Nebraska’s economy has remained relatively strong, but recent growth has been slower. Measures of economic output and employment growth both slowed through 2017 alongside historically low levels of unemployment. Tightening labor markets likely have contributed to some of the recent slowdown as wage gains in Nebraska also have continued to accelerate. Though unemployment has remained low across the state, economic activity in rural areas has continued to weaken alongside persistently low agricultural commodity prices.

Economic Conditions

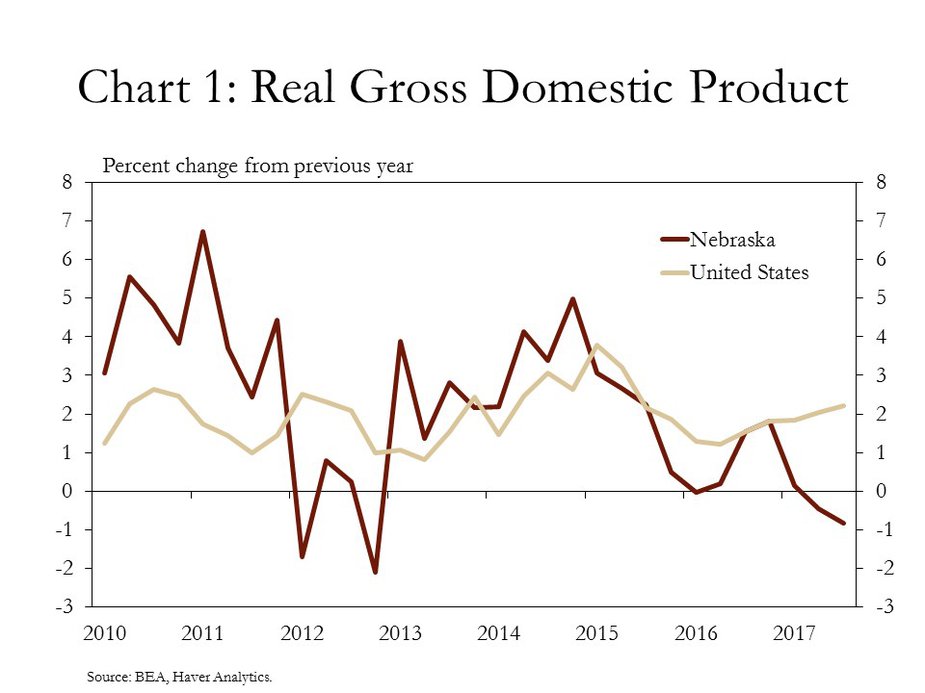

Economic growth in Nebraska slowed in 2017. While growth at the national level picked up, real gross domestic product (GDP) in the second and third quarters declined in Nebraska (Chart 1). The decrease in each quarter was the largest since 2012 when a severe drought across the state cut agricultural production and limited economic output. Agricultural commodity prices, however, which fell from 2013 to 2014, have remained relatively low since then. In recent years, including 2017, the low price environment for agricultural commodities has limited the potential for growth in the farm sector in addition to industries connected to agriculture.

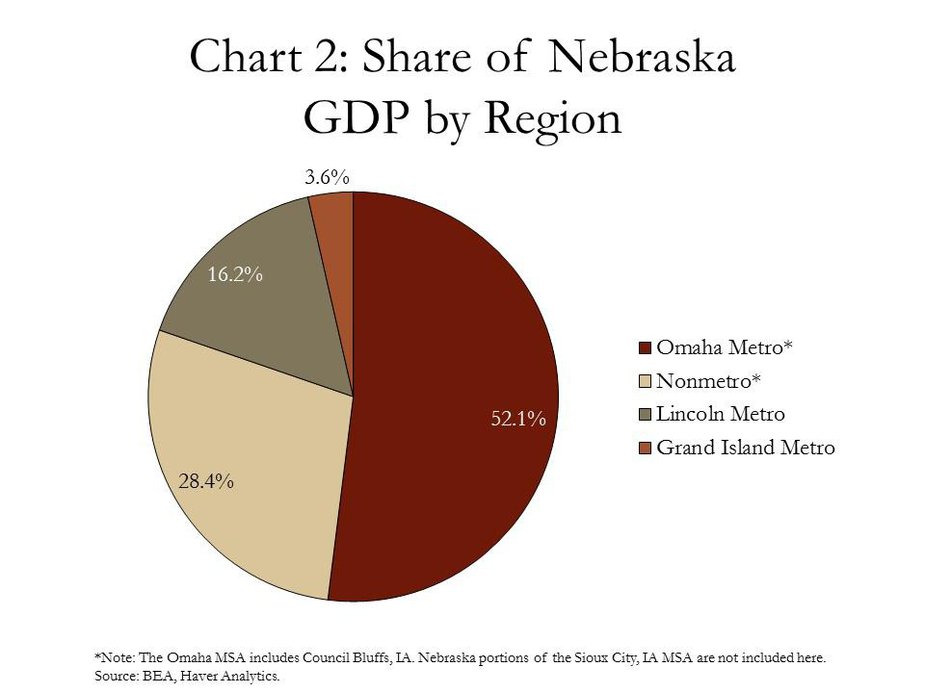

Unlike the country as a whole, rural Nebraska accounts for a relatively large share of the state’s economy. Although Omaha and Lincoln account for about two-thirds of the state’s economic activity, nonmetro regions in Nebraska accounted for nearly 30 percent of GDP in 2016 (Chart 2). Nationwide, nonmetro areas only account for about 10 percent of total economic output. Compared to the nation, then, economic growth in Nebraska is significantly more reliant on the economic health of its rural areas.

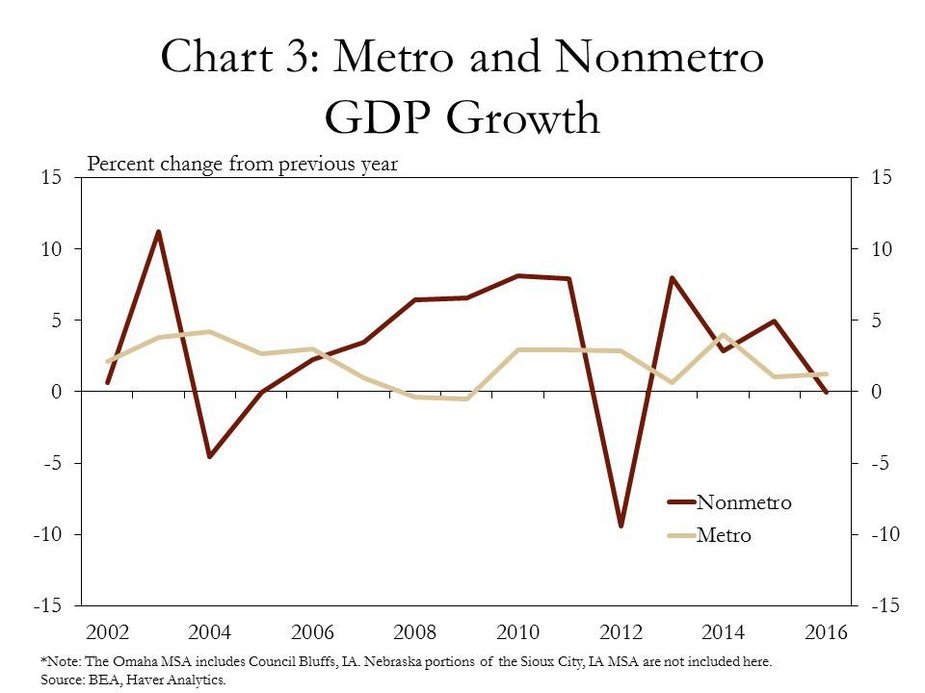

Economic growth in Nebraska’s rural areas has slowed recently, even as growth in metro areas has remained relatively stable. Since the Great Recession in 2007-09, economic growth in metro areas of Nebraska has averaged 2.2 percent with relatively little variation (Chart 3). Despite the recession, real GDP growth in the state’s nonmetro regions exceeded 5 percent from 2007 through 2013, except for the drought-induced pullback in 2012. From 2015 to 2016, however, growth slowed from nearly 5 percent to zero, even as growth in the state’s metro areas remained steady.

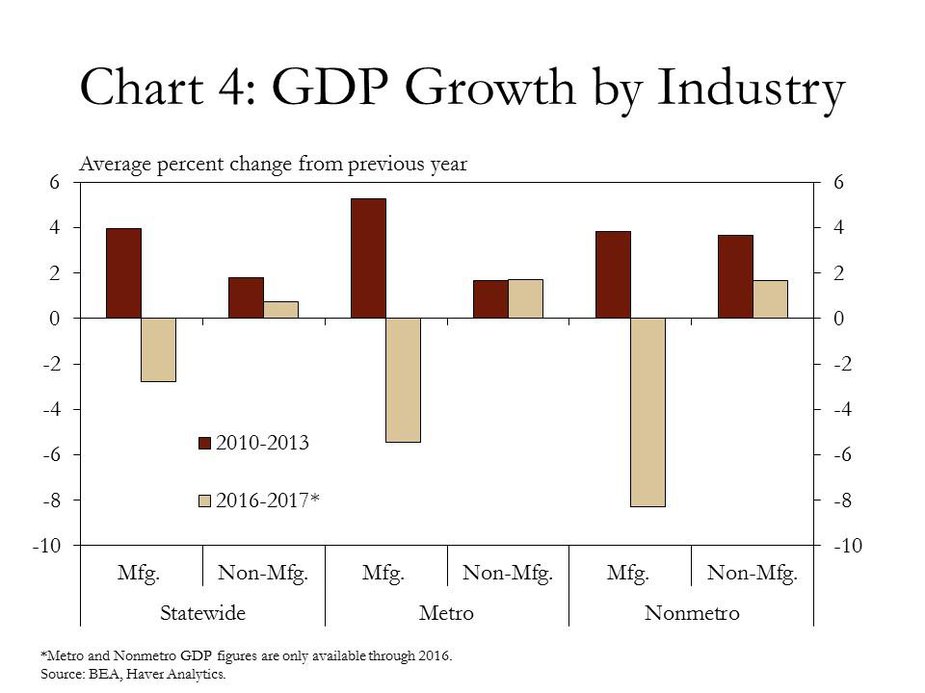

A downturn in manufacturing output has been a primary driver of the recent decline in economic growth, particularly in rural areas. From 2010 to 2013, alongside a strong agricultural economy, manufacturing contributed significantly to real GDP growth throughout the state (Chart 4). The last two years, however, GDP growth from manufacturing activity has fallen by an annual average of nearly 3 percent. The downturn has been especially pronounced in rural Nebraska. The rate of manufacturing GDP growth in nonmetro Nebraska declined about 8 percent in 2016, significantly lower than the rates of growth earlier this decade. A notable portion of manufacturing in Nebraska’s rural areas is connected to agriculture, and a persistently weak farm economy has continued to weigh on economic activity in those areas.

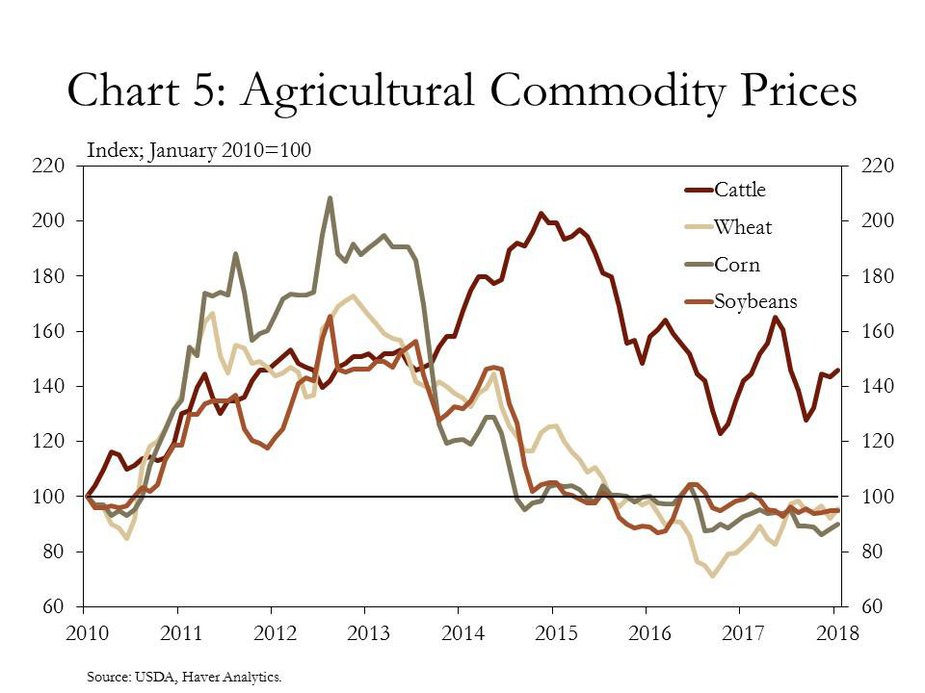

Agricultural commodity prices generally remained low throughout 2017. Although cattle prices rebounded modestly in 2017 before pulling back at year’s end, crop prices have remained flat for multiple consecutive years (Chart 5). At the end of 2017, the average price of corn was less than half its recent peak and about 12 percent less than 2010. Strong production in recent years has partially offset the effect of low commodity prices on farm income in some parts of the state. However, reduced farm income has weighed on industries connected to agriculture as farmers have continued to look for opportunities to cut spending.

Labor Markets

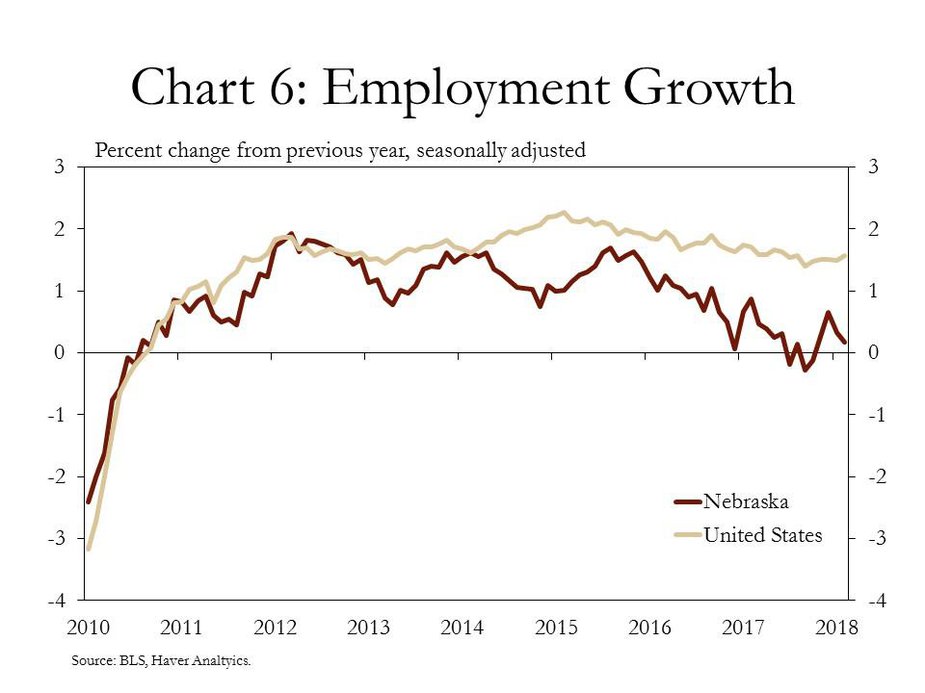

Similar to economic output, employment growth in Nebraska also slowed in 2017. The rate of statewide job growth fell throughout the year, including several months of job losses (Chart 6). While employment growth has rebounded modestly the past several months, job growth since 2015 has slowed steadily. Some of the slowdown in job growth, however, likely has been a result of tightening labor markets. With an unemployment rate of just 2.8 percent, employers have commented that the limited labor pool has made filling positions increasingly more difficult.

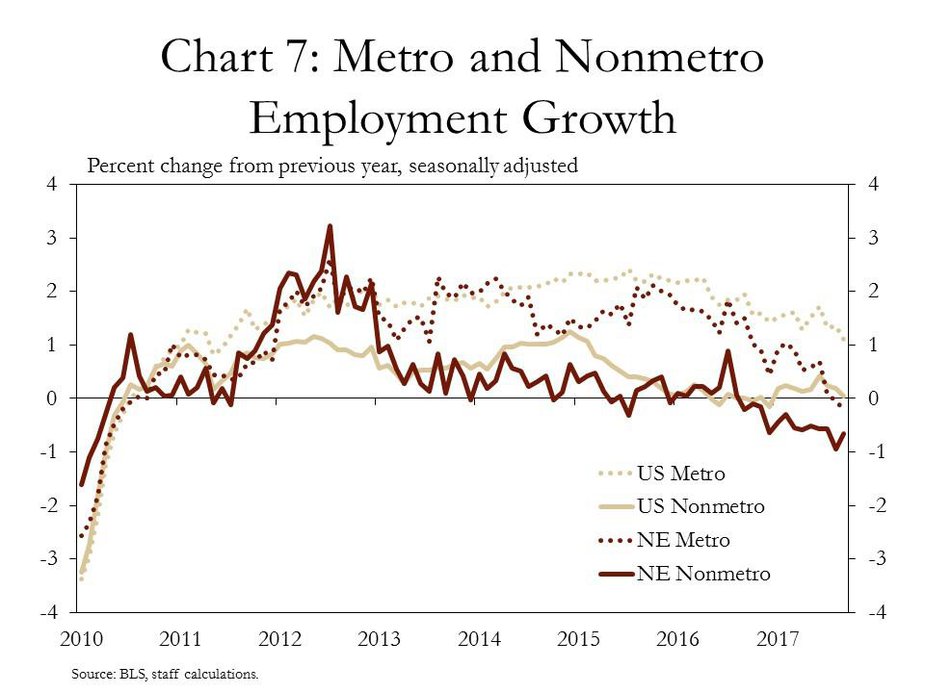

Though employment growth has slowed at the state level, job gains in rural areas in the last year have been weaker than in metro regions. In fact, employment has declined for more than 12 consecutive months in Nebraska’s nonmetro regions as labor availability has remained low and new job opportunities somewhat limited (Chart 7). Notably, however, employment growth also declined in August and September in the state’s metro areas.

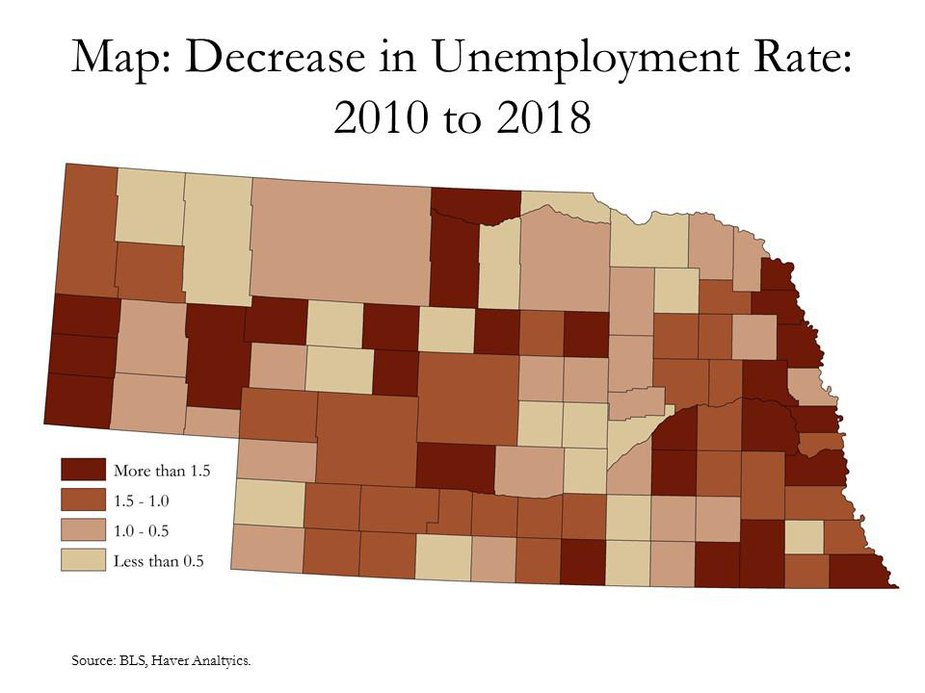

Labor markets remain tight across Nebraska, but most of the state’s recent job gains have been concentrated in the eastern portion of the state and along the I-80 corridor. Since 2010, local unemployment rates have fallen more than a full percentage point in most counties in the eastern third of the state (Map). And although unemployment rates in counties further west were not particularly high even in 2010, fewer jobs have been added in those counties since then.

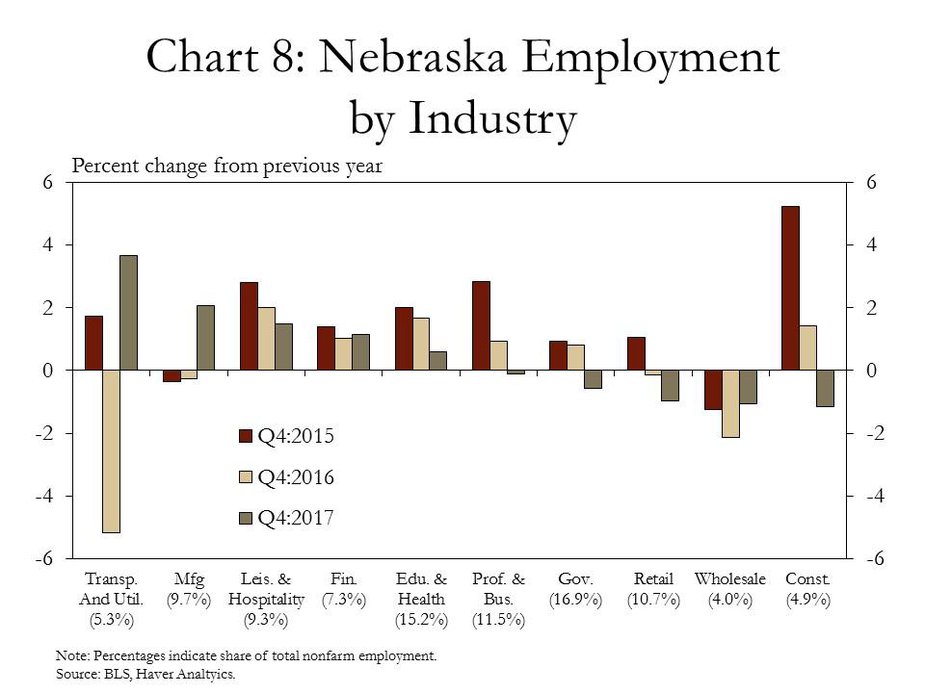

Job growth also has slowed across numerous industries in recent months. In the fourth quarter, employment fell in job categories that, collectively, account for about half of the state’s employment (Chart 8). In addition, job growth slowed among education and health service firms, which had been growing at a relatively solid pace. Construction employment also fell in the fourth quarter, in stark contrast to the past two years. On a positive note, however, manufacturing employment rebounded in the fourth quarter, which could be an indication that some of the challenges in the sector in 2016 and 2017 have abated somewhat.

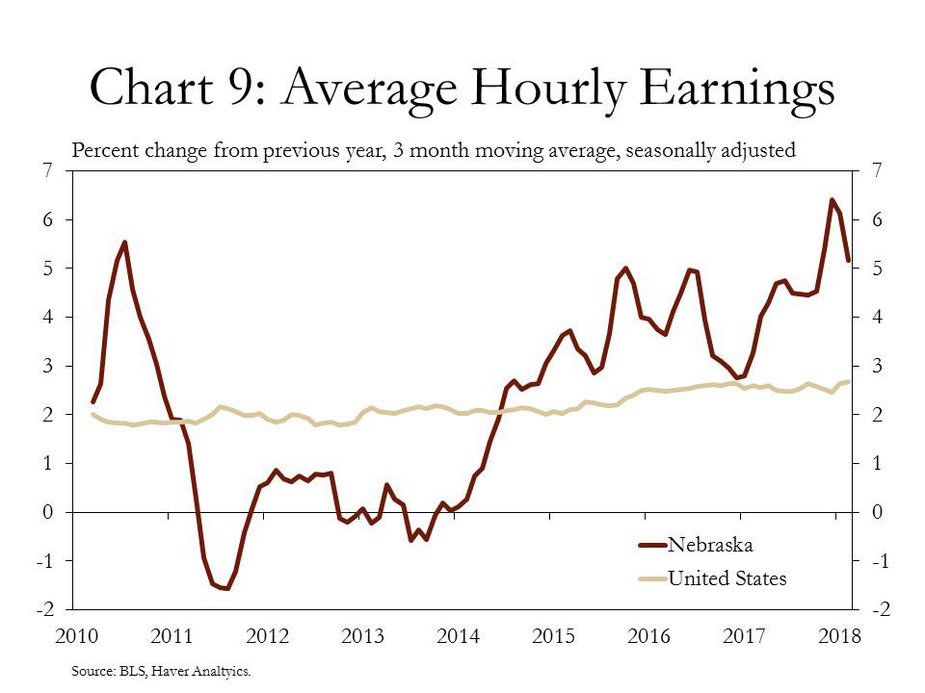

Sluggish job growth likely has been driven by tightening labor markets, which also have continued to drive wages in Nebraska higher. Wage growth has picked up steadily in Nebraska over the past two years, but accelerated more noticeably in the fourth quarter. Through the first three quarters of 2017, nominal wage growth averaged 4.1 percent, but accelerated to an average of 5.5 percent in the fourth quarter. Growth in 2018 continues to outpace that of the United States, with January and February both exceeding 5 percent (Chart 9).

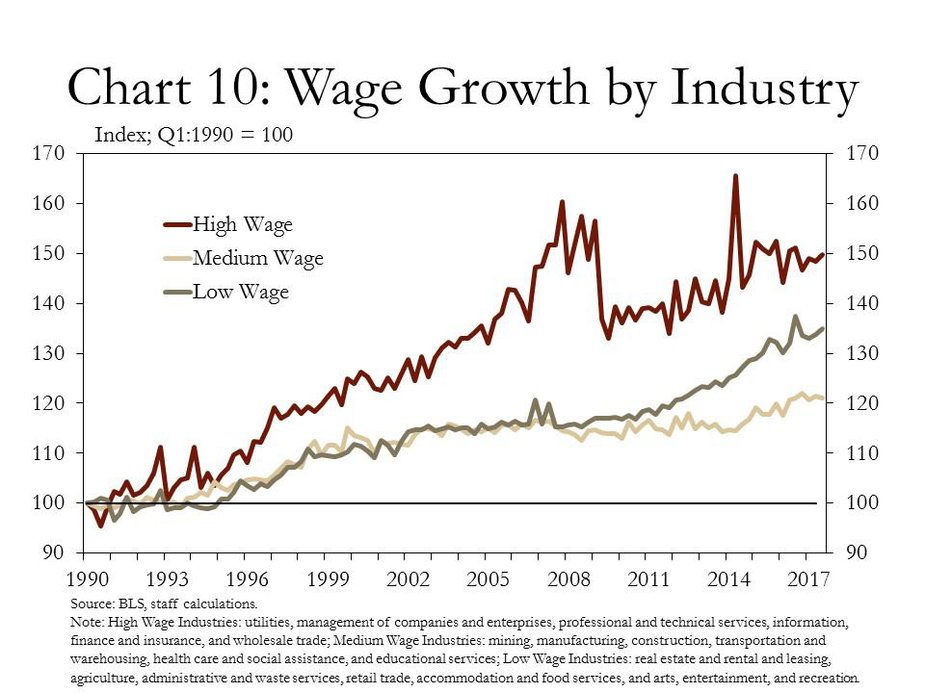

In contrast to previous years, recent gains in wages have been most pronounced in industries where wages are relatively low. Since 1990, wages have tended to rise most quickly in industries with high wages (Chart 10). Following the last recession, wage growth among medium-wage industries has remained relatively weak. From the beginning of 2015 through the third quarter of 2017, however, wages increased about 4.5 percent in low-wage industries, compared with 1.6 percent in medium-wage industries and a decrease of 1.5 percent in high-wage industries.

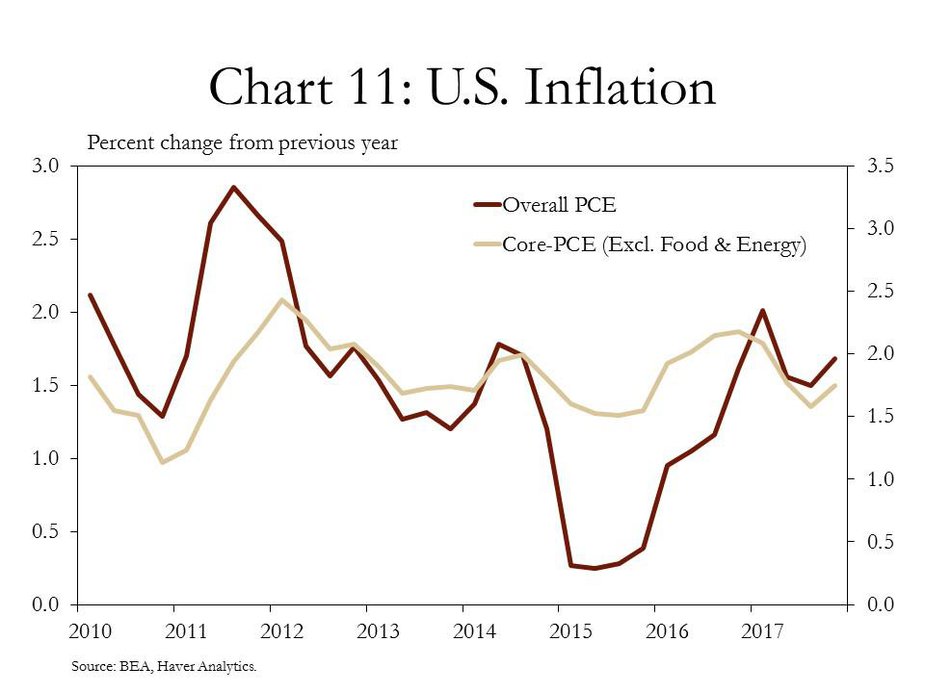

Wages in Nebraska have increased recently, even as inflation nationally has remained subdued. In the fourth quarter of 2017, overall inflation (referred to as “headline inflation”) was 1.7 percent (Chart 11). Core inflation, which excludes food and energy prices, was 1.5 percent, and has remained below 2 percent in recent years.

Conclusion

Low unemployment in Nebraska is a sign of a strong economy, but tightening labor markets and a weak agricultural economy may be limiting the potential for maintaining the growth of previous years. As the prices of most major agricultural commodities in Nebraska have remained low, industries connected to agriculture, such as manufacturing, have weakened over the past two years. In addition, a more limited supply of labor has continued to affect business growth prospects and firms have continued to raise wages at a slightly faster pace. As wage gains in the state have outpaced recent increases in the average price of goods and services, however, Nebraska households appear to be in a relatively strong financial position with solid job opportunities.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City or the Federal Reserve System.