In recent years, households and students have chosen to relocate in Nebraska at a slightly faster pace in pursuit of education and economic opportunity. A larger number of individuals moving to Nebraska from more distant locations to enroll in higher education or to search for jobs appears to be a key factor that has contributed to a modest improvement in net migration and steady population growth. Looking ahead, a strong and diverse regional economy, in addition to a relatively low cost of living, are likely to remain significant components in both attracting and retaining a highly educated workforce in the state.

Population and Migration

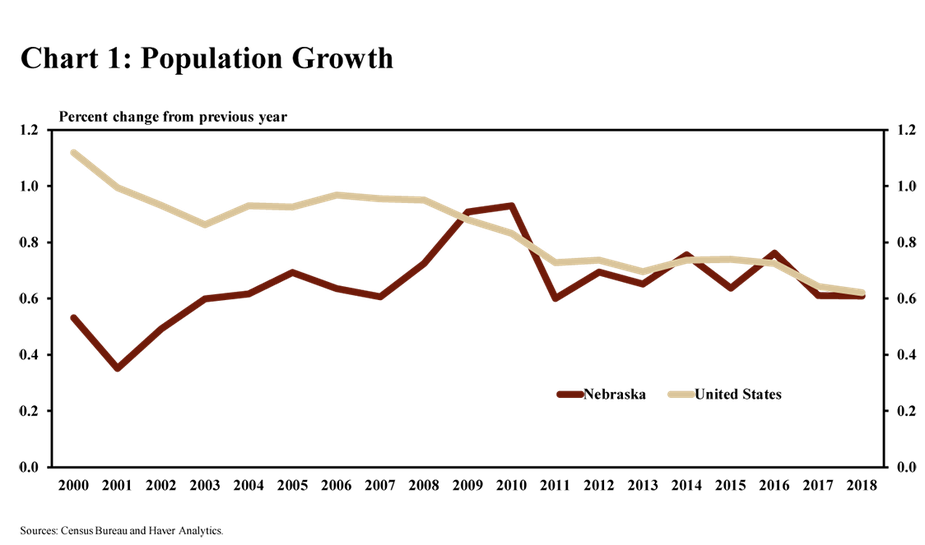

Population growth in Nebraska has remained relatively steady in recent years despite a gradual decline in national growth. As recently as 2002, the growth rate of Nebraska’s population was only half that of the U.S. Since the early 2000s, however, Nebraska’s rate of growth has increased while national growth has declined (Chart 1). Since 2011, Nebraska’s population has increased at a relatively steady pace of 0.6 to 0.7 percent per year, a rate similar to that of the nation.

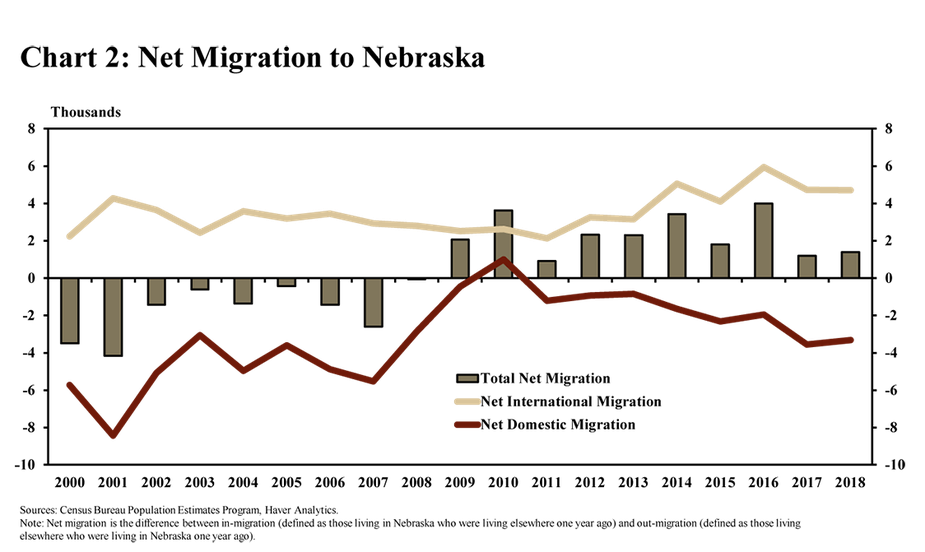

Recently, Nebraska’s population has also edged higher due to individuals relocating from other regions. Although the number of individuals moving to Nebraska from other states has remained less than those leaving, net domestic migration has improved since the early 2000s (Chart 2). In addition, an increase in net international migration from 2011 to 2016 has also supported an overall increase in migration into the state.

The Omaha and Lincoln metropolitan regions have accounted for the largest increases in net migration. In fact, total net migration for the seven counties comprising the Nebraska portions of these metro areas was about 5,400 in 2018. In contrast, net migration for the rest of the state was about -4,000, pointing to an ongoing environment of out-migration from rural areas to urban locations.

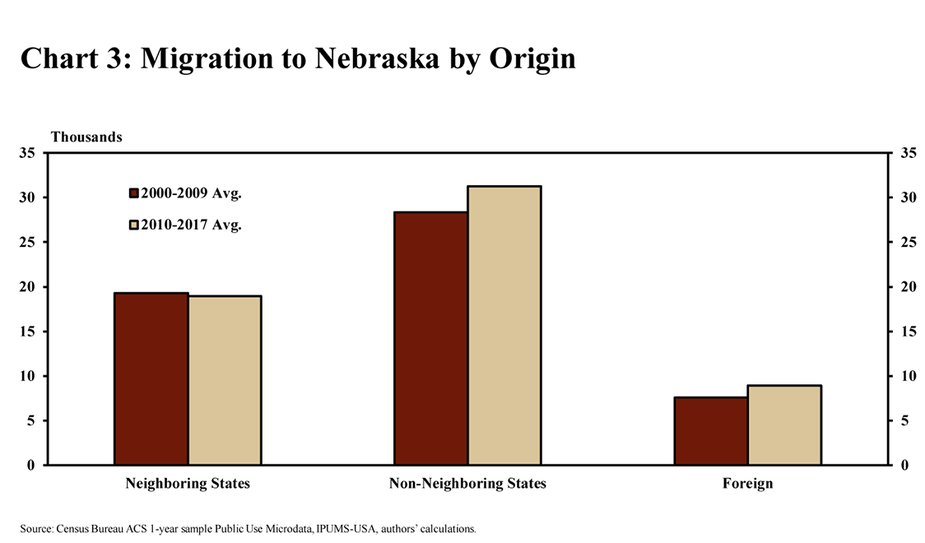

The number of individuals moving to Nebraska from non-neighboring states has contributed significantly to the improvement in net migration in recent years. Over the past two decades, the number of people relocating to Nebraska from neighboring states has remained steady (Chart 3). Individuals moving to Nebraska from non-bordering states, however, have outnumbered those relocating from neighboring states and that number has increased in the current decade. In addition, the number of individuals relocating to Nebraska from international locations has also increased slightly since 2010.

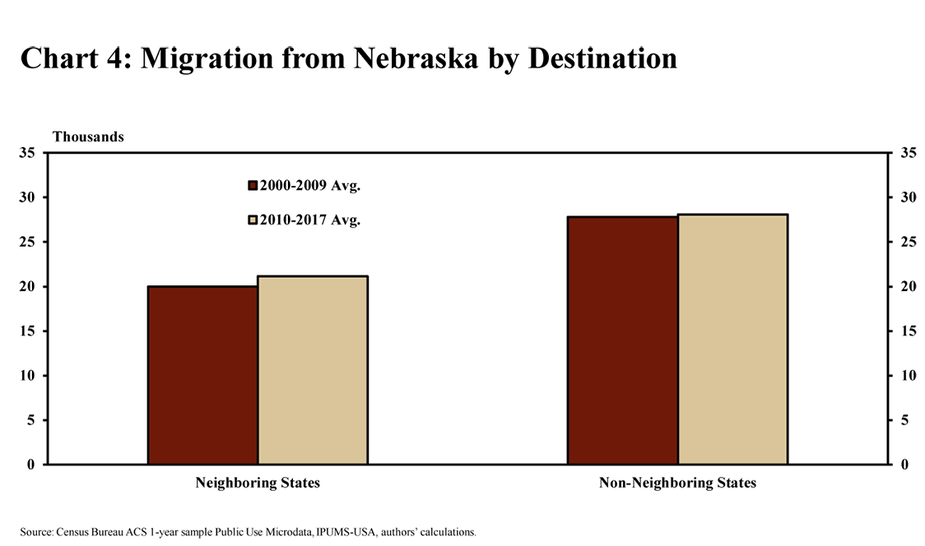

In contrast, the number of Nebraskans relocating to distant states has changed very little over the years. From 2000 to 2009, about 27,800 Nebraskans relocated to a non-neighboring state, on average, each year (Chart 4). This number has remained steady in the current decade. The number of Nebraska residents who have moved to neighboring states has also remained relatively constant, a trend similar to those moving in the reverse direction, to Nebraska from bordering states.

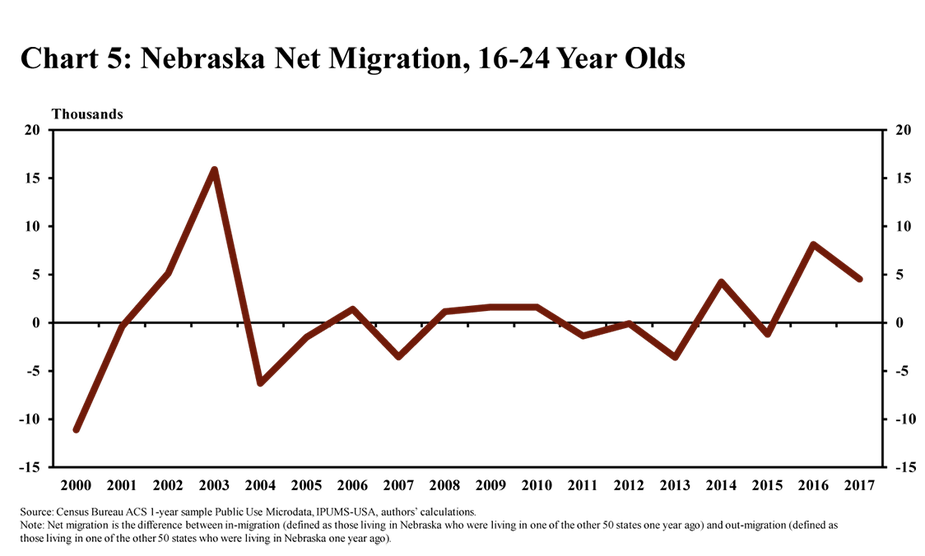

Since 2015, younger individuals have accounted for a large share of people moving to Nebraska and the overall improvement in net migration. In 2016 and 2017, the net migration of individuals between the ages of 16 and 24 was about 8,100 and 4,500, respectively (Chart 5). The net increase in population of younger residents followed an extended period of very limited growth from 2005 to 2015.

Higher Education a Factor in Migration

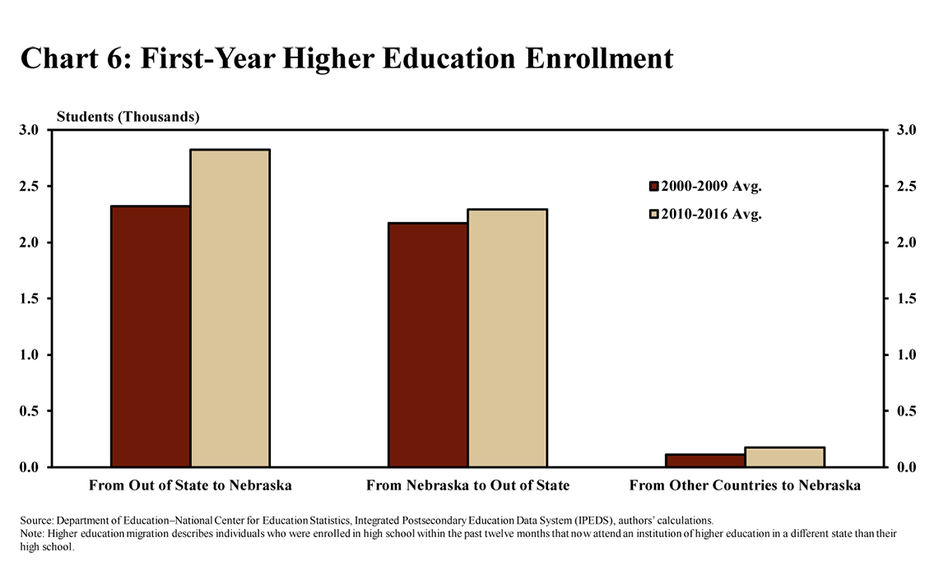

An increase in the number of younger individuals relocating to Nebraska has been due, in part, to their enrollment at higher education institutions from out-of-state locations. Most new students enrolling in Nebraska’s institutions of higher education are from Nebraska. However, in the current decade through 2016 (the latest data available) the number of individuals transitioning from high school in other states and pursuing higher education opportunities in Nebraska has increased by about 22 percent from the previous decade, on average (Chart 6). This increase has exceeded the additional number of Nebraska students choosing to pursue higher education in a different state.

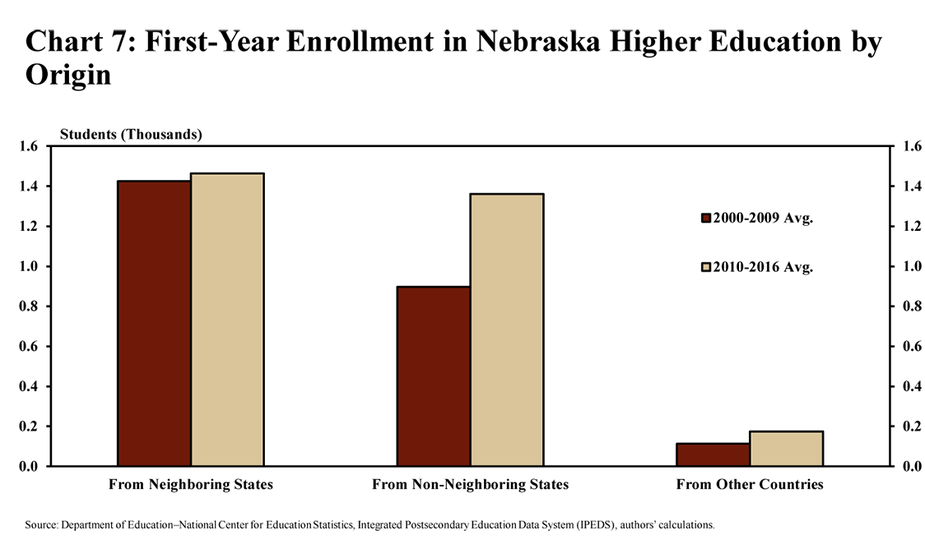

Similar to general population trends, students from more distant locations have contributed significantly to the increase in higher education enrollment. While the number of students from neighboring states enrolling in colleges and universities in Nebraska has remained relatively steady since 2000, the number of students coming from non-neighboring states has increased considerably (Chart 7). In total, about 500 more students moved to Nebraska from a different state in the current decade than the previous one. More than 90 percent of those additional students came from non-neighboring states, with Minnesota, California, and Illinois accounting for a large share.

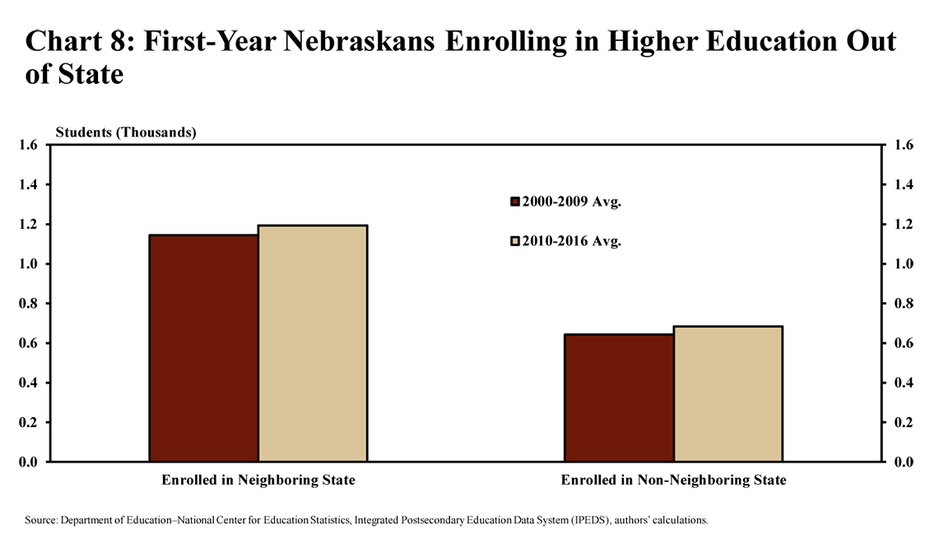

However, Nebraskans choosing to pursue higher education opportunities elsewhere more often have chosen to study in neighboring states. In contrast to the influx of students from states such as Minnesota, California, and Illinois, first-year students from Nebraska have continued to enroll in colleges and universities in Iowa, South Dakota, Kansas, Missouri, and Colorado at a relatively consistent pace (Chart 8). A smaller share of Nebraskans have pursued higher education in states further from home.

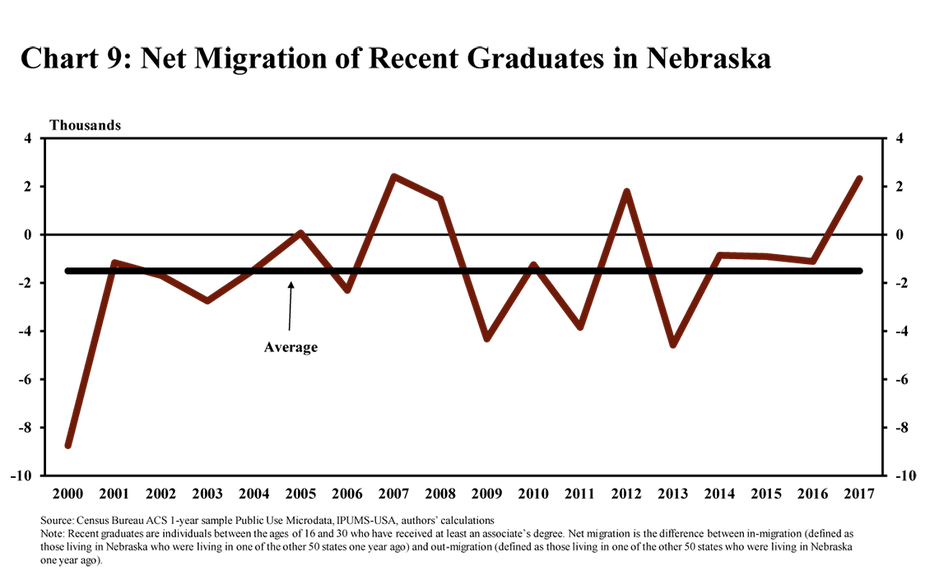

Although more first-year students have chosen to move to Nebraska for higher education than Nebraskans who have chosen to study elsewhere, many students appear to leave the state soon after graduating. Since at least 2000, a larger number of individuals who have received a degree (associate’s degree or higher), but are still under the age of 30, have left the state than those who have entered (Chart 9). The net migration of this age group has averaged about -1,500 since 2000, indicating a larger number of relatively highly educated individuals have left the state than have entered. Notably, however, more recent graduates relocated to Nebraska in 2017 (the latest data available) than left the state.

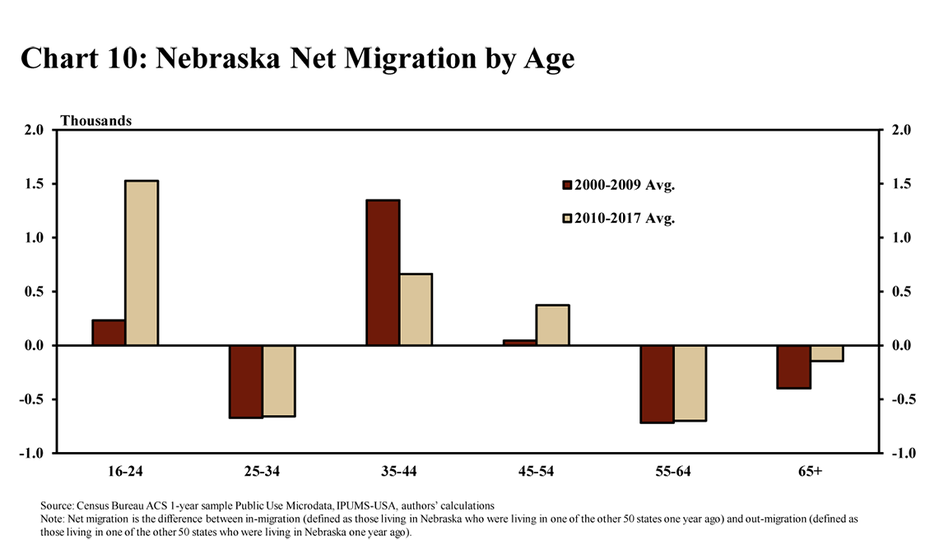

More positively, older, mid-career individuals have relocated to the state in higher numbers than those leaving. Although individuals between the ages of 25 and 34 have continued to move away, net migration of individuals between the ages of 35 and 54 has remained positive (Chart 10). These data suggest, as one scenario, that there are students who move to Nebraska for higher education, leave shortly after graduating, but return to Nebraska for employment later in life.

Attracting a Workforce to Nebraska

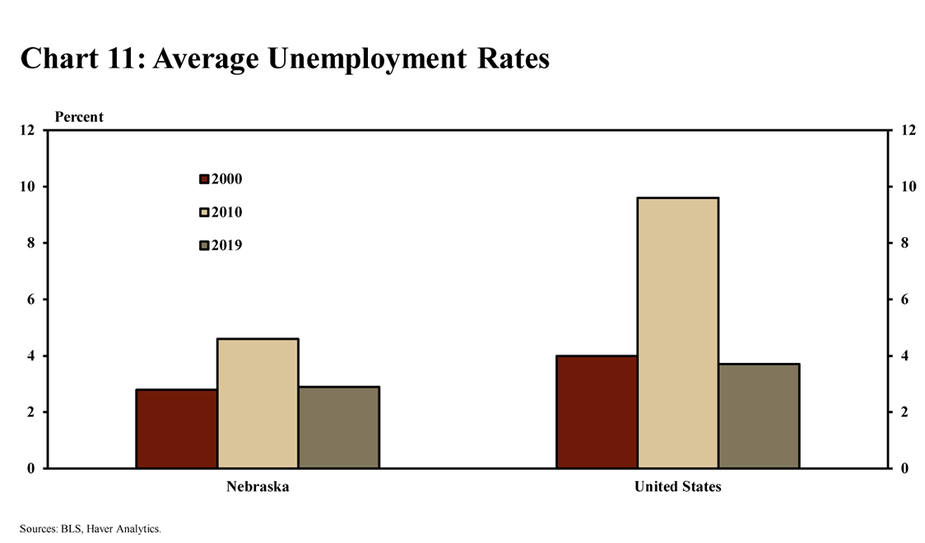

The opportunity to find employment in Nebraska likely has been an important contributor in attracting both households and students to the state. Although Nebraska’s unemployment rate has increased slightly to 3.1 percent in recent months, it has remained less than that of the nation (Chart 11). Following the Great Recession in 2007-2009, the rate of unemployment in the U.S., overall, peaked at 10.0 percent. In contrast, Nebraska’s unemployment rate peaked at just 4.9 percent, indicating that jobs generally have been available even during broader downturns in the national economy.

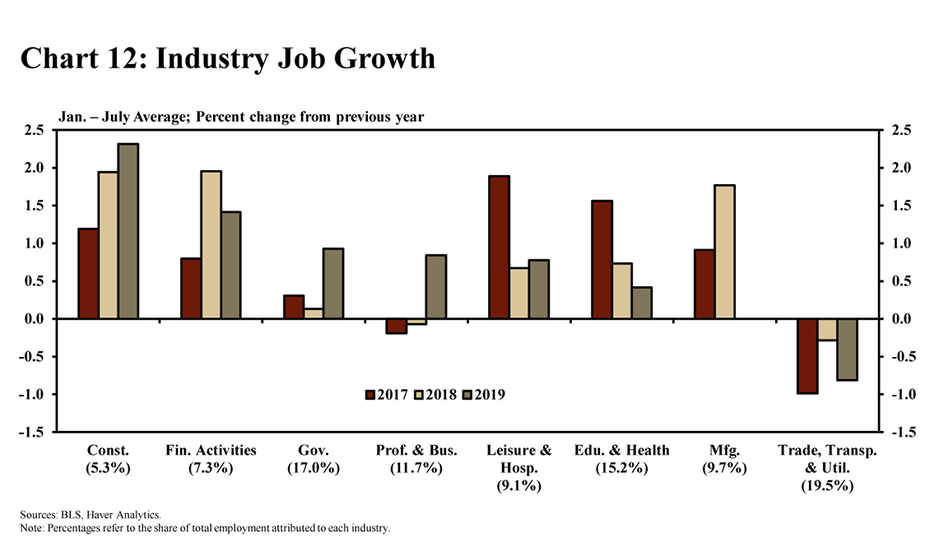

Employment in Nebraska has continued to increase at a modest pace in recent months and across many different industries. Over the past two years, hiring in the construction industry has continued to rise alongside a rebound in building activity throughout the region (Chart 12). Employment in almost all other industries has also continued to increase, including a significant rebound among firms categorized as professional and business organizations. An ongoing decline in retail sector employment, however, has continued to weigh on overall employment among trade, transportation, and utility firms.

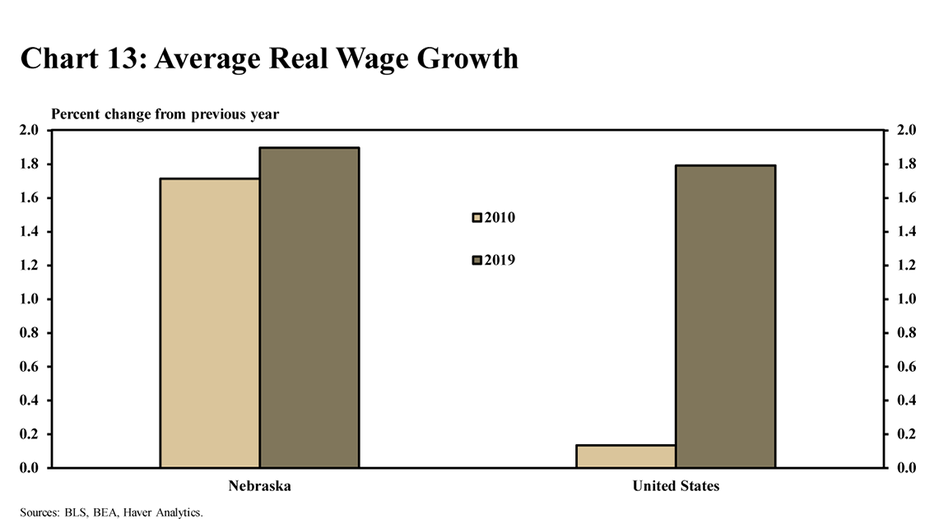

Wage gains in Nebraska have also continued to outpace the nation. In 2010, following the last U.S. recession, real average wage growth far exceeded that of the nation (Chart 13). Real wage growth has generally remained modest in both Nebraska and the U.S. in recent years, at slightly less than 2 percent. However, gains in Nebraska have maintained their edge above that of the U.S. alongside a low rate of unemployment and steady job gains in relatively high-paying industries.

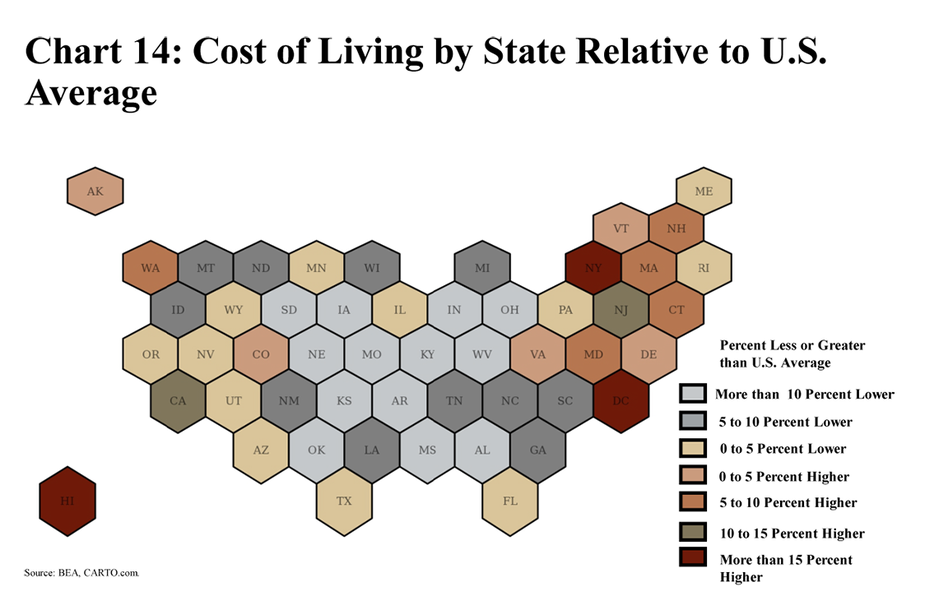

In addition to strong wage gains, Nebraska’s lower cost of living has likely been a factor that has continued to attract residents to the state. According to the Bureau of Economic Analysis, the average cost of living in Nebraska is about 20 percent less than that of the U.S. (Chart 14)_. More generally, the Midwest and Central Plains regions of the U.S. have tended to maintain a lower cost of living than states on either coast.

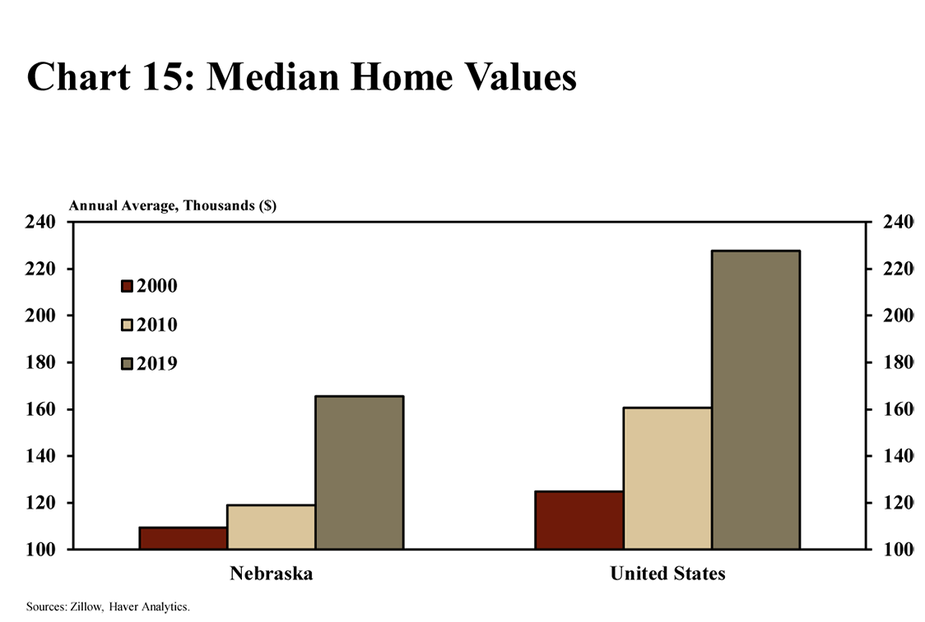

Moreover, despite ongoing home price appreciation, the price of homes in Nebraska has remained notably less than the nation. From 2000 to 2019, the median value of homes in Nebraska increased by about $56,000, or roughly 50 percent, according to data from Zillow (Chart 15). Since 2008, home prices in Nebraska have appreciated by 39 percent, the seventh highest in the country during that period, which includes the latest recession. Despite these notable increases, however, the median home value for the U.S. has exceeded that of Nebraska by more than $62,000 in 2019. For a prospective home buyer pursuing a 30-year mortgage at current interest rates, this amounts to an average of $300 per month less to buy a home in Nebraska than the average home in the U.S.

Conclusion

A recent increase in the number of individuals relocating to Nebraska, particularly younger individuals from more distant states, has contributed to the state’s population growth and available workforce. Institutions of higher education appear to be one source attracting new residents to the state, in addition to strong opportunities for employment and a low cost of living. Stronger retention of recent graduates could also help bolster the state’s available workforce as businesses have continued to face challenges filling positions in a labor market that has remained tight for several consecutive years.

Endnotes

-

1

The BEA publishes regional price parities by state that compare the buying power in each of the 50 states with one another. Price levels are relative to the overall national level.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City or the Federal Reserve System.