COVID-19 presented a relatively unprecedented threat to public health and the economy. Public health authorities and government leaders responded with orders to substantially curtail transmission. Similarly, consumers reduced their activity in public spaces. This resulted in millions of people losing their jobs, practically overnight. The mass job loss disproportionately affected low-wage workers, people of color and women. They also were more likely to rent their homes. With fewer protections than homeowners, renters who lost their jobs quickly were faced with the prospect of losing their homes.

A landlord filing an eviction case – even if a court does not complete an eviction – can severely hinder someone’s ability to find safe and affordable housing in the future. A lack of stable housing may hinder someone’s ability to find and keep a job and affect their children’s ability to regularly attend school.[1] This presents a drag on the economy in normal times, and with the wave of evictions possible from the pandemic, the economic effects could be large.

The following is a summary of the External LinkEvictions and the Pandemic Economy in the Tenth District report, which covers who lost jobs in the pandemic, an estimated scale of the eviction crisis and a possible policy response.

COVID-19 pandemic forced millions out of work

More than 32 million people were unemployed at the peak of pandemic-related job losses. Women, people of color and low-wage workers were highly concentrated in industries that shed jobs. They also worked in industries that could not easily shift to working remotely. While relief checks and unemployment insurance helped, many low-wage workers fell behind on rent.

Housing already was unaffordable

In 2019, about 79% of renter households across the Tenth District who earned less than $35,000 a year were burdened by the cost of housing. The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development defines this as spending more than 30% of their income on rent and utilities. Housing already was hard to afford without facing a loss of work. Many low-wage workers have faced nearly a year and a half of income disruption.

Evictions continued throughout the pandemic

More people living in crowded conditions could lead to more spread of COVID-19. As such, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) implemented a nationwide External Linkeviction moratorium that expired July 31, 2021. Following the expiration of the nationwide moratorium, the CDC implemented a new order that only applies to areas with substantial rates of COVID-19 transmission and will expire Octo. 3, 2021. As of Aug. 4, about 85% of counties in the District were covered by the new moratorium. Counties are covered by the order if their transmission levels exceed 50 cases per 100,000 people or positive test rates are above 8%. Even with the eviction moratorium in place, evictions continued.

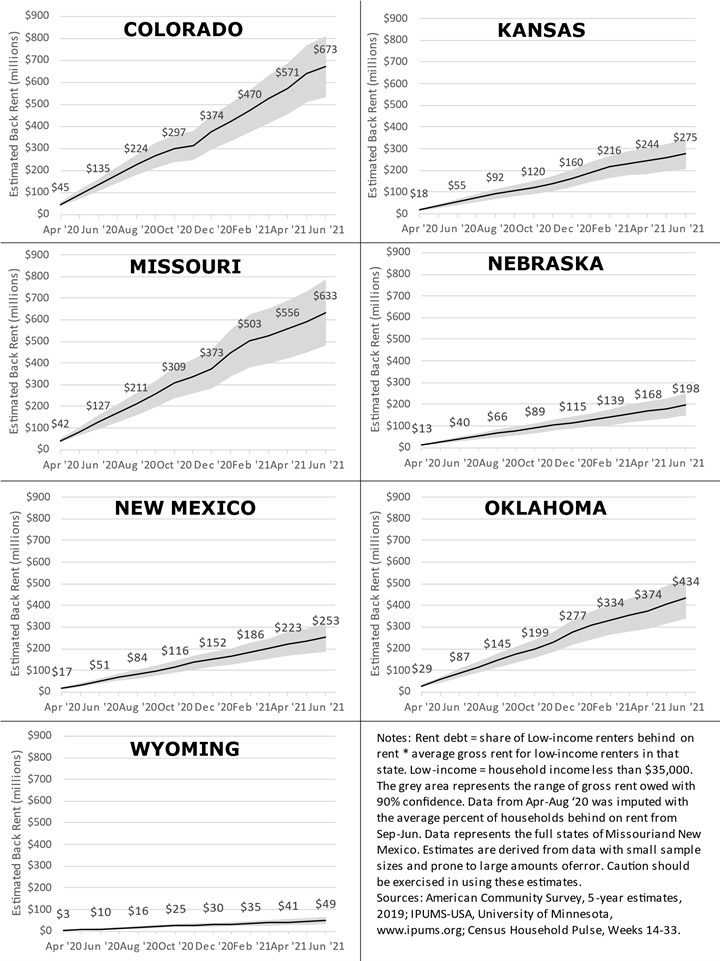

I estimate that between 160,000 and 260,000 low-income renter households in the Tenth District may be behind on about $2.5 billion in rent and utilities. The Tenth District received about $3.3 billion of the $45 billion Congress appropriated for rental assistance. However, limited staff capacity, difficult documentation requirements and issues with tenant and landlord responsiveness has made it difficult for tenants to receive timely assistance.[2] While Chart 1 shows that some states do not have as much rent debt as others, the figures are more representative of the population differences of the states. On average, for each month in the pandemic, around 16% of low-income renters in each state reported being behind on rent.

Chart 1: Estimated Cumulative Rent Debt for Low-income Renter Households

Policy responses available

Evictions were a problem long before the pandemic. The pandemic only highlighted how easy it was for evictions to occur. There are many options available for cities, counties, or states to explore if they choose to act.

In the short term, jurisdictions can ensure their rental assistance programs are operating at the highest possible efficiency. That includes information and outreach campaigns, streamlining the application and getting assistance directly to the tenant when landlords do not respond in a timely manner.

Cities, counties and states also may intervene in the eviction process:

- Eviction mediation programs allow both parties to negotiate before an eviction is filed.

- Eviction diversion programs are a multipronged effort to prevent evictions by helping tenants with robust rental assistance, legal support and mediation requirements.

- Tenant right to counsel provides tenants with free legal counsel to represent them in eviction cases. Legal counsel provides a tenant support in accessing available resources, learning their rights as a tenant and negotiating before being removed from their home.

Lastly, evictions largely are an effect of a lack of affordable housing and low wages. Very few places have enough units available at rents affordable for low-wage workers. Increasing the supply of affordable housing can help, but so can increasing wages. Many jurisdictions across the District have increased their minimum wage above the federal level, but wages often are inadequate when compared with the cost of housing. According to the American Community Survey, the average low-income renter in the Kansas City metro area was paying $780 a month for rent and utilities in 2019. A full-time worker earning $12 an hour, though, reasonably could afford $625 a month. An extra $1,800 a year is especially hard for a family that earns about $25,000 a year.

All of these policy options have a cost. But there also is a cost for inaction. People facing eviction have increased likelihoods of seeking services for homelessness and medical care.[3] They are more likely to interact with child welfare services and the criminal justice system.[4],[5] The University of Arizona has developed a “External LinkCost of Eviction Calculator” that estimates the cost to public services from evictions. This does not include the economic cost of employment and education impacts from housing instability or the cost to landlords for missed payments and cost of the eviction process. Evictions disproportionately occur in low-income neighborhoods and to women and people of color, exacerbating existing economic inequalities.[6] With housing instability connected to economic stability, it is important to consider the long-term economic costs and unequal effect of evictions.

The External Linkfull report contains more information on how the pandemic has led to a potential evictions crisis and what may be done to address it.

Endnotes

-

1

Desmond, M. (2016). Evicted: Poverty and Profit in the American City. Crown Publishers, New York.

-

2

For more information on what is leading to slow dispersal of rental assistance funds, see this report: https://nlihc.org/sites/default/files/HIP_NLIHC_Furman_2021_6-22_FINAL_v2.pdf

-

3

Collinson, R., and Reed, D. (2018). “The Effects of Evictions on Low-Income Households.” https://www.law.nyu.edu/sites/default/files/upload_documents/evictions-collinson_reed.pdf.

-

4

Bullinger, L.R., and Fong, K. (2021). “Evictions and Child Maltreatment Reports.” Housing Policy Debate, 31(3-5): 490-515.

-

5

Herring, C., Yarbrough, D., and Alatorre, L.M. (2020). “Pervasive Penalty: How the Criminalization of Poverty Perpetuates Homelessness.” Social Problems, 67: 131-149.

-

6

Hepburn, P., Louis, R., and Desmond, M. (2020). “Racial and Gender Disparities Among Evicted Americans.” Sociological Science, 7: 649-662.