General Assessment

Indicators of economic and financial conditions in the LMI community were computed from results of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City’s biannual LMI Survey, which was administered in January 2016 (“January survey”) (the survey is biannual, but asks respondents about conditions in the previous quarter and year, as well as projections for the current quarter).1

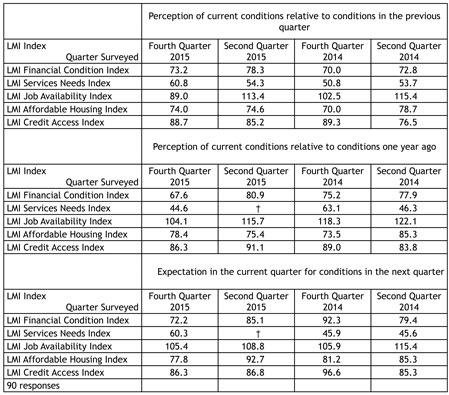

These indicators suggest at least a temporary slowdown in the recovery in the LMI economy, although results from a single survey are not sufficient to establish a trend. In comparison to the previous survey (“July survey”), most indicators fell, with significant drops in the job availability index and year-over-year general financial condition index, while the demand for services index remained subdued (unless otherwise specified, index numbers refer to an assessment of conditions relative to the previous quarter). Historically, most survey indexes persistently have fallen below the neutral level of 100, indicating at least mild deterioration. Index values themselves, however, have trended upward (see box).

LMI individuals (or families or households) are those with incomes less than 80 percent of area median income. For those in urban areas, area median income is the value for the metropolitan area; for those in rural areas, it is state median income.

Diffusion Indexes Providers of services to the LMI population respond to each LMI Survey question by indicating whether conditions during the current quarter were “higher” (or “better”) than, “lower” (or “worse”) than, or the same as in the previous quarter or year. Diffusion index numbers are computed by subtracting the percent of service providers that responded “lower” (or “worse”) from the percent of service providers that responded “higher” (or “better”) and adding 100. The exception is the LMI Services Needs Index, which is computed by subtracting the percent of service providers that responded “higher” from the percent of service providers that responded “lower” and adding 100 to show that higher needs translate into lower numbers for the index. Any number below 100 indicates the overall assessment of survey respondents is that conditions are worsening. For example, an increase in the index from 70 to 85 would indicate conditions are still deteriorating, by consensus, but that fewer respondents are reporting worsening conditions. Any value above 100 indicates improving conditions, even if the index has fallen from the previous quarter or year. A value of 100 is neutral. In the case of the LMI Financial Condition Index, a larger share of respondents (33.8 percent) reported that conditions had worsened than reported that they had improved (7 percent) in the January survey, leading to the consensus reading below neutral (7-33.8+100=73.2).

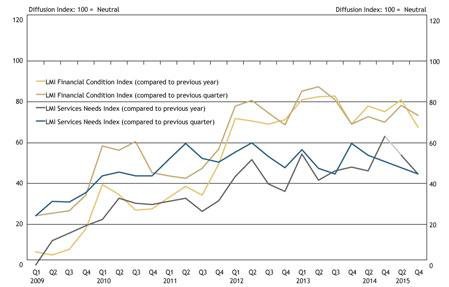

The LMI Financial Condition Index, the broadest assessment of economic conditions in the LMI community, fell moderately from 78.3 in the July survey to 73.2 in the January survey (Chart 1); however the comparable index that reflects assessments of conditions relative to one year ago fell more significantly, from 80.9 to 67.6, indicating that, compared to the previous survey, more respondents reported that economic conditions had deteriorated over the last year. Both indexes of financial conditions remain significantly below a neutral reading of 100, indicating persistent deterioration in general economic conditions in the LMI community. Respondents’ assessment of the LMI labor market, which was downbeat relative to the previous survey, likely was the chief factor affecting this general appraisal of LMI economic conditions, as movement in other indicators generally was more modest, and labor market outcomes are critical to the economic condition of individuals and their families.

Chart 1: LMI Financial Condition Index and LMI Services Needs Index

Note: LMI Survey data were collected quarterly prior to 2014. For details on the computation of diffusion index values, see box inset in the text. (Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City LMI Survey)

The Demand for Social and Community Services

Another broad indicator of LMI economic conditions is the LMI Services Needs Index, which rose moderately from 54.3 in the July survey to 60.8 in the January survey (Chart 1). The index reflects the demand for services provided by organizations responding to the survey. An increase in demand for these services is associated with deterioration in economic conditions, and, by construction, a decline in the index (see box). The results imply many contacts continue to report greater demand for their services, but fewer than in the previous survey. As the most objective question in the survey, the pattern in this index complements the much more subjective poll of assessments of financial well-being reflected in the LMI Financial Condition Index.

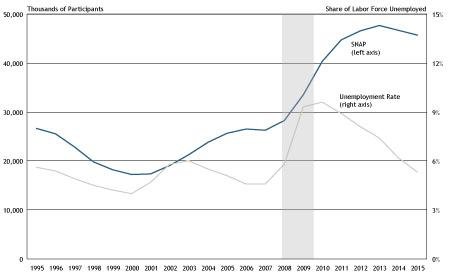

External data, at least through 2014, largely support the assessment of community organizations responding to the LMI Survey. Although participation in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), formerly known as food stamps, has declined about 2 percent in the last two years, it continued to increase well after the Great Recession officially ended and employment began to grow steadily (Chart 2).

Chart 2: Participants in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP)

(Sources: U.S. Department of Agriculture; U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics)

The 2007-09 recession was marked by historically high levels of long-term unemployment, traditionally defined as more than 26 weeks. Unemployment beyond one year also was exceptionally high by historical standards (see “Labor Market” below). Workers unemployed for long periods often deplete any available savings, then tap retirement funds and utilize credit. Support from family and friends often is exhausted quickly.2 As the duration of employment increases for an individual or family, the likelihood of fully depleting personal resources and turning to social services and other community services increases. Responses in a number of past LMI Surveys noted an influx of “formerly middle-class” individuals and families seeking support and services well after the end of the recession, suggesting that depletion of personal resources after unemployment was the critical factor.

A special question in the January survey sought respondents’ insight on why the demand for services has increased unabated (the index has remained well below neutral) while other indicators of economic conditions in LMI communities have improved, with some making significant progress toward neutral or even breaching that line.

In addition to the dim assessment of quarter-over-quarter job availability in the January survey (discussed below), many respondents to the special question reported that where jobs are available for LMI workers, wages are stagnant at best, and many have taken jobs at lower pay and/or reduced hours. Respondents indicated these low incomes often are insufficient to meet basic needs, such as housing, utilities, food, medical care and transportation. A significant number indicated price inflation in these goods and services is outpacing gains in wages and income.

A significant majority of responses to the special question highlighted increased rents or other housing costs as a major factor explaining the continued increase in demand for social and community services, especially respondents from Colorado, most of whom cover the Denver metropolitan area.3 A more extensive analysis of housing issues is discussed below.

Finally, economic conditions are uneven across the Tenth District. The New Mexico economy continues to struggle in its recovery relative to other District states while Oklahoma and Wyoming are coping with a sizeable contraction in the energy industry. Responses to the special question also reflected these realities.

Healthcare and the Affordable Care Act

With a Jan. 31 enrollment deadline looming for obtaining health insurance under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), respondents to the January LMI Survey were asked for their impressions of progress in the implementation of the associated laws and regulations. Responses about enrollment rates, affordability and general understanding of the ACA process varied widely by state.

A number of respondents reported a significant increase in the share of their clients who have health insurance and attributed that to the ACA. However, an equivalent number reported significant challenges with the health insurance exchanges—mostly confusion among enrollees and difficulties completing the enrollment process. In these cases, many contacts expressed a plea to policymakers to simplify the process. A majority of responses to the special question suggested many of their clients cannot afford health insurance through the exchanges, even with subsidies. The comments reflected the fear among some contacts that the gap between affording health insurance and qualifying for significant subsidies, particularly through Medicaid, may leave some LMI individuals and families to “fall through the cracks.”

Labor Market

Labor market conditions typically are the primary driver of overall evaluations of economic conditions. Indicators of labor market conditions typically have been the strongest in the LMI Survey, but results from the January survey raise some concerns. However, other labor market indicators from the survey and analyses of external data support a judgment of relative strength in the LMI labor market and that present concerns may be short-lived.

Survey Results

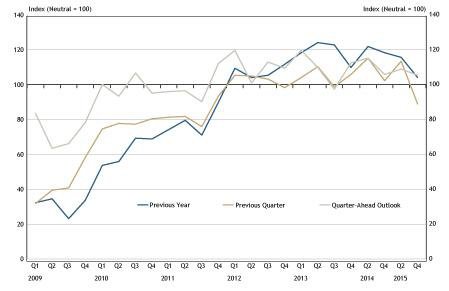

Results from the LMI Survey’s inquiry on the availability of jobs for LMI workers in the Tenth District dropped sharply in the January survey, falling more than 24 points to 89, about where it stood in the fourth quarter of 2011 (Chart 3).4 Nevertheless, the assessment of job availability relative to the previous year and the outlook for the next three months remained above neutral, tempering concerns.

Survey respondents’ assessment of quarter-over-quarter job availability is in marked contrast to national employment growth of 851,000 jobs over the same period, an average of about 284,000 net new jobs per month, which is high by historical standards.5 Most respondents to the LMI Survey reported no change in LMI labor market conditions, but the number reporting a decline in job availability was larger than that reporting increased job availability, leading to a reading below neutral for the job availability index.

The energy sector has a relatively large presence in the Tenth District, and recent contraction in that sector arising from lower commodity prices likely contributed significantly to quarter-over-quarter assessments of job availability. Indeed, half of all survey contacts responding “worse” were from Oklahoma and Wyoming, which account for less than one-quarter of District population and much of its oil and gas industry.6

Oklahoma and Wyoming respondents also accounted for disproportionate shares of negative responses in other survey questions. The latest (Jan. 8, 2016) issue of the Tenth District Energy Survey shows that more than half of energy firms surveyed reported declines in employment of 10 percent or more in 2015.7

In areas dominated by the energy industry or other resource-extracting industries, labor demand by extractive industries may crowd out manufacturing or other sectors, leading to a local economy highly dependent on a sector known for cycles of booms and busts. In particular, labor demand by the extraction industry may push up wages and draw workers from other, lower-paying jobs, creating an economy that is less diversified and less resistant to shocks generated by lower commodity prices.8

Research is fairly extensive on this phenomenon, often called a “resource curse,” but much less research has evaluated the reverse case, where activity in extractive industries has declined significantly, and outcomes may be asymmetric. Recent Kansas City Fed research, however, has shown there were significant declines—about 2 percent—in total employment in Oklahoma following previous energy “busts” and that these employment declines resulted in part from spillovers into other sectors.9 Thus, losses in employment and income might be expected to bleed into other sectors that are more likely to employ LMI workers.

Survey respondents identified many difficult challenges LMI workers face outside of overall economic activity. Chief among these were a lack of education, training and experience sufficient to advance workers in the current labor market, health issues, transportation and child care.

Chart 3: LMI Job Availability Index

Notes: LMI Survey data were collected quarterly prior to 2014. For details on the computation of diffusion index values, see box inset in the text. (Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City LMI Survey)

Analysis of External Data

The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) releases a number of alternative unemployment and underemployment statistics in addition to the commonly reported “headline” unemployment rate, currently 4.9 percent for the nation. Most of the alternative measures of labor utilization are released only for the entire United States and individual states (data are released on a quarterly basis for states).10 Thus, one cannot readily locate similar data for defined income classes; educational attainment cohorts; occupational classes; or consolidated districts, such as the Tenth District. For this report, individual household data from the Current Population Survey (CPS) are used to calculate these statistics for Tenth District states.11

Unemployment

The official U.S. unemployment rate published by the BLS, known as U-3, was 4.9 percent in January, on a seasonally adjusted basis, down from 5.0 percent in October-December 2015 and 5.7 percent in January 2015. The Tenth District unemployment rate in December 2015 (latest available) was 4.1 percent.12 This rate is the share of the labor force that is not currently working but actively seeking employment.

LMI Breakdown of Unemployment

Unemployment rates by income group are not reported in government statistics, and disentangling unemployment and income is difficult. For example, an unemployed worker is likely to have little or no income, and those in low-income families are more likely to be unemployed.13 Some insights are provided by more narrow statistics that can be related to characteristics typical of LMI workers, such as educational attainment. Specifically, unemployment is highly correlated with educational attainment, and LMI workers typically are less educated than higher-income workers.14 In the most recent statistics, the U.S. unemployment rate of those with a bachelor’s degree was 2.4 percent, compared to 4.5 percent for those with a high school diploma, but no college.15 The unemployment rate for those who had not completed high school was 7.6 percent.

Duration of Unemployment

A key problem among the unemployed is the long-term unemployed. The labor market circumstances faced by the long-term unemployed, who the BLS define as unemployed for more than 26 weeks, typically are more dire than those faced by the short-term unemployed. The long-term unemployed are more likely to have reached state or federal limits on unemployment compensation or had extended benefits programs nullified because of improvements in labor market conditions. As noted in the previous section, they also are much more likely to have exhausted their personal resources, such as precautionary savings, retirement accounts and credit.

In addition, the long-term unemployed typically have greater difficulty securing a new job. Skills may atrophy or become obsolete over time. Employers recognize this potential, which may make them more reluctant to hire the long-term unemployed. Employers also may question why after an extended time a worker has not secured another job when others have.

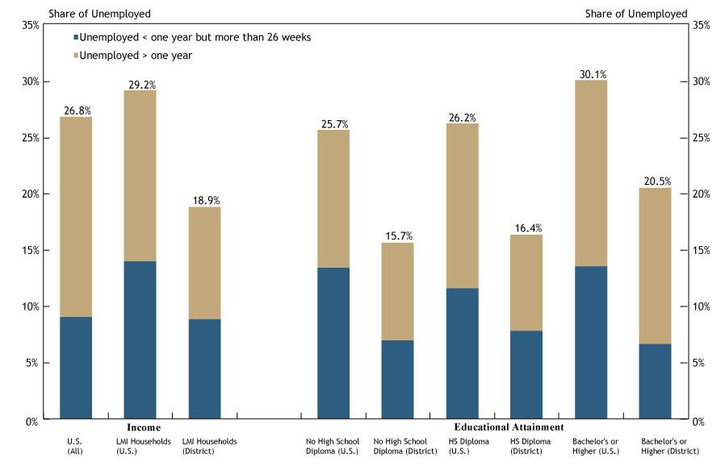

Long-term unemployment accounted for about 29 percent of all U.S. unemployed workers living in LMI households in December 2015, and just less than 19 percent of unemployed workers in LMI households in the District (Chart 4).16 About 27 percent of all unemployed workers in the United States are long-term unemployed. These figures, while high from a historical perspective, have improved significantly over a relatively short period. From a longer-run perspective, from post-World War II to pre-recession in 2007, the long-term unemployed share of total unemployment had never exceeded 25 percent annually for the nation.17 More than 40 percent of the unemployed, however, were long-term unemployed at the trough of the recent “employment recession” in 2010-11.

Compared to the United States, the District’s long-term unemployment rate is much lower, consistent with its much lower “headline” unemployment rate of 4.1 percent in December (seasonally adjusted).18 The rate of long-term unemployment is highly correlated with the overall unemployment rate: the higher the unemployment rate, the higher the long-term unemployment rate tends to be.19 Long-term shares of unemployment by educational attainment vary little.

Marginally Attached Workers

Beyond the official unemployment rate is a shadow group of individuals who are not officially unemployed, but are “marginally attached” to the labor force. Persons “marginally attached” to the labor force want and are available for work and have looked for a job sometime in the prior 12 months (or since the end of their last job if they had one within the past 12 months), but are not counted as unemployed because they have not searched for work in the four weeks preceding the BLS survey. For this report, the marginally attached are analyzed as a share of those who are not in the labor force (neither employed nor officially unemployed).20

Marginal attachment to the labor force does not vary consistently across income groups. The rate for marginally attached workers was roughly equal for those in upper-income and middle-income families at 1.8 percent and 1.9 percent, respectively; the rate for those in LMI families was somewhat higher at 2.3 percent.21 Individuals with lower levels of education are much more likely to be marginally attached to the labor force than those with more education, consistent with generally poorer labor market outcomes for those with less education. Discouraged workers, who accounted for 35.2 percent of all marginally attached workers in the most recent data, typify the marginally attached. Discouraged workers currently are not working and are not looking for work because they believe no jobs are available for them. This belief may derive from many factors, including a perceived shortage of jobs, discrimination, insufficient qualification, or a chronic illness or disability. The distinction between discouraged workers and other marginally attached workers is that discouraged workers are not actively seeking a job because they feel a search would be futile.22

Underemployment

Challenges to the LMI labor market extend beyond unemployment to “underemployment,” which typically is defined as an insufficient amount of work, but often is more broadly defined to include those who are working at an occupation that requires education, training and/or experience below those attained by the worker.

Among the employed, millions are part-time workers who would prefer a full-time job. Part-time employment is defined by the BLS as less than 35 hours per week. Most workers who are employed part time have sought part-time work intentionally. They may want to work only part time to devote more time to family or other pursuits, or they simply may be uninterested in working full time. Many are part time for economic reasons, however, such as a lack of opportunity for full-time work or slack business conditions.

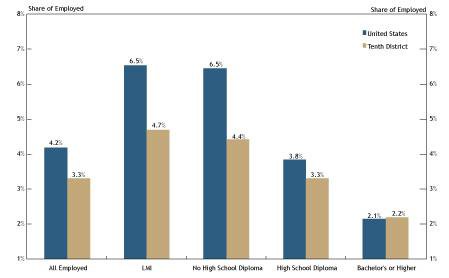

Among all employed workers in the United States in December, 4.2 percent were employed part time for economic reasons (Chart 5). For the Tenth District, a more moderate 3.3 percent of all workers were employed part time for economic reasons, consistent with better overall employment conditions in the District. For District workers in LMI households, a significantly higher 4.7 percent were employed part time for economic reasons.

As with most other labor statistics, the share of the employed working part time for economic reasons was lower for those with more education. Specifically, 2.1 percent of employed people in the United States with a bachelor’s degree or higher were working part time for economic reasons, while 2.2 percent were working part time for economic reasons in the District. Comparatively, the share of employed people working part time for economic reasons was 3.8 percent nationally for those who had completed high school but had not attended college and 6.5 percent for those who had not completed high school. District numbers were 3.3 percent and 4.4 percent, respectively. These statistics are consistent with overall better employment outcomes for those with more education.

Underemployment also arises when workers are employed in jobs below their skill level and experience, but data generally cannot be collected on this phenomenon at reasonable cost and with reasonable precision. A 2013 policy paper from the Center for College Affordability and Productivity estimates 48 percent of employed U.S. college graduates are in jobs the BLS categorizes as requiring less than a four-year college education, with the large majority (37 percent of college-educated workers) in jobs that do not require a high school diploma.23 Most common among these occupations are retail salespersons (24.6 percent), cashiers (10.2 percent), and waiters and waitresses (14.3 percent).

Chart 4: Long-Term Unemployment

Note: In this chart, "District" includes all of Missouri and New Mexico. (Sources: Author Computation; Current Population Survey, Basic Monthly Data [microdata] / National Bureau of Economic Research)

Chart 5: Workers Employed Part Time for Economic Reasons

Notes: The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics considers a worker to be part time for economic reasons if s/he is employed less than 35 hours, would like to have a full-time job, but is unable to secure a full-time job due to slack work or business conditions.In this chart, "Tenth District" includes all of Missouri and New Mexico. (Sources: Author Computation; Current Population Survey, Basic Monthly Data [microdata] / National Bureau of Economic Research)

Affordable Housing

Survey Results

The LMI Affordable Housing Index changed little in the January survey, edging down from 74.6 to 74.0. A value below neutral suggests respondents overall see a diminishing ability of the existing stock of affordable housing to meet current needs. Responses varied across the Tenth District, however. Some survey respondents reported that affordable housing is becoming more available in their communities, and a large majority reported little or no change in the availability (but not necessarily adequacy) of affordable housing.

As with other survey indexes, the affordable housing index reflects changes in conditions, and thus, does not address whether the current stock of housing is sufficient to meet current needs. However, in open-ended comments, most survey respondents reported the current stock of affordable housing is inadequate. In the January survey’s special question on continuing high demand for social services, explanations from respondents were dominated by concerns over increased rents and insufficient growth in wages to cover higher rents. In addition to these concerns about rent relative to income, other factors identified as having kept prospective LMI tenants out of housing include rental standards imposed by landlords (such as restrictions for criminal history, credit history, rental history and income), including for subsidized and otherwise assisted housing developments.

Analysis of Related External Data

External data at the national level show wide variation across geography in rent trends, reinforcing the variation in the responses to the special question on rental affordability in the July 2015 LMI Survey.24 In that survey, as well as in comments from the January survey, contacts were especially likely to report concerns about rent increases in the Denver area.

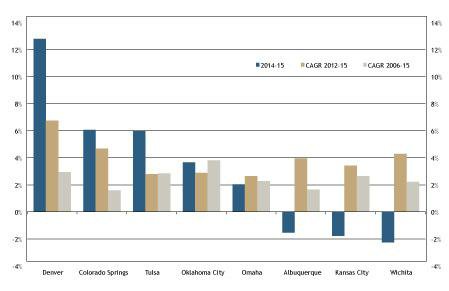

The median rent in the Denver MSA rose at a compound annual rate of 6.7 percent in 2012-15, or about 22 percent for the three-year period (Chart 6). In the last year alone rent in the Denver MSA rose about 13 percent. By contrast, the 2014-15 changes in median rent in most other large Tenth District metro areas were much less steep, ranging from a 2.3 percent decline in the Wichita MSA to 6.1 percent increase in the Colorado Springs MSA.

Within the Tenth District, rental housing is generally more affordable for low-income households than in most other areas in the nation. One way to assess housing affordability is to calculate a housing wage, which is the (gross) hourly full-time wage needed by a renter to afford a median-rent unit while spending no more than 30 percent of income on housing. This wage can be used to judge how affordable market-rate rental units are for households by geography and income level.

Colorado has the highest housing wage in the District for a typical two-bedroom unit at $19.89, just over the national housing wage. It ranks 15th among all states. Other District states have significantly lower housing wages than the national housing wage, with a low of $13.77 in Oklahoma, which ranked 43rd. At those wages, the number of weekly work hours required to afford rental housing at Fair Market Rent (FMR) at the federal minimum wage of $7.25 an hour would be 110 in Denver and 82 in Oklahoma City.26

These statistics assume a one-earner household and do not account for statutory premium wages that may be paid for those who work more than 40 hours in a week.

Chart 6: Rates of Growth in Tenth District Residential Rents (sorted by last year's growth)

Note: CAGR is a compound annual growth rate. Thus, for 10 percent growth over a two year period, the CAGR would be [(1+CAGR)(1+CAGR)]-1 = 10% (Source: Author's calculations / U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, 50th Percentile Rents)

Access to Credit

The LMI Credit Access Index remained steady in the last half of 2015, moving modestly upward to 88.7 in the January survey from 85.2 in the July survey. This result is just under the historical peak for the index of 89.3 reached at end-of-year 2014. Although the index value signifies continued deterioration, it is only modestly below neutral. A large majority of respondents reported no change in access to credit.

The most telling signal of the slowing deterioration of credit conditions for LMI consumers is the lack of comments about credit conditions in the last two survey periods compared to previous surveys. In particular, there were minimal comments on alternative financial institutions, such as payday lenders, whereas numerous concerns about these sectors have been expressed in previous surveys. An exception is student loans. Many survey respondents expressed concerns about increasing student loan debt burdens and the inability of many of those with student debt, especially among those recently entering repayment, to finance their debt in light of labor market conditions and other costs of living.

Appendix: Diffusion Indexes For Low-and Moderate Income Indicators

Endnotes

-

1

The Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City’s biannual LMI Survey measures the economic conditions of LMI populations and the organizations that serve them. Survey results are used to construct five indicators of economic conditions in LMI communities and two indicators of conditions faced by organizations that serve them. The goal is to provide service providers, policymakers and others a gauge to assess changes over time in the economic conditions of the LMI population.

-

2

An increase in the unemployment rate from 5 percent to 10 percent is associated with an increase of 9 percentage points in the probability of receiving a private financial transfer (Aaron Gottlieb and others, 2014, “Private Financial Transfers, Family Income, and the Great Recession,” Journal of Marriage and Family, vol. 76, pp. 1011-1024).

-

3

Numerical responses from individual states generally are not reported in analyses of LMI Survey results because of concerns over the reliability of small state samples.

-

4

To gain additional understanding about the sharp decline in the assessment of job availability, colleagues at the Federal Reserve Banks of Boston, Chicago, Dallas, San Francisco and St. Louis were asked for any comparable data they had available. The Boston Fed completed a survey at about the same time as Kansas City’s January survey, but questions in the Boston survey ask about job availability relative to the previous year only, and their results were similar to our year-over-year outcome. The St. Louis Fed has an annual survey and had not yet collected results for 2015. Most other Reserve Banks reported a lack of comparable data but reported that growth in job availability in the first half of 2015 was generally positive, consistent with the Kansas City Fed’s July survey. The Dallas District (Texas and southern New Mexico) is most like Kansas City in its energy dependence. Again, the Dallas Fed’s Community Outlook Survey posted an increase in the diffusion index for job availability from 58 to 61, where 50 is neutral, but the latest edition asked about the first six months of 2015. The Dallas Fed no longer fields a community survey, and thus no data are available for the second half of 2015.

-

5

Data are from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, Employment Situation Summary External LinkTable B: Establishment data, seasonally adjusted.

-

6

The District population includes only counties within the District for western Missouri and northern New Mexico.

-

7

This report and past issues are available on the Energy Survey page.

-

8

See Jason P. Brown, 2014, “Production of Natural Gas From Shale in Local Economies: A Resource Blessing or Curse?” Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, Economic Review, vol. 99, no. 1, pp. 119-146. Brown’s research found spillover effects to be more significant in the construction and transportation industries, but the results offer evidence of spillovers into other sectors, such as retail.

-

9

Chad Wilkerson, 2015, External Link“How Much Is the Oil Downturn Hurting the Overall Oklahoma Economy?External Link” The Oklahoma Economist, June 12.

-

10

The CPS is a joint effort of the BLS and the U.S. Census Bureau. The monthly survey of about 60,000 U.S. households is the primary source for many U.S. labor statistics, including the official unemployment rate. Extensive demographic data also are collected. The response rate of about 90 percent significantly exceeds the rates for most regular U.S. government surveys. For this report, data from individuals’ survey responses were used to tabulate a variety of labor statistics by income group and for the Tenth District. Equivalent U.S. statistics are provided for comparison. The “headline unemployment rate” for states is reported monthly.

-

11

Statistics also were computed for the entire United States across all income classes and other cohorts defined in this report and then compared to similar statistics posted by the BLS to its website. Statistics computed using CPS data were highly consistent with official statistics reported by the BLS.

-

12

Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, The Tenth District Economic Databooks.

-

13

Unemployed workers and households of unemployed workers likely will have some income during the period of unemployment. Especially common is income offered by unemployment insurance, but also through earnings of other household members, public assistance, assistance from family or friends, or other sources.

-

14

Causality moves in both directions and is likely much stronger from education to income. Here the term “LMI worker” is used broadly to consist of workers in LMI families or those who live in LMI communities.

-

15

Calculated from December 2015 CPS microdata. The U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics typically publishes annual data. For 2015, see External Link“Employment status of the civilian non-institutional population 25 years and over by educational attainment, sex, race, and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity” (table). “High School Diploma” includes those who have earned a General Educational Development (GED) diploma.

-

16

To address LMI individuals and communities while accounting for the difficulty in disentangling employment and income, these workers are defined as those living in LMI households.

-

17

The U.S. government began collecting these statistics in 1948.

-

18

For additional information on economic activity in the Tenth District and District states, see the the Tenth District Economic Databooks.

-

19

The coefficient of correlation for official unemployment rates and long-term unemployment rates for the United States over time is 0.79, demonstrating a strong positive statistical association.

-

20

A more common way to view the degree of marginal attachment to the labor force is through the BLS U-5 unemployment rate. The U-5 unemployment rate includes a measure of the marginally attached as a share of those in the labor force (+ marginally attached).

-

21

Middle-income individuals (households) have incomes between 80 percent and 120 percent of area median income. Upper-income individuals have incomes greater than 120 percent of area median income.

-

22

Most commonly, the other “marginally attached” workers had not looked for work in the past four weeks for reasons such as family responsibilities or transportation problems. See External Link“Ranks of Discouraged Workers and Others Marginally Attached to the Labor Force,” Issues in Labor Statistics, U.S. Department of Labor. Retrieved July 23, 2015.

-

23

Richard Vedder and others, 2013, “Why Are Recent College Graduates Underemployed?” Center for College Affordability and Productivity, January.

-

24

An analysis of responses can be found in the August 2015 issue of External Link"Tenth District LMI Economic ConditionsExternal Link,".

-

25

For a complete analysis of housing wages, see External LinkNational Low-Income Housing Coalition, “Out of Reach,” various years.

-

26

“Fair Market Rent” (FMR) is an alternative measure of residential rents produced by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). FMR is computed primarily to determine payment standard amounts for the Housing Choice Voucher program and several other assisted housing programs. FMR typically is set at the 40th percentile point within the rent distribution of standard-quality rental housing units to ensure that a sufficient supply of rental housing is available to program participants (to qualify for subsidies, rent cannot exceed the FMR). These assisted housing programs subsidize market-rate rental units, and FMR is a market rate (it excludes non-market rental housing in its computation).