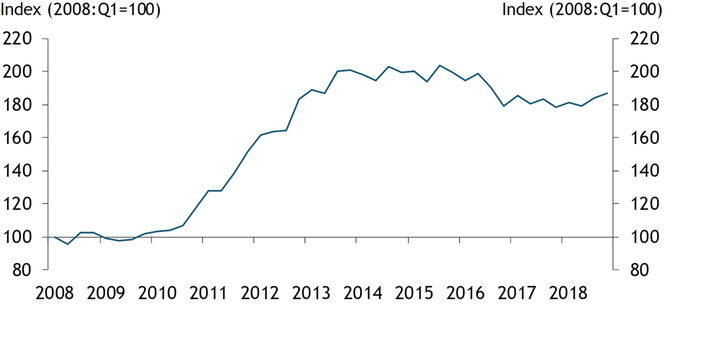

Over the last four years, farm real estate markets have faced pressure due to low commodity prices and deteriorating farm income. From 2013 to 2018, farm income in the United States declined more than 50 percent, and working capital declined 65 percent. Despite these developments, the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City’s Survey of Agricultural Credit Conditions shows farmland values remained relatively stable, declining only modestly in most areas. Indeed, Chart 1 shows that in the Tenth District, cropland values declined only 16 percent from 2013 to 2018. Farmland values in other states across the Midwest and Great Plains declined by similarly modest amounts over this period.

Chart 1: Nonirrigated Cropland Values in the Tenth District

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City.

The relative strength of farmland values has provided some support for the financial health of farm operators. Despite significant declines in liquidity, farm borrowers have remained relatively solvent, and agricultural lenders have drawn on the value of farm real estate when managing risk in their farm loan portfolios. Over the last three years, 20 to 30 percent of agricultural loans have involved restructured debt. A majority of bankers in the Tenth District have reported using increased debt restructuring or increased use of real estate collateral during the current downturn in the agricultural economy in an effort to continue providing credit to agricultural borrowers.

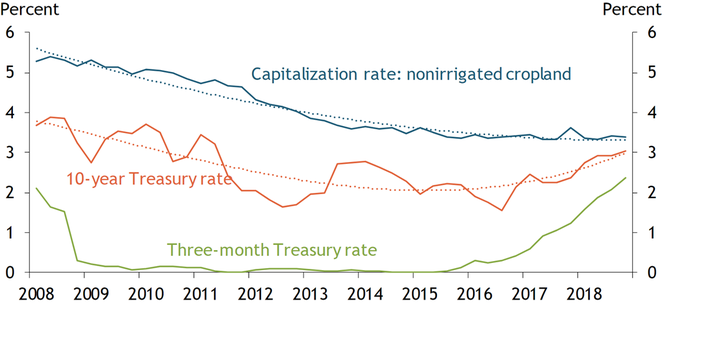

Although farm real estate markets have been relatively stable amid significant declines in commodity prices and farm income, risks of further declines in farmland values appear to have increased. Chart 2 shows that capitalization rates, which can be calculated as the ratio of cash rents to farmland values, have decreased continuously over the past decade, falling from 5.4 percent in 2009 to 3.3 percent by the end of 2018. Capitalization rates approximate the annual rate of return a buyer or investor expects to receive on farm real estate; lower capitalization rates imply, from an investment perspective, that land owners are receiving lower returns on capital invested in farmland.

Chart 2: Capitalization Rates and Benchmark Interest Rates

Note: The capitalization rate is the ratio of cash rents for nonirrigated cropland divided by values for nonirrigated cropland.

Sources: Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City and Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis FRED Economic Data).

The decline in capitalization rates coincided with a rise in interest rates. The gaps between the blue line and the green and orange lines in Chart 2 show that in 2018, the spread between capitalization rates on farmland and risk-free returns narrowed to its lowest level in 10 years. For the spread to return to a more historical level in the current interest rate environment, either cash rents would need to increase or farmland values would need to decline. Given current commodity prices in agriculture, it seems unlikely that cash rents will increase in the foreseeable future. Thus, for the spread to return to a more historically normal level, farmland values would need to decline.

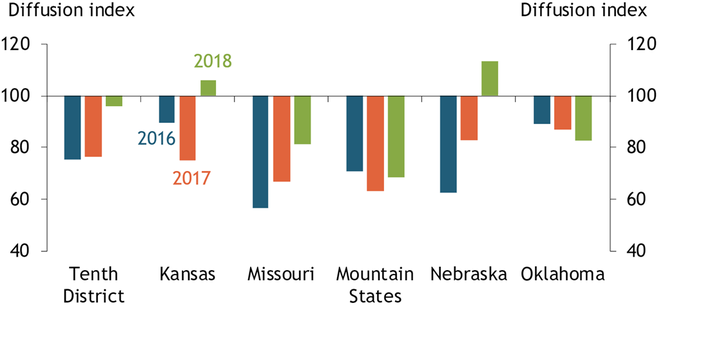

A recent increase in farmland sales in some states also suggests a decline in farmland values could be on the horizon. In 2018, the volume of farmland sales increased in some Tenth District states for the first time in several years. Throughout the downturn in the agricultural economy over the past five years, a persistently low volume of land sales has contributed to the stability of farmland values. However, Chart 3 shows that a majority of agricultural banks in Kansas and Nebraska reported an increase in the volume of farmland sales in 2018 relative to the previous year. Although the volume of farmland sales declined in other parts of the District, the overall pace of the decline slowed considerably.

Chart 3: Volume of Farmland Sales

Notes: A diffusion index above 100 indicates that a majority of bankers reported a higher volume of sales compared with one year ago and vice versa. Mountain States include Colorado, New Mexico, and Wyoming.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City.

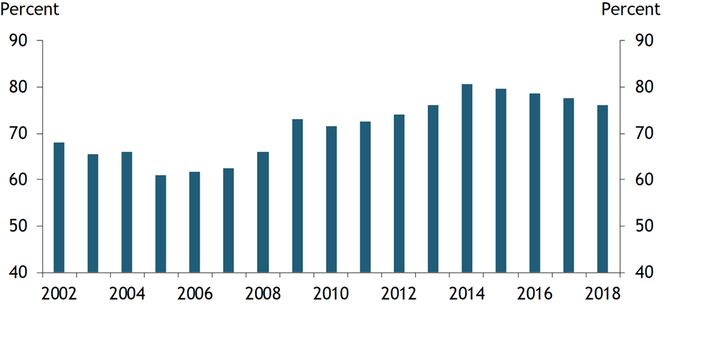

Together, the uptick in farmland sales in some states and the lower spread between returns to farmland and benchmark interest rates suggest farmland values could decline further. Thus far, farmland values have remained relatively stable, and demand for farmland has generally remained steady. For example, despite significant declines in farm income, farmers have generally remained active buyers in farm real estate markets. In fact, Chart 4 shows that farmers accounted for more than 75 percent of farmland purchases in the Tenth District in 2018. One explanation for this trend is that farmers and investors continue to be attracted to farmland as a strategic investment. In addition, farmers and investors may be more willing to accept lower returns on farmland than in the past. However, if farmland sales continue to increase in 2019 alongside persistently low agricultural commodity prices and higher interest rates, farmland values could decline further.

Chart 4: Share of Farmland Purchased by Farmers

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City.

Cortney Cowley is an economist at the Omaha Branch of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City. Nathan Kauffman is Omaha Branch Executive and a vice president and economist at the bank. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City or the Federal Reserve System.