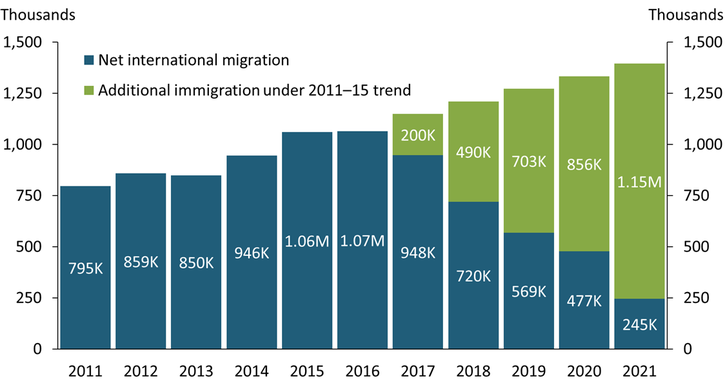

The flow of foreign workers to the U.S. economy has been declining since 2016, when a series of policies to restrict immigration were enacted. Temporary travel restrictions instituted during the COVID-19 pandemic further restricted immigration, bringing levels to a historic low. The blue bars in Chart 1 show that the net number of international migrants that entered the United States each year declined steadily from 2016 to 2021. To illustrate the potential influence of this decline on the size of the labor force, we predict the number of additional immigrants that might have entered each year during this period had the pre-2016 trend in immigration continued. The green bar on the right side of Chart 1 shows that 1.15 million additional immigrants might have entered the United States in 2021 alone. Over the entire 2016–21 period, 3.4 million additional immigrants might have entered the United States, many of whom would have joined the labor force._

Chart 1: Tighter immigration policies and the COVID-19 pandemic reduced immigration to the United States from 2016 to 2021

Sources: U.S. Census Bureau and authors’ calculations.

The potential supply of foreign workers has been further limited by a decrease in the number of nonimmigrant work visas as well as delays in processing work permits for recently arrived immigrants. According to the U.S. State Department, the number of nonimmigrant work visas issued fell from a peak of 5.5 million in 2015 to a low of 1.45 million in 2021. More recently, the pandemic led to substantial delays in processing work permits for recently arrived immigrants; data from U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services show the average processing time increasing from two to four months in 2019 to nine to 11 months in 2021.

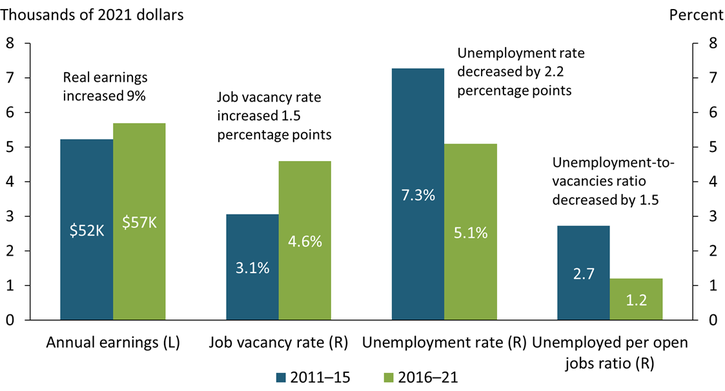

The decline in the flow of immigrants and foreign workers into the United States coincided with a tightening U.S. labor market. Chart 2 compares several indicators of the U.S. labor market before and after immigration flows started to decline in 2016. The first pair of bars shows that mean real earnings have increased by 9 percent from the 2011–15 period to the 2016–21 period, consistent with increased labor shortages and more intense competition for workers._ Moreover, the second pair of bars shows that the job vacancy rate increased from an average of 3.1 percent in 2011–15 to an average of 4.6 percent in 2016–21, implying that about one in 20 jobs was unfilled. The third pair of bars shows that the unemployment rate decreased by 2.2 percentage points on average between the two periods. Finally, the fourth pair of bars shows that the ratio of unemployed persons to vacant jobs decreased by more than 50 percent between the two periods, falling from 2.7 in 2011–15 to 1.2 in 2016–21._

Chart 2: The U.S. labor market has tightened since 2016

Sources: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), U.S. Census Bureau, and authors’ calculations.

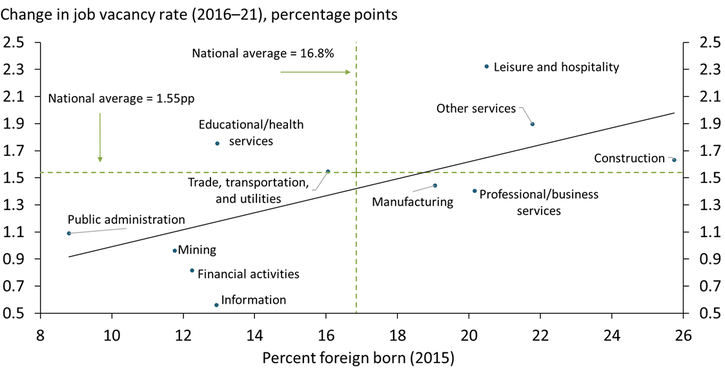

The decline in immigration and coincident increase in labor market tightness suggests that industries that depend more heavily on foreign-born workers may have difficulty filling job openings. Chart 3 shows the relationship between the percentage of foreign-born workers in individual industries in 2015 and the respective change in those industries’ job vacancy rates from 2016 to 2021._ Not surprisingly, all major industries experienced an increase in their job vacancy rate during this period due to factors such as job switching, early retirement, lack of dependent care, and fear of COVID-19. However, industries that had a larger share of foreign-born workers in 2015 tended to experience more significant increases in job vacancy rates from 2016 to 2021, suggesting that reduced immigration exacerbated labor shortages. For example, industries such as construction, leisure and hospitality, and other services (which include, among others, private household workers, laundry cleaning services, and beauty shops) had an above-average share of foreign workers in 2015 and experienced an above-average increase in job vacancy rates from 2016 to 2021. In contrast, industries such as finance, information, public administration, and mining, which had below-average shares of foreign workers in 2015, saw below-average increases in vacancy rates.

Chart 3: Industries with a larger share of foreign-born workers experienced more significant increases in job vacancies

Sources: BLS and U.S. Census Bureau.

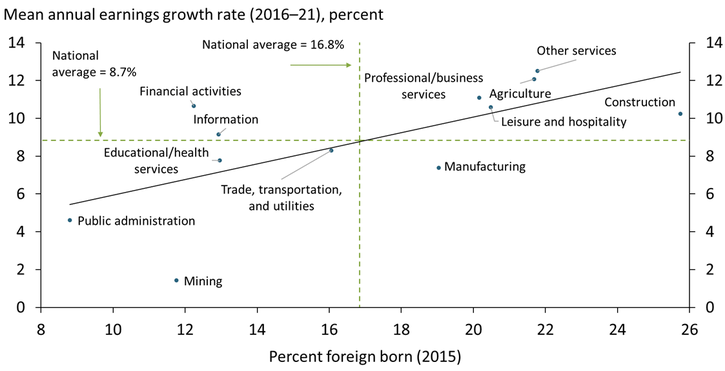

Reduced immigration also appears to have increased wage pressures in industries with higher shares of foreign-born workers. Chart 4 shows the relationship between the percentage of foreign-born workers in each industry in 2015 and the mean annual earnings growth rate in that industry from 2016 to 2021. The top-right quadrant of the chart highlights that industries with an above-average share of foreign-born workers in 2015 experienced more considerable earnings growth. Taken together, Charts 3 and 4 suggest that the reduced supply of foreign labor caused employers to raise wages to attract workers. These trends align with previous studies showing a non-positive relationship between immigration and wages (Card 1990; Borjas 2003). As immigration declines, wages rise, as the reduced labor supply drives employers to raise wages to attract more workers.

Chart 4: Industries with a larger share of foreign-born workers experienced greater increases in real earnings

Sources: BLS and U.S. Census Bureau.

Reduced immigration is likely to affect even those industries that do not depend on foreign-born workers. Immigrants are more likely to fill jobs that allow other individuals to join the labor force—that is, jobs with a significant “job-multiplier effect.” For example, in 2019, more than 25 percent of direct-care workers (such as nursing assistants, home health aides, and childcare workers) were foreign born. The reduced supply of immigrants and the subsequent increase in the cost of direct-care services has likely led some workers to exit the labor force to replace these lost services. For example, Furtado (2016) finds that an increased share of immigrant workers with a high school diploma or less leads to substantially lower market-based childcare prices. Similarly, Cortés and Tessada (2011) find that a greater share of immigrant workers with a high school diploma or less increases the number of hours worked by women in the top quartile of the wage distribution. Thus, immigration may facilitate more workers entering the labor market and increase labor force participation, which is still below pre-pandemic levels.

Even as pandemic-related immigration restrictions and delays wane and immigration levels increase, the demand for immigrant workers will likely continue to exceed the supply of these workers in the absence of broader changes in immigration policy. As a result, industries and regions that depend on immigrant workers may continue to experience labor shortages. Industries that are less able to implement labor-saving technologies to substitute for missing immigrant workers, such as the direct-care industry, will likely experience increasing shortages and costs, creating a further headwind for aggregate labor supply.

Endnotes

-

1

According to the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, around 50 percent of immigrants from 2001 to 2020 joined the labor force within a year of their arrival.

-

2

We compute real earnings from the Current Population Survey (CPS), jointly sponsored by the U.S. Census Bureau and U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), as annual wage and salary income, expressed in 2021 prices. The job vacancy rate is defined using BLS data as the ratio of job vacancies to the sum of total employment and job vacancies.

-

3

The labor market trends shown in Chart 2 also hold if we focus on the 2016–19 period, implying that the tightening of the labor market was not the result of the COVID-19 pandemic alone. For ease of discussion in the rest of the article, we focus on the 2016–21 period as the post-2016 period.

-

4

We use the CPS industry categories to compute the foreign-born share by industry categories to match BLS job vacancies and employment data by industry.

References

Borjas, George J. 2003. “External LinkThe Labor Demand Curve Is Downward Sloping: Reexamining the Impact of Immigration on the Labor Market.” Quarterly Journal of Economics, vol. 118, no. 4, pp. 1335–1374.

Card, David. 1990. “External LinkThe Impact of the Mariel Boatlift on the Miami Labor Market.” ILR Review, vol. 43, no. 2, pp. 245–257.

Cortés, Patricia, and José Tessada. 2011. “External LinkLow-Skilled Immigration and the Labor Supply of Highly Skilled Women.” American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, vol. 3, no. 3, pp. 88–123.

Furtado, Delia. 2016. “External LinkFertility Responses of High-Skilled Native Women to Immigrant Inflow.” Demography, vol. 53, no. 1, pp. 27–53.

Elior Cohen is an economist at the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City. Samantha Shampine is a research associate at the bank. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the positions of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City or the Federal Reserve System.