The energy sector is struggling. Oil prices have dropped sharply over the last two years, falling from more than $100 a barrel to less than $30 from June 2014 to January 2016. In addition, natural gas prices have fallen more than 80 percent since mid-2008, and coal production has declined by half in the same period. As the energy sector contracted, the economies of Colorado, New Mexico and Wyoming slowed to differing extents. This boom-bust cycle is not a new phenomenon for the energy sector or the Rocky Mountain States, with many residents remembering the sharp declines in the mid-1980s. This issue of the Rocky Mountain Economist examines the recent effects of low energy prices on the Rocky Mountain States and compares this downturn in the energy sector to past energy busts.i

The Importance of the Energy Sector to the Regional Economy

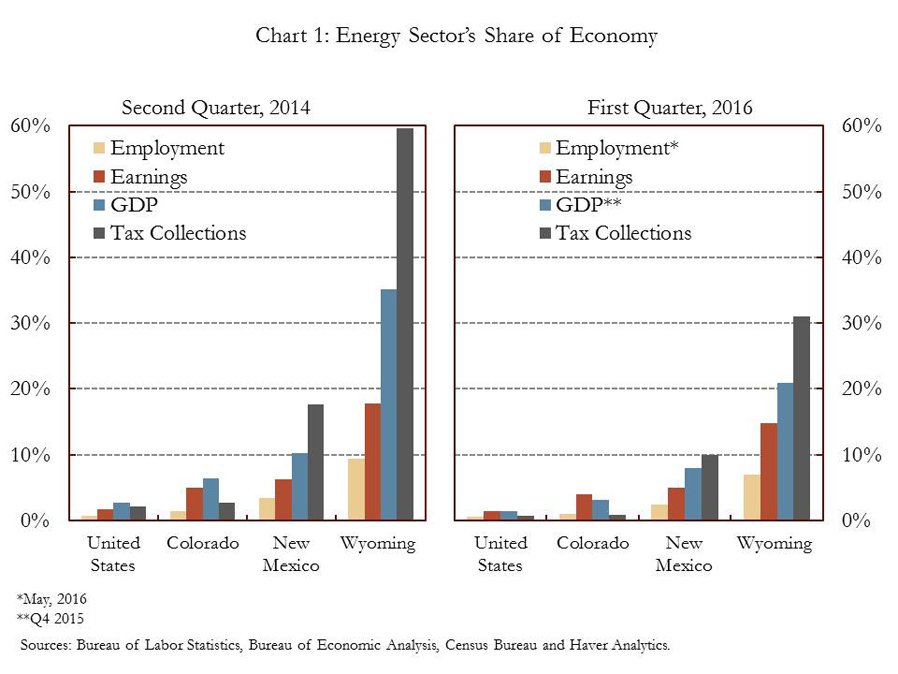

The energy sector is a key industry in Colorado, New Mexico and Wyoming, with each state’s share of economic activity attributed to the energy sector being larger than the national average. Chart 1 shows the energy sector’s share of total employment, earnings, gross domestic product (GDP), and tax collections in the second quarter of 2014, just before the recent decline in oil prices began, and its share in the first quarter of 2016. Among the Rocky Mountain States, Wyoming is the most reliant on the energy sector. In the second quarter of 2014, almost 10 percent of Wyoming employment was tied directly to the energy sector. In addition, the energy sector accounted for 18 percent of personal earnings, 35 percent of GDP and almost 60 percent of tax revenues in Wyoming. Although the energy sector represents a relatively smaller share of the economies of Colorado and New Mexico, the sector still made up more than 6 percent of GDP in Colorado and more than 10 percent in New Mexico in mid-2014.

As the energy sector has contracted, it now represents a smaller share of the economy. For example, energy’s share of Wyoming employment had fallen to less than 7 percent by May 2016, and its contribution to Wyoming tax revenues had dropped to 31 percent. Similarly, the energy sector’s share of GDP in Colorado and New Mexico had declined to 3.1 and 8.0 percent, respectively, by the fourth quarter of 2015.

The Effect of the Recent Energy Downturn on the Regional Economy

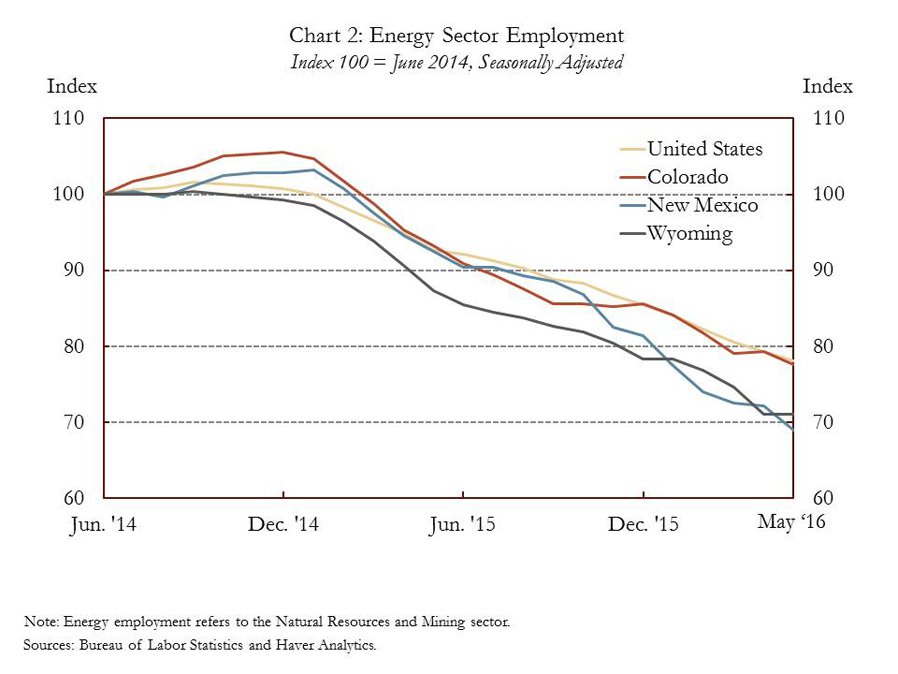

As energy prices fell sharply, activity in the energy sector contracted. The number of active drillings rigs has declined more than 70 percent nationally and in the Rocky Mountain States.ii Initially, oil production continued to rise even as prices fell, with productivity in the industry continuing to increase as the least-productive rigs were shut down. However, production started to drop in mid-2015 and is now down from peak levels by 4 percent in Colorado, 6 percent in Wyoming and 19 percent in New Mexico.iii As energy companies struggled, layoffs in the sector increased and employment decreased sharply. Energy employment peaked several months after oil prices started to decline, but since has decreased more than 25 percent in Colorado, New Mexico and Wyoming (Chart 2).

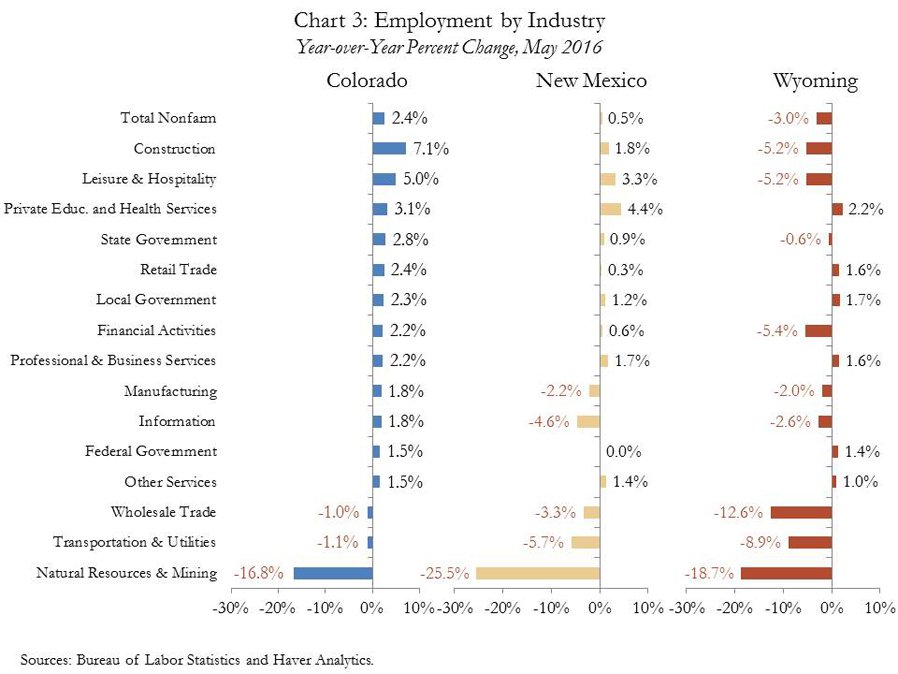

Although the effects of a low energy price environment are largest in the energy sector itself, there frequently are spillover effects on related industries or the economy as a whole. Employment in the transportation sector has declined over the past year in Colorado, New Mexico and Wyoming (Chart 3). The transportation sector is closely tied to the energy sector, providing many logistical services such as moving commodities by truck or train. In fact, coal shipments were about 39 percent of total tonnage moved by rail in 2014.iv Colorado, New Mexico and Wyoming also have experienced declines in wholesale trade employment, which may be tied to the energy sector. Many of the region’s manufacturing firms make goods directly for the energy sector, and therefore manufacturing employment in New Mexico and Wyoming has declined over the past year in part due to weakness in the energy sector. With almost one in 10 workers employed in the energy sector in mid-2014, Wyoming has seen the largest spillover effects from the recent downturn in energy. In addition to employment declines in energy, transportation, manufacturing and wholesale trade over the past year, employment has fallen in construction, financial services, information, leisure and state government. In contrast, most industries continued to expand in Colorado despite the slowdown in the energy sector.

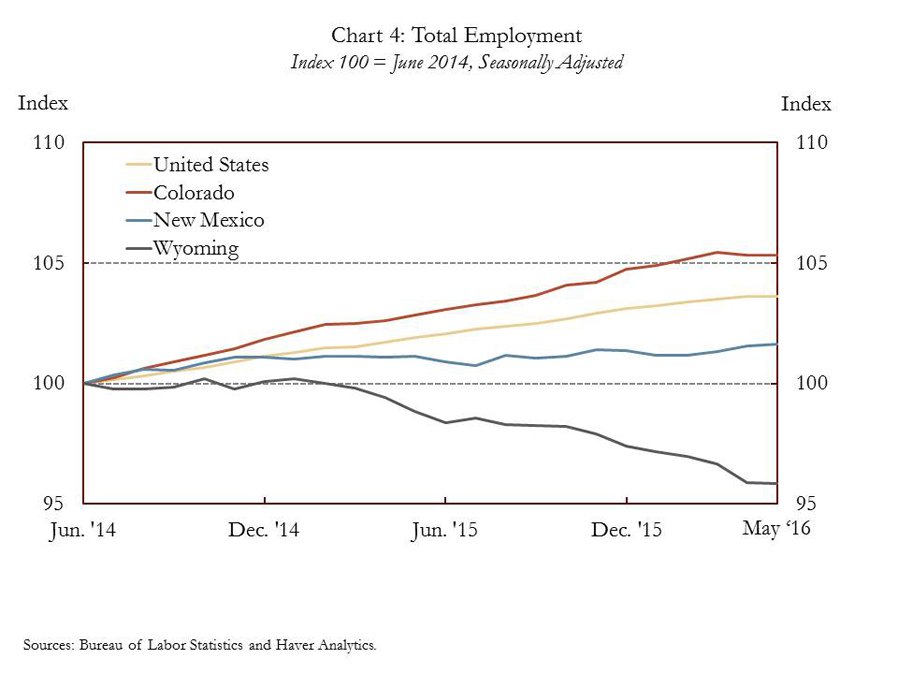

The effect on total employment will depend both on the concentration of the energy sector in the state and also the extent to which weakness in the energy sector spreads to other sectors of the economy. Total employment in Wyoming has dropped more than 4 percent due to the large presence of energy employment in the state and the large spillover effects to other industries (Chart 4). In New Mexico, total employment has increased slightly despite layoffs in the energy sector. Employment gains in healthcare, leisure and professional and business services have helped to offset employment losses in energy, transportation, manufacturing and wholesale trade in New Mexico. Unlike New Mexico and Wyoming, employment in Colorado has expanded at a solid pace since June 2014. The diversification of employment in the state and the strength of many other sectors in Colorado have helped to mitigate the downside effects from the energy sector. However, the pace of employment growth in Colorado has slowed over the past year due in part to energy sector layoffs.

As employment in the energy sector has declined, so have total personal earnings attributed to the sector. As of the first quarter of 2016, energy sector earnings had fallen about 14 percent nationally and in Colorado and more than 18 percent in New Mexico and Wyoming from their peak levels in mid-2014.v This decline in total earnings in the energy sector has been driven primarily by the decline in energy employment.

The decline in energy prices, production, employment and earnings also have affected state tax revenues. In particular, severance tax revenues are significantly lower than their mid-2014 levels as these taxes typically are based on both the price and extracted volume of natural resources. As the price of these commodities falls, so does severance tax revenue, even if the volume of extraction remains level. As of the first quarter of 2016, severance tax collections were down more than 70 percent nationally and in Colorado and Wyoming compared to peak levels, with New Mexico severance tax revenues down 55 percent.vi Income and sales tax revenues can also be affected by weakness in the energy sector, particularly if the sector makes up a large share of the state economy.

How Does the Recent Energy Downturn Compare to Historical Downturns?

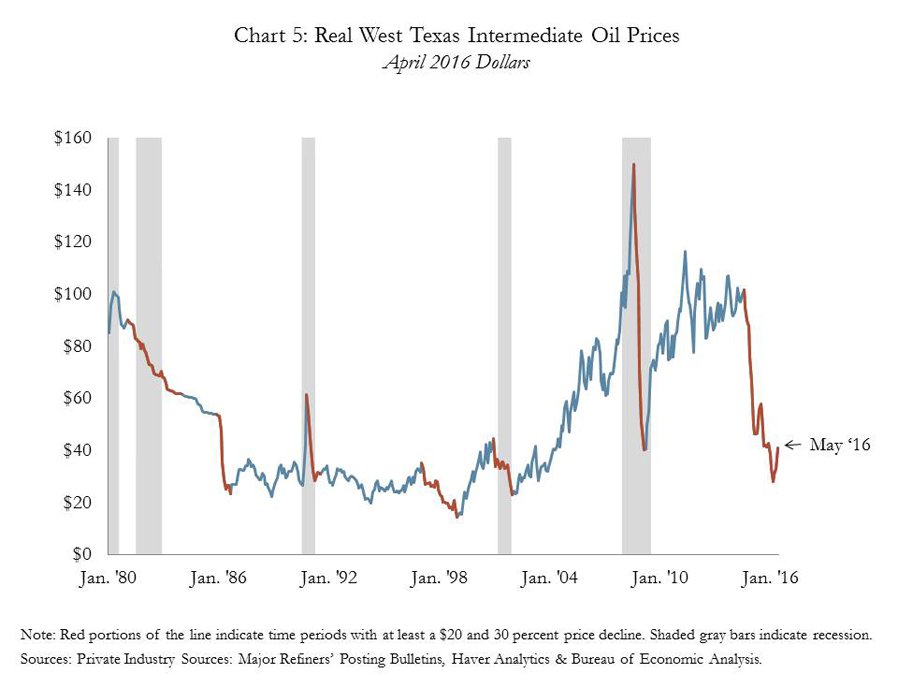

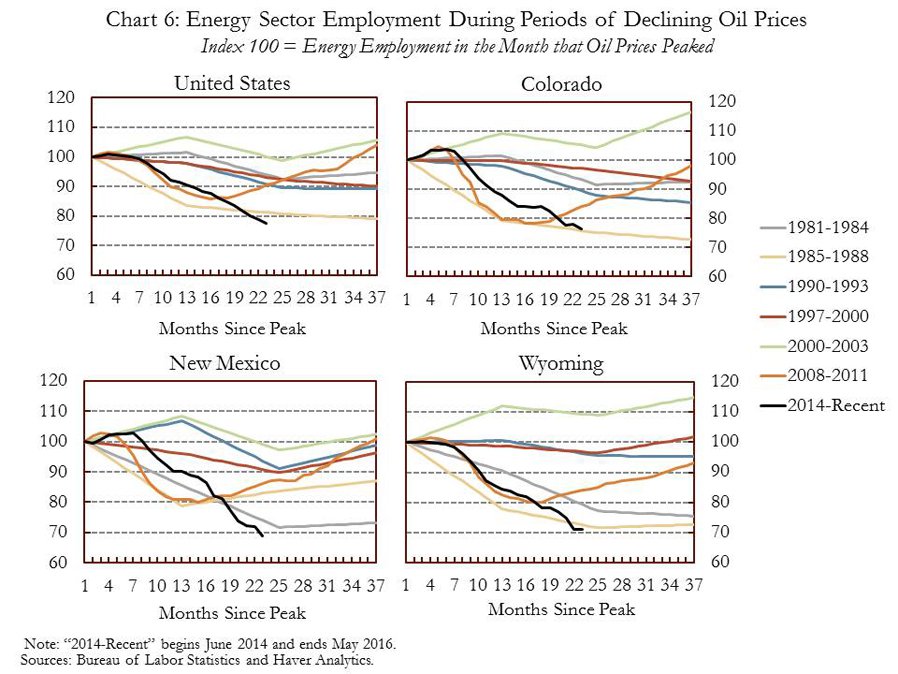

There have been other significant energy price shocks over the last 40 years that are similar to the current downturn, including six periods when oil prices declined more than 30 percent (Chart 5). Aside from the large energy price decline during the 2007 recession, which caused large negative economic effects due to the severity of the national recession, the oil price decline in the mid-1980s had the largest negative effect on the regional economy. Chart 6 shows employment growth for the energy sector during the seven periods when oil prices declined more than 30 percent.vii

In the most recent episode, oil prices peaked in June 2014. Initially, employment declines in the energy sector were less severe than the declines during the oil busts in the 1980s and the 2007 recession. However, after nearly two years of the current downturn, energy sector employment has declined more than in any previous oil price downturn. Between June 2014 and May 2016, energy employment has dropped more than 20 percent nationally and in Colorado and about 30 percent in New Mexico and Wyoming.

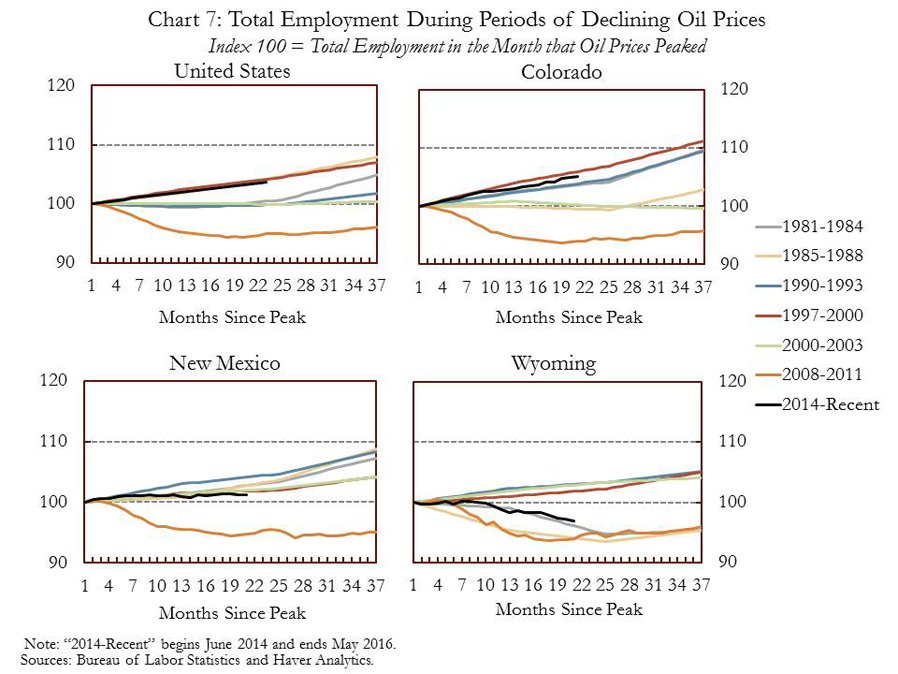

Total employment, however, has performed better by comparison (Chart 7). Nationally and in Colorado, total employment has continued to increase at a solid pace and is outperforming most of the previous oil bust periods. In New Mexico, total employment has fared worse than most previous energy downturns, but remains higher than employment levels in June 2014. And although total employment has declined about 3 percent in Wyoming since mid-2014, its performance is better than in the 1980s energy downturns and the 2007 recession.

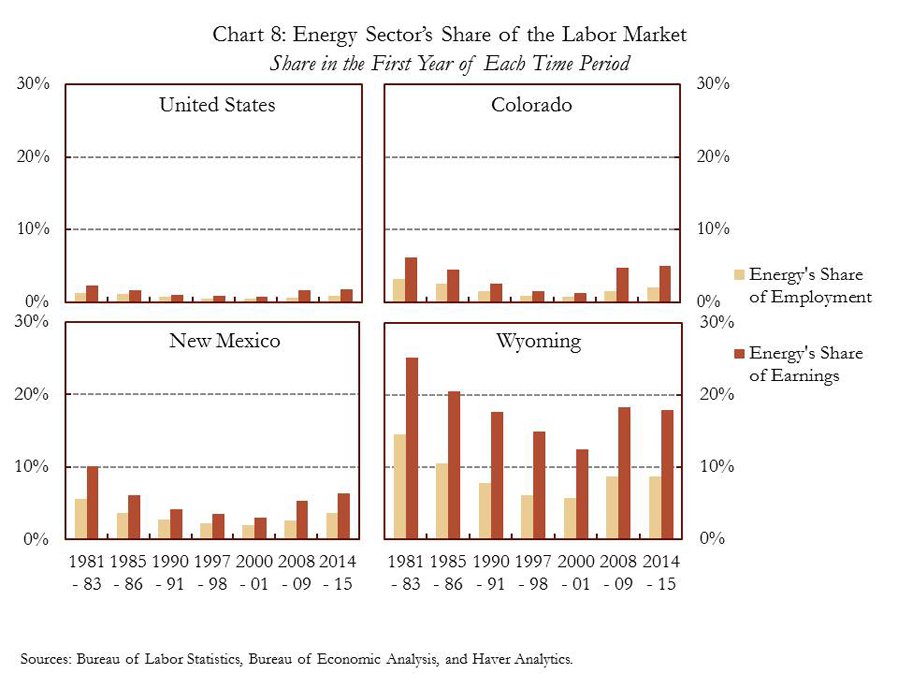

Heading into the current energy sector downturn, the sector’s share of employment and earnings was slightly lower than its share in the early 1980s (Chart 8). For example, energy employment made up 2 percent of Colorado employment in 2014 compared to 3.1 percent in 1981. Similarly, energy’s share of employment fell from 5.5 percent to 3.6 percent in New Mexico and from 14.5 percent to 8.7 percent in Wyoming. The slightly lower reliance on the energy sector in 2014 compared to 1981 may help explain why total employment performed better in Colorado and Wyoming during this downturn despite sharp losses in energy sector employment.

Conclusion

The recent decline in oil prices has led to a sharp pullback in the energy sector nationally and in the Rocky Mountain States. Not only has the energy sector itself experienced job losses, but related industries including transportation, wholesale trade and manufacturing also have experienced regional employment declines. Furthermore, weakness in the energy sector has led to lower earnings in the sector and reduced severance tax collections for state governments. The extent to which the adverse effects permeate the rest of the economy depends on the size of the energy sector relative to other sectors of the economy.

End notes

i The terms “energy,” “energy and mining” and “mining” all refer to the “Mining, Quarrying, and Oil and Gas Extraction” (NAICS code 21) sector unless otherwise specified. The “Mining, Quarrying, and Oil and Gas Extraction” sector consists of the following subcategories: “Oil and Gas Extraction,” “Mining” and “Support Activities for Mining.” Furthermore, in 1997, the United States introduced the NAICS to replace the SIC as the primary industry classification system. Prior to 1998, the SIC category “Mining” (SIC codes 10-14) is used for GDP, employment and personal earnings. The SIC category “Mining” consists of the following subcategories: “Metal Mining,” “Bituminous Coal and Lignite Mining,” “Oil and Gas Extraction” and “Mining and Quarrying of Nonmetallic Minerals, except Fuels”.

ii Baker-Hughes.

iii Energy Information Administration.

iv Association of American Railroads.

v Bureau of Economic Analysis and Haver Analytics.

vi United States Census Bureau.

vii Data for the 1980s is annual but is monthly for the more recent time periods. The index is set to 100 for either the year or the month where the peak real price of oil occurred.