The Federal Reserve System was created in late 1913. In addition to establishing 12 regional Reserve Banks, the Federal Reserve Act extended that regional presence by providing for Branch offices, saying that “each Federal Reserve Bank shall establish Branch Banks within the Federal Reserve District in which it is located.” The Denver Branch of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City opened Jan. 14, 1918. As the Branch approaches its centennial, this issue of the Rocky Mountain Economist examines how the economies of Colorado, New Mexico and Wyoming have been transformed over the past 100 years.

Population Growth over the Past 100 Years

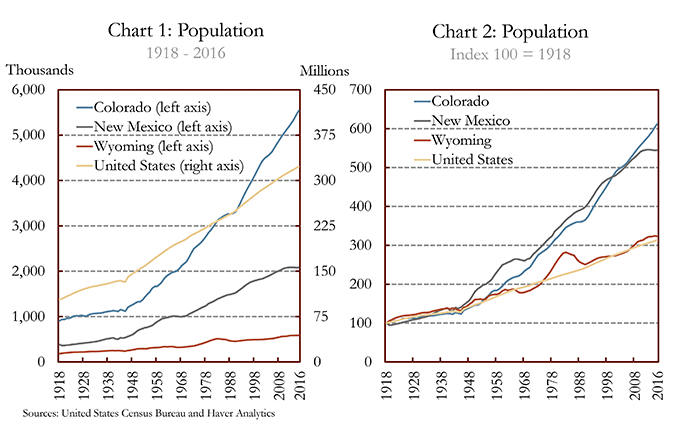

The Rocky Mountain States were still relatively new when the Denver Branch opened in 1918, with New Mexico entering statehood just six years prior. Among the three states, Colorado was the largest in 1918 with a population of 906,000, followed by New Mexico with 382,000, and Wyoming with 181,000 (Chart 1). Of course, populations have increased substantially since then, with growth in Colorado and New Mexico far outpacing the pace of growth at the national level (Chart 2).

Colorado’s population increased more than 500 percent between 1918 and 2016, an average annualized growth rate of 1.9 percent. New Mexico experienced similar rates of growth with average annual growth of 1.7 percent over the same period. Population growth in New Mexico outpaced Colorado in 31 of the 43 years from 1918 to 1960, but this trend has reversed in more recent years as Colorado‘s rate of population growth was higher than its southern neighbor in 42 of the 56 years from 1961 to 2016. In recent years, population growth has slowed dramatically in New Mexico due in part to some out-migration. From 2010 to 2016, annualized growth averaged 1.6 percent in Colorado compared to 0.1 percent in New Mexico.

Population growth rates for Wyoming and the United States have trended closely together over the last century, although Wyoming’s growth has been more volatile. The energy sector has played a substantial role in recent decades in Wyoming’s economy and population growth. In particular, Wyoming’s population soared during the energy boom in the early 1980s and then fell sharply as energy prices fell. Averaging over these fluctuations, annualized population growth rates over the last 100 years for the nation and Wyoming were both about 1.2 percent.

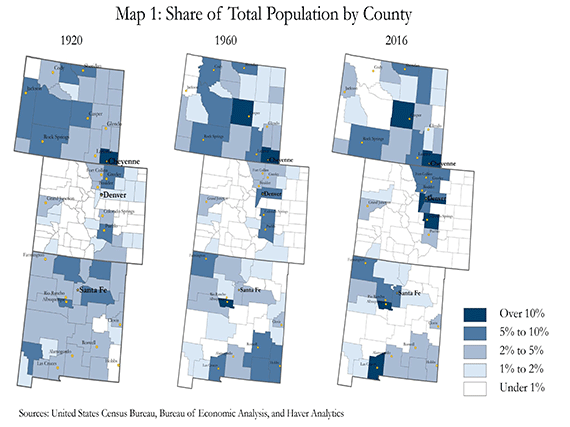

As population in the Rocky Mountain States grew, the distribution across the states shifted from nonmetropolitan areas to metropolitan areas. Map 1 shows the share of total state population by county in 1920, 1960 and 2016. In 1920, people were more dispersed geographically across the states compared to 2016, especially in New Mexico and Wyoming. Colorado’s population was relatively concentrated along the Front Range and Western Slope near Grand Junction in 1920, but there were also pockets in the south near Trinidad as well as the northeast that had higher concentrations than today. The counties with the largest populations for each state in 1920 were Denver County, CO at 256,000; Bernalillo County, NM (Albuquerque) at 30,000; and Laramie County, WY (Cheyenne) at 21,000.

Between 1920 and 1960, the population of the Rocky Mountain States increasingly moved from more rural areas into cities such as Casper, Cheyenne, Colorado’s Front Range cities, Grand Junction, Albuquerque and Las Cruces. This trend represents both regional and national effects, as gold mining prospects faded away and technological developments in agriculture led to fewer people needed to farm larger areas. This trend continued, and between 1960 and 2016 population shares increasingly moved into metropolitan areas. By 2016, the largest counties in each state remained the same as in 1920, but the share of the state population had increased from 13 to 27 percent in Denver County; from 8 to 33 percent in Bernalillo County; and from 11 to 17 percent in Laramie County.i

Employment Trends over the Past Century

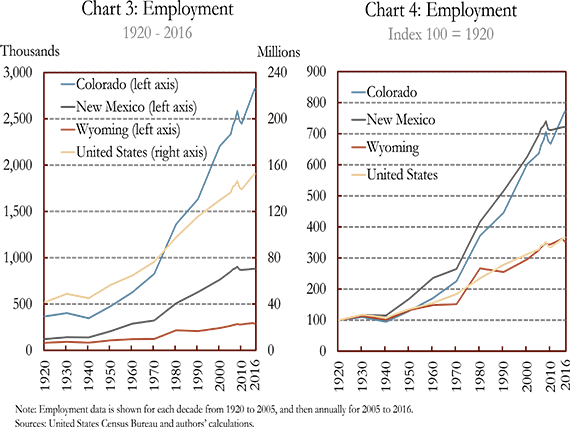

Similar to population, the level of employment over the last century in the Rocky Mountain States has steadily increased (Chart 3). However, employment gains have exceeded population gains over the past 100 years as labor force participation rates have increased for women.

Indexing the 1920 employment to equal 100 makes it easier to see that employment growth rates in Colorado and New Mexico have been similar over the past century, whereas Wyoming employment growth has trended more closely with that of the United States (Chart 4). Specifically, from 1920 to 2016, employment in Colorado and New Mexico grew at average annualized rates of 2.2 and 2.1 percent, respectively, while employment in Wyoming and the United States expanded at average annualized rates of 1.3 and 1.4 percent, respectively. Similar to population trends, growth in Wyoming’s relatively small employment base was more volatile than that of the United States due in large part to its heavy reliance on the energy sector.

The decade with the fastest employment growth was the 1970s, when annualized growth rates were 2.5 percent at the national level and between 4 and 6 percent in the Rocky Mountain States. This was primarily due to a surge of women entering the workforce; the rate of employment growth for women in the United States was twice as fast as that for men in the 1970s. As a result, the share of women in the workforce increased from 37.7 percent in 1970 to 42.4 percent in 1980.

Another notable period was the Great Depression during the 1930s, when all of the Rocky Mountain States and the nation experienced a decline in employment. The recent Great Recession of 2007-09 also caused significant job losses totaling about 5 percent for the Rocky Mountain States and the United States, as evident by the steep drops in Charts 3 and 4. As of October 2017, Colorado’s employment was well above its pre-recession peak from 2008 by 12.5 percent, more than double U.S. growth in the same period of 6.2 percent. New Mexico is very close to surpassing its pre-recession peak as it is only 0.7 percent below its 2008 peak. Wyoming, on the other hand, has experienced falling employment over the last three years due to the recent downturn in the energy sector and is now 8.1 percent below its pre-recession peak from 2008.

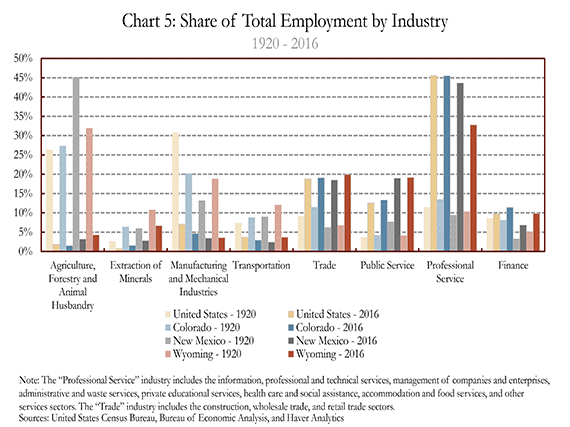

In addition to the growth in employment levels, there has been a considerable shift over the past century in the industry mix of employed workers (Chart 5). Technological advancements and changes in consumer preferences over the last 100 years have shifted resources, including labor, into different industries across the economy. New industries, such as those pertaining to information technology, have formed over time while some industries have been phased out or employ fewer workers.

There is a stark contrast between the largest industries in 1920, shown by the lighter-shaded bars, to the largest industries in 2016, shown by the darker-shaded bars. In particular, workers have shifted from agriculture, manufacturing and related industries toward more service-oriented industries. Advancements in technology have had a huge impact on the agriculture sector as a smaller share of the total workforce is needed to produce a greater amount of output. Overall, the share of the workforce employed in the agriculture sector has fallen from more than 25 percent in 1920 to less than 5 percent today. As technology advanced and the national population base increasingly moved west, the economies of the Rocky Mountain States were able to diversify.

The Rocky Mountain States have a rich mining history; the industry attracted many individuals to the region in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The high concentration of minerals and agricultural products were heavily relied upon by local manufacturing firms, which depended on raw materials for their inputs. However, similar to the agriculture industry, technological development has also occurred in the manufacturing sector across the United States. Specifically, improvements in technology have led to productivity gains in manufacturing, meaning fewer workers are needed to produce a given amount of product. The expansion of international trade has also led to increased competition and a rise in off-shore production of some manufactured goods. These forces, along with increased demand for service-oriented industries, have led to a decline in the share of manufacturing employment in the Rocky Mountain States from more than 13 percent in 1920 to fewer than 5 percent in 2016.

While the share of workers in the agriculture, mining and manufacturing sectors has declined over the past century, the share of workers in services sectors has increased significantly. In particular, employment in the professional service industry has grown from about 10 percent of total employment in 1920 to about 45 percent in 2016 for Colorado, New Mexico and the nation, and 33 percent in Wyoming. The increasingly heavy reliance upon service-oriented sectors over the last 100 years is not unique to the United States, but is a trend that has occurred in many of the world’s advanced economies. Efficiency gains in the production of manufacturing and agriculture have accommodated a shift in labor resources toward new service-oriented industries.ii The professional service industry includes a wide variety of sectors such as private educational services, health care, leisure and hospitality, information, and other professional and technical services such as legal services, advertising, engineering and accounting. The health-care sector is particularly noteworthy, as its share of total employment over the last 100 years has increased from less than 2 percent of total employment in 1920 to around 10 percent in 2016 in the Rocky Mountain States and the nation.

Per Capita Income Growth since 1929

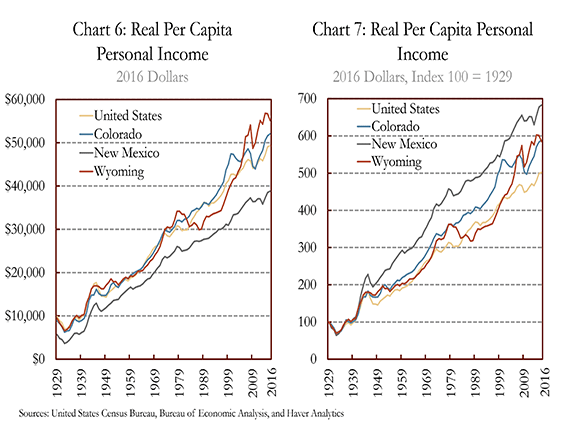

As the economies of the Rocky Mountain States have advanced and productivity has risen, so too has the income of its population. Chart 6 shows the evolution of real per capita income in the Rocky Mountain States and the nation from 1929, the first year this data is available, to 2016. Since 1929, per capita income has increased significantly, even after adjusting for inflation, suggesting that standards of living during that time have improved significantly on average.

In 1929, real per capita income was close to $10,000 in Colorado, Wyoming and the United States and slightly below $6,000 in New Mexico. Income growth during the following 10 years was fairly static, as the Great Depression pulled down incomes across the nation. Real per capita income increased sharply during World War II as more women entered the workforce, and then decreased slightly after the war ended. Key regional industries can also have a big impact on income patterns. For example, the energy crisis of the 1980s had a large negative impact on per capita income in Wyoming, while the build-up in the technology sector in Colorado in the 1990s had first a positive and then a negative effect on per capita income.

In more recent years, the Great Recession led to a decline in real per capita income, with Colorado and Wyoming experiencing declines of about 10 percent and the United States and New Mexico experiencing declines closer to 4 percent. Since then, all geographic areas have surpassed their pre-recession peaks for real per capita personal income, although Wyoming’s per capita income has fallen since 2014 when energy prices began to fall sharply. Over the entire period from 1929 to 2016, New Mexico has realized the fastest pace of per capita income growth in the region, but the level of per capita income in New Mexico remains below national levels.

Conclusion

The economies of the Rocky Mountain States have undergone significant change over the last 100 years. Employment and population growth has kept pace with national gains in Wyoming, while Colorado and New Mexico have witnessed much faster growth. Over the same period, the population has increasingly moved toward metropolitan areas, and employment has shifted away from agriculture and manufacturing into areas such as trade and professional service. Finally, real per capita personal income growth has increased significantly in the Rocky Mountain States, improving the standard of living across the region.

End notes

i. It is worth noting that the combined population share of the Denver-Aurora-Lakewood Metropolitan Statistical Area of Adams, Arapahoe, Broomfield, Clear Creek, Denver, Douglas, Elbert, Gilpin, Jefferson and Park counties increased from 33.6 percent in 1920 to 51.5 percent in 2016.

ii. Rowthorn, Robert, and Ramana Ramaswamy. Deindustrialization - Its Causes and Implications. International Monetary Fund, September 1997.