Nebraska’s economy began 2020 on what appeared to be solid footing, but has been shocked in ways bearing little resemblance to anything experienced in modern times. As COVID-19 began to spread across the globe from January to March, leading to widespread economic shutdowns, business activity collapsed and a massive number of individuals suddenly were out of work. Although the rapid deterioration of economic conditions in Nebraska was not as severe as other parts of the country, unemployment spiked in April to levels that previously may have been unimaginable. Through June, many segments of Nebraska’s economy have reopened, at least partially, but the economic shock of COVID-19 appears likely to persist for months, if not years.

January to March 2020

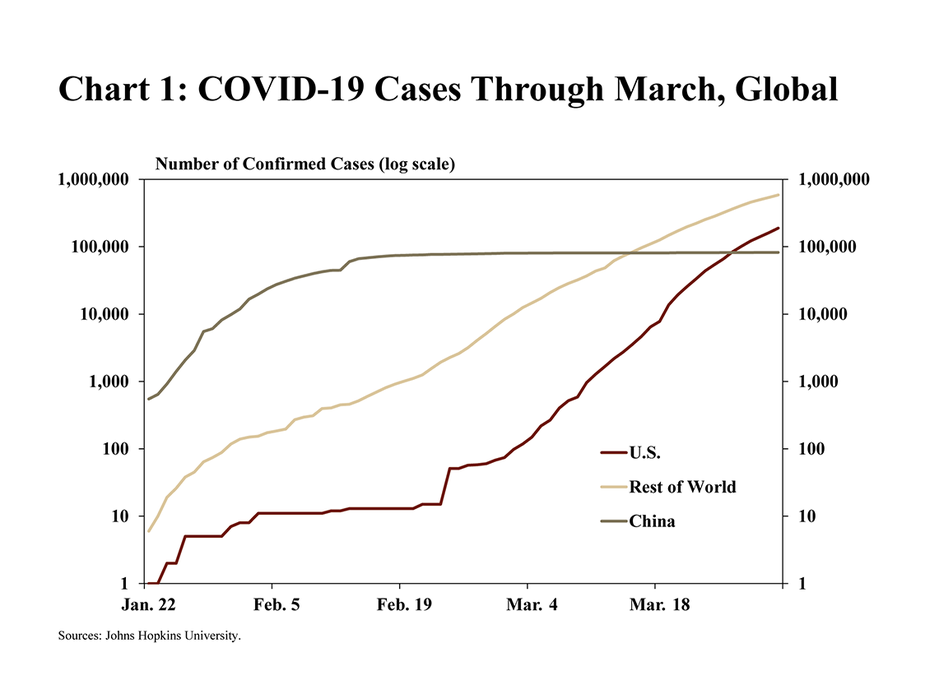

Following initial detections in China in late 2019, the number of COVID-19 cases outside the United States began to increase significantly in February. The first case of COVID-19 was reported in December in Wuhan, a large city in the Chinese province of Hubei. By the end of February, amid a lockdown of Wuhan, the number of confirmed cases in China had increased to about 80,000. At that time, the virus was only beginning to be detected outside China (Chart 1).

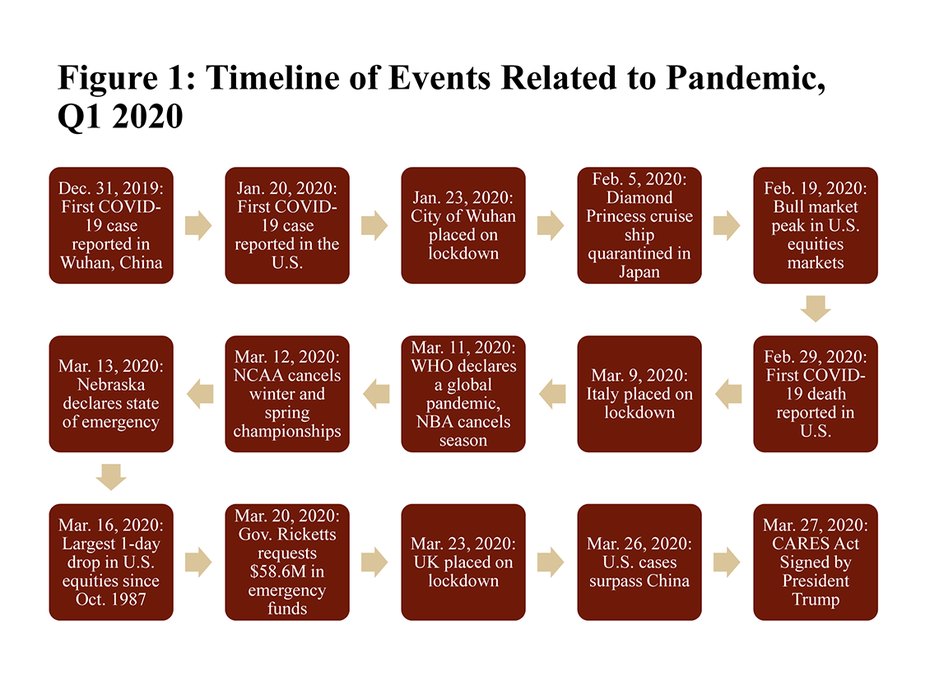

Confirmed infections in the United States began to increase substantially in February and March, leading to extensive closures, cancellations and disruptions. Whereas confirmed cases of COVID-19 in China began to plateau in late February, other countries began to identify significant increases. Two days after Italy placed the country on lockdown, the World Health Organization on March 11 declared a global pandemic (Figure 1). The NBA canceled its basketball season the same day, followed later by the NCAA, public schools, and many other events where people regularly would gather in close proximity.

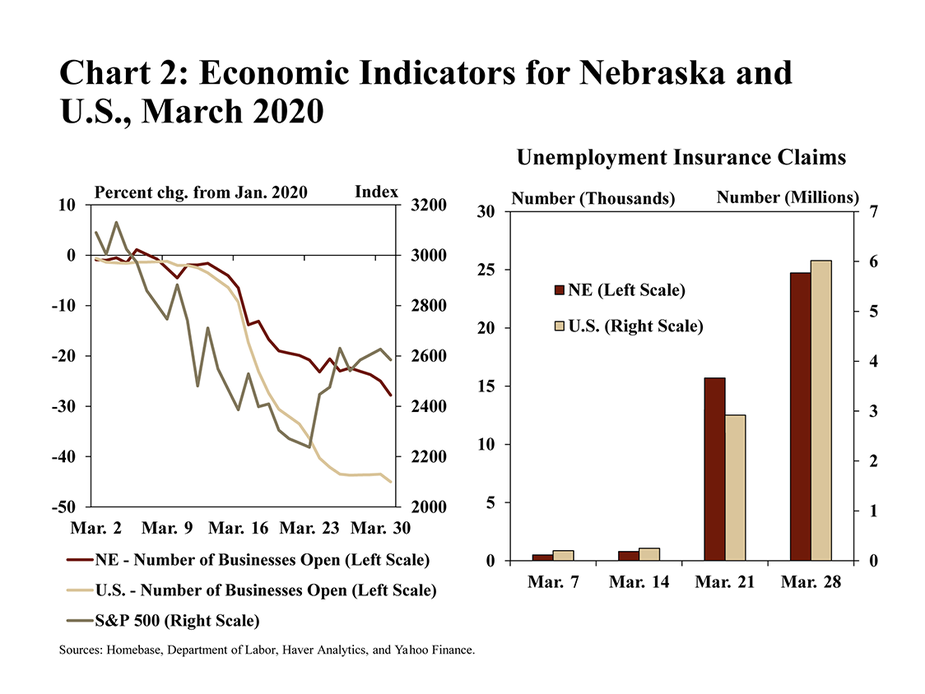

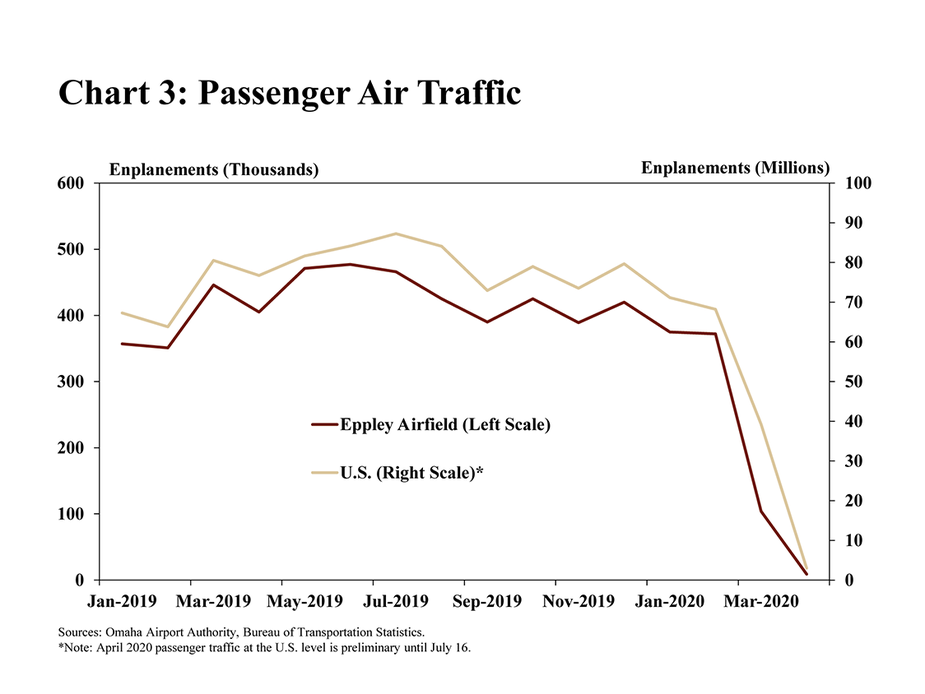

The closure of large numbers of businesses and other institutions in March began to weigh heavily on economic indicators across the country and, to a slightly lesser extent, in Nebraska. Surprised by the speed and severity of the global economic shutdown, U.S. equity markets dropped sharply in March. After peaking February 19, the S&P 500 fell nearly 24% over the next month as businesses across the country closed and uncertainty surged. By the end of March, almost 50% of small businesses in the United States were closed (Chart 2). Even in Nebraska, a state that often weathers economic shocks relatively well, almost 30% of small businesses were closed. With businesses shuttered, at least temporarily, unemployment filings spiked. Activity in industries dependent on the gathering and movement of people had ground to a halt. Air traffic at Eppley Airfield in Omaha dropped more than 90% from February to the end of March, consistent with national developments (Chart 3).

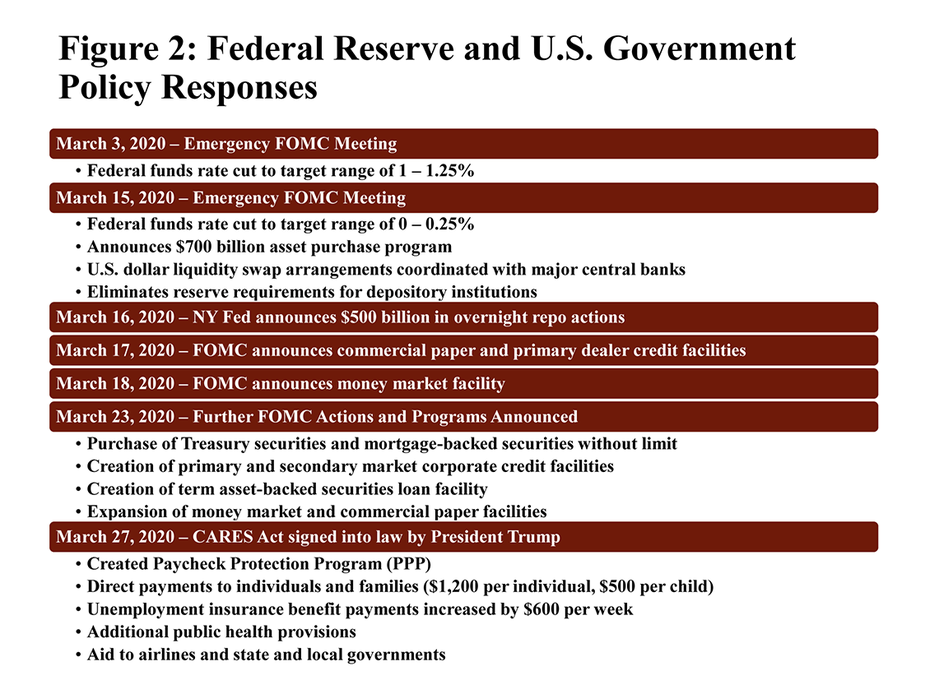

Recognizing the magnitude of the crisis, Congress and the Federal Reserve announced numerous policy actions to provide support to businesses, households and financial markets. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, a $2.2 trillion dollar fiscal support program, was signed into law on March 27. Among other features, the CARES Act created the Paycheck Protection Program, provided financial support to individuals and families through direct payments, and added an additional $600 to weekly unemployment insurance checks. Following an emergency cut to interest rates at an unscheduled meeting March 3, the Federal Reserve subsequently announced numerous programs intended to ensure the proper functioning of various financial markets roiled by a spike in volatility (Figure 2).

April 2020

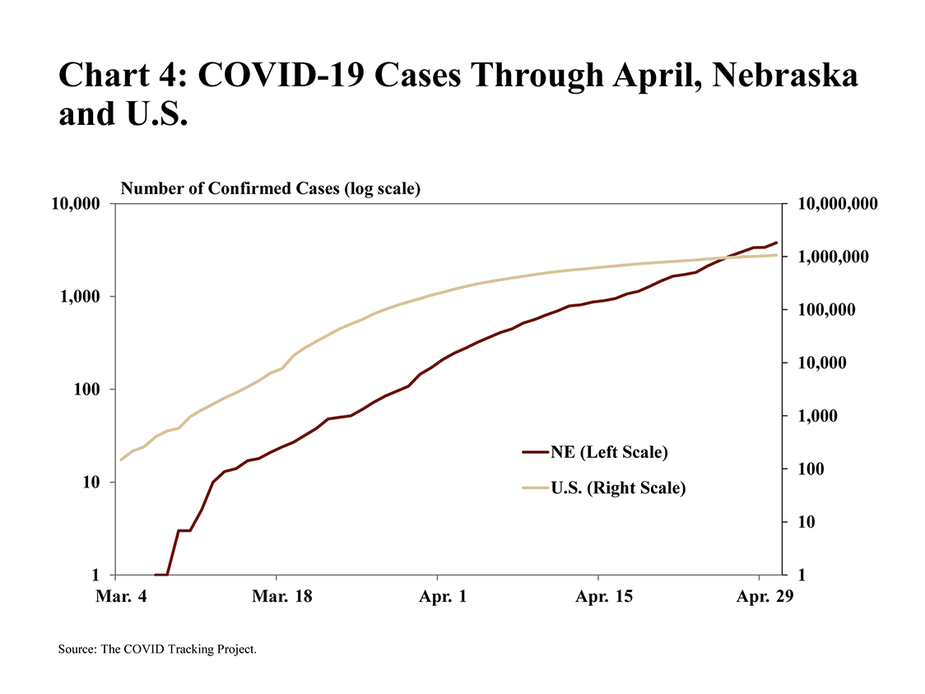

In April, the number of confirmed COVID-19 cases in Nebraska continued to accelerate. While infections in Nebraska generally tracked that of the nation through the end of March, cases in Nebraska increased more rapidly in April (Chart 4). The disproportionate increases in Nebraska appeared to be due, in part, to positive tests at meatpacking plants in Nebraska and the region.

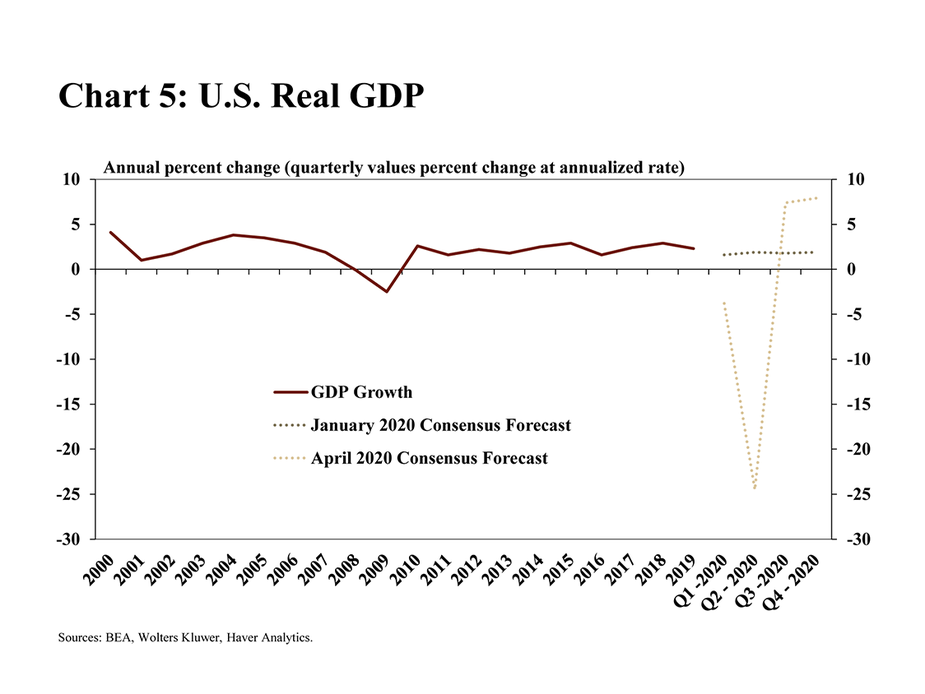

As the shutdown of U.S. and global businesses and institutions persisted through April, economic conditions continued to deteriorate. Prior to the global pandemic, U.S. real GDP was projected to increase at a rate of about 2.0% in 2020, similar to that of recent quarters (Chart 5). The shutdowns associated with the pandemic, however, caused expectations of GDP to be revised sharply lower in the first half of 2020.

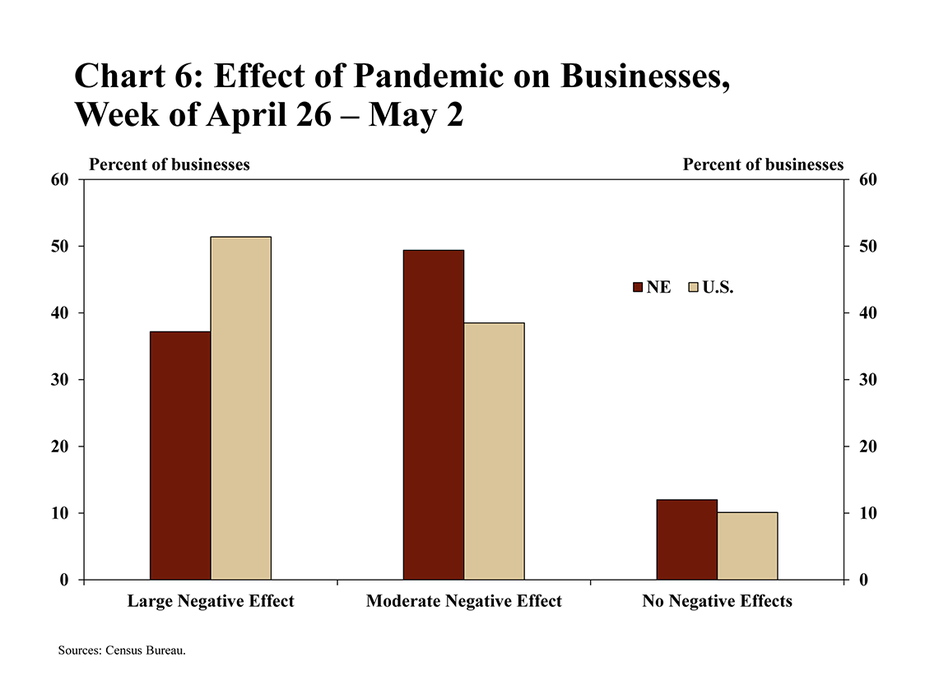

Businesses across Nebraska indicated that the pandemic had a substantial effect on activity, but slightly less than the nation. Survey data collected by the U.S. Census Bureau in April showed 37% of businesses in Nebraska reported that the pandemic had a large negative effect on activity (Chart 6). Nationally, more than half of businesses reported a large negative effect associated with the pandemic.

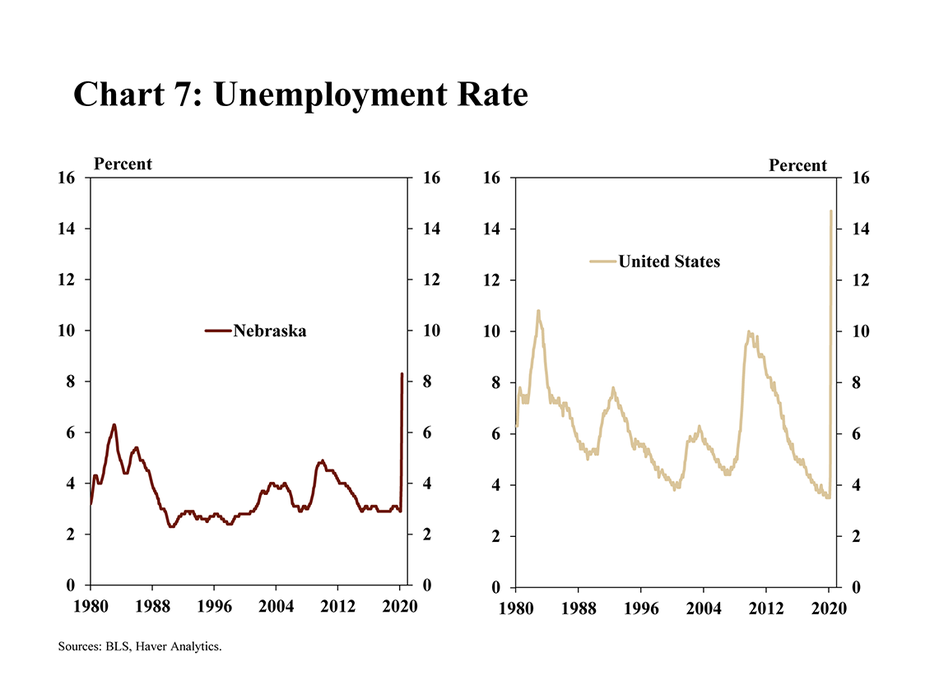

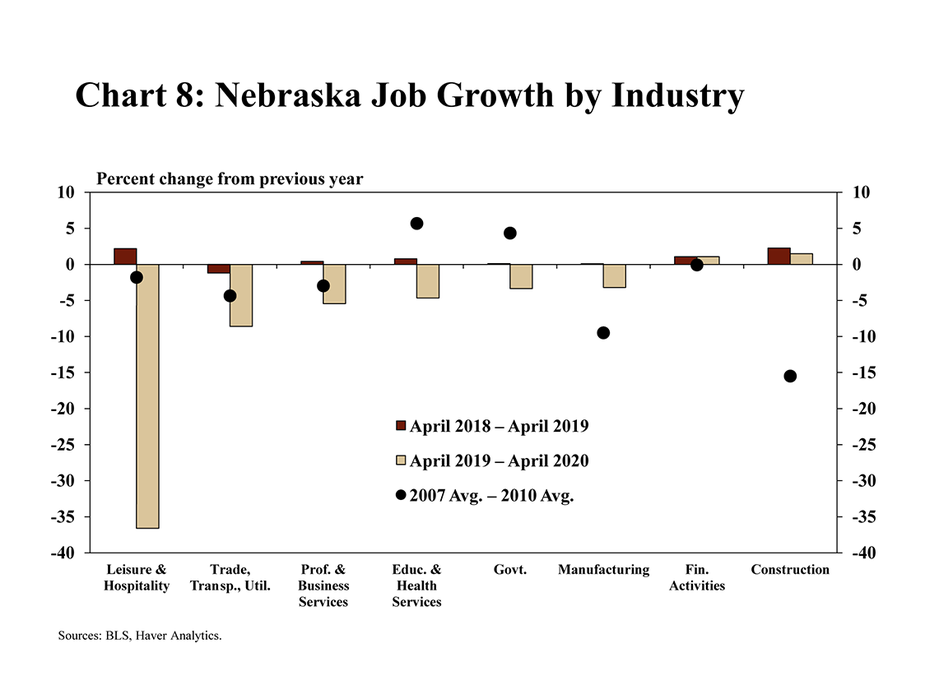

Unemployment in Nebraska also rose sharply in April, particularly in industries dependent on in-person gatherings. Following almost six consecutive years with a jobless rate of less than 3.5%, unemployment in Nebraska spiked to 8.3%, the highest rate since at least the mid-1970s, and well above the peak rate of 4.9% during the Great Recession (Chart 7). The number of jobs in Nebraska dropped about 8%, but the job losses were especially pronounced in the leisure and hospitality industry, which critically depends on large numbers of in-person customers (Chart 8).

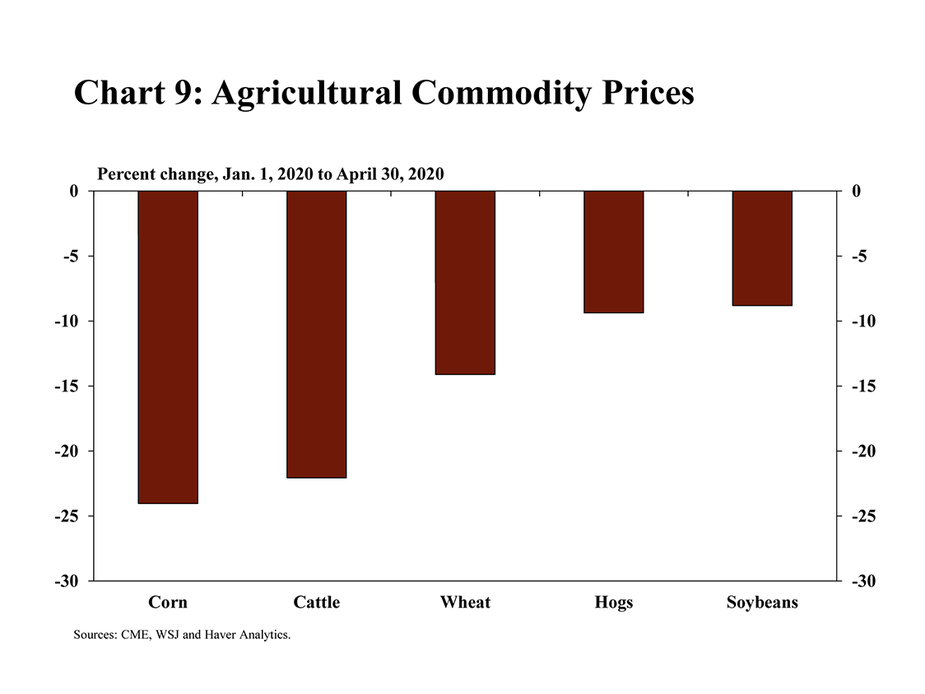

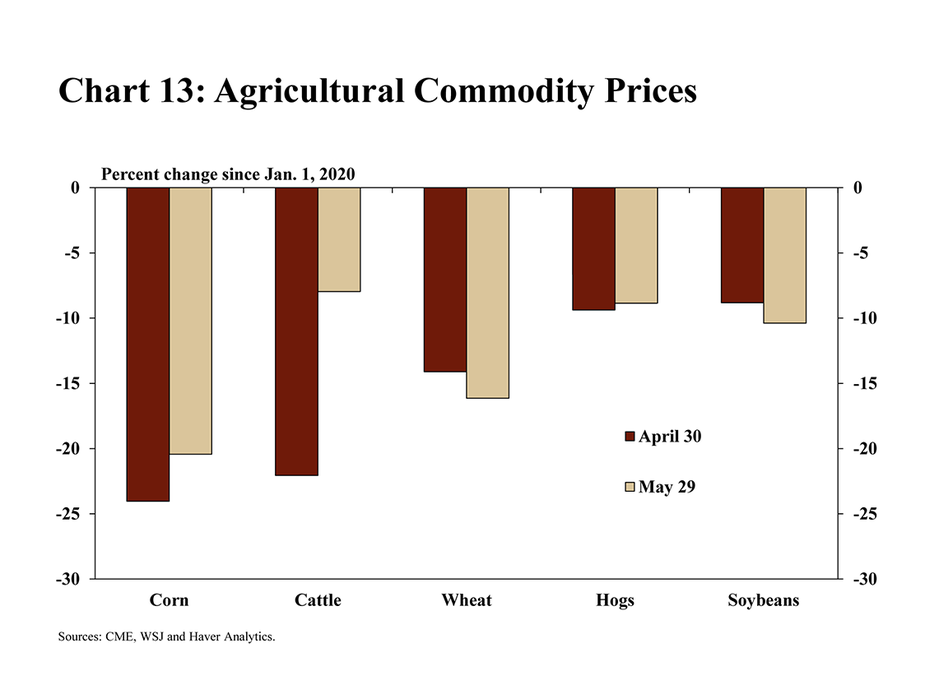

A drop in agricultural commodity prices also weighed heavily on Nebraska’s economy. By the end of April, the price of corn was almost 25% less than at the start of the year, and the prices of other major agricultural commodities also declined significantly (Chart 9). The closure of numerous meatpacking facilities across the state, and the region, likely contributed to the significant decline in cattle and hog prices. A sharp reduction in ethanol production, due to low ethanol prices connected to reduced demand for transportation fuel, also contributed to a decline in the price of corn.

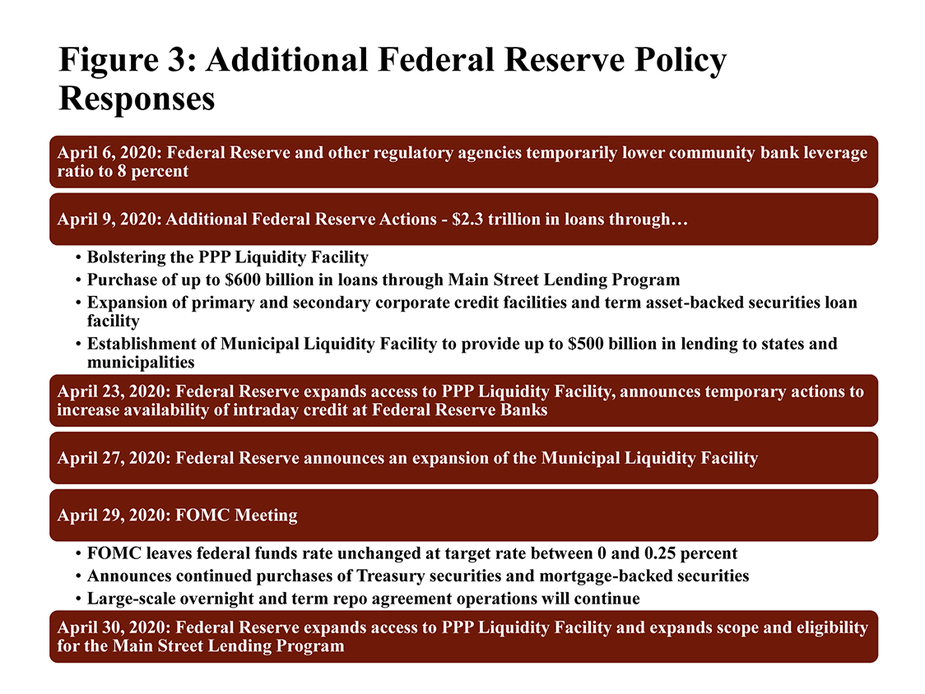

Additional policy responses were announced in April to address the sharp deterioration in economic conditions. As the global shutdown persisted, the U.S. government and the Federal Reserve announced new policies aimed at providing additional support (Figure 3).

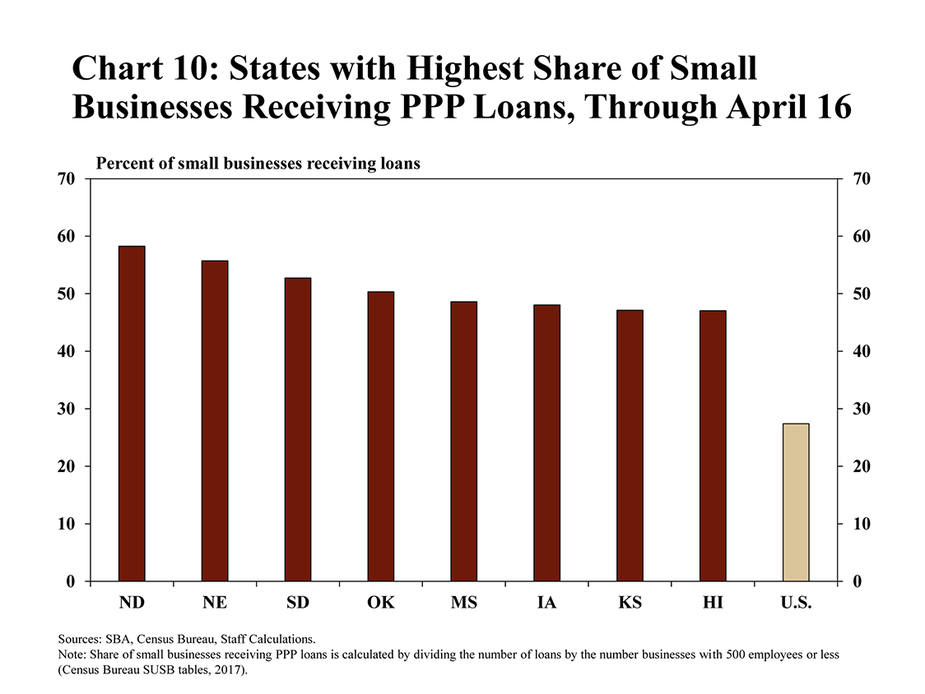

Among the most notable congressional policy responses was implementation of the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP), which provided significant support to Nebraska businesses. The PPP, established the preceding month by the CARES Act and implemented by the U.S. Small Business Administration (SBA), was designed to provide funds to support small businesses being severely affected by the shutdowns. During the early weeks of PPP loan distributions, a large share of small businesses in Nebraska received funding, relative to the nation (Chart 10). Only North Dakota had a higher share of small businesses receive a PPP loan in the first round of funding through April 16. (By mid-June, PPP loan distributions appeared to be more evenly distributed across states.)

May 2020

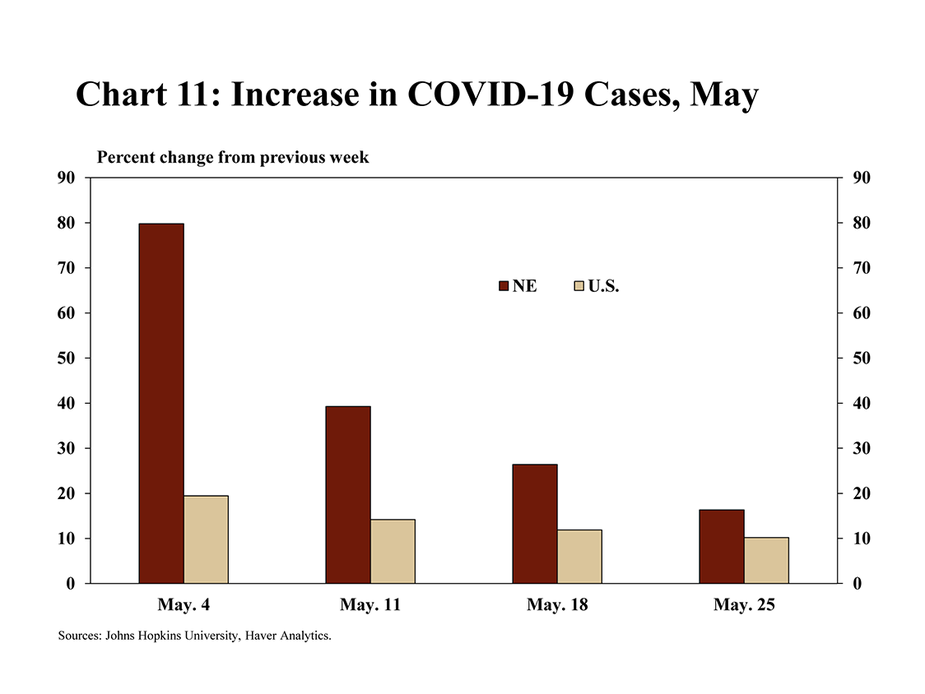

In May, newly confirmed infections of COVID-19 continued to rise, but at a slower pace in percentage terms. In early May, new confirmed cases in Nebraska had been rising by about 80% week to week. By the end of May, new cases in Nebraska were increasing about 15% per week (Chart 11). As June progressed, growth in new cases in Nebraska continued to slow.

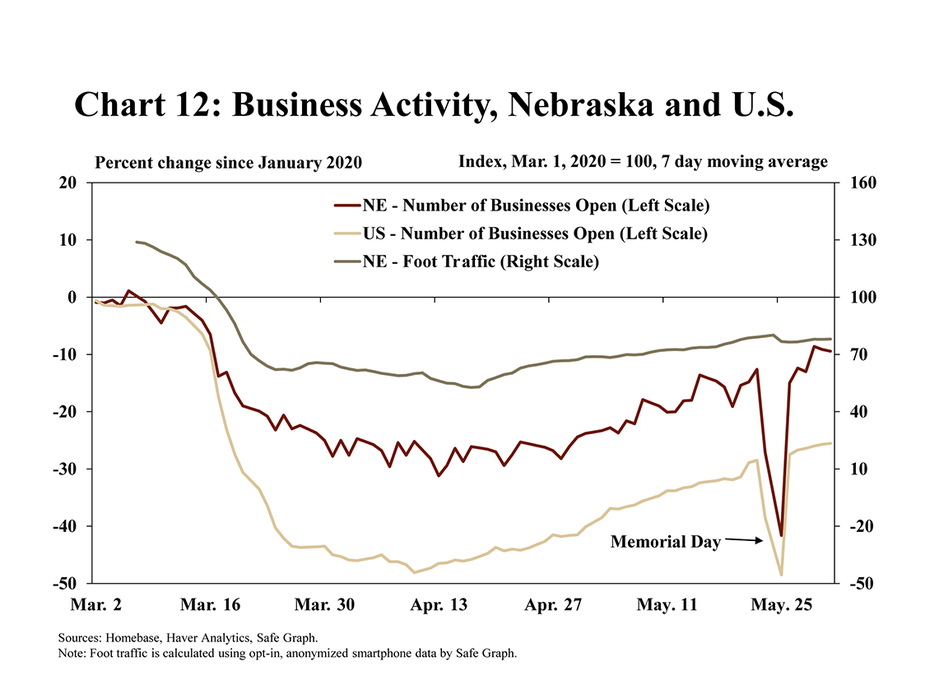

Very gradually, businesses began to reopen and consumers began to venture out, cautiously, from home. By the end of May, less than 10% of small businesses in Nebraska were closed, compared with more than 30% during the most intense period of pandemic-induced lockdowns in mid-April (Chart 12). Aggregated and anonymized tracking data from smartphone devices, available from users who opted in to the tracking, also showed a sharp uptick in foot traffic across the state from mid-April through May.

Agricultural commodity prices also rebounded slightly as key measures of demand began to improve. By the end of May, the price of cattle had improved significantly, but still remained less than at the start of the year (Chart 13). The price of corn also increased slightly from April to May alongside prospects of increased demand for ethanol (and gasoline) due to loosening restrictions on movement, travel and the summer driving season. Despite the modest improvement in agricultural prices, however, most markets remained weak relative to the beginning of the year.

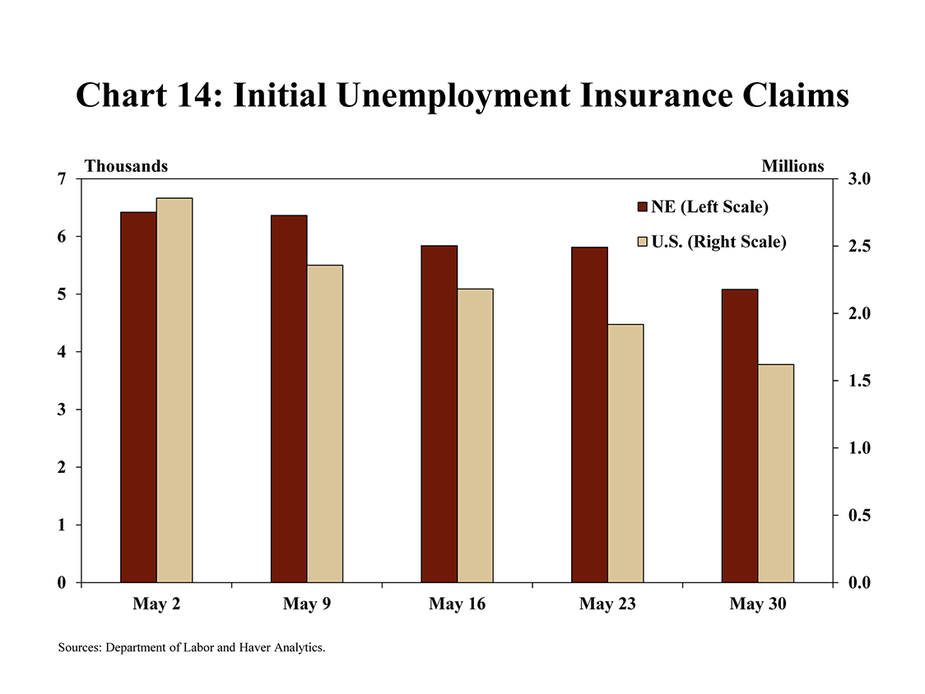

Although businesses began reopening gradually, concerns about unemployment in the region intensified through May as layoffs remained in place and hiring remained suppressed. During May an additional 32,000 individuals filed for unemployment insurance in Nebraska, 60% less than in April, but still significant (Chart 14). While the unemployment rate in Nebraska declined from 8.7% in April to 5.2% in May, it is possible that this rate has not yet fully reflected the economic weaknesses that have emerged in recent months.

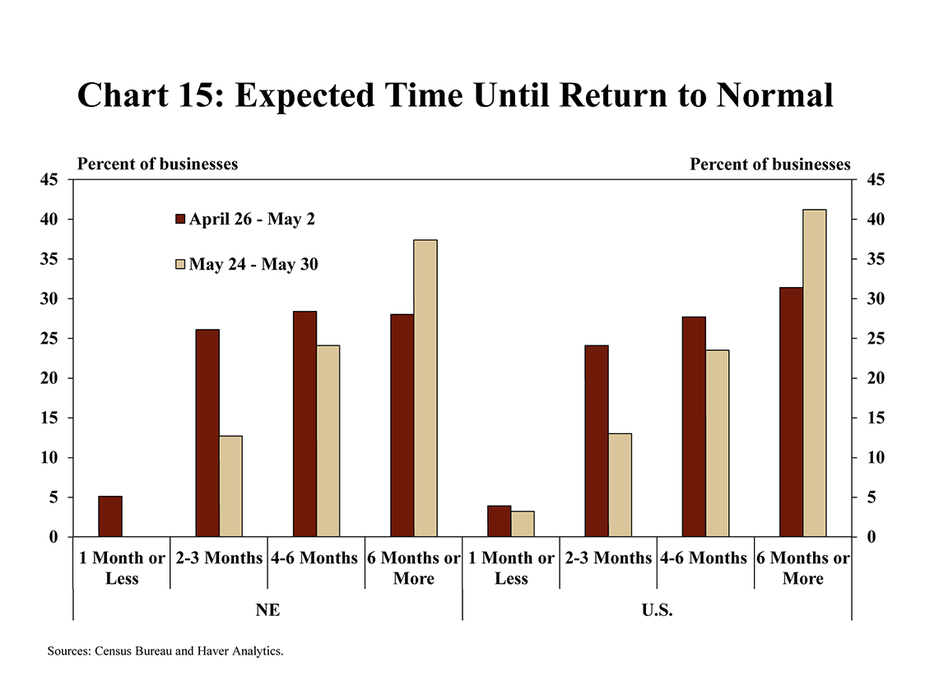

Some economic indicators rebounded in May, but many businesses have suggested they expect a long road to recovery. A survey by the U.S. Census Bureau the last week of May showed nearly 30% of businesses in Nebraska indicated they expect a minimum of six months before levels of activity return to normal, an even larger share than at the end of April (Chart 15).

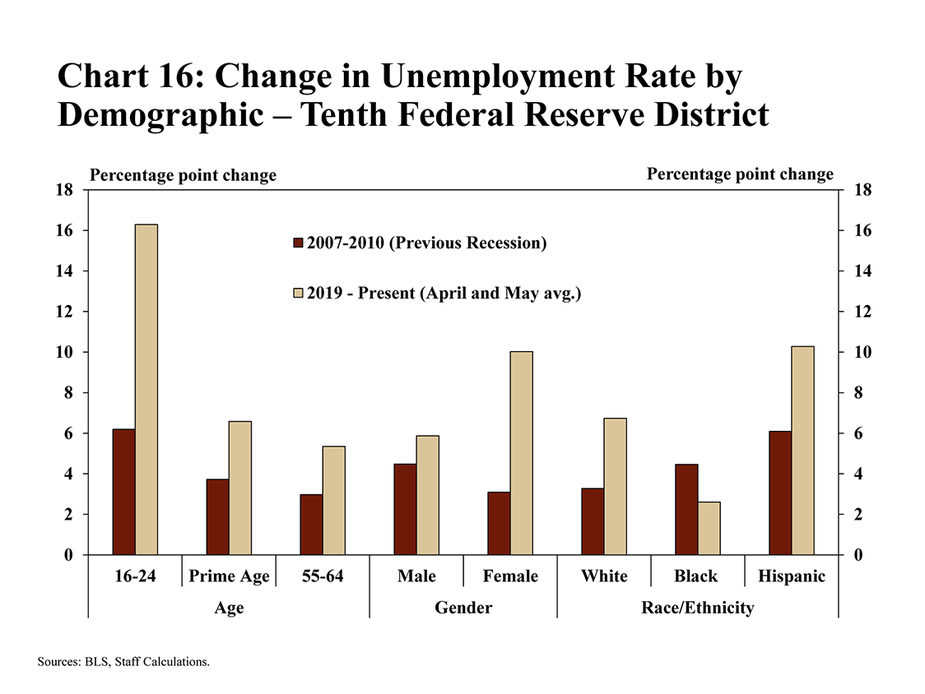

The economic hardships caused by the pandemic also have been spread unevenly across demographic groups. Within the seven-state Tenth District of the Kansas City Fed (Nebraska, Colorado, Kansas, Oklahoma, Wyoming, western Missouri and northern New Mexico), the increase in unemployment from a year ago was most sharp among younger individuals, women and Hispanics (Chart 16). For individuals ages 16 to 24, unemployment increased almost 15 percentage points – from an average of 6.9% in 2019 to an average of 23% in April and May 2020 - well above the increase in the last recession. The unemployment rate for women increased by more than 10 percentage points, from 3.2% to more 13.3%, and the Hispanic unemployment rate increased from just under 4% to more than 14%.

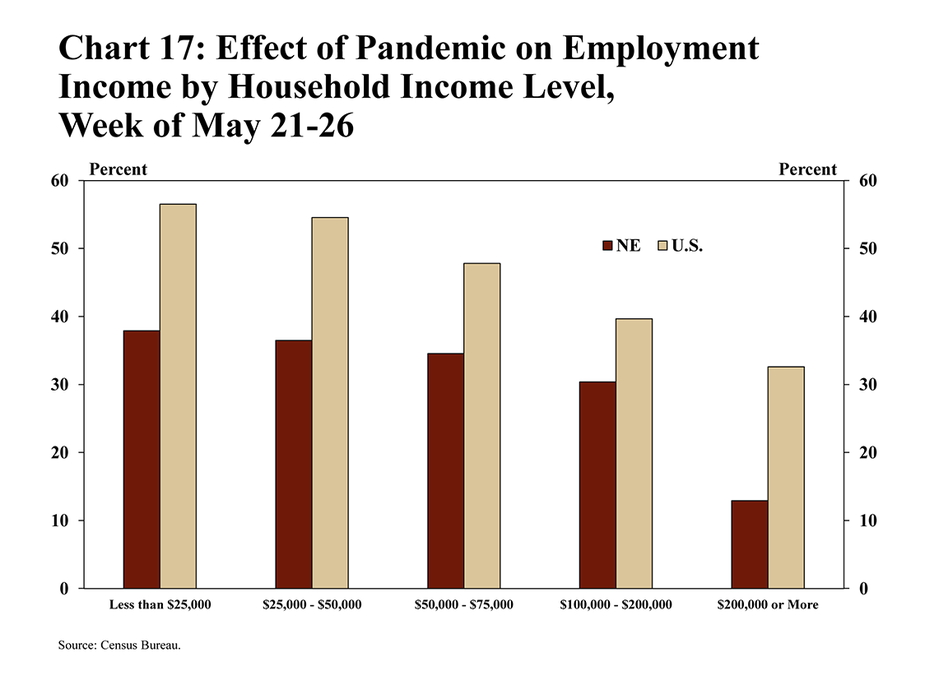

Low-income households also have been affected disproportionately by the crisis. In Nebraska, 38% of households with annual income less than $25,000 experienced a loss of income from employment between March and the end of May (Chart 17). Only 13% of households with annual incomes of more than $200,000 reported loss of income from employment. Nationally, decreases in income also were more pronounced in percentage terms for low-income households, but were even more significant than those of Nebraskans.

Conclusion

Following the severe economic shock from COVID-19, Nebraska’s economy has begun to recover, but uncertainty about prospects for future growth remains high. With the start of summer, business activity appears to be increasing and the spike in unemployment this spring has softened in recent weeks. Significant fiscal and monetary policy support likely has mitigated some of the direst potential outcomes of the economic crisis resulting from the pandemic. However, significant risks remain. The severity of the shock still could lead to unforeseen shockwaves throughout the economy due to a drop in business activity and associated layoffs. A resurgence in the virus could lead to further economic hardship. And while extreme disruption often can lead to longer-term growth, the path forward still may be arduous.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City or the Federal Reserve System.