercise is to judge how well survey contacts’ expectations match their perceptions in the succeeding period. This analysis can help determine the value of these expectations in assessing conditions going forward. For each set of survey questions, respondents are asked for their perceptions relative to the previous quarter and previous year, but also their expectations for the following quarter. For each of the five sets of questions related to economic conditions in LMI communities, I use a statistical analysis to judge the correlation between expectations and survey outcomes in the following quarter.

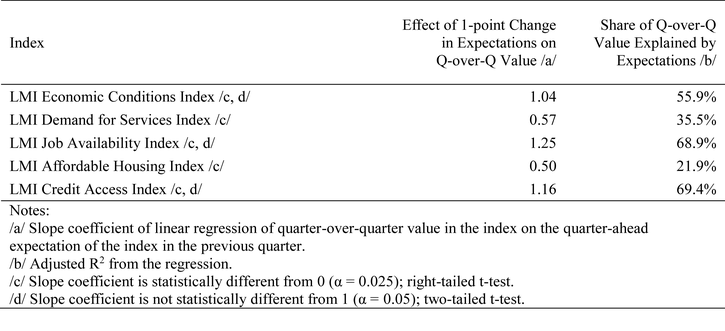

The results from the statistical analysis suggest that survey respondents generally do well in anticipating conditions in the next quarter. For all indexes, a higher (lower) value for expectations in the next quarter is associated with a higher (lower) value in the quarter-over-quarter index in the following period and all are statistically greater than zero (Table 3). Predictions for the LMI Economic Conditions Index are particularly prescient. A 1-point higher value in the index of expectations is associated with a 1.04 higher value in the quarter-over-quarter index in the succeeding quarter. As would be expected, this parameter is not statistically different from 1. The equivalent parameters for the LMI Job Availability and LMI Credit Access Indexes also are not statistically different from 1, meaning that the estimated values are close enough to 1 that the statistical procedure cannot rule out that the true values are 1. If the true values were 1, the change in the current quarter’s value would be identical to the change in expectation for that value in the previous quarter.

Table 3. Quarter-over-Quarter Value and Quarter-Ahead Expectations from the Previous Quarter

Association with Other Economic Indicators

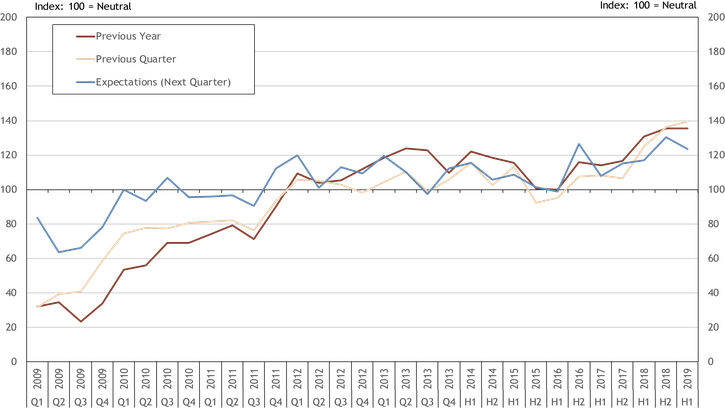

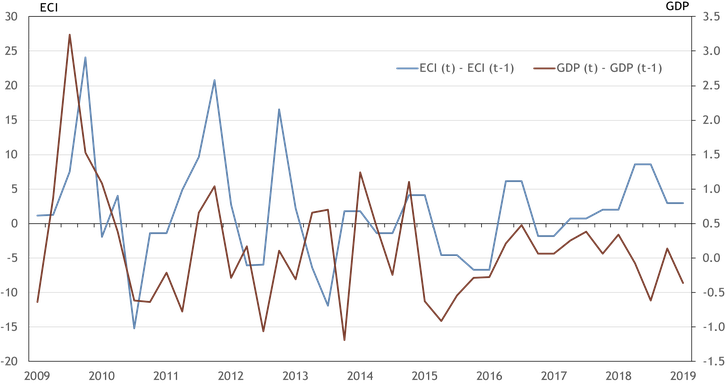

As a final evaluation of the LMI Survey results, I analyze the co-movement of the LMI Economic Conditions Index (ECI) with the business cycle, as measured by growth in gross domestic product (GDP). I compare annual growth in GDP (gGDP) with the ECI (conditions relative to one year ago) using a statistical model._ To properly estimate the model, I must “first-difference” both gGDP and ECI (that is, I must subtract the previous value from the current value, denoted ∆gGDP and ∆ECI). Chart 5 shows first-differences in gGDP and ECI over time, which visually appear to be correlated. The statistical analysis bears that out. Specifically, a 3-point increase in the LMI Economic Conditions Index is associated with a 0.1 percentage point higher annualized rate of GDP growth in the following quarter._

Chart 5: LMI Economic Conditions Index (ECI) and Growth in GDP (in first-differences)

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City LMI Survey; U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis/Haver Analytics; staff calculations

Notes: First and third quarter values for the LMI Economic Conditions Index were estimated for 2015-19.

Summary

The LMI Survey has proven to be a useful tool for assessing economic conditions in LMI communities, especially in the absence of alternative data. It provides significant value in informing both the Kansas City Fed and our stakeholders and has been useful in planning how to best to use our limited community development resources. An evaluation of the survey over the past 10 years suggests that 1) LMI Survey indicators are positively correlated with other economic conditions relevant to the LMI population and LMI communities, 2) respondents’ expectations are correlated with the following quarter’s survey outcomes, and 3) past values of the headline LMI Economic Conditions Index are correlated with broader economic phenomena.

Endnotes

-

1

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Consumer Price Index for all urban consumers (U.S. city average), “All Items,” “Rent of Primary Residence” and “Food at Home”/Haver Analytics.

-

2

Increased wage growth and a strong rebound in consumer confidence in July likely contributed to solid household spending. Wage growth is discussed in the following section. The Conference Board’s Consumer Confidence Index increased from 124.3 in June to 135.7 in July.

-

3

See, for example, the External Linktranscript of Federal Reserve Chairman Powell’s post-FOMC press conference, July 31, 2019.

-

4

Accenture, 2019, “External LinkGetting to Equal: The Disability Inclusion Advantage.” At least in some cases, companies have found these more inclusive hiring to improve the bottom line.

-

5

U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey, 2017 5-Year Averages, Table DP02.

-

6

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “External LinkPersons with a Disability 2018,” Feb. 26 2019.

-

7

Thomas Ahearn, Dec. 21 2018, “External LinkLow Unemployment Makes Employers More Willing to Hire Ex-Offenders with Criminal Records in 2019” Employment Screening Resources; Ben Casselman, Jan. 13 2018, “Jailed, Shunned, But Now Hired In Tight Market,” The New York Times, Section A, Page 1. (retitled online: “External LinkAs Labor Pool Shrinks, Prison Time Is Less of a Hiring Hurdle”).

-

8

Numerous comments in a 2017 special question in the LMI Survey on barriers to employment asserted that criminal records are a significant factor keeping LMI individuals out of work. This problem also has been voiced in many other LMI Survey comments, both related to labor market issues specifically and in general comments. In focus groups hosted in spring 2019 by the Federal Reserve Banks of Kansas City and Chicago, the problem of finding work with a criminal conviction was one of the most prevalent issues identified by non-working LMI adults. Transcripts from these focus groups are being processed for further analysis.

-

9

Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta, External LinkWage Growth Tracker.

-

10

Jordan Rappaport, June 5, 2019, “Escaping the Housing Shortage,” Economic Bulletin, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City.

-

11

Dana Olsen, July 23, 2019, “External LinkPrices for the Most Affordable U.S. Homes Up 9% in June,” Redfin. This analysis relies on median sales prices, which could be a problem if alternate periods’ sales were to skew to different price groups (such as entry-level homes). The comparison of median sales prices over time also ignores changes in average quality of the housing stock over time. A benefit is a large number of transactions can be used in the analysis. Repeat-sales indexes might be preferable given the problems highlighted with using median sales prices, but many fewer transactions are available for analysis. See Jordan Rappaport, 2007, “A Guide to Aggregate House Price Measures,” Economic Review, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, vol. 92, no. 2, pp. 41-71 or Jordan Rappaport, 2007, “External LinkComparing Aggregate Housing Price Measures,” Business Economics, vol. 42, no. 4, pp. 55-65.

-

12

Readers who regularly engage the LMI population are encouraged to participate in the LMI Survey.

-

13

Common problems surveying low-income populations are discussed in Kelly D. Edmiston, 2018, “Reaching the Hard to Reach with Intermediaries: The Kansas City Fed’s LMI Survey,” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City Research Working Paper 18-06, July.

-

14

The Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago, which has seen similar survey results, also is participating in this project.

-

15

Relying in large part on LMI Survey indexes, “The Low- and Moderate-Income Population in Recession and Recovery” evaluates the economic circumstances of the LMI population over the course of the Great Recession and early recovery (Kelly D. Edmiston, 2013, Economic Review, Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, vol. 98, no. 3, pp. 33-57). Ongoing research includes a study of barriers to employment in LMI communities, which employs a formal text analysis of LMI Survey comments, and a study of economic perceptions among the LMI population and community development organizations, which is largely based on focus group material informed by LMI Survey results.

-

16

Duane F. Alwin, 2010, “How Good is Survey Measurement? Assessing the Reliability and Validity of Survey Measures,” in Peter V. Marsden and James D. Wright (eds.), External LinkHandbook of Survey Research (UK: Emerald).

-

17

Lee Sechrest, 2005, “External LinkValidity of Measures Is No Simple Matter,” Health Services Research, vol. 40, no. 5 (Part 2), pp. 1584-1604.

-

18

Information on job requirements is from in the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, External LinkOccupational Outlook Handbook.

-

19

Edmiston, op. cit. The expression “r” refers to the Pearson correlation coefficient when applied to sample data. The coefficient measures the linear correlation between two variables and ranges between ‒1 (perfectly negatively correlated) and +1 (perfectly positively correlated). Data on External Linkoccupational employment are from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics/Haver Analytics.

-

20

Fair Market Rent is calculated for local areas annually by the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development for use in setting payment standard amounts for the Housing Choice Voucher program (Section 8). Data on lending standards are from the Federal Reserve’s External LinkSenior Loan Officer Opinion Survey on Bank Lending Practices/Haver Analytics. Data on interest rates are from External LinkRATEWATCH.

-

21

Thus, for July 2019, gGDP = [(GDPJuly 2019/GDPJuly 2018) - 1] x 100 which is the percentage change in GDP over the year. I do the same calculation for gGDP for other quarters. As noted in the text, ECI represents survey respondents’ perceptions of economic conditions compared with one year ago.

-

22

I estimate a transfer function where ΔgGDP is ARIMA (0,1,1). The estimated model is , where "t" indicates a quarter. The standard error for ΔECIt-1, is 0.017. The associated significance tests are t =0.333/0.172 = 1.94 and p = 0.062. I also estimated a simple vector auto regression (VAR) where ΔgGDP (t ) = β0 + β11ΔgGDP (t - 1) + β12ΔgGDP (t - 2) + β21ΔECI (t - 1) + β22ΔECI (t - 2) and ΔECI (t) = α0 + α11 ΔECI (t - 1) + α11 ΔECI (t - 2) + α21ΔgGDP (t - 1) + α22ΔgGDP (t - 2). None of the coefficients were statistically significant in the VAR. This result does not necessarily mean that these lags do not matter, especially in this context where there are few observations relative to parameters. In these cases, it is very unlikely to detect effects with reasonable statistical power. Details about these procedures are available in many textbooks. I believe one of the most straight-forward guides to this type of analysis is Walter Enders, 2004, Applied Econometric Time Series, Second Edition (Wiley). A Fourth Edition is available.