Labor and Real Estate Markets Support Nebraska Households

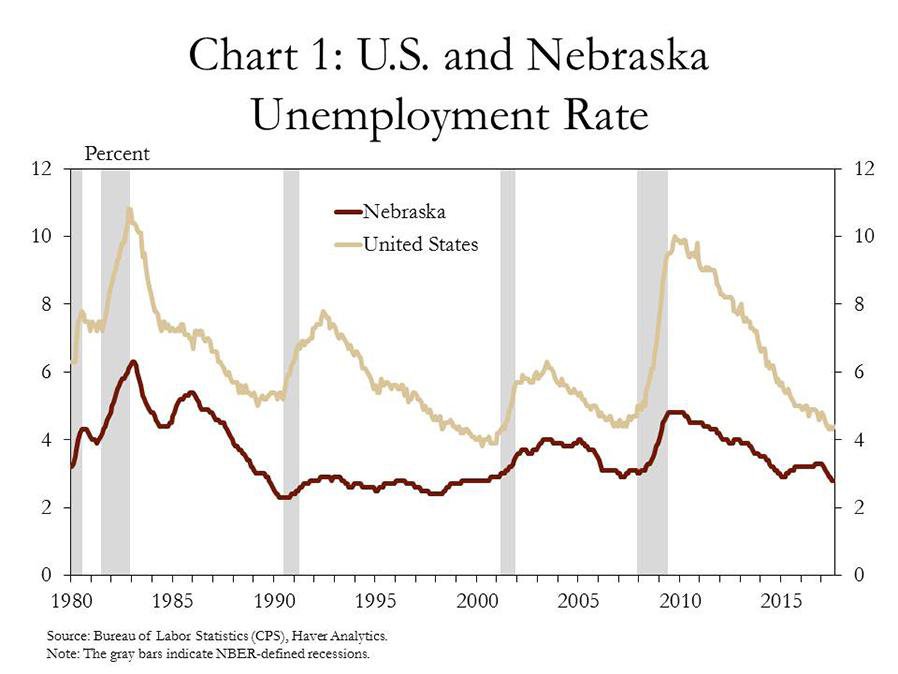

Employment in Nebraska remained strong through 2017. In October, Nebraska’s unemployment rate fell to 2.7 percent, the lowest since the late 1990s, and remained there in November (Chart 1). Similar to historical trends, the unemployment rate in Nebraska consistently has remained below the national rate throughout the most-recent economic expansion.

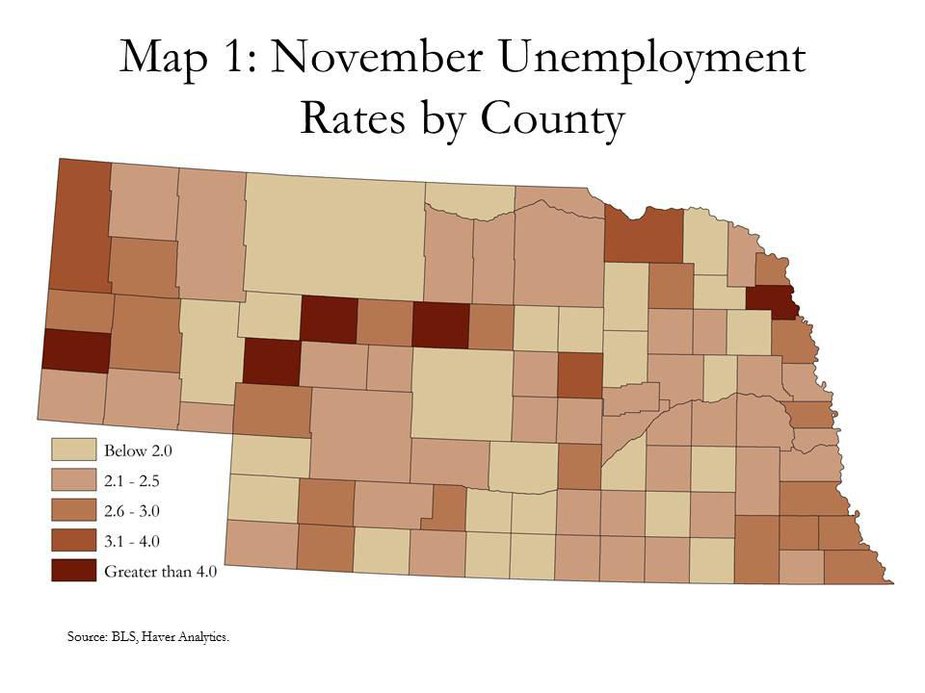

Unemployment rates remained very low across the state in 2017. As of November, only five of 93 counties reported unemployment rates above 4 percent (Map 1). Only these five counties had an unemployment rate higher than that of the nation in November. Much of the state—both in area and population—exists in an environment of extremely tight labor markets.

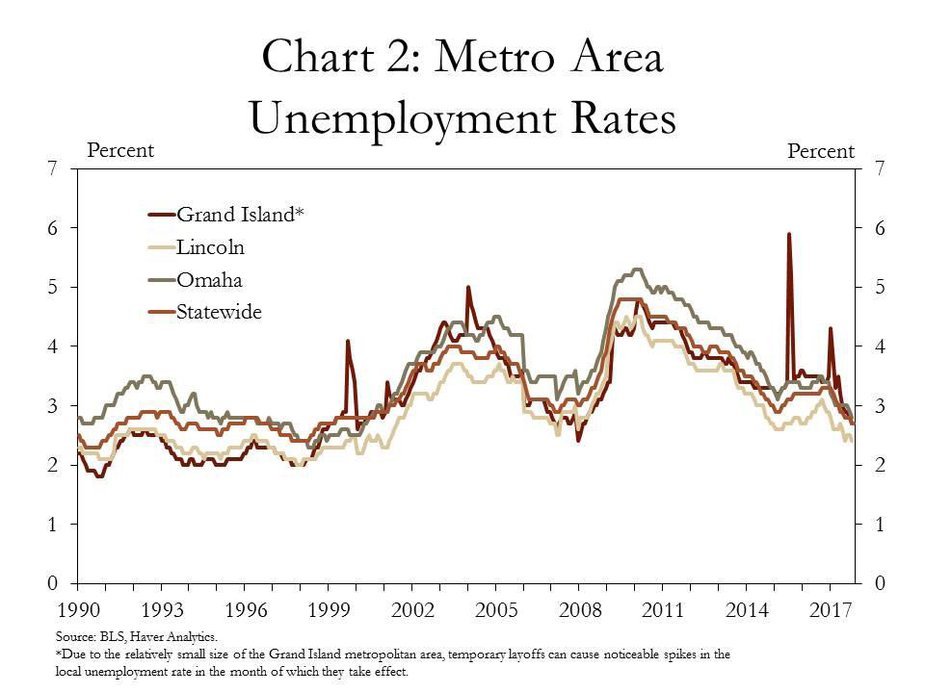

Each of the state’s three metropolitan areas also recorded unemployment rates less than the national rate. In 2017, labor markets in each of these metro areas were the tightest in a decade or more. Grand Island’s rate of 2.7 percent is the lowest since March 2008; Lincoln’s rate of 2.4 percent is the lowest since March 2001; and Omaha’s rate of 2.8 percent is the lowest since July 2000 (Chart 2).

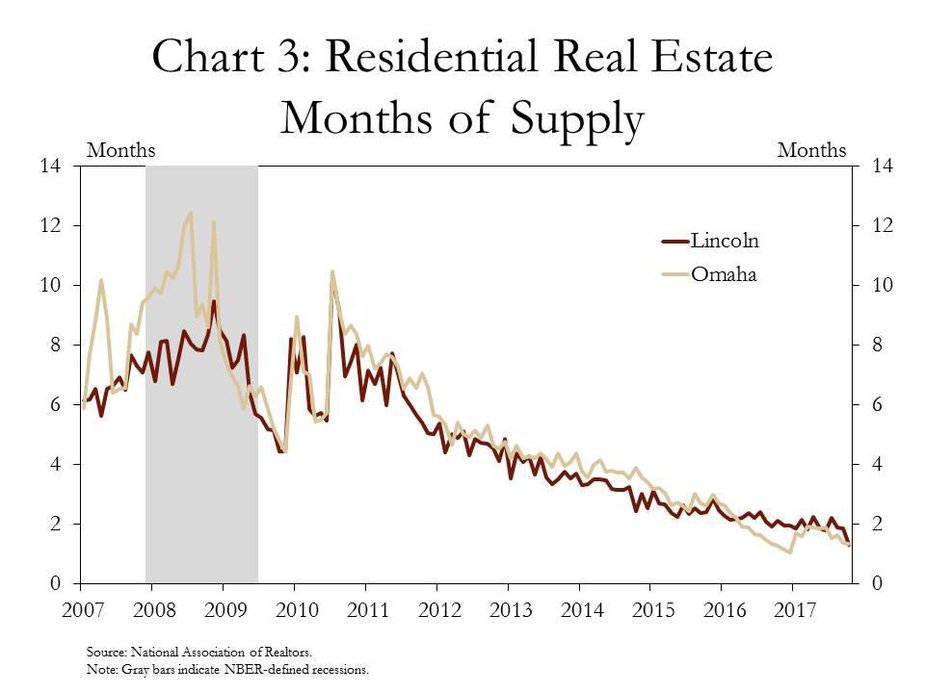

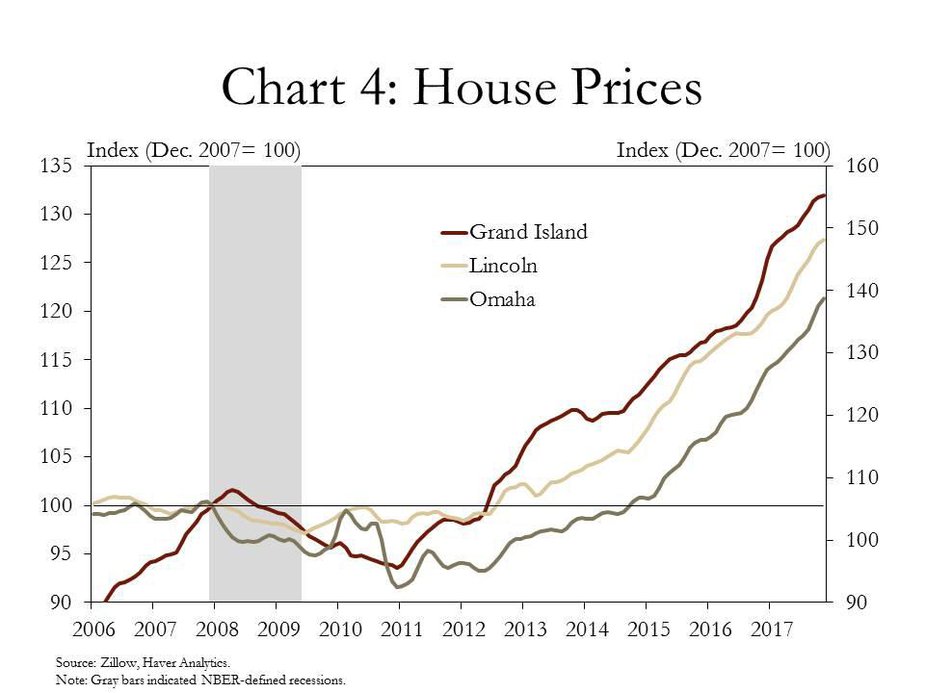

In addition to labor markets, real estate markets also highlight persistent strength in the state’s economy and are a key indicator for household optimism. Driven by strong ongoing demand and limited construction of new homes, the supply of homes in both Omaha and Lincoln has fallen considerably below that of 2007, prior to the Great Recession (Chart 3). The limited number of homes on the market has continued to push up residential real estate prices across the state’s metropolitan areas (Chart 4). In November, the average price of a home in Omaha was 21 percent higher than the months leading up to the Great Recession (nearly a decade ago). In Lincoln and Grand Island, the average price of a home has increased 27 percent and 32 percent, respectively, over the same period.

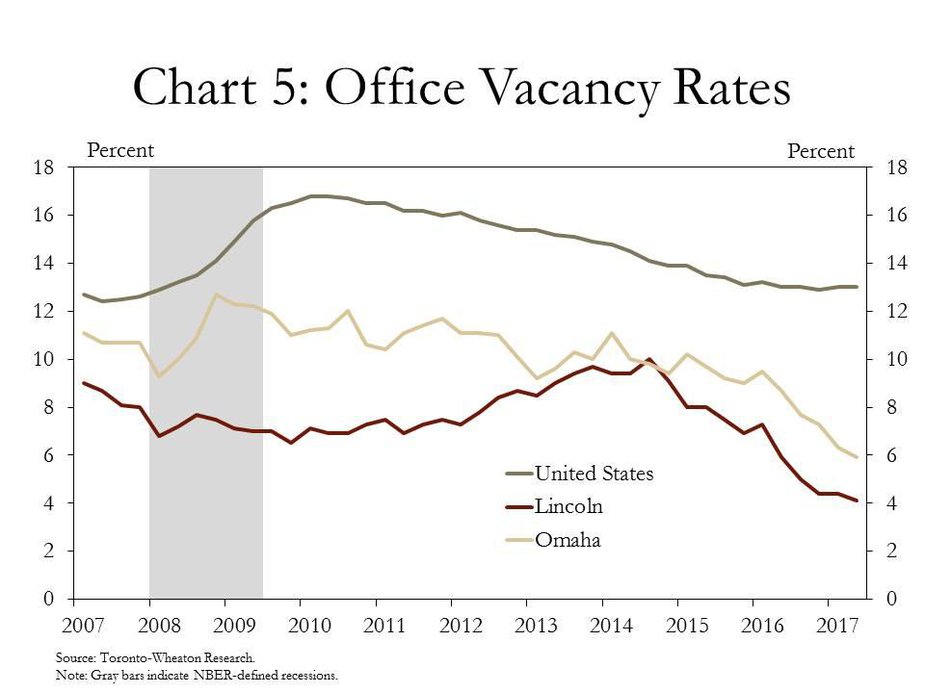

Similar to residential markets, commercial real estate markets also strengthened in 2017 in both Omaha and Lincoln. Office vacancy rates, a headline indicator for commercial real estate markets, continued to fall in both metros in 2017 to a level well below the nation (Chart 5). In addition, the vacancy rates of both Omaha (5.9 percent in the second quarter) and Lincoln (4.1 percent) have remained significantly less than what was observed prior to the last recession for several quarters.

Rural and Agricultural Headwinds Persist

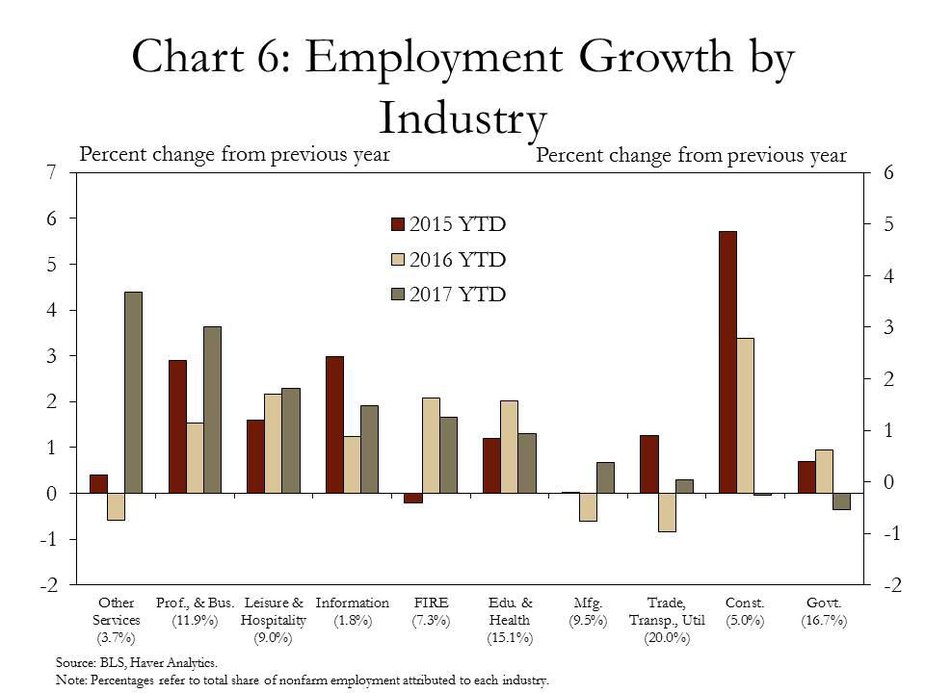

The strength of the state’s economy generally has been broad-based despite ongoing challenges in agriculture and in rural areas. All private sector industries, except construction, continued to add jobs in 2017 (through November) when compared with the previous year (Chart 6). Importantly, employment in each of the state’s three largest, private sector industries advanced in 2017, in contrast to a year ago. Moreover, as an indicator of strength in the general business environment, employment in professional and business services expanded 3.6 percent, its largest amount in several years.

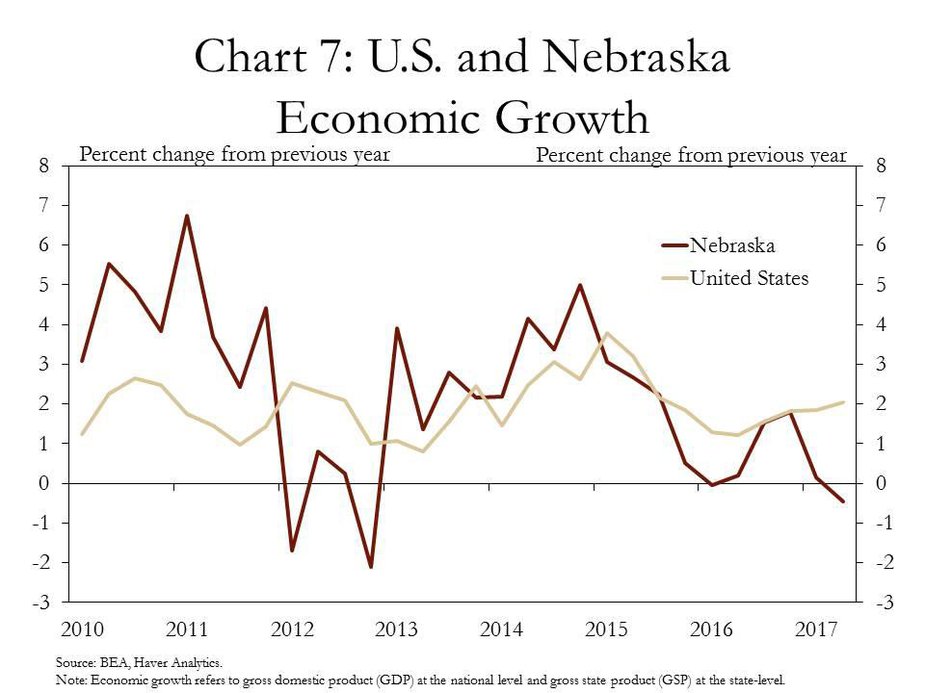

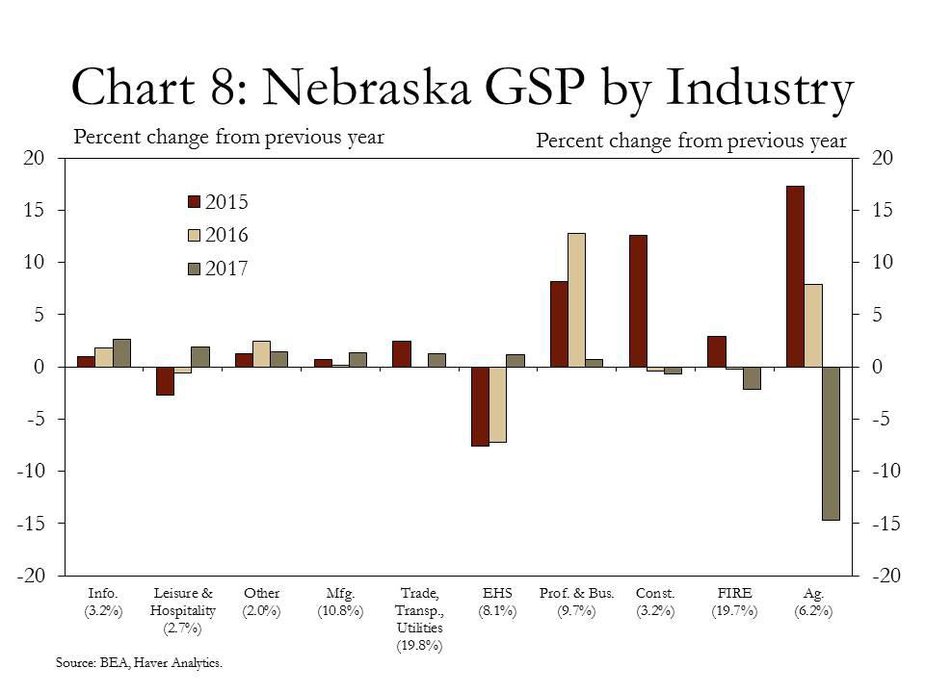

A persistent downturn in the state’s agricultural economy, however, has weighed on the state’s headline indicator of economic output despite broad gains elsewhere. Through the second quarter, Nebraska’s gross state product (GSP) fell 0.47 percent compared with the previous year, in contrast to accelerating growth at the national level (Chart 7). The downturn in agriculture has been a significant driver of the recent divergence between the United States and Nebraska. In fact, through the first half of 2017, GSP attributed to agriculture declined almost 15 percent from the same period a year ago (Chart 8).

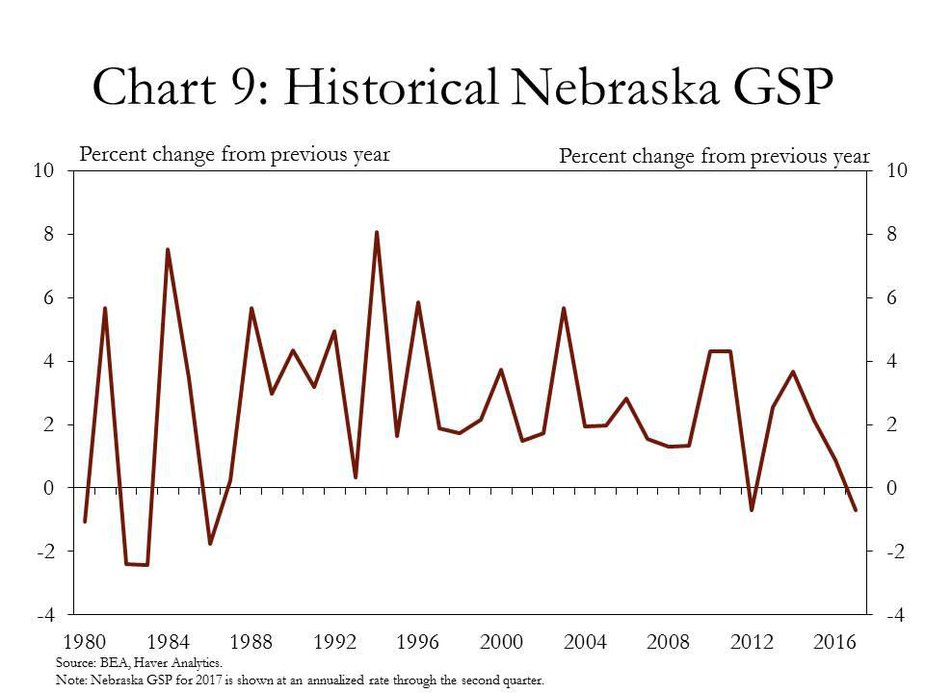

Although concerns remain about a recent slowdown in the state’s economic output, the aggregate environment in Nebraska today is considerably more optimistic than during the farm crisis of the 1980s. In the 1980s, annual economic output declined sharply as the challenges in agriculture began to emerge (Chart 9). Nebraska’s GSP fell in consecutive years in the early 1980s, and again in 1986, before rebounding to a steadier path in the 1990s and early 2000s. Although economic output has fallen in Nebraska again this past year, due largely to developments in agriculture, the decline has been significantly more modest.

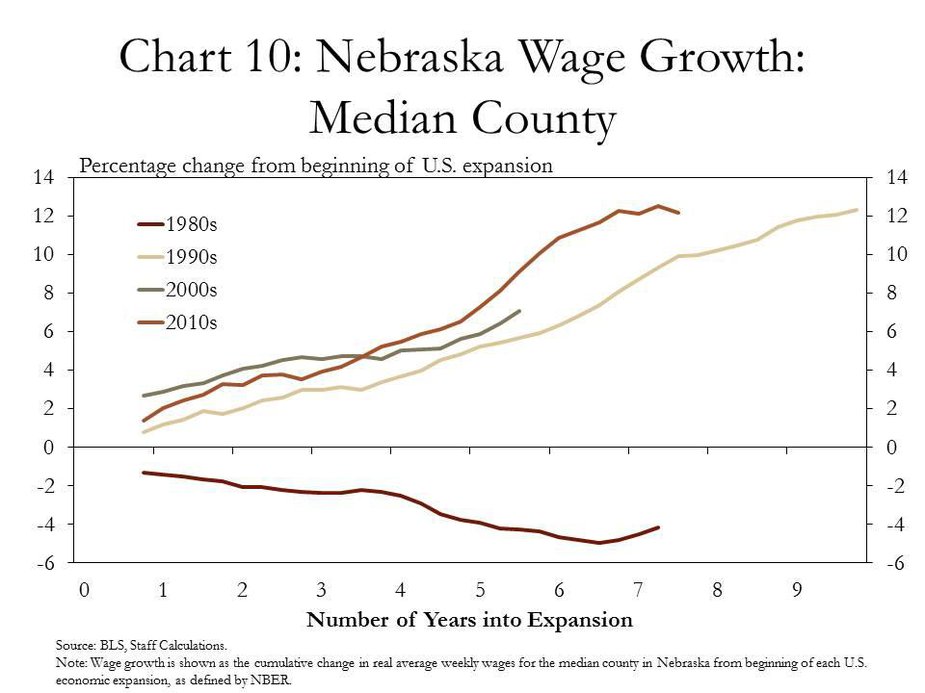

In addition, the recent downturn in the state’s rural economy has had little effect on wage growth throughout the state, in contrast to the 1980s. During the U.S. economic expansion that followed the recession of 1981-82, the median county in Nebraska experienced a 4.2 percent decline in real wages by the end of the expansion in mid-1990 (Chart 10). Cumulative wage growth for the median county during the most recent U.S. economic expansion (which began in the third quarter of 2009), has actually been slightly stronger than each of the previous two expansions. As of the second quarter of 2017, wages have increased for the median county by 12.1 percent since mid-2009.

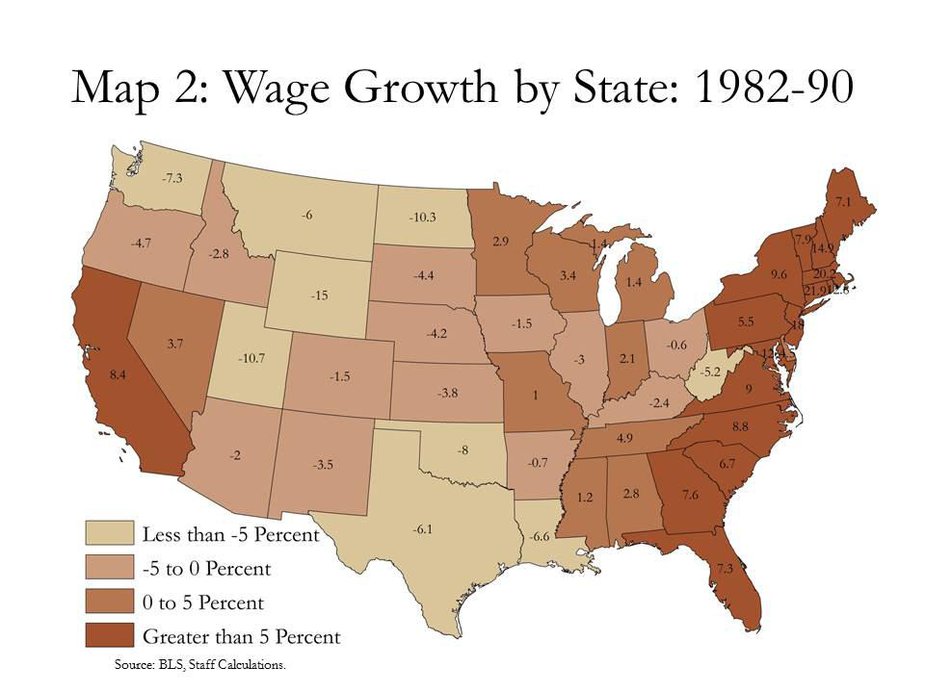

Beyond Nebraska, the agricultural crisis of the 1980s had a significant impact on the growth in wages for the general population throughout the country’s rural states. In general, gains in real wages during the 1980s were confined to the East Coast and West Coast. In contrast, real wages declined in the 1980s across large portions of rural America alongside a sharp contraction in the agricultural economy (Map 2).

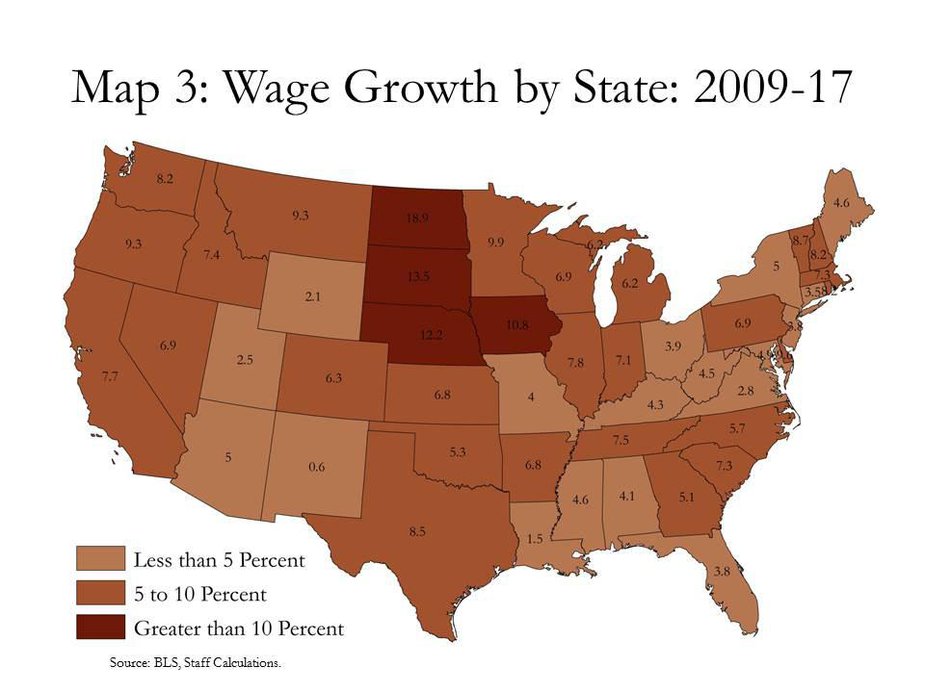

Unlike the 1980s, wages have continued to rise in recent years throughout the country, but particularly in the northern plains states. Over the course of the current economic expansion, wages for the median county in Nebraska have grown at the third highest rate in the nation, likely due to strong demand for labor in sectors outside of agriculture and a limited availability of workers (Map 3). Wage growth in Nebraska generally has been consistent with neighboring Iowa and South Dakota, states that also are highly concentrated in agriculture. These wage gains, at a time when the rural and agricultural economy of the region has weighed on economic output, suggest that other industries have continued to push the state’s economy forward.

Conclusion

Economic and business activity in Nebraska generally remained solid in 2017. Although the outlook in the cattle industry brightened this past year, low crop prices have helped perpetuate challenges in the state’s rural and agricultural regions. Metropolitan areas have continued to drive most of Nebraska’s employment gains throughout the year. Looking forward, despite the challenges of a tight labor market, the state’s metro areas appear well-positioned for further growth alongside broad-based momentum in the U.S. economy.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City or the Federal Reserve System.